Notable Internet disruptions observed in October were generally short-lived and due to power outages, cable cuts, and other acknowledged but unexplained network issues. However, the most significant disruption observed during the month occurred in Iraq, and was due to a government directed shutdown of Internet connectivity for over a week in response to violent protests. Total losses due to this shutdown were estimated at nearly 1 Billion USD.

(Apologies for posting this month’s update a few weeks later than usual – sometimes life and work get in the way of blogging…)

Power Outages

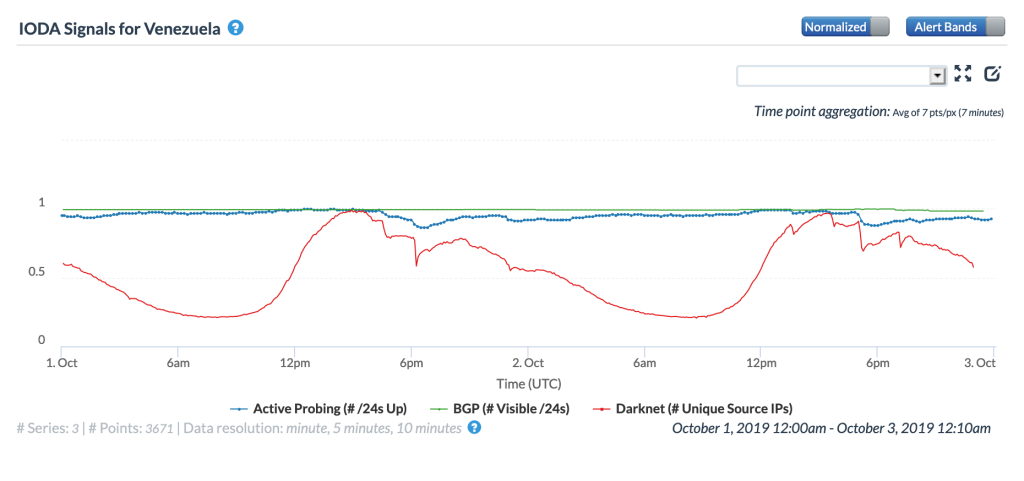

We have observed Internet disruptions in Venezuela in the past that were caused by the country’s unstable electrical power infrastructure, and October was no different. The figure below shows the impact of power outages that occurred on both October 1 & 2, both just before 1800 UTC. On both days, the BGP metric remains stable (indicating that the systems announcing the routes were unaffected by the power problems), but the Active Probing and Darknet metrics saw declines due to loss of connectivity within the last mile networks that the probes target and that originate the Darknet traffic.

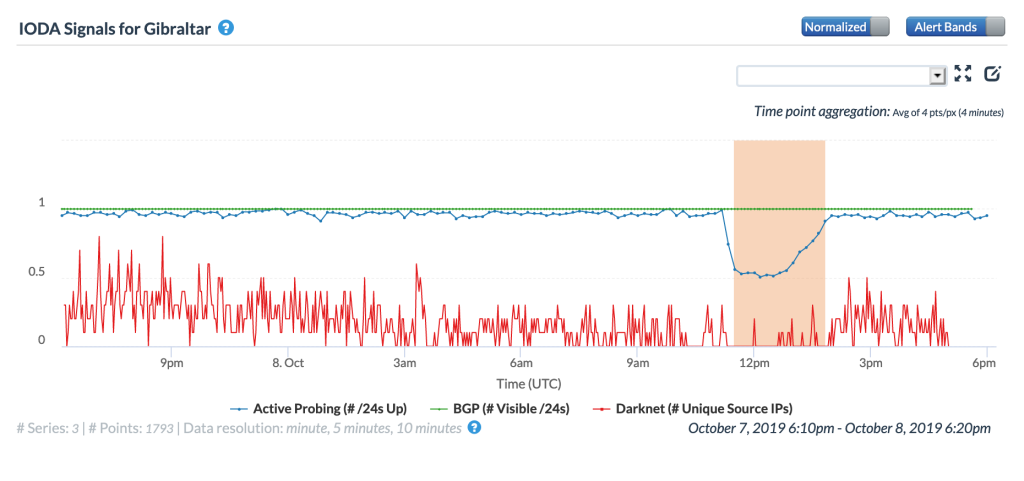

In Gibraltar, the country’s electricity authority took to Twitter to alert customers to an ongoing power outage, and to apprise them of the cause of the outage. The figures below show that the power outage likely started about a half hour before the Tweets were published, with a country-level Internet disruption in Gibraltar starting just after 1100 UTC. Connectivity returned to normal about three hours later.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Gibraltar, October 8

CAIDA IODA graph for Gibraltar, October 8

In California, regional power company Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) once again implemented “Public Safety Power Shutoffs“, noting:

“For public safety, it may be necessary for us to turn off electricity when gusty winds and dry conditions, combined with a heightened fire risk, are forecasted. … While customers in high fire-threat areas are more likely to be affected, any of PG&E’s more than five million electric customers could have their power shut off.”

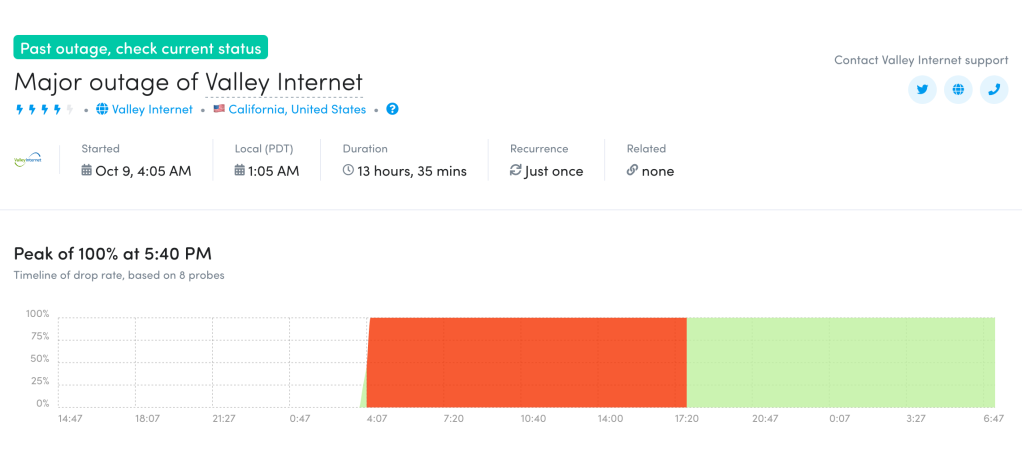

These power outages obviously have the ability to impact local Internet connectivity. As one such example (out of several over the course of October), network monitoring firm Fing observed a disruption at regional service provider Valley Internet (the d/b/a name of Personal Network Computing) lasting for more than half a day, as shown in the Tweet below from Fing’s @outagedetect account, as well as the figure below. The locations of the measured Internet service disruption aligned with the map of expected affected areas posted to the PG&E Outage Center on October 9, providing a high likelihood of correlation between the two events.

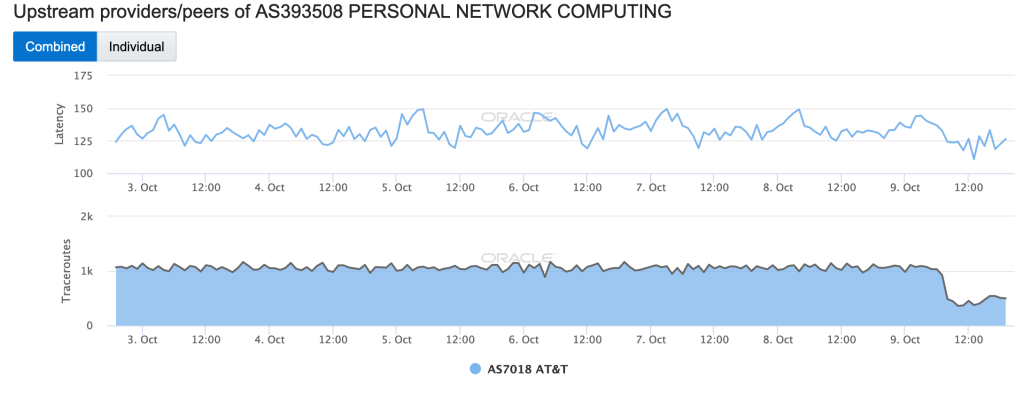

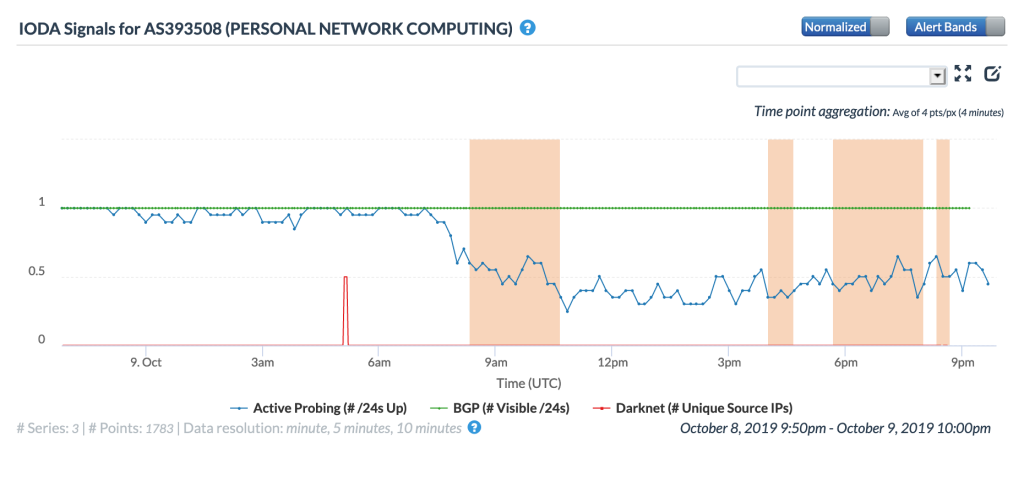

The localized network-level disruption was also observed through other network monitoring tools. The figures below show that both Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA recorded declines for the actively measured metrics during the course of the power outage and associated disruption.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS393508, October 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS393508, October 9

