The conclusion of last month’s post noted “There was a noticeable absence of government-directed Internet disruptions in April. That is not to say that there were none, but those that did occur were not significant enough to be observed through publicly available tools.” This trend, which had also been observed over the prior few months, continued into May. (Unfortunately, this is not the case for June, but that will be covered in next month’s post.)

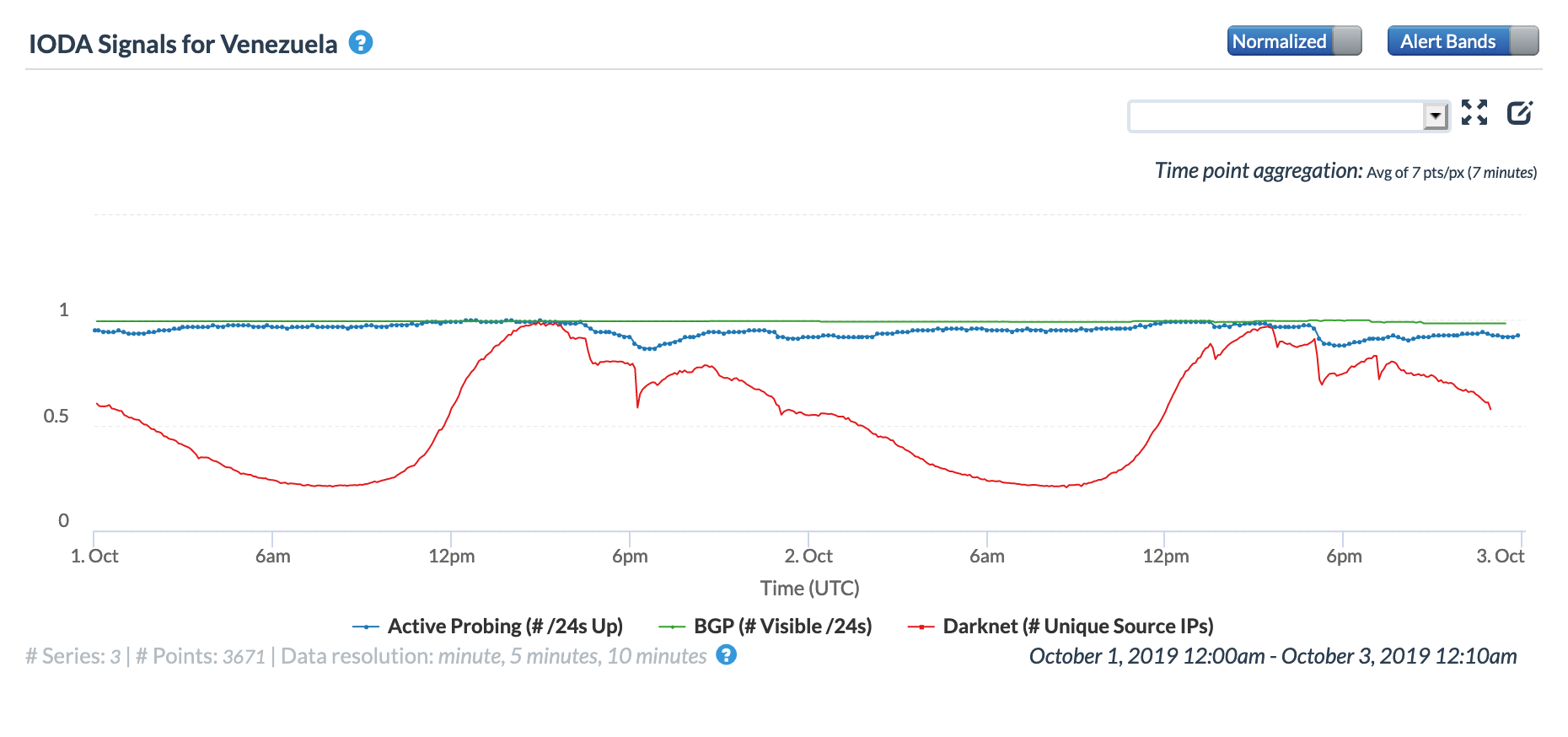

In May, a power outage in Venezuela once again disrupted Internet connectivity across the country, and a cyclone impacted connectivity in Bhutan. Fiber and submarine cable cuts (and repairs) caused Internet disruptions across multiple countries, as did unspecified network issues.