Cable Cuts

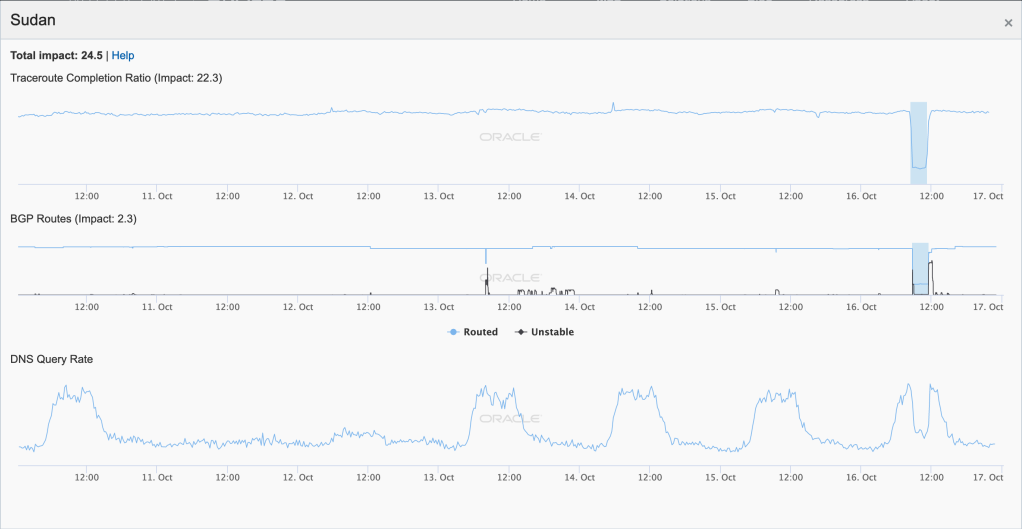

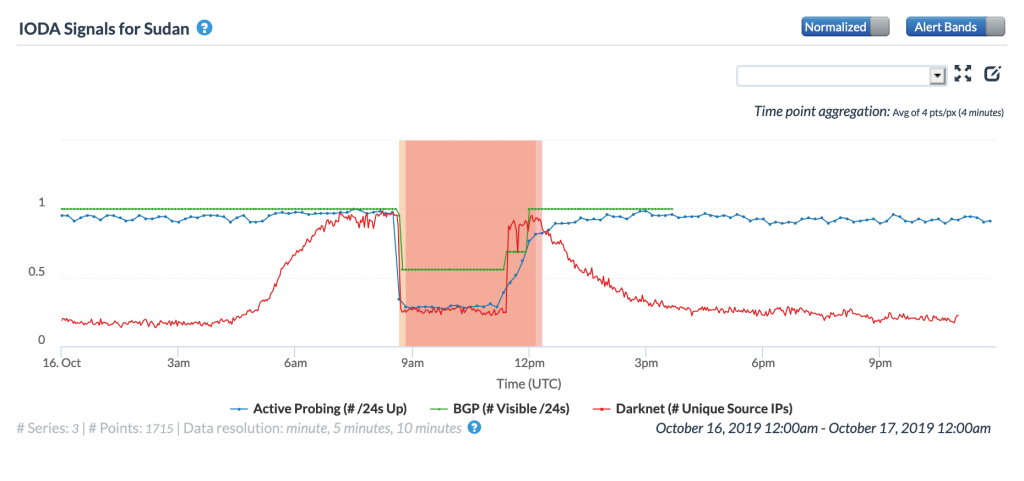

On October 16, Sudan suffered a nearly three-hour Internet disruption. The figures below show a sharp decline in the three metrics measured by Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Sudan, October 16

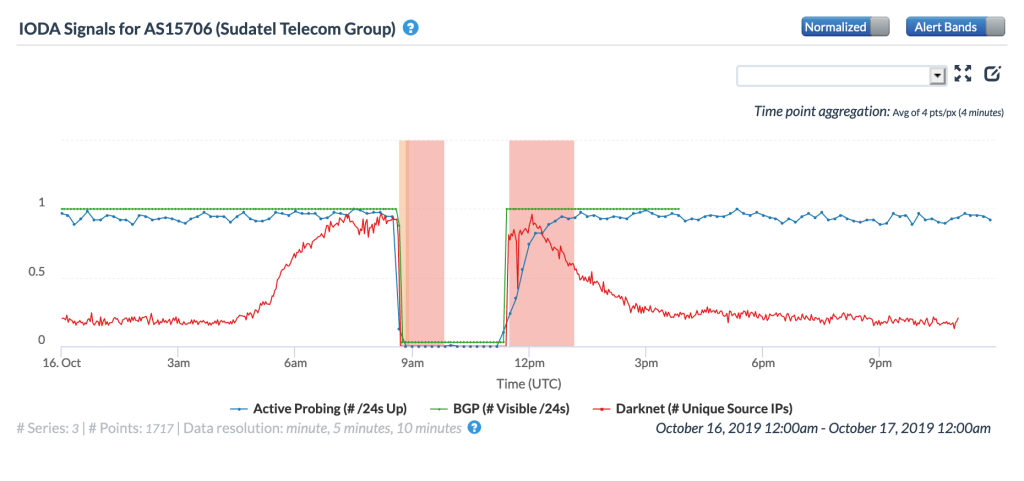

CAIDA IODA graph for Sudan, October 16

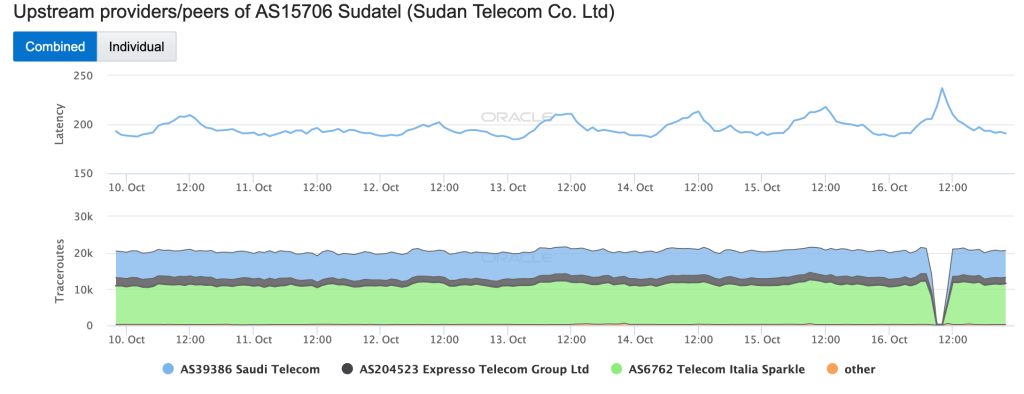

A local contact reported that the disruption was caused by a “double cut” to a Sudatel fiber ring, and that MTN was also impacted by the fiber cut. The figures below illustrate the impact of the cut to both Sudatel and MTN Sudan.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS15706, October 16

CAIDA IODA graph for AS15706, October 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS36972, October 16

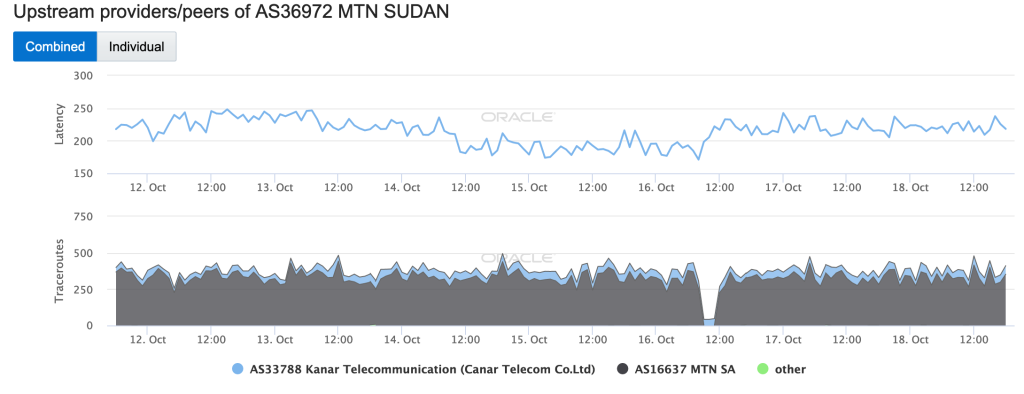

CAIDA IODA graph for AS36972, October 16

And while we don’t often cover it here, these Internet disruptions do impact local users and businesses. As one example, CashQ, a mobile payment application, was unable to provide services to its users as a result of this Internet disruption in Sudan, as it explained on Twitter.

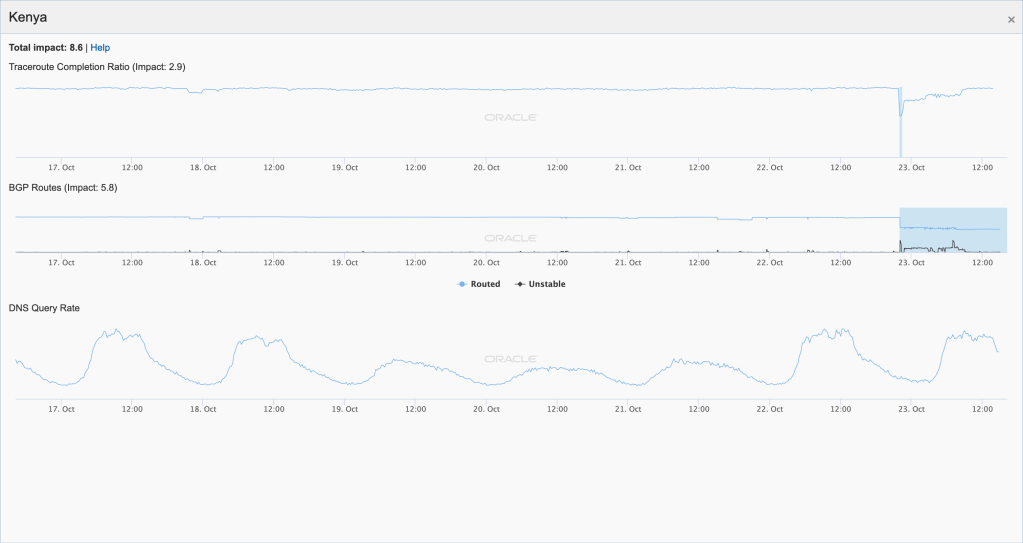

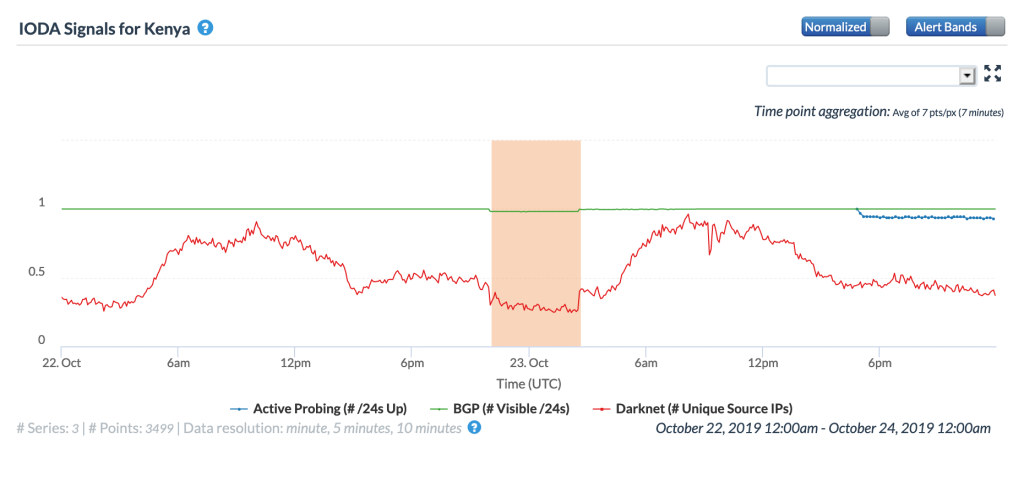

A week later, a problem with the SEACOM Subsea Cable System disrupted Internet connectivity in Kenya and Comoros on October 23. In a series of Tweets (1, 2, 3), @SEACOM stated that the outage began at 2200 UTC on October 22, impacting its subsea cable system between Mombasa [Kenya] and Zafarana [Egypt], and forcing it to route traffic over West coast transmission links. The figures below show that both Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA detected a minor perturbation in the BGP metric at a country level for Kenya around the time that the outage occurred. Oracle’s measurements also recorded a decline in successfully completed traceroutes to endpoints in the country, while a nominal impact was seen in the Darknet sources metric measured by CAIDA.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Kenya, October 23

CAIDA IODA graph for Kenya, October 23

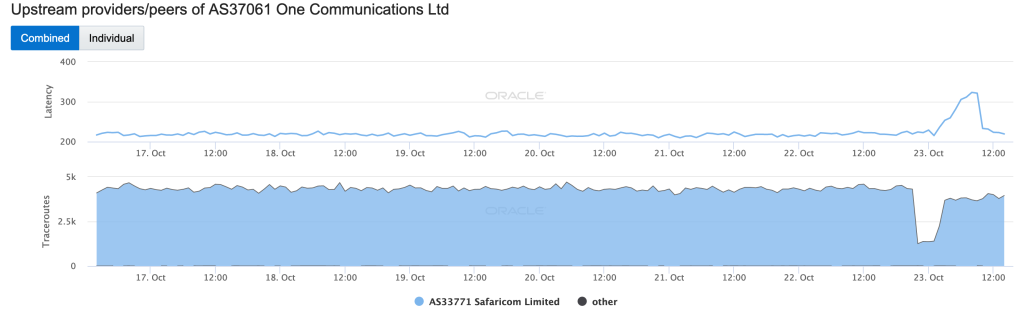

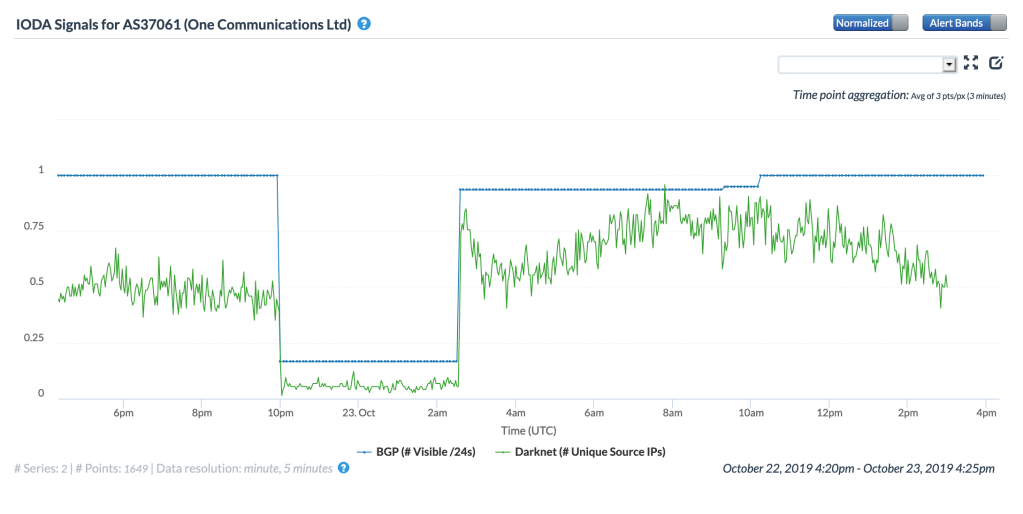

One Communication/Safaricom is a leading telecommunications provider in Kenya, and is clearly reliant on the SEACOM cable for international Internet connectivity. The Oracle Internet Intelligence graph in the figure below shows a significant drop in completed traceroutes to endpoints within the network, while the CAIDA IODA graph shows a near complete loss of visible networks associated with the autonomous system visible in the routing table. CAIDA also shows a concurrent drop in the Darknet Sources metric, indicating that systems within that network were no longer probing the address space used by CAIDA’s Network Telescope.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS37061, October 23

CAIDA IODA graph for AS37061, October 23

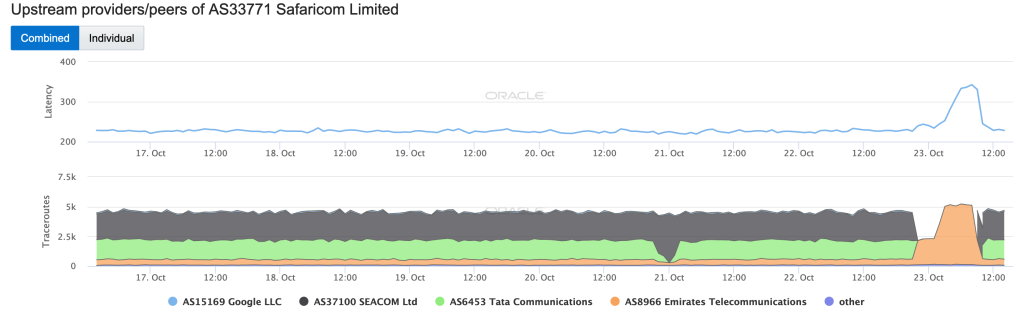

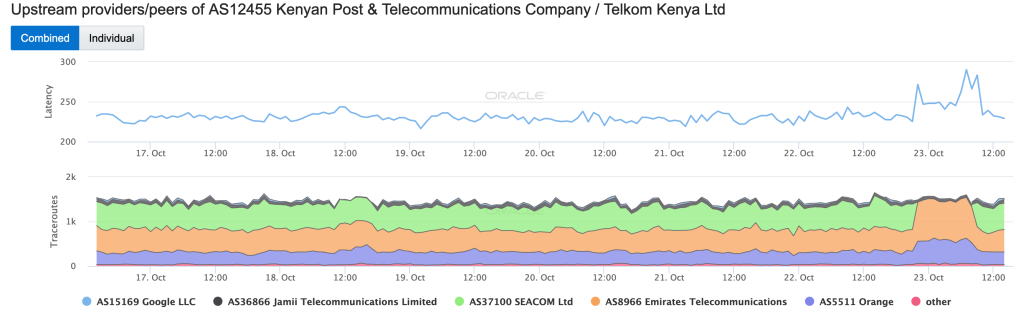

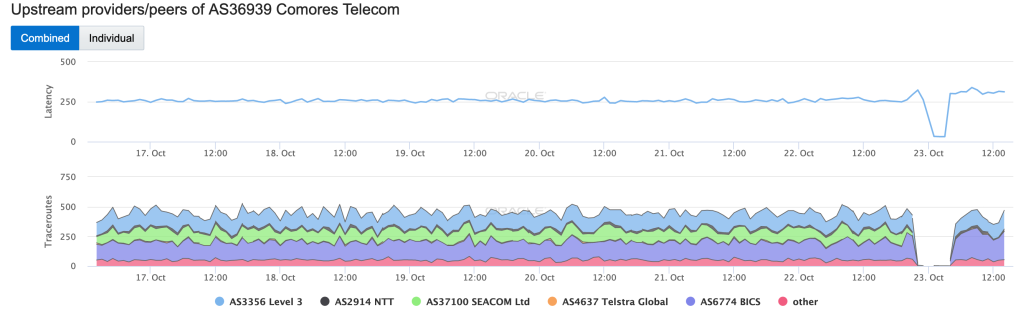

Impacted networks in Kenya shifted upstream providers during the cable outage, resulting in increased latency for traffic to these networks. The figures below illustrate the latency impact for two networks: Safaricom saw latency increase by approximately 50% as it shifted to Emirates Telecommunications as its primary upstream provider, while Kenyan Post/Telkom Kenya saw latency increase by approximately 10-20% as it moved to Emirates Telecommunications.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS33771, October 23