Power Outage

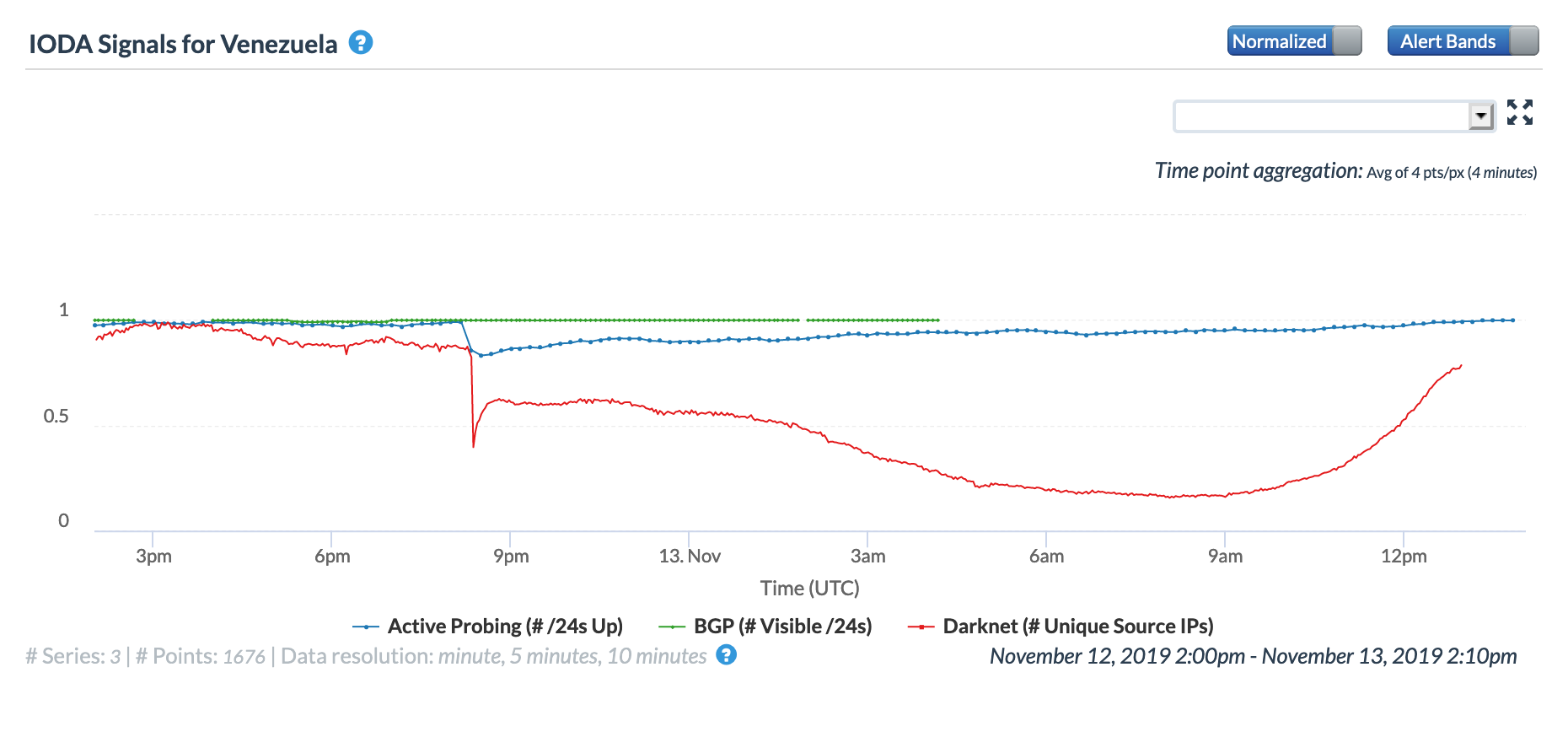

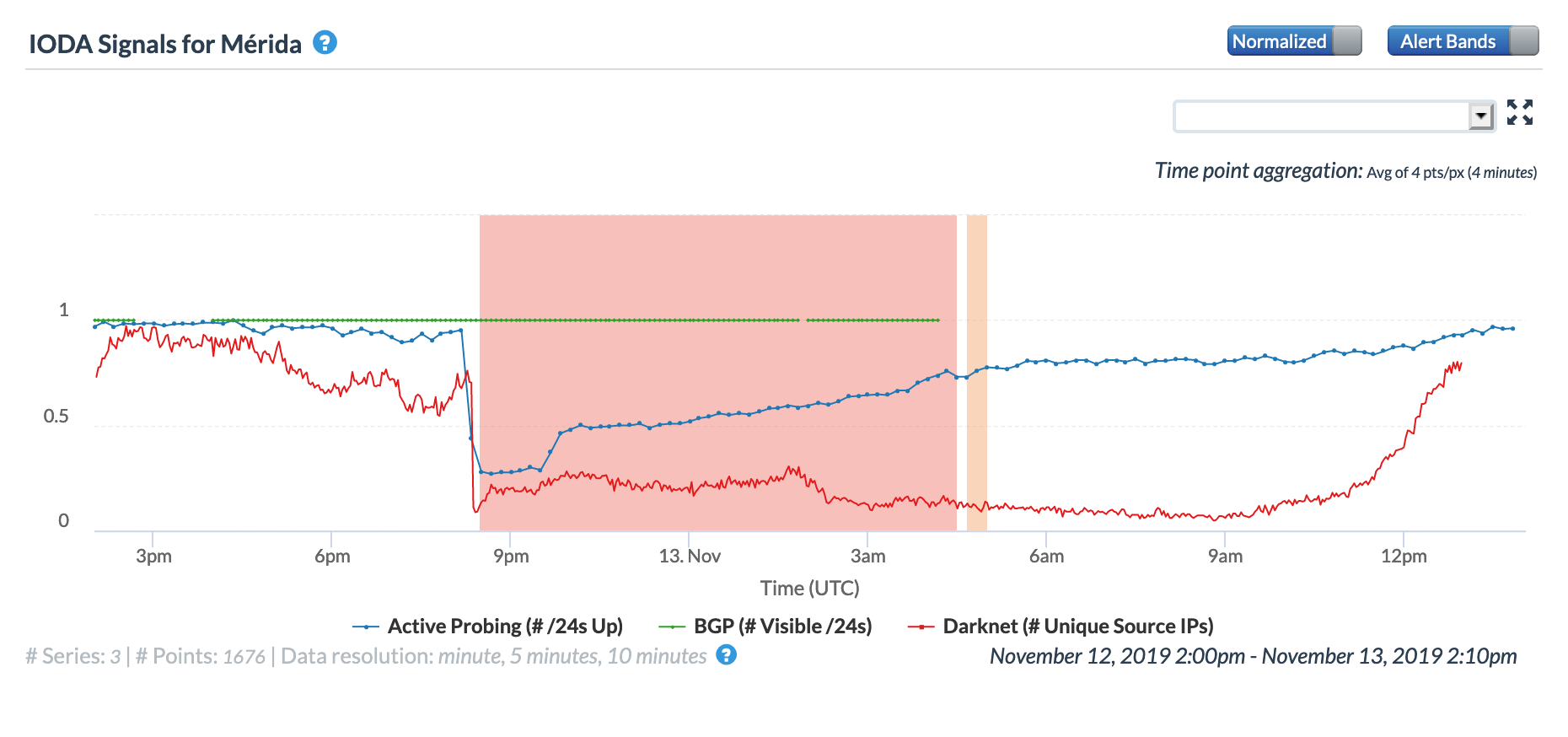

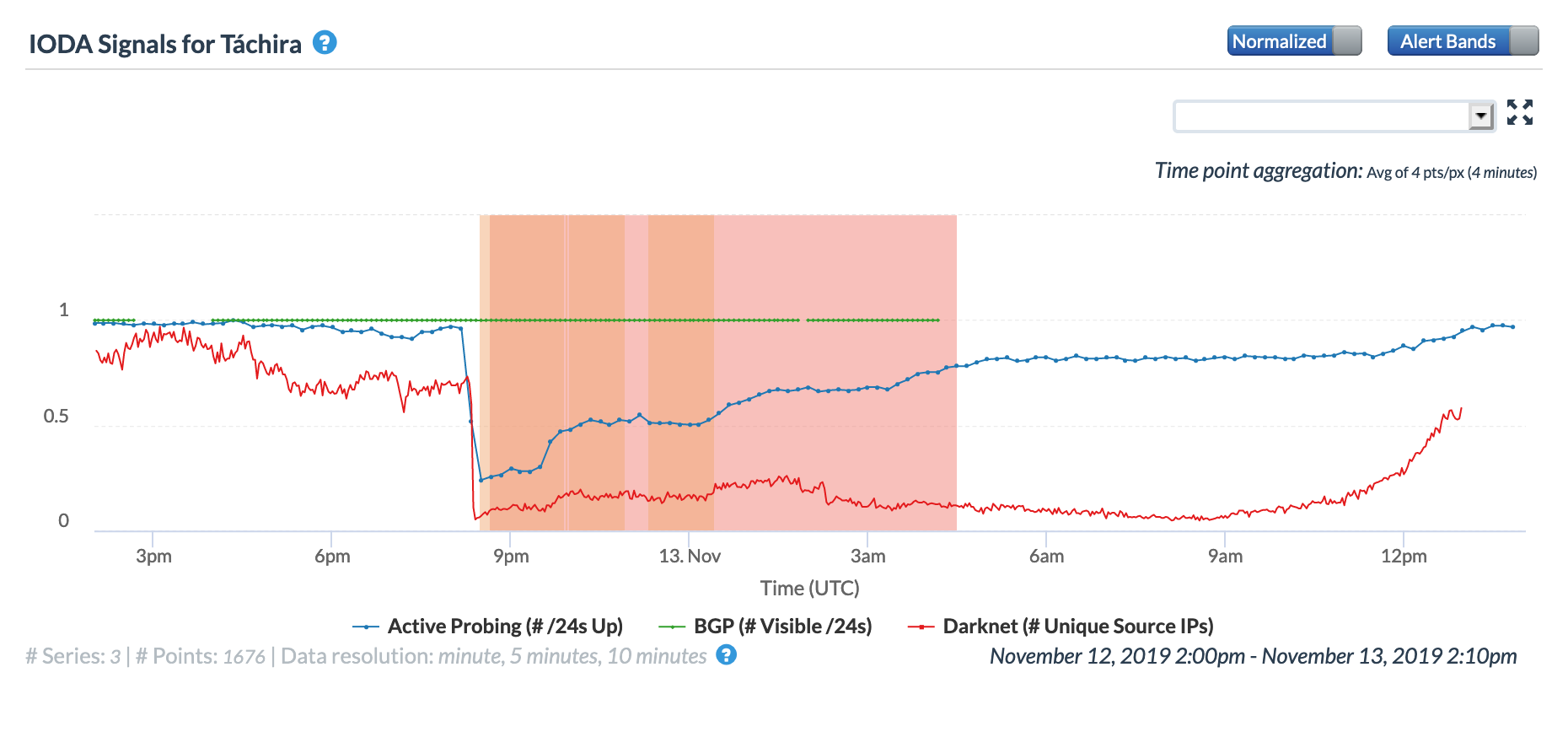

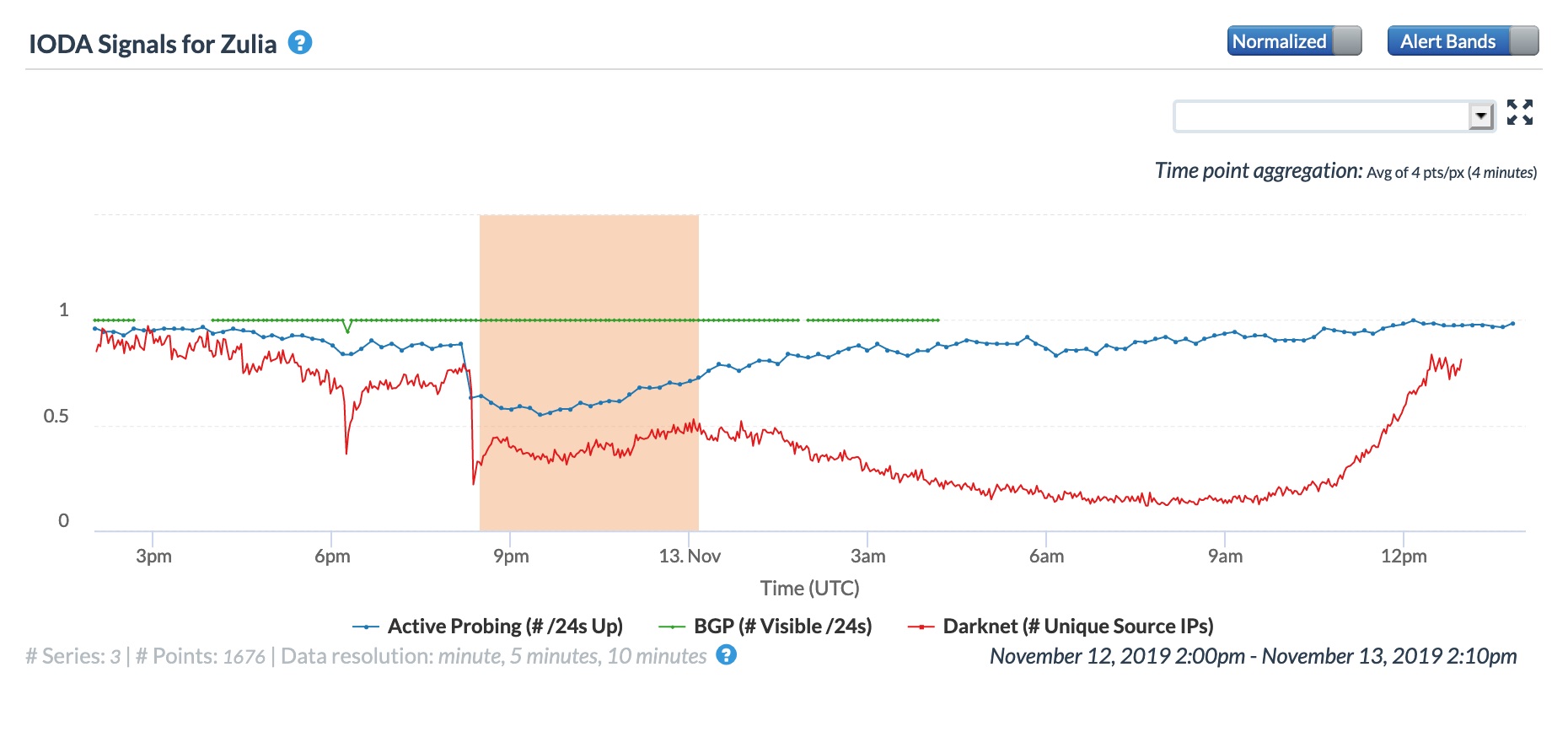

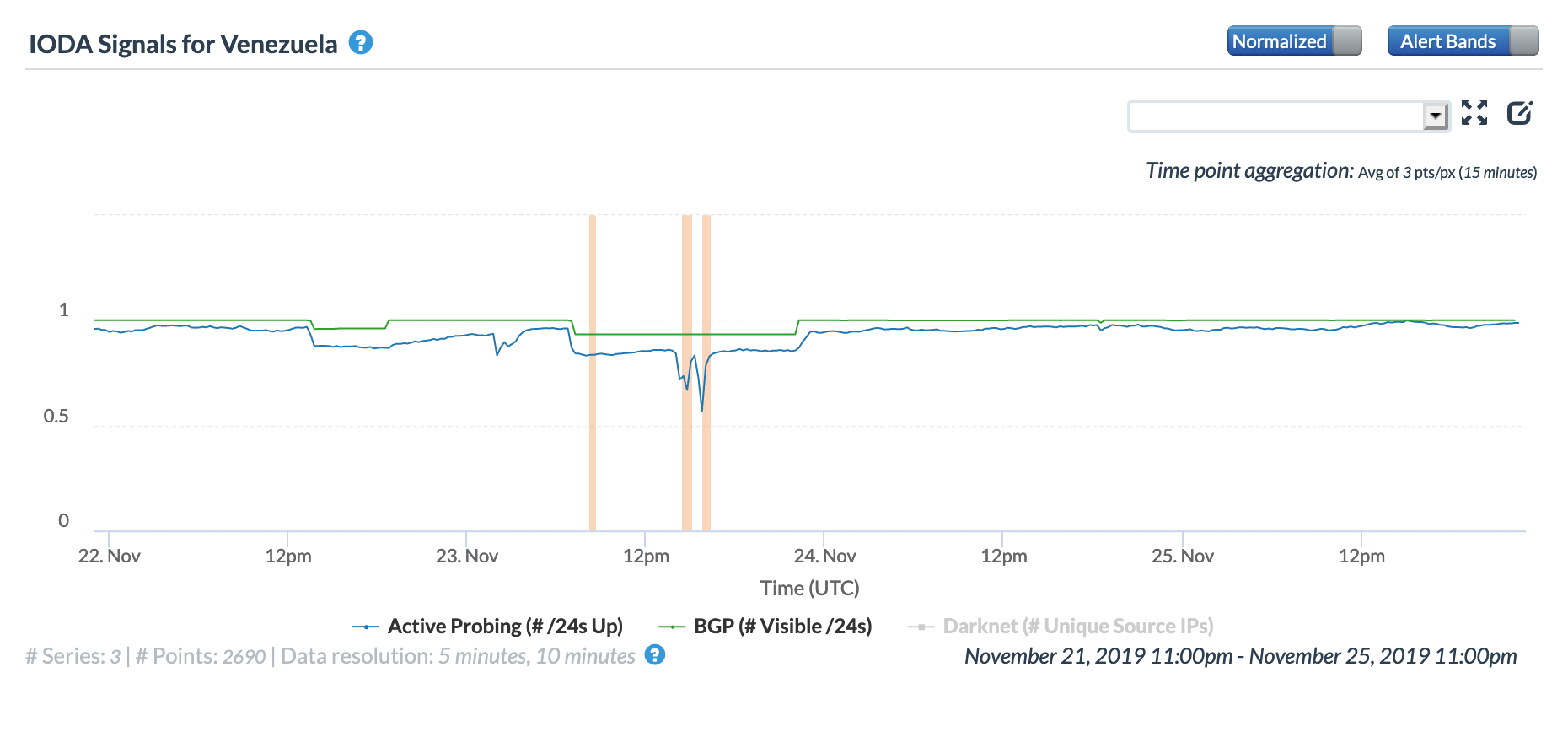

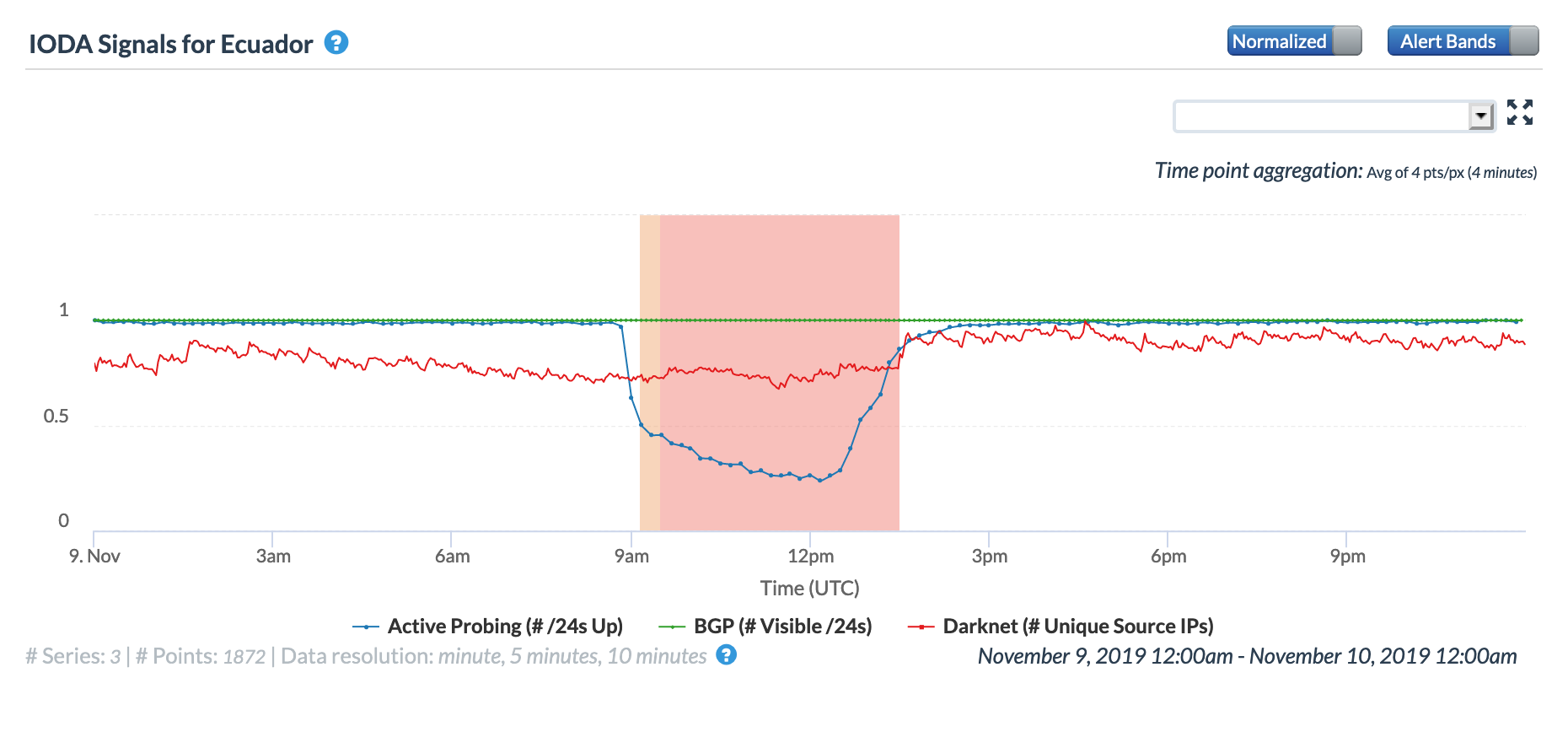

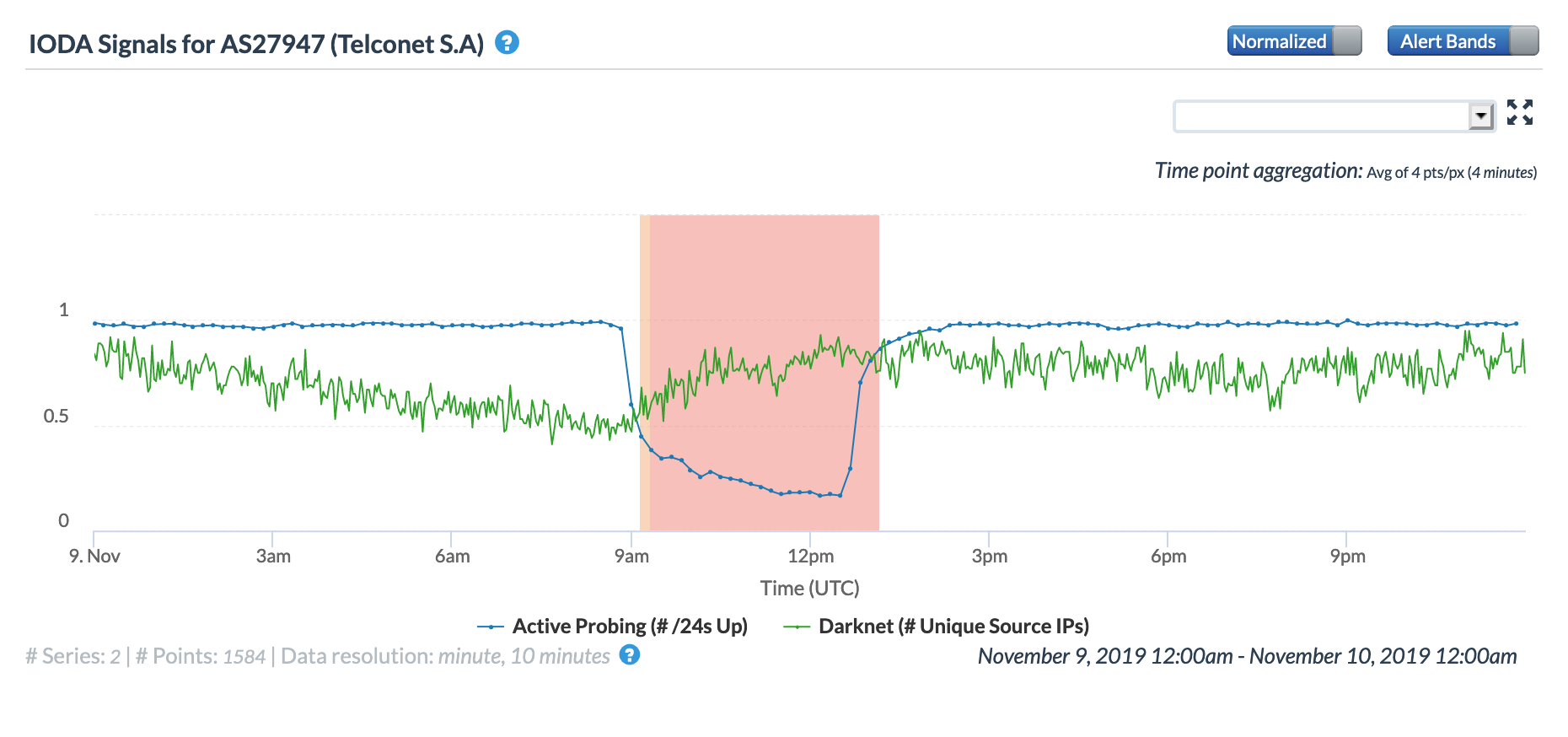

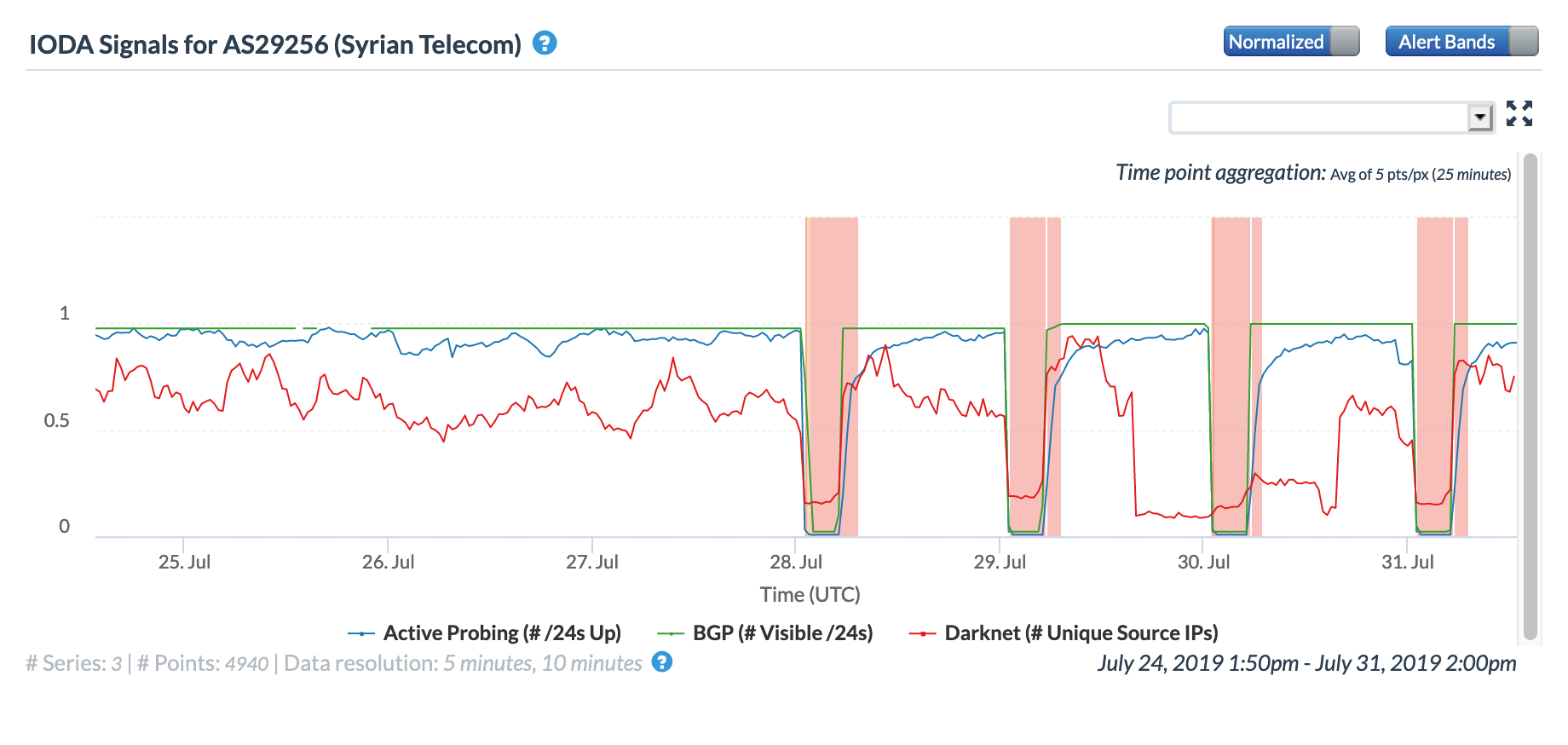