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS12455, October 23

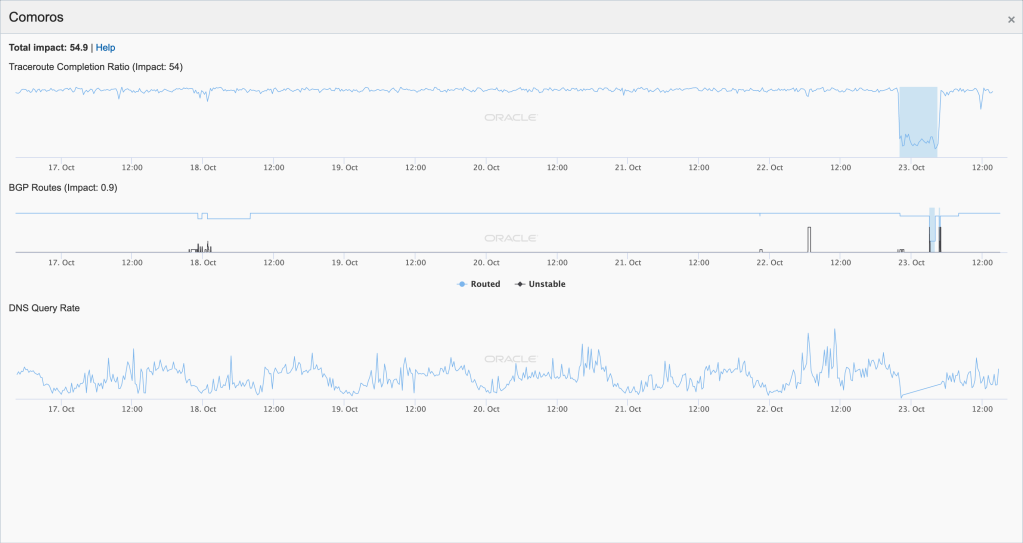

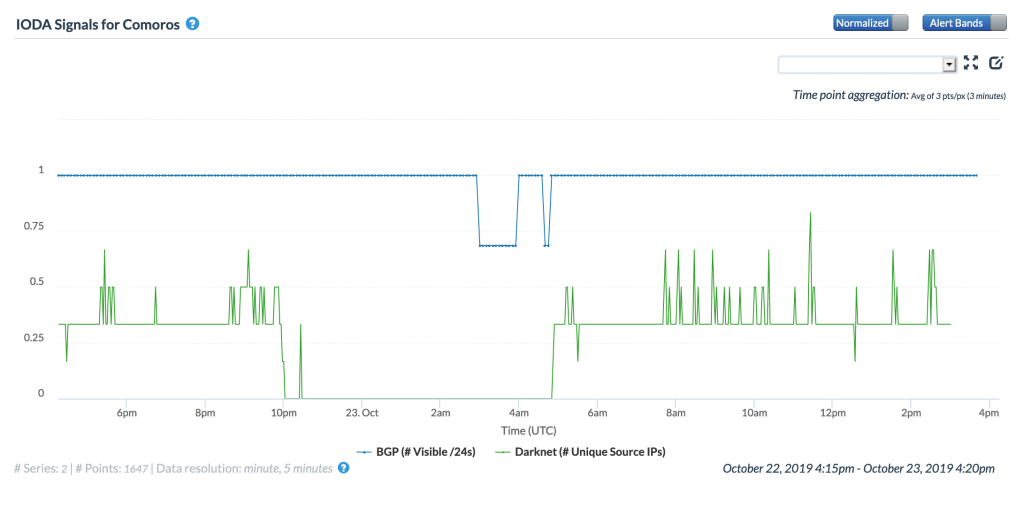

As noted above, Comoros was also impacted by this problem with the SEACOM submarine cable. The Oracle Internet Intelligence figure below shows a significant impact to the Traceroute Completion Ratio metric, and a very slight impact to the BGP metric (with the exception of a sharp but brief drop). The CAIDA IODA figure below shows a somewhat more significant impact to the BGP metric, with a similar sharp but brief drop towards the end of the disruption period.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Comoros, October 23

CAIDA IODA graph for Comoros, October 23

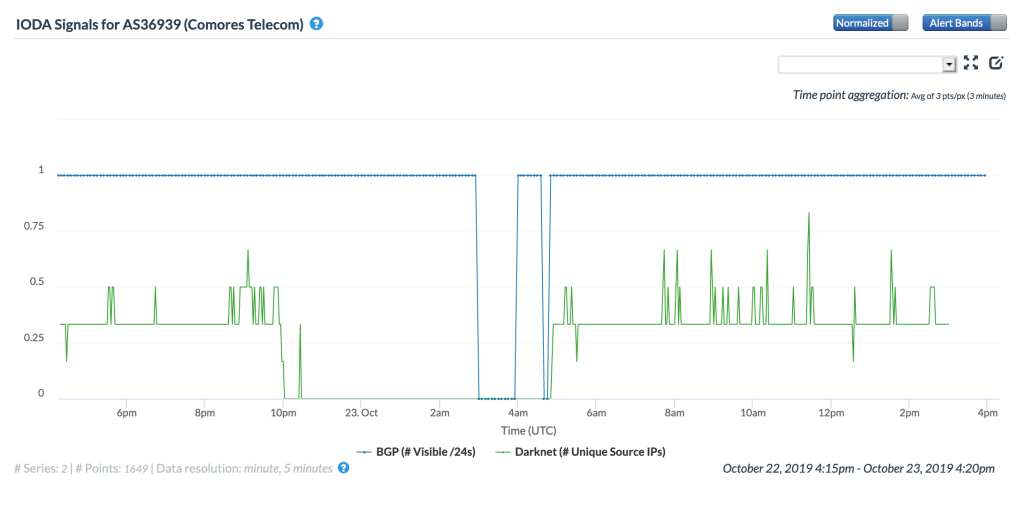

Comores Telecom was also heavily affected, with both Oracle and CAIDA showing a near complete outage for the networks, as seen in the figures below.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS36939, October 23

CAIDA IODA graph for AS36939, October 23

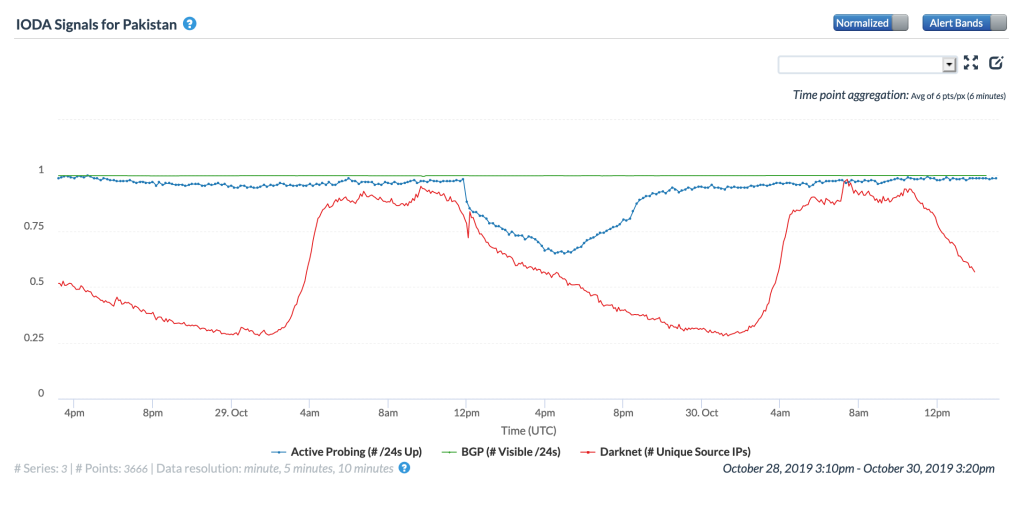

Pakistan experienced an Internet disruption on October 29, due to a fault in an international submarine cable, as explained in a Tweet from @PTAofficialpk, a Twitter account associated with the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority. The figure below shows the impact on CAIDA IODA’s Active Probing to endpoints within the country. There was no obvious routing impact, and Darknet traffic also appeared to be unaffected.

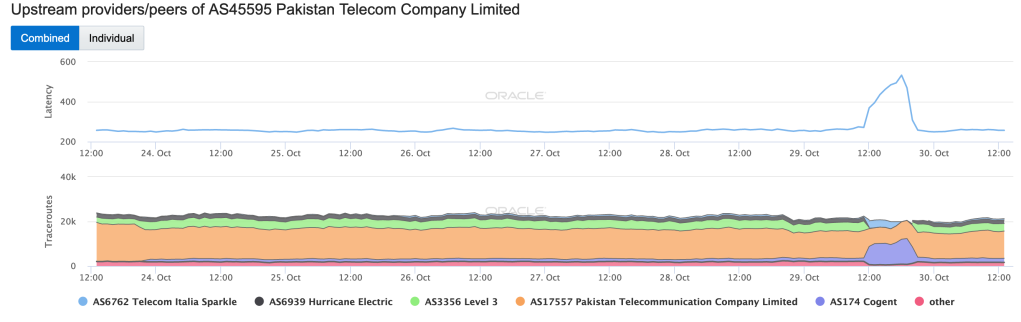

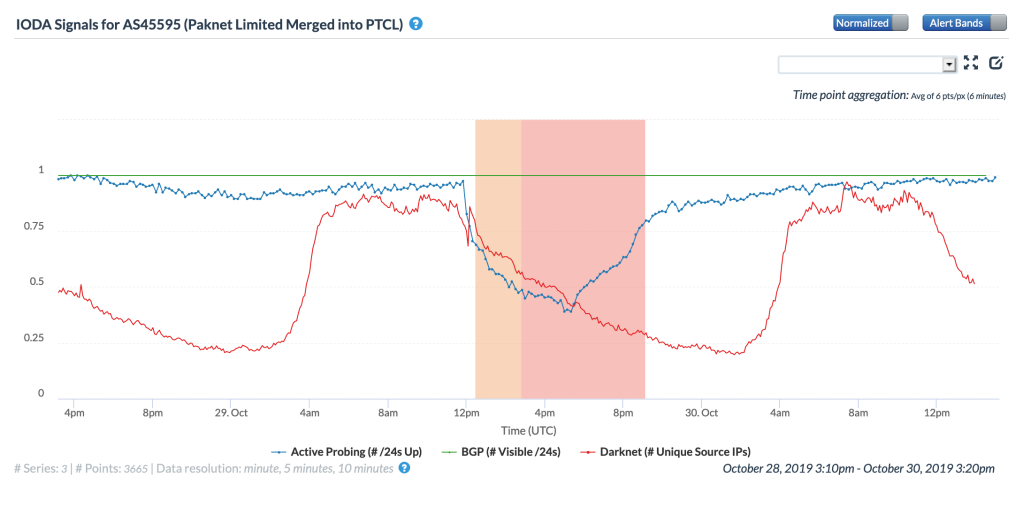

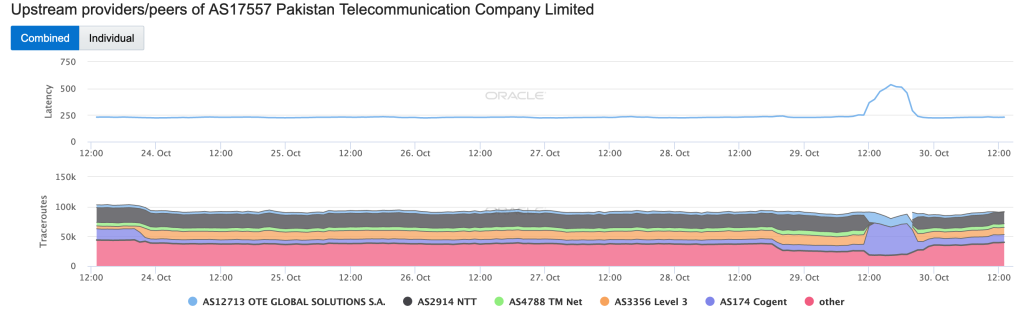

According to a subsequent Tweet from the Pakistan Telecom Company (PTCL), the cable fault occurred on the SMW-4 cable. The figures below show the impact across two of PTCL’s autonomous systems, with Oracle Internet Intelligence showing increased latencies as more traffic flowed over Cogent as an upstream provider, while CAIDA IODA showed a decline in the Active Probing metric.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS45595, October 29

CAIDA IODA graph for AS45595, October 29

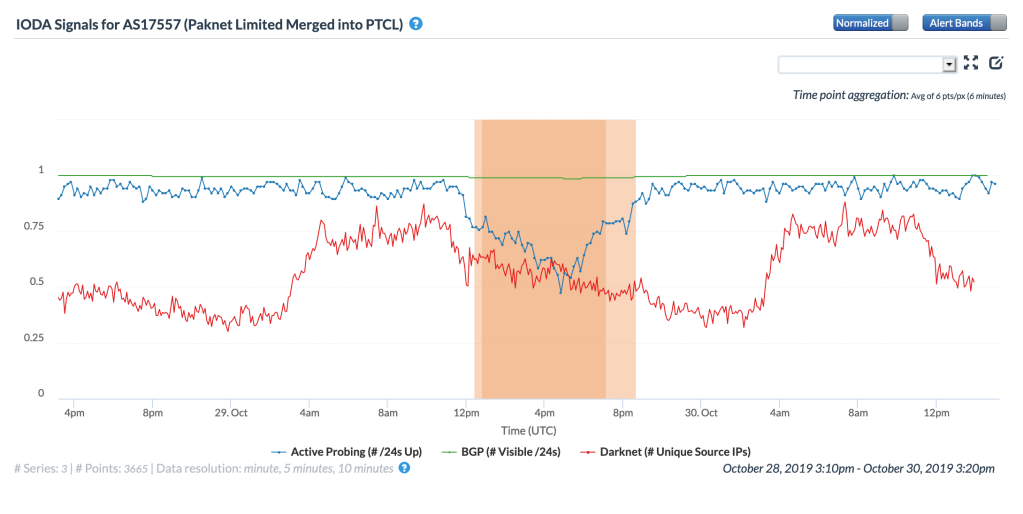

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS17557, October 29

CAIDA IODA graph for AS17757, October 29

A published article highlighted a local impact of this Internet disruption, quoting a Tweet from Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) that explained that the the issues that the cable cut caused for PTCL ultimately resulted in an outage of PIA flight check-in systems across the country, forcing them to move to backup systems and manual processes and resulting in passenger delays.

Government Directed

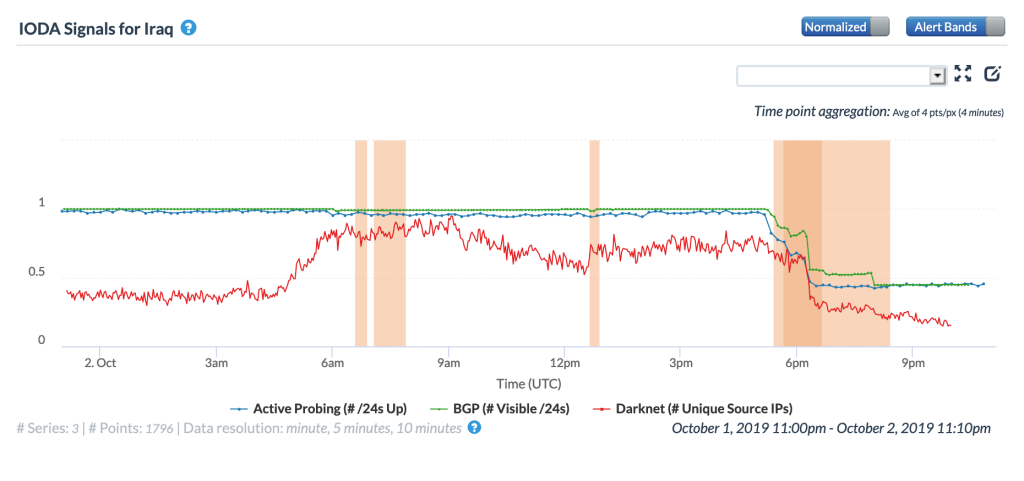

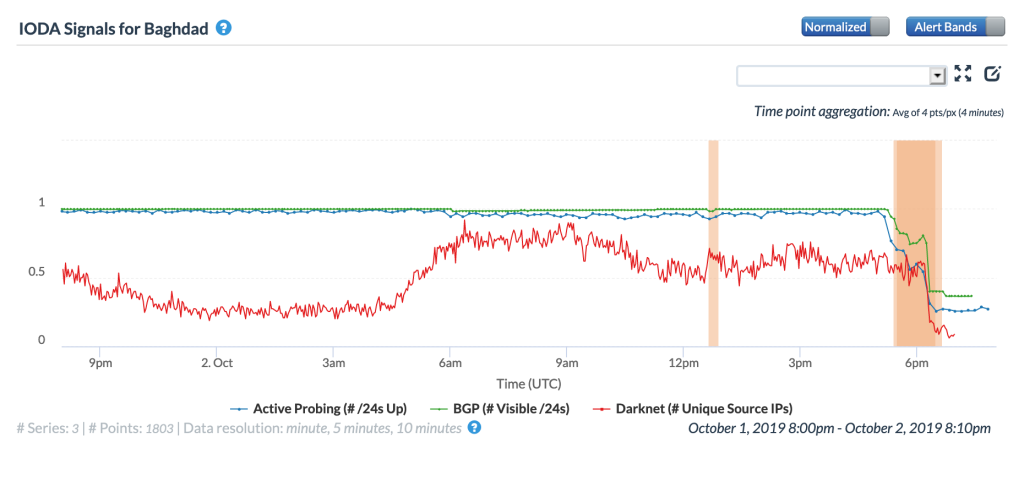

The most significant Internet disruption that occurred in October took place in Iraq, with connectivity impaired for over a week. Published accounts (AlMonitor, CPJ, AccessNow) reported violent protests over unemployment, government corruption, and a lack of basic services in Baghdad and other Iraqi cities on October 1-2, resulting in over a dozen deaths and hundreds of injuries. In response to the protests, the Iraqi government imposed a near total Internet shutdown on October 2, apparently beginning at approximately 1600 UTC, as shown in the figures below. The figures also illustrate that the shutdown did not completely remove Iraq from the Internet. This is reportedly due to the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) Ministry of Transportation and Communications rejection of the call by the Iraqi federal government to cut off the Internet in the Kurdistan Region. The Kurdistan region’s connection to international communications infrastructure is separate from the one in southern and central Iraq.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Iraq, October 2

CAIDA IODA graph for Iraq, October 2

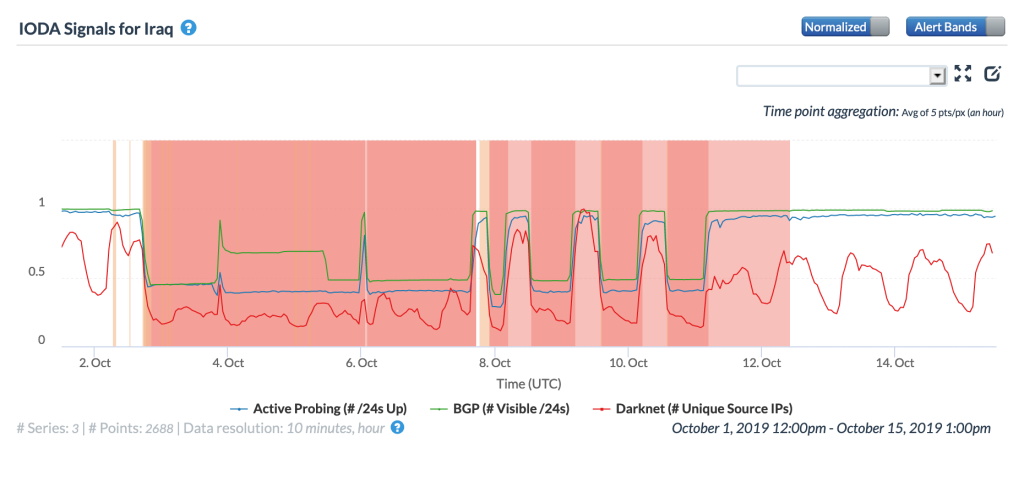

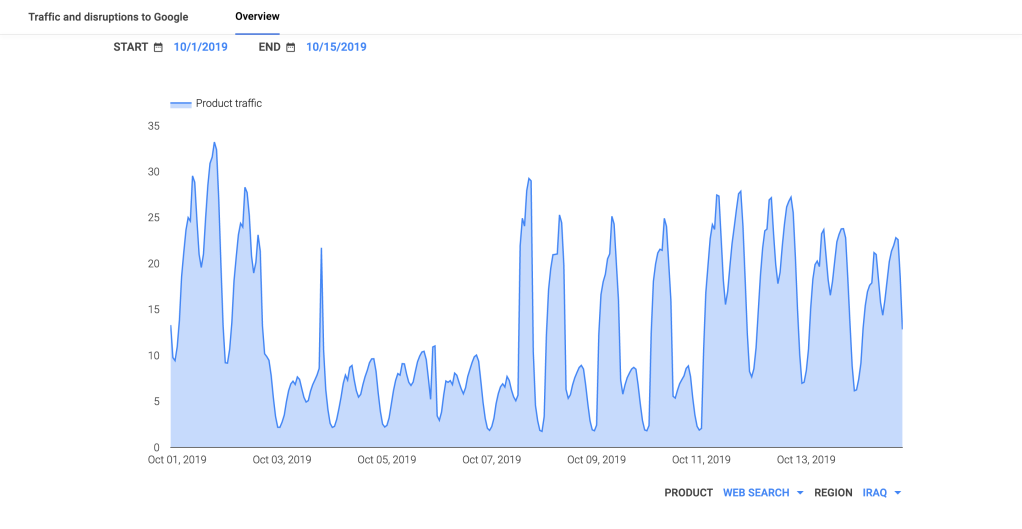

As the figures below show, the Internet disruption lasted for over a week, with measured metrics returning to “normal” levels on October 11. After a few brief restorations of connectivity on October 3 and 6, Internet availability settled into a “curfew” model, as described by NetBlocks, with access returning during the workday, and then being cut again in the evening.