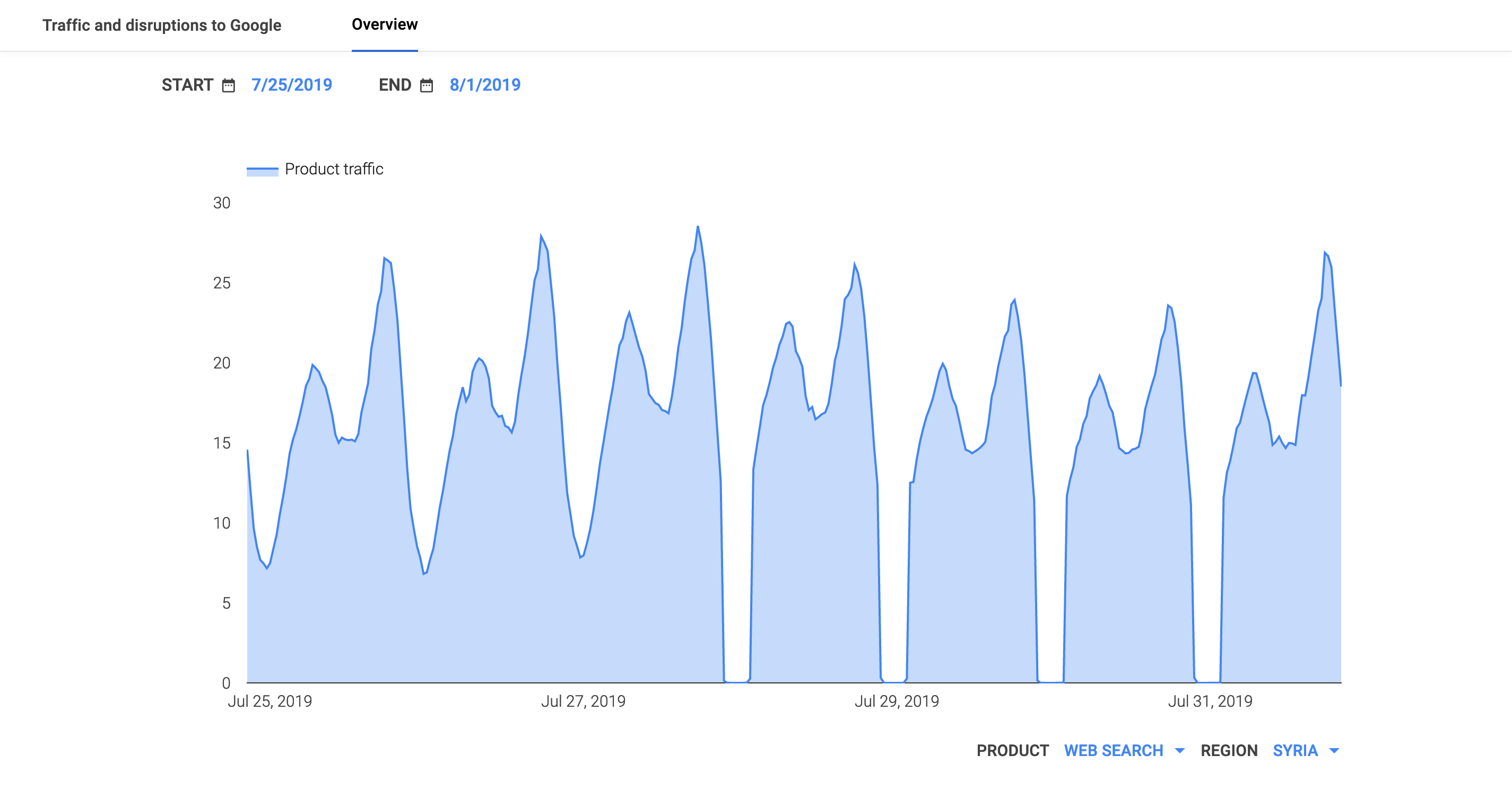

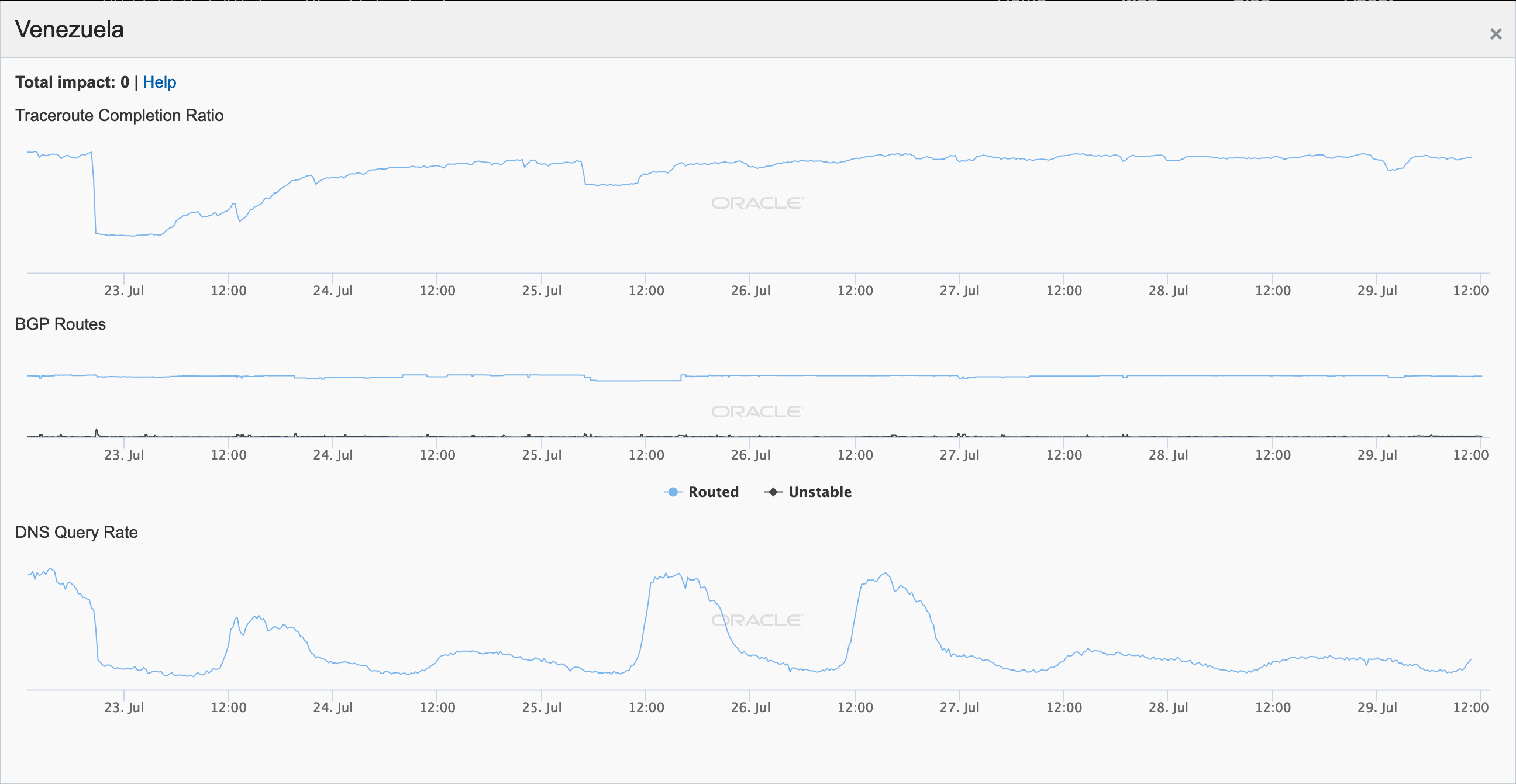

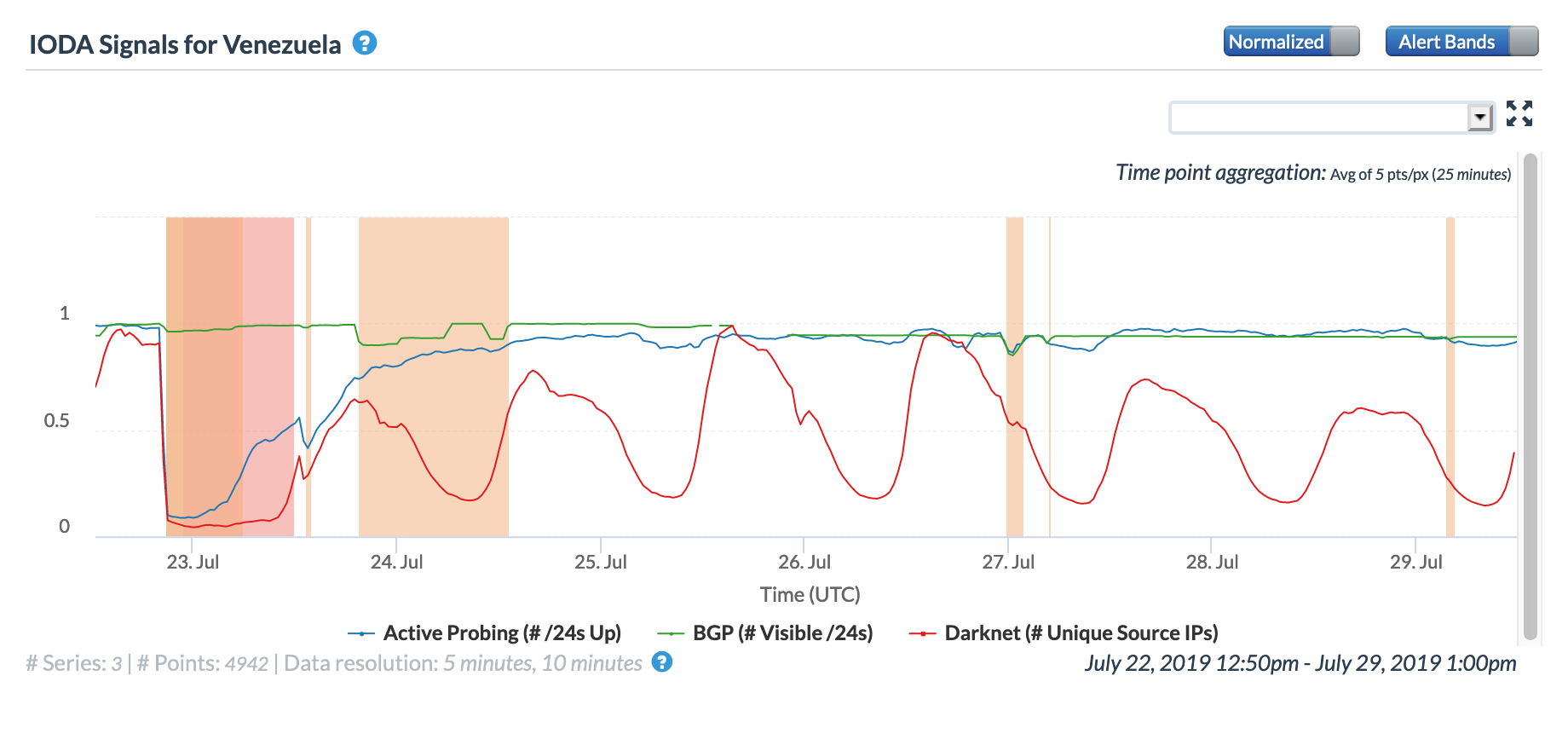

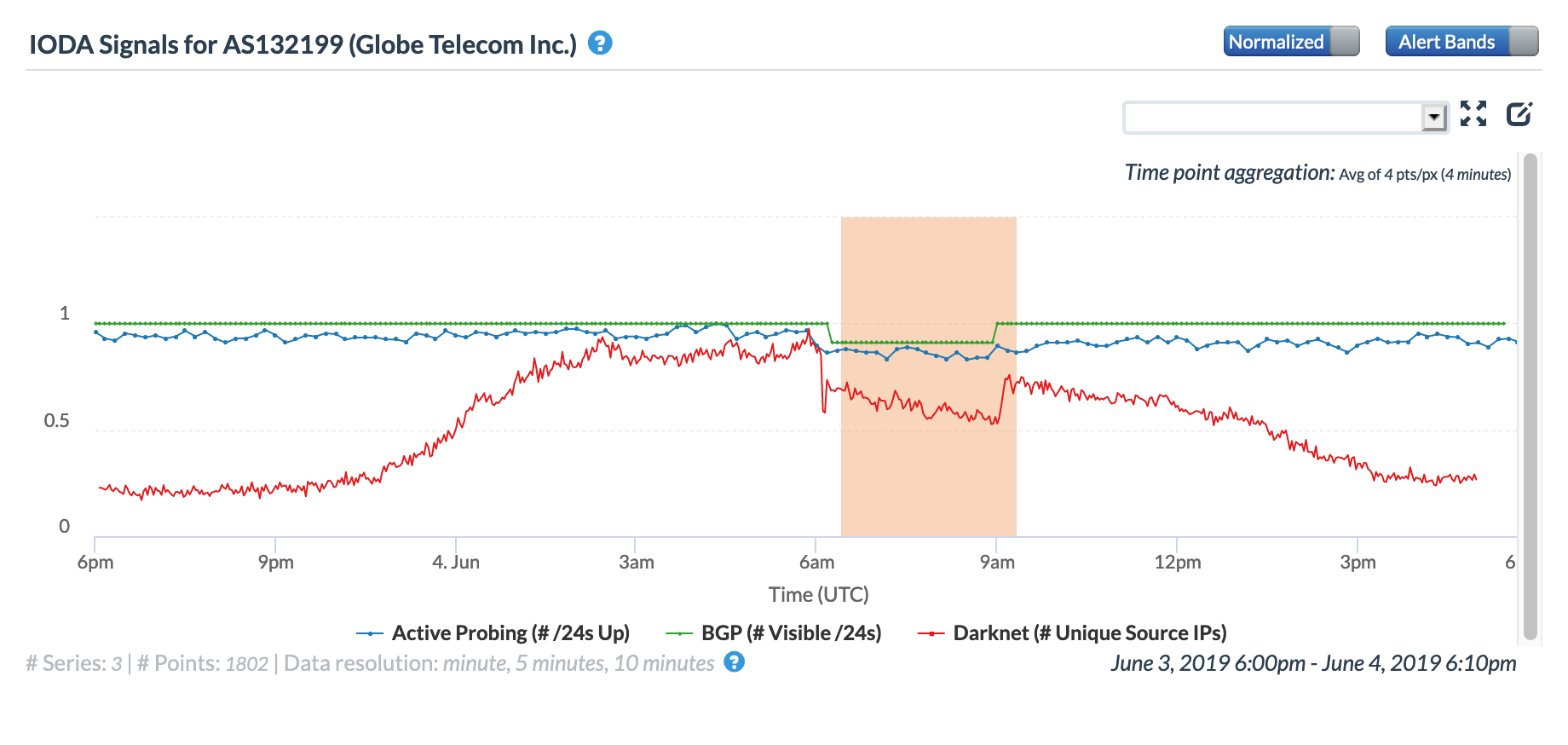

On May 5, a Tweet from Internet monitoring firm Netblocks confirmed that a power outage in Venezuela had disrupted Internet connectivity across multiple states within the country. Unfortunately, such power outages are a relatively common occurrence in Venezuela, and frequently impact Internet connectivity across the country. The Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA country-level graphs below show that the primary impact was to the active probing and traffic metrics, but the BGP metric also saw a brief nominal drop. The aggregated state-level CAIDA graph below illustrates the impact on active probing measurements to endpoints within the listed Venezuelan states – a multi-hour Internet disruption was measured in each of them.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Venezuela, May 5