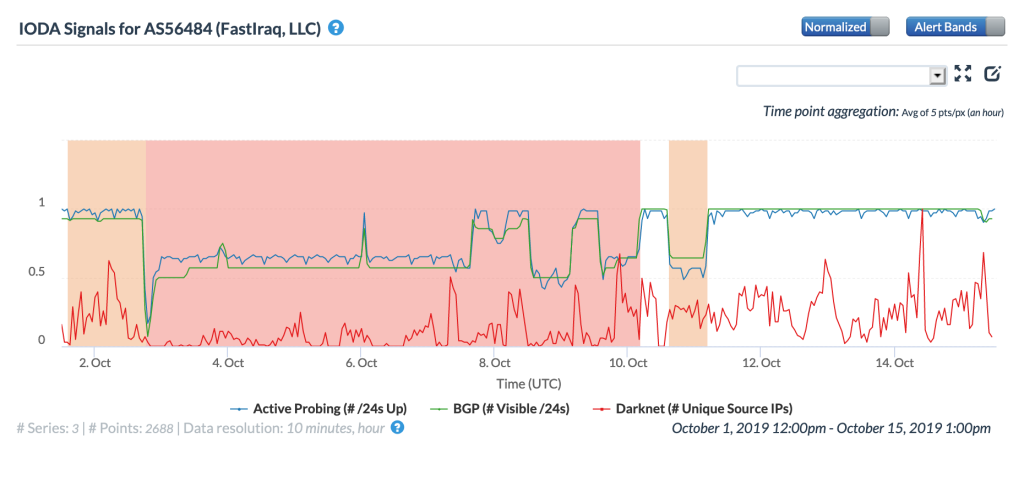

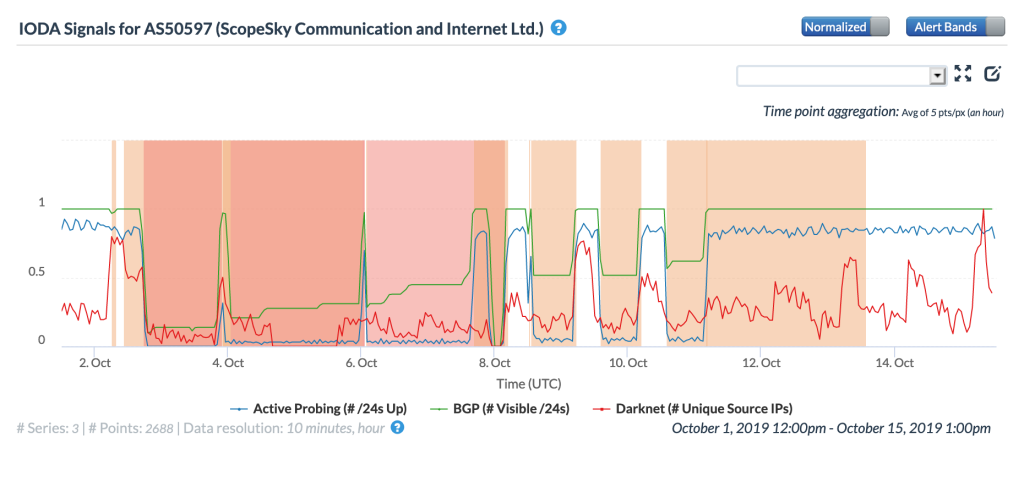

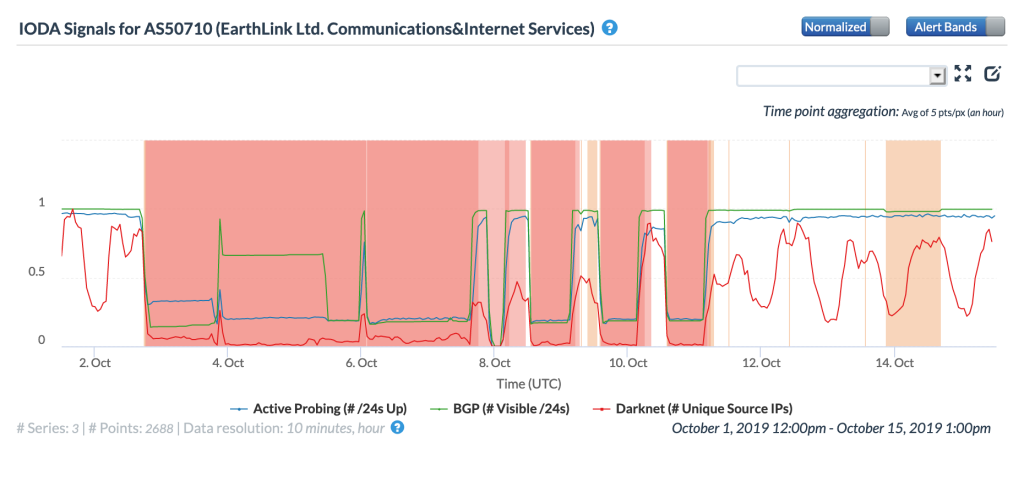

Unsurprisingly, trends at a network level are nearly identical to the activity seen at a country-level. The figures below show measurements across three major Internet service providers in Iraq, with BGP and Active Probing patterns that appear very similar to the ones seen in the country-level graph above.

CAIDA IODA graph for AS56484, October 1-15

CAIDA IODA graph for AS50597, October 1-15

CAIDA IODA graph for AS50710, October 1-15

One published report explained that some Iraqis initially attempted to use VPN technology to circumvent connectivity restrictions, while those that could afford to made use of satellite-based Internet connectivity. Others queued content posts and videos within the social media and chat applications on their mobile devices, with the expectation that they would be sent when these devices were finally able to connect to the Internet.

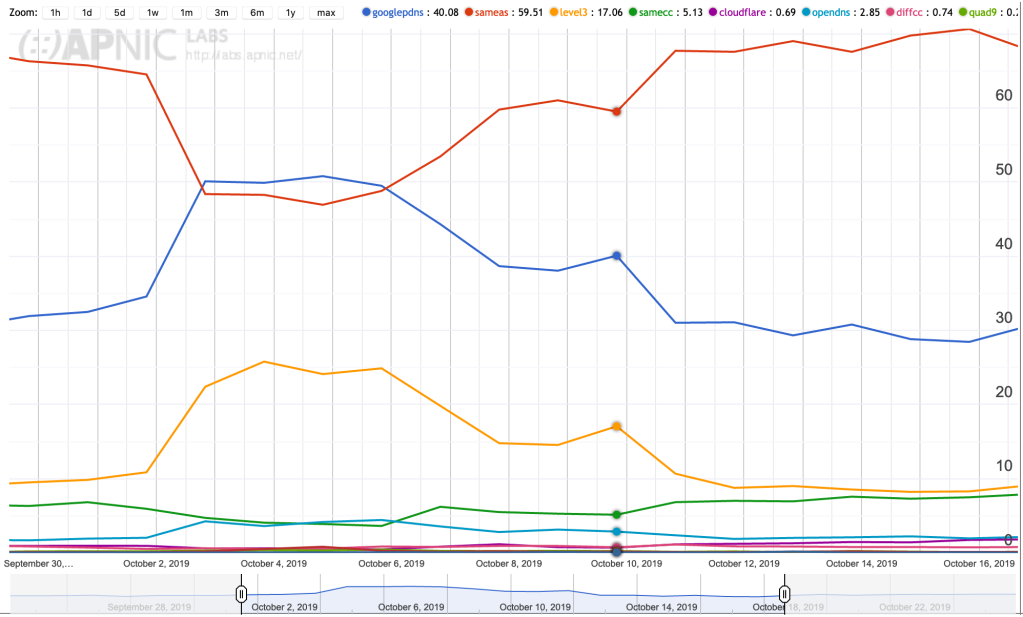

Based on measurements done by Geoff Huston at APNIC Labs, it also appears that some Iraqi users are configuring third-party public DNS resolver services as backups in the event that the resolvers at their providers (generally configured as the default) become unavailable. Based on Huston’s experiments, the figure below shows that prior to October’s Internet disruption, approximately 65% of DNS requests made by Iraqi users reached authoritative DNS servers through a resolver in the same autonomous system (“sameas”) – that is, the user’s ISP. Approximately 30% were made through Google’s 8.8.8.8 resolver (“googlepdns”), while less than 10% were made through CenturyLink/Level 3’s open public resolver (“level3”). However, for a multi-day period after the disruption started, the percentage of DNS requests from Iraqi users coming through Google surpassed those coming from resolvers at the user’s service provider. Usage of Level 3’s resolver also increased during this period. The graph shows that request volume through ISP resolvers returned to previous levels in line with the restoration of connectivity in Iraq. (It was pointed out that the conclusion reached here was incorrect: “You need to look at that in terms of absolute values. The relative values are biased, as the denominator changed. Those affected by the shutdown stopped reporting. In this case, The Kurdish ISPs were not shutdown. It may be the case that the distribution in those networks is different, and that was the reason for the shift, and not actual changes by the users.” The original text and figure remain for transparency, but should be considered deprecated.)

As noted in the introduction, this shutdown had a significant impact on the Iraqi economy, with an article in the International Business Times placing the estimated impact at nearly a billion dollars. The article highlights the financial pain experienced by members of the emerging digital economy in Iraq, including startups, e-commerce sites, online delivery companies and couriers, and travel companies.

Other

Similar to previous months, several additional less-well attributed Internet disruptions were observed in October. For some, we could observe the disruption but could find no root cause information, or did not receive any response to social media outreach to impacted providers. For those included below, acknowledgement of the issue was made by the providers through their social media channels, even if few details were given.

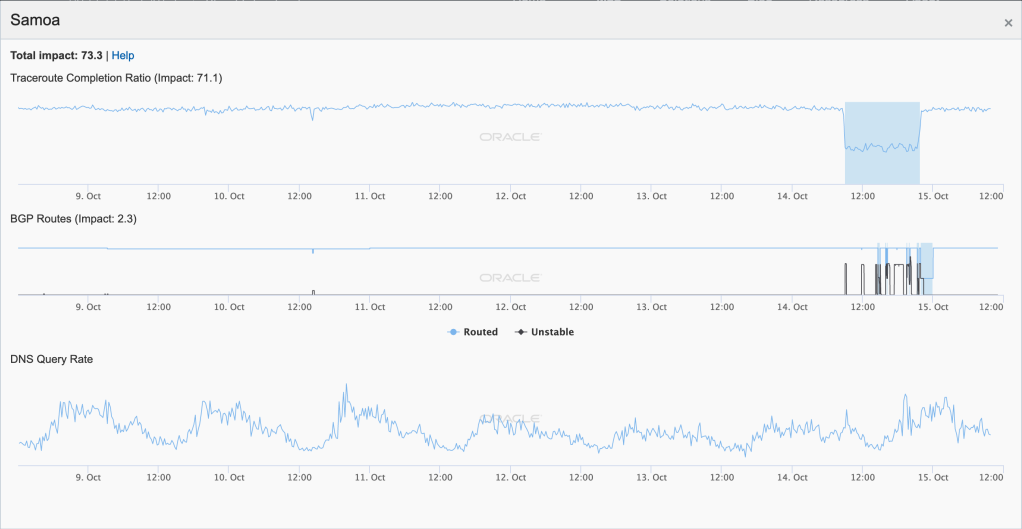

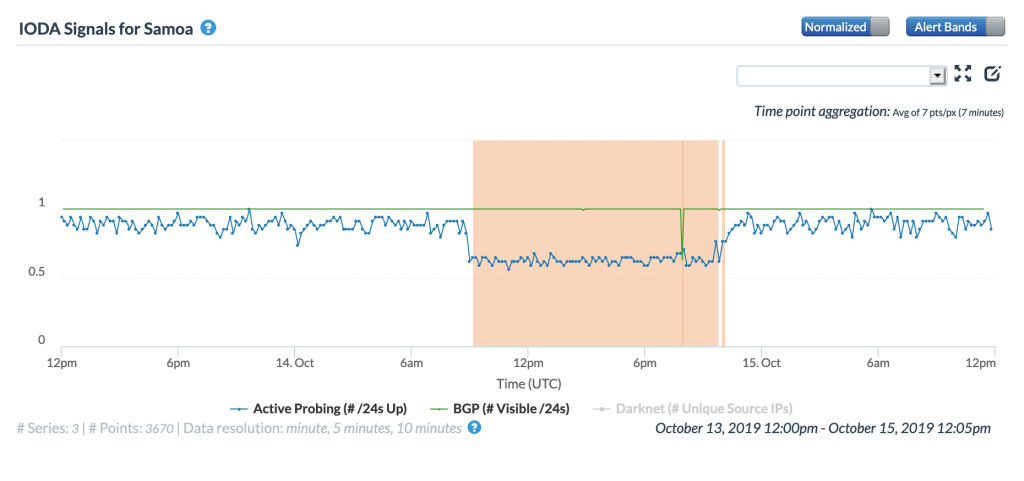

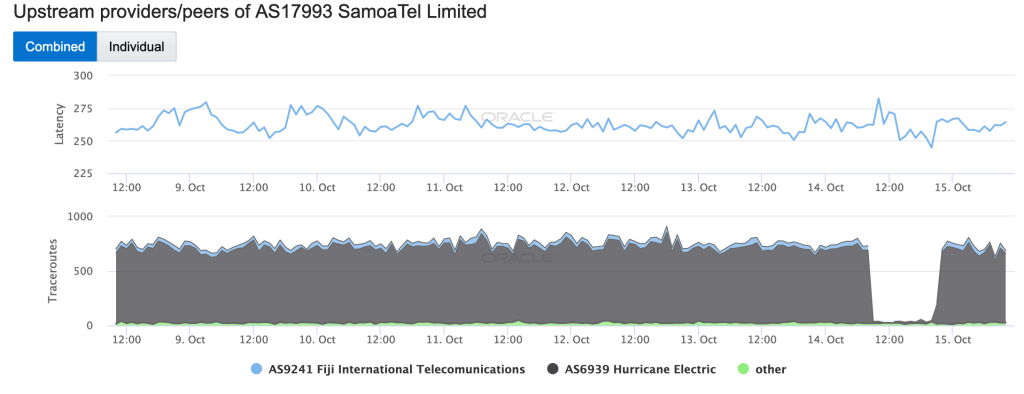

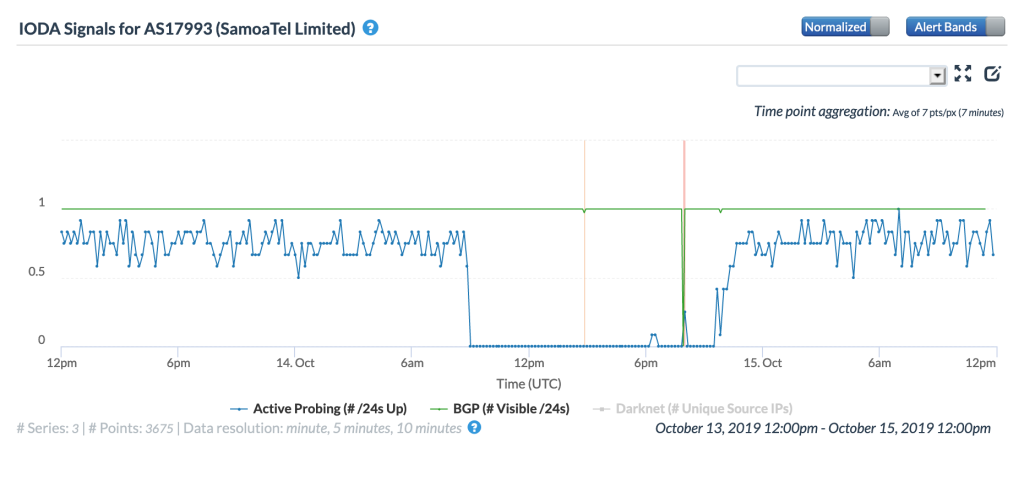

On October 14, SamoaTel/Bluesky Samoa informed users via Facebook and Twitter of an disruption to fixed Internet services. Unfortunately, no specific information about what caused this disruption was provided. The figures below show that while a nearly complete outage was seen at a network level, the impact was less significant at a country level.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Samoa, October 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Samoa, October 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS17993, October 14