CAIDA IODA graph for Venezuela, May 5

CAIDA IODA graph for multiple Venezuelan states, May 5

Weather

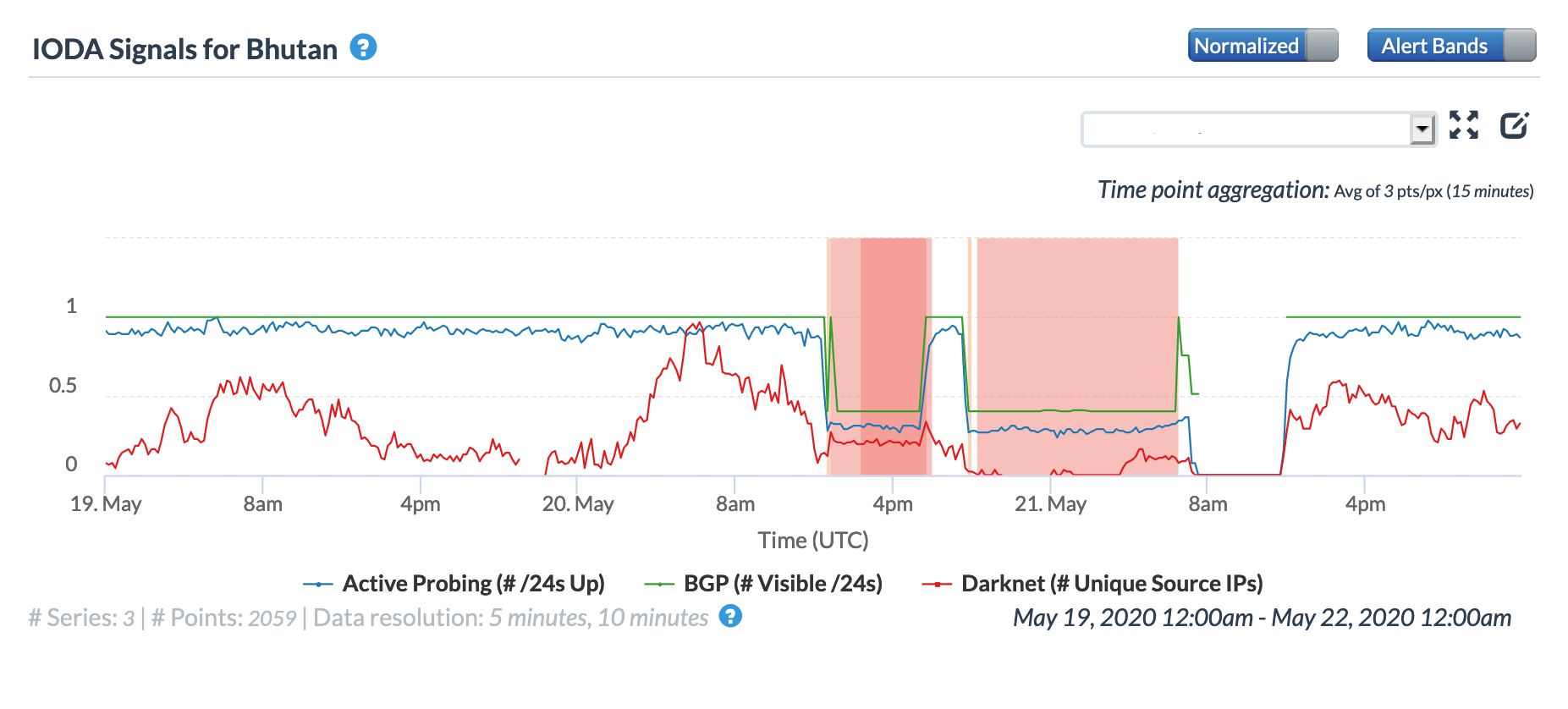

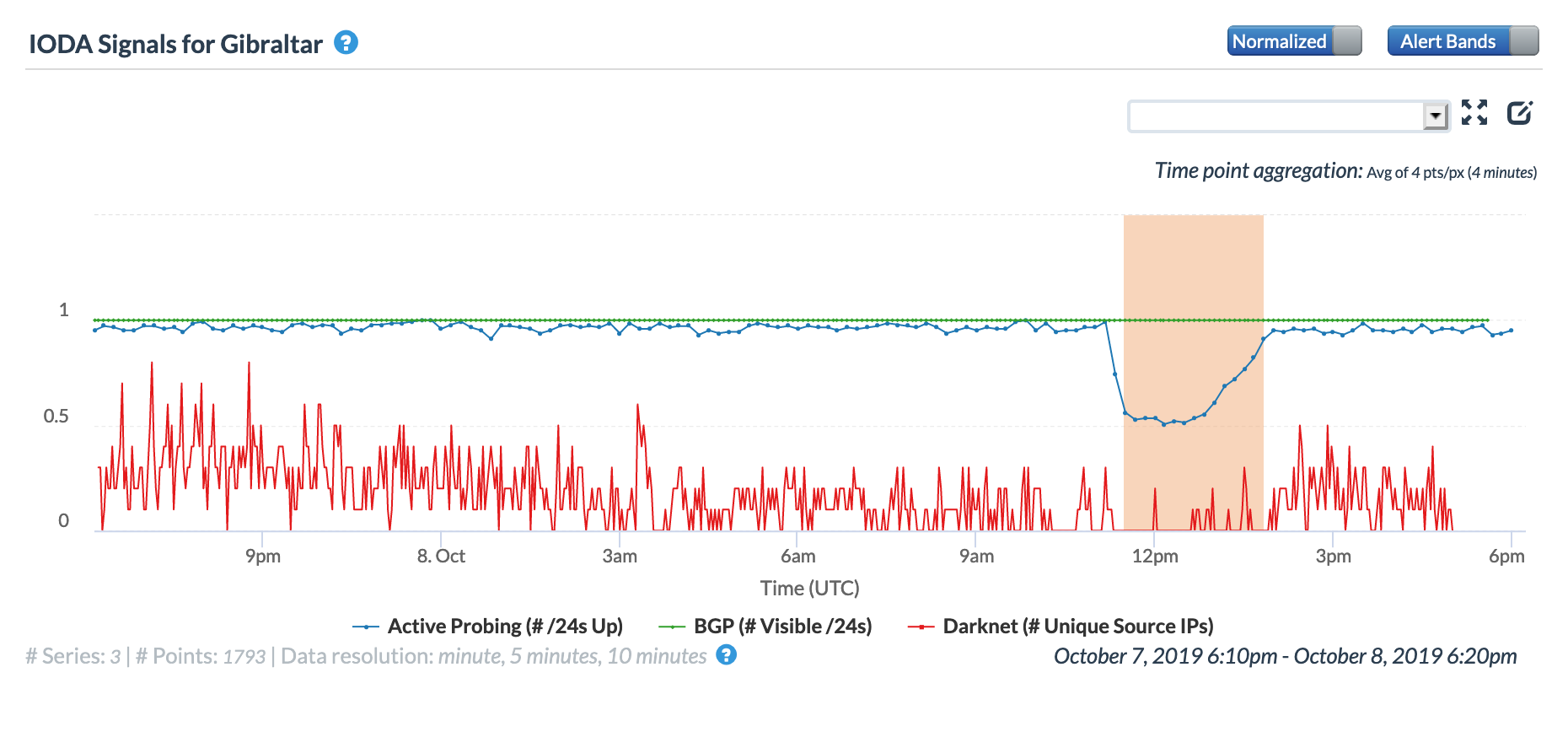

Internet connectivity was disrupted in Bhutan on May 20 & 21 because of damage to Bhutan Telecom infrastructure caused by Cyclone Amphan. As shown in both the Oracle and CAIDA graphs below, the disruption began around 12:00 GMT on May 20 and lasted for approximately 24 hours, though a brief restoration of connectivity occurred between 17:40-19:40 GMT. The infrastructure damage did not cause a complete country-wide outage, but the graphs show that all three measured metrics were impacted.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Bhutan, May 20-21

CAIDA IODA graph for Bhutan, May 20-21

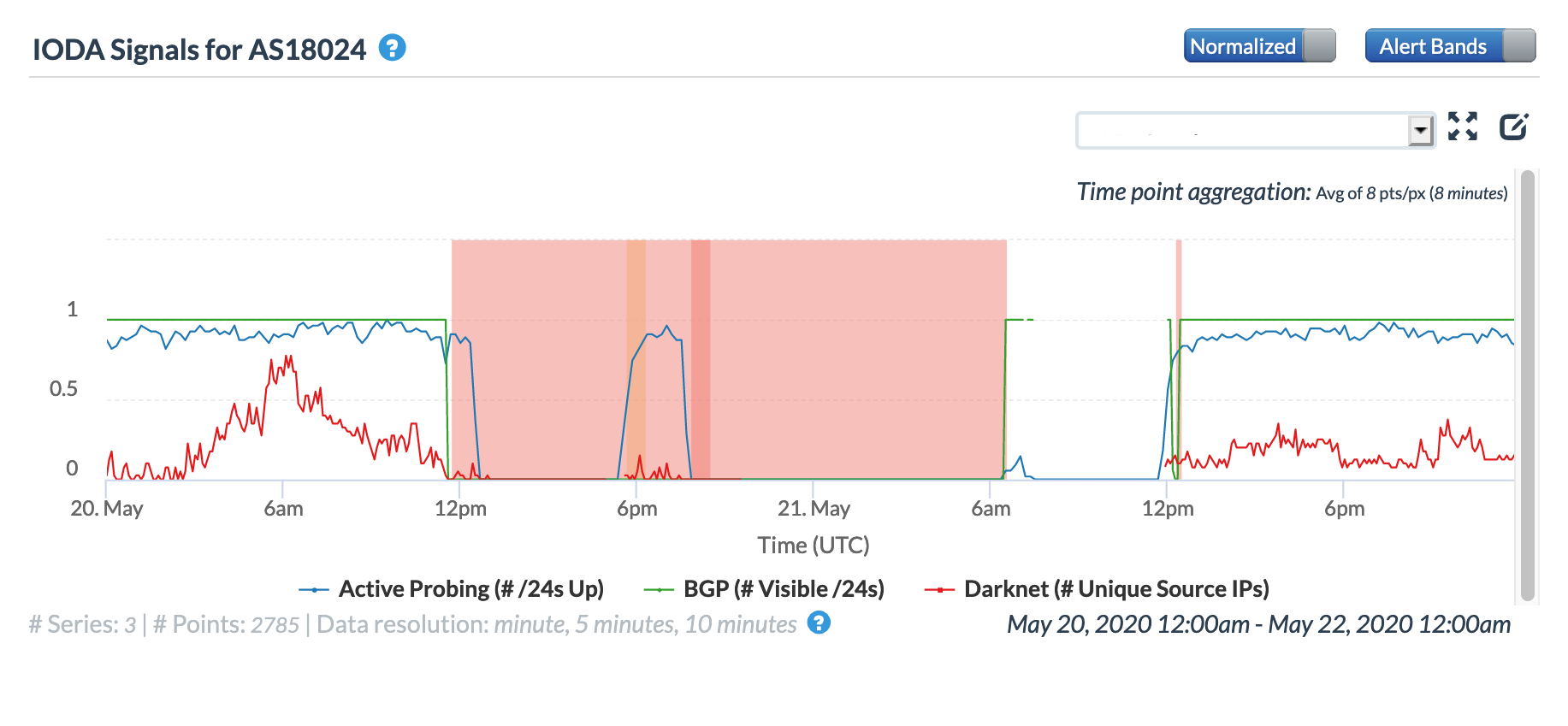

The impact was more significant, however, at a network level. The CAIDA graphs below for AS18024 (Bhutan Telecom) and AS17660 (DrukNet/Bhutan Telecom) show complete outages for all three measured metrics.