CAIDA IODA graph for AS17993, October 14

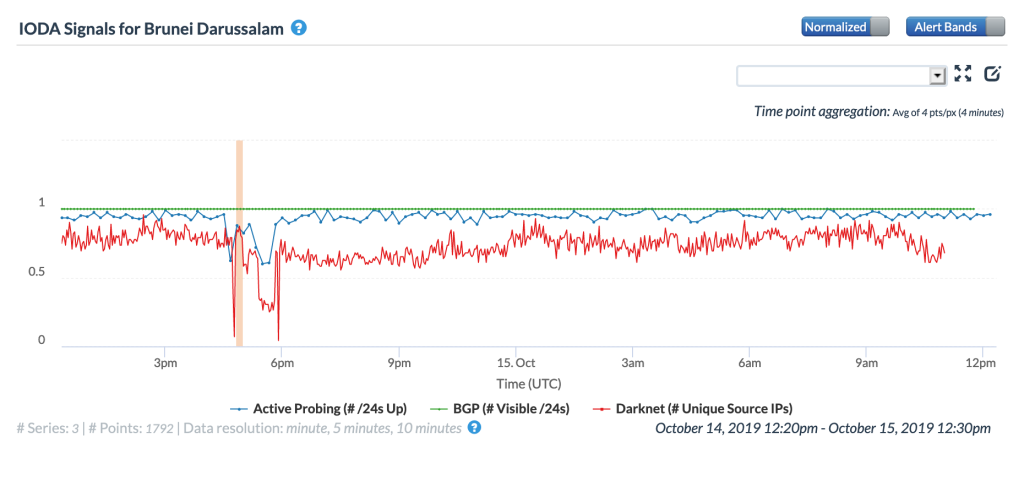

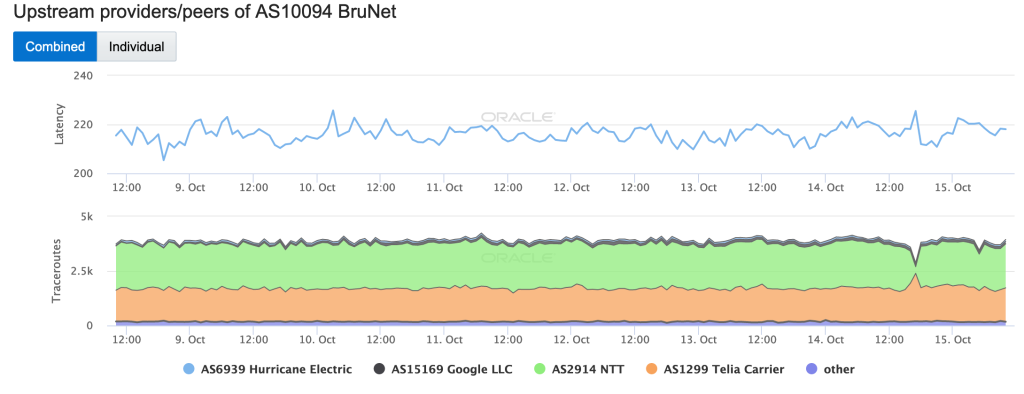

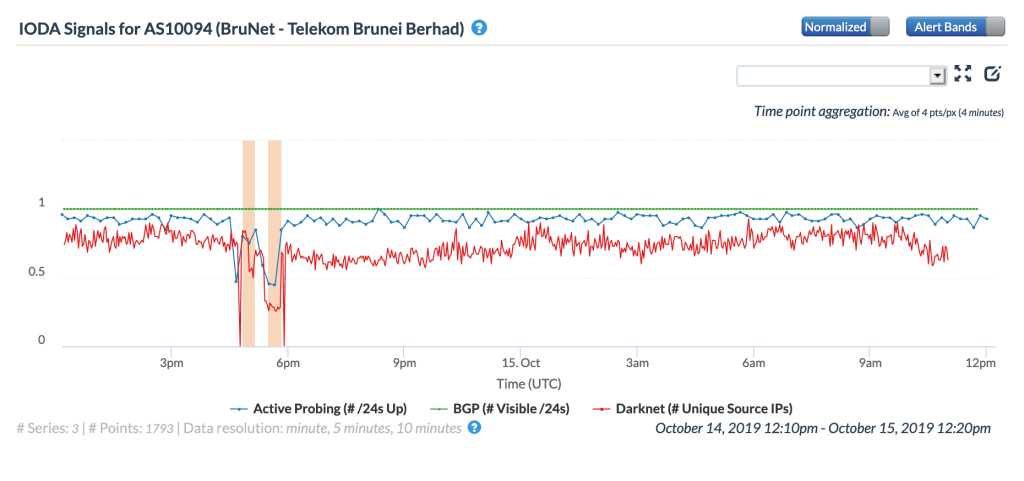

Also on October 14, Telekomn Brunei (TelBru) apologized to users via Twitter for downtime for broadband services apparently caused by a third-party service provider. The figures below show that the disruption was partial at both a country and network level, and fairly brief, lasting just a couple of hours. To its credit, TelBru regularly posts updates to Twitter (@telbru_bn) alerting customers of upcoming downtime to to maintenance activities.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Brunei, October 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Brunei, October 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS10094, October 14

CAIDA IODA graph for AS10094, October 14

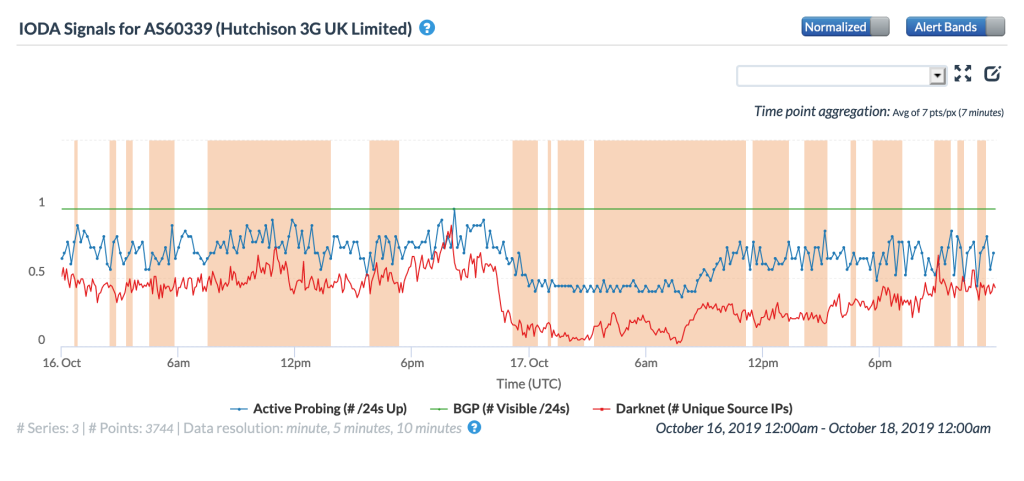

Internet monitoring firm Fing tracked a 15+ hour Internet disruption at provider Three UK that started the evening of October 16, lasting until mid-day on October 17.

The figure below shows the impact of disruption at a network level, with drops seen in the Active Probing and Darknet metrics. @ThreeUK acknowledged the network disruption in a Tweet, but failed to provide any additional information about what happened.

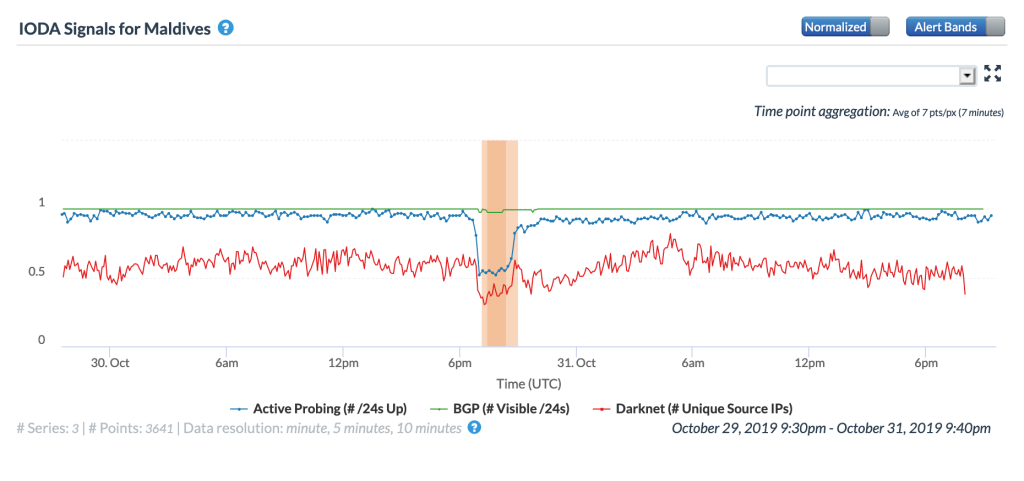

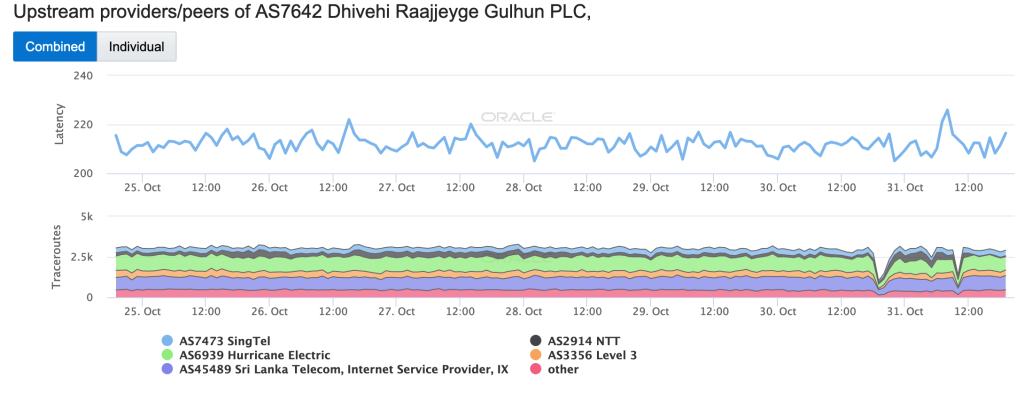

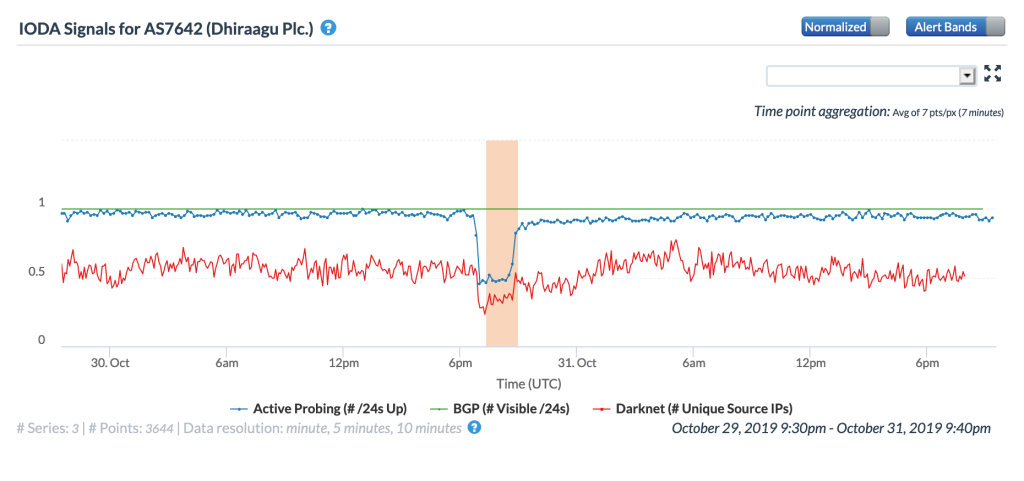

And near the end of the month, Maldives provider Dhiraagu alerted users via Twitter and Facebook to service degradation on mobile & fixed broadband services.

The figures below show that, similar to the TelBru issue above, the disruption was partial at both a country and network level, and fairly brief, again lasting just a couple of hours.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Maldives, October 30

CAIDA IODA graph for Maldives, October 30

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS7642, October 30

CAIDA IODA graph for AS7642, October 30

Conclusion

While both Internet outages and Internet shutdowns rob users of the ability to communicate with others, purchase goods and services, and consume media, there are significant differences between the two types of disruptions. In general, outages are unintentional or accidental disruptions to Internet connectivity – in the case they are intentional, it is generally due to infrastructure or network maintenance. Regardless, they are generally short lived, as impacted providers scramble to address the underlying issues as much as they have the ability to.

However, Internet shutdowns are the intentional disruption of Internet connectivity at the direction of a local, state, or national government, and often last for several days, if not weeks or months. These shutdowns have significant human rights impacts for citizens of the affected country, including limiting freedom of expression online, as well as significant economic impacts, with estimated costs running into multiple millions of (US) dollars each day the Internet is unavailable, as well as reducing the likelihood of future international investment within the country.

With the world increasingly watching, governments need to explore alternative ways of addressing the underlying issues that lead to Internet shutdowns, instead of leveraging these actions as a blunt-force policy tool. #KeepItOn