CAIDA IODA graph for AS18024 (Bhutan Telecom), May 20-21

CAIDA IODA graph for AS17660 (DrukNet/Bhutan Telecom), May 20-21

Fiber/Cable Cut

Fiber optic cables cut by vandals disrupted Internet connectivity for tens of thousands of users in France on May 5 & 6. The cables that were damaged impacted connectivity for both home and business subscribers, as well as cloud provider Scaleway. The Oracle graphs below show the impact on traceroute measurements to endpoints within three French network providers. In each case, traceroutes through the network’s primary upstream provider drop to near zero, but begin reaching the target network through an alternate upstream almost immediately. Nominal increases in latency are also evident, but for these network providers, redundant connectivity meant that the overall impact was nominal.

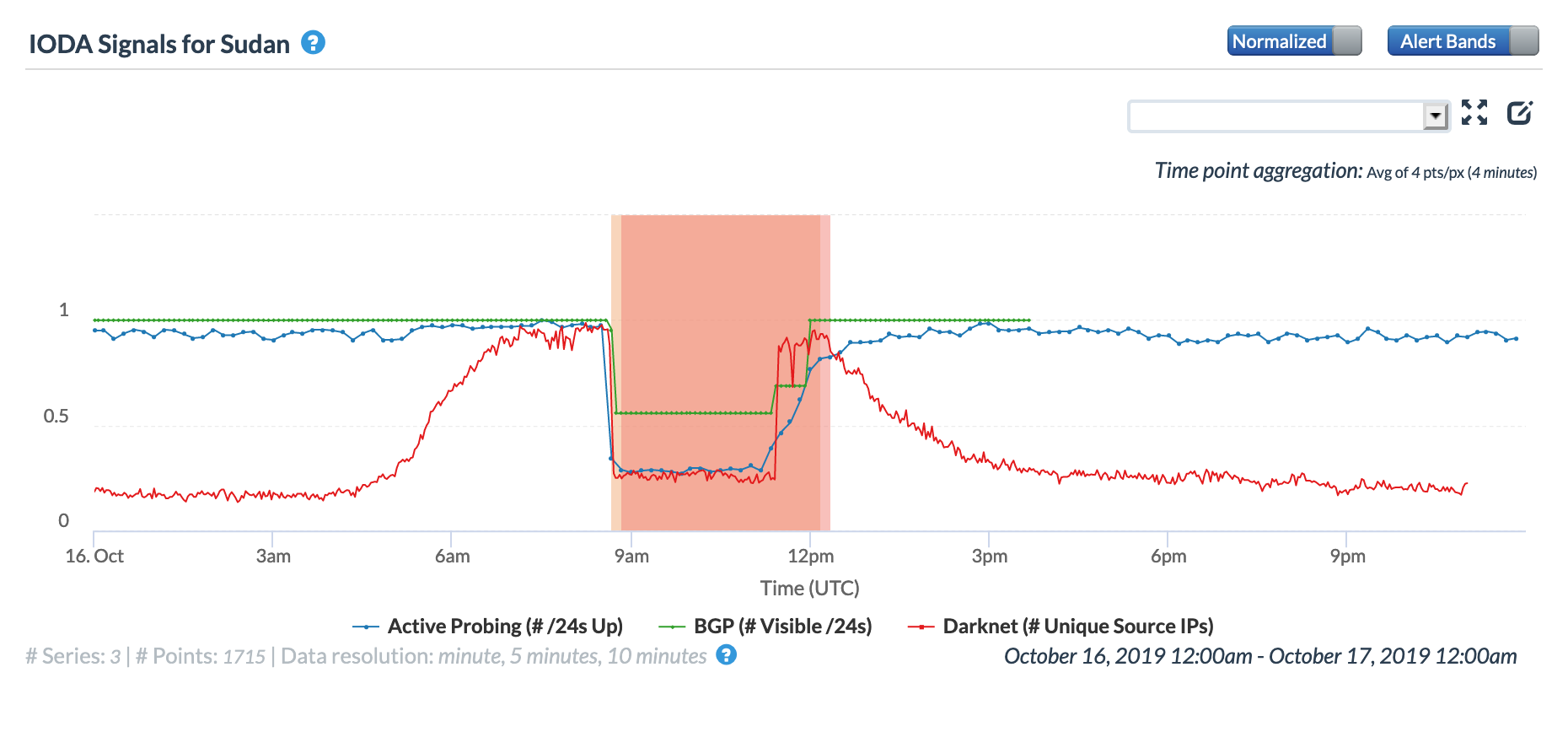

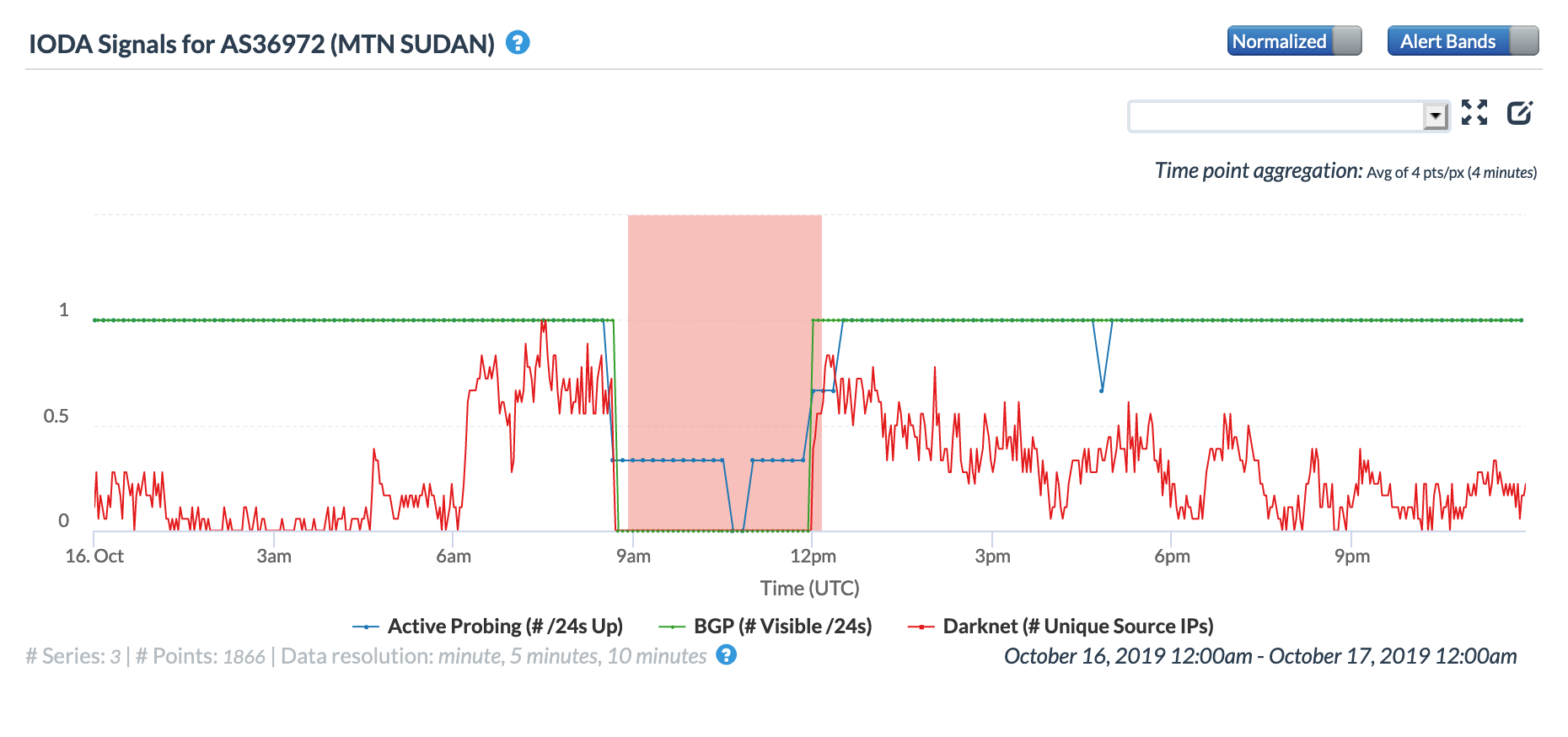

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS2094 (Renater), May 5-6

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS31178 (Celeonet SAS), May 5-6

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS34949 (IDLINE SAS), May 5-6

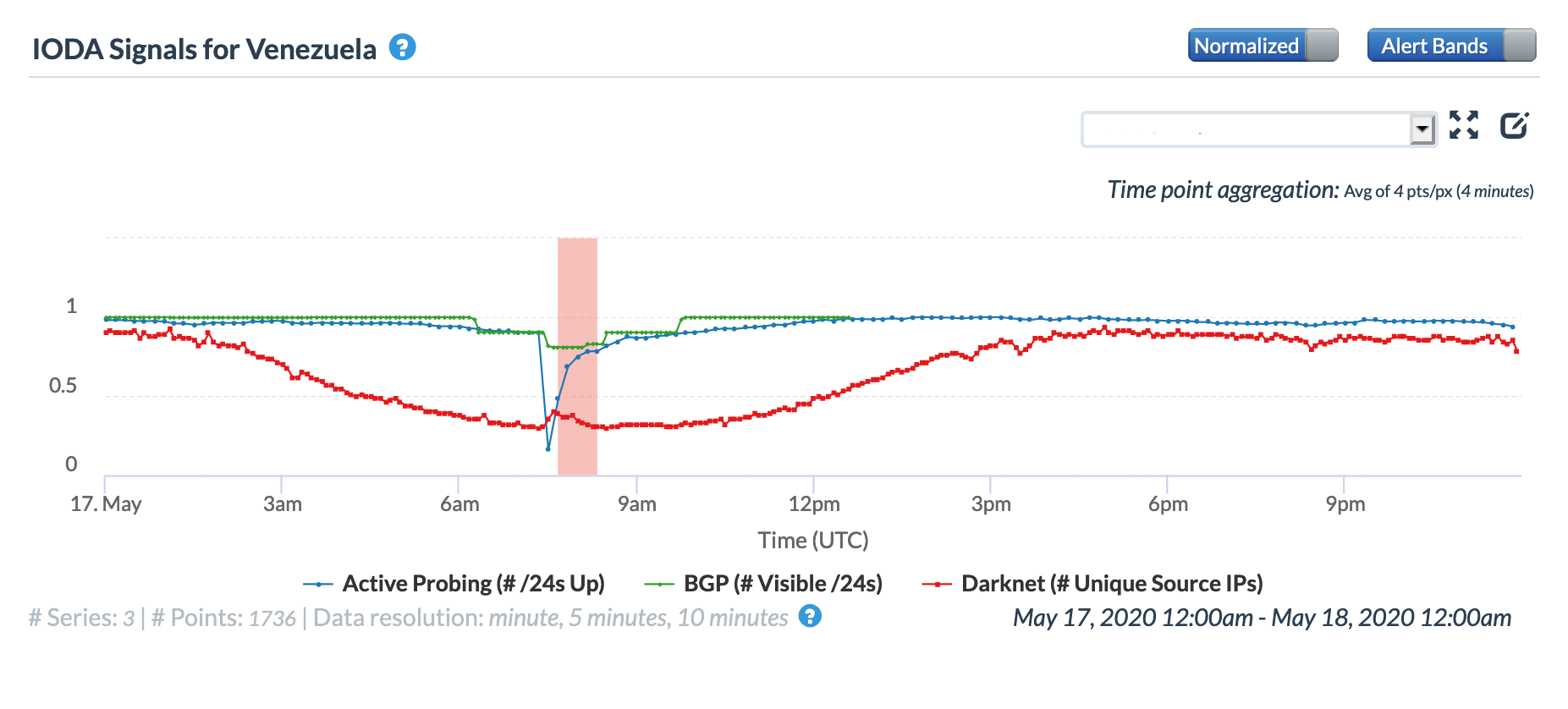

According to a Twitter thread from Venezuelan journalist Fran Monroy Moret, repairs to a submarine cable resulted in a multi-hour Internet disruption across multiple network providers in Venezuela on May 17. Multiple submarine cables land in Venezuela, but the thread does not mention which cable was being repaired. However, references to CenturyLink within the thread could indicate that the cable in question is either the Americas-II or the South American Crossing (SAC), as CenturyLink is listed among the owners of both.

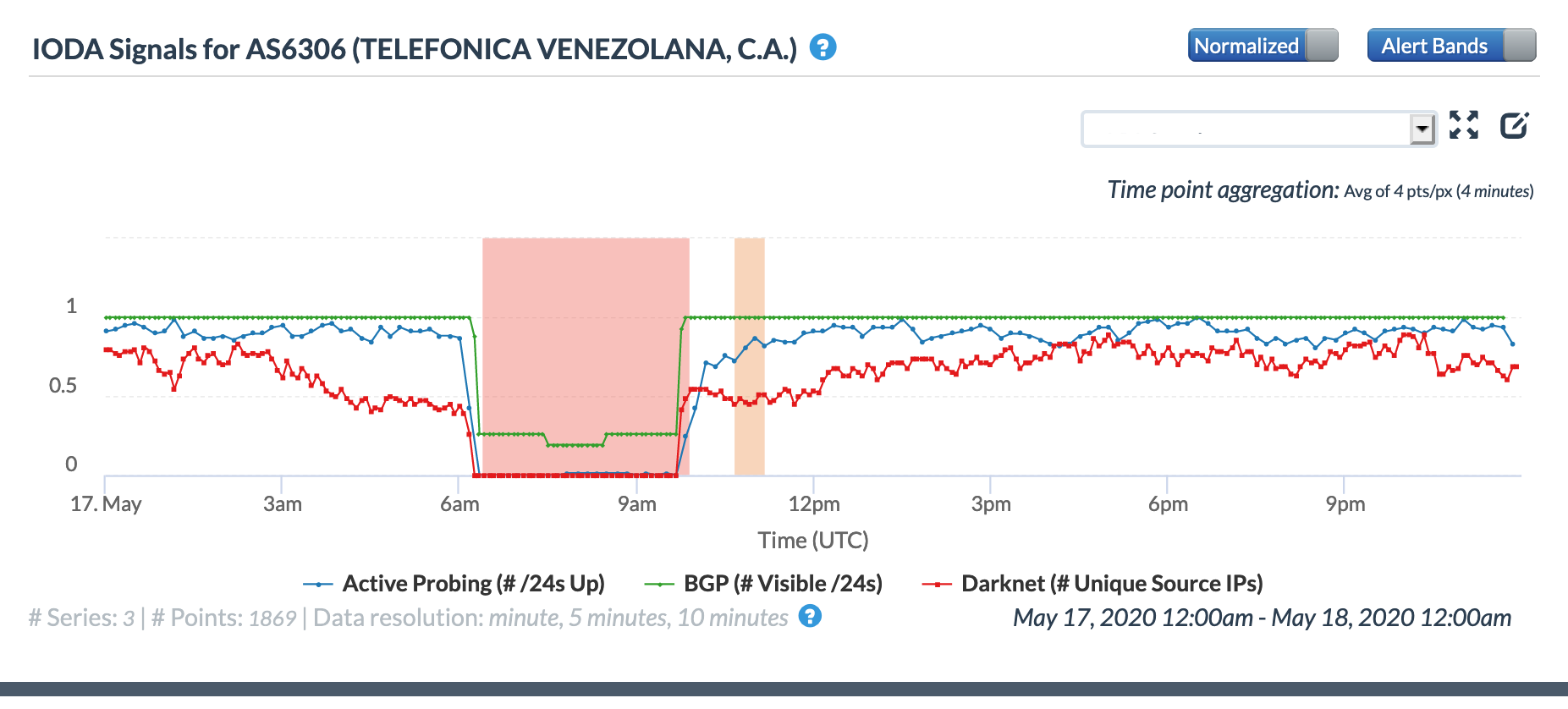

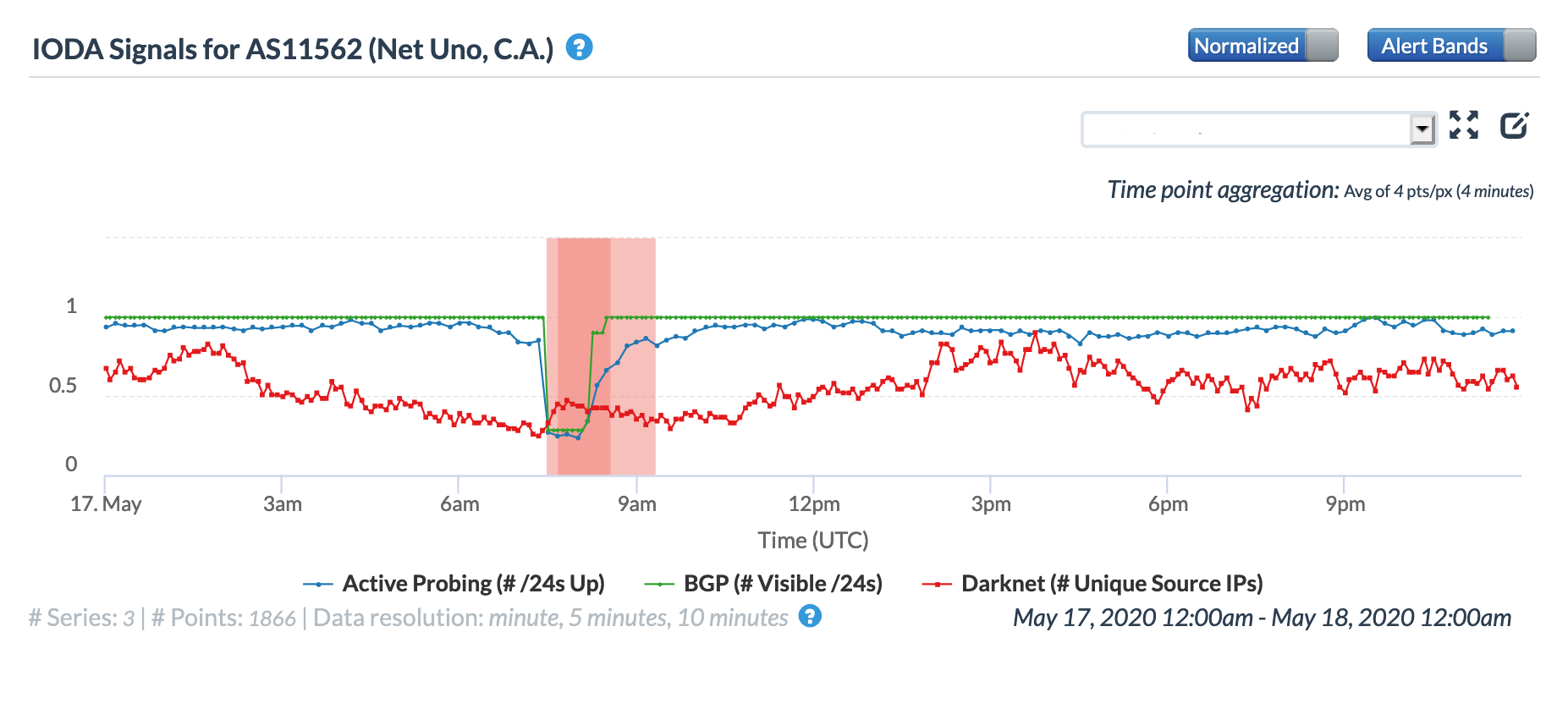

The Twitter thread suggested that the disruption would last eight hours, from 02:00 – 10:00 local time (06:00 – 14:00 GMT). At a country level, the eight hour-disruption is most evident in the BGP metric across both the Oracle and CAIDA graphs, as the impact to the active probing and traffic-related metrics appeared to be briefer in duration. Local network provider Movistar (AS6306) also experienced a disruption for the full repair duration, as shown in the graphs below. However, local providers Inter (AS21826) and Net Uno (AS11562) appeared to experience briefer disruptions, occurring in the middle of the repair period and primarily evident in the active probing and BGP metrics.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Venezuela, May 17

CAIDA IODA graph for Venezuela, May 17

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS6306 (Movistar), May 17

CAIDA IODA graph for AS6306 (Movistar), May 17

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS21826 (Inter), May 17

CAIDA IODA graph for AS21826 (Inter), May 17

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS11562 (Net Uno), May 17

CAIDA IODA graph for AS11562 (Net Uno), May 17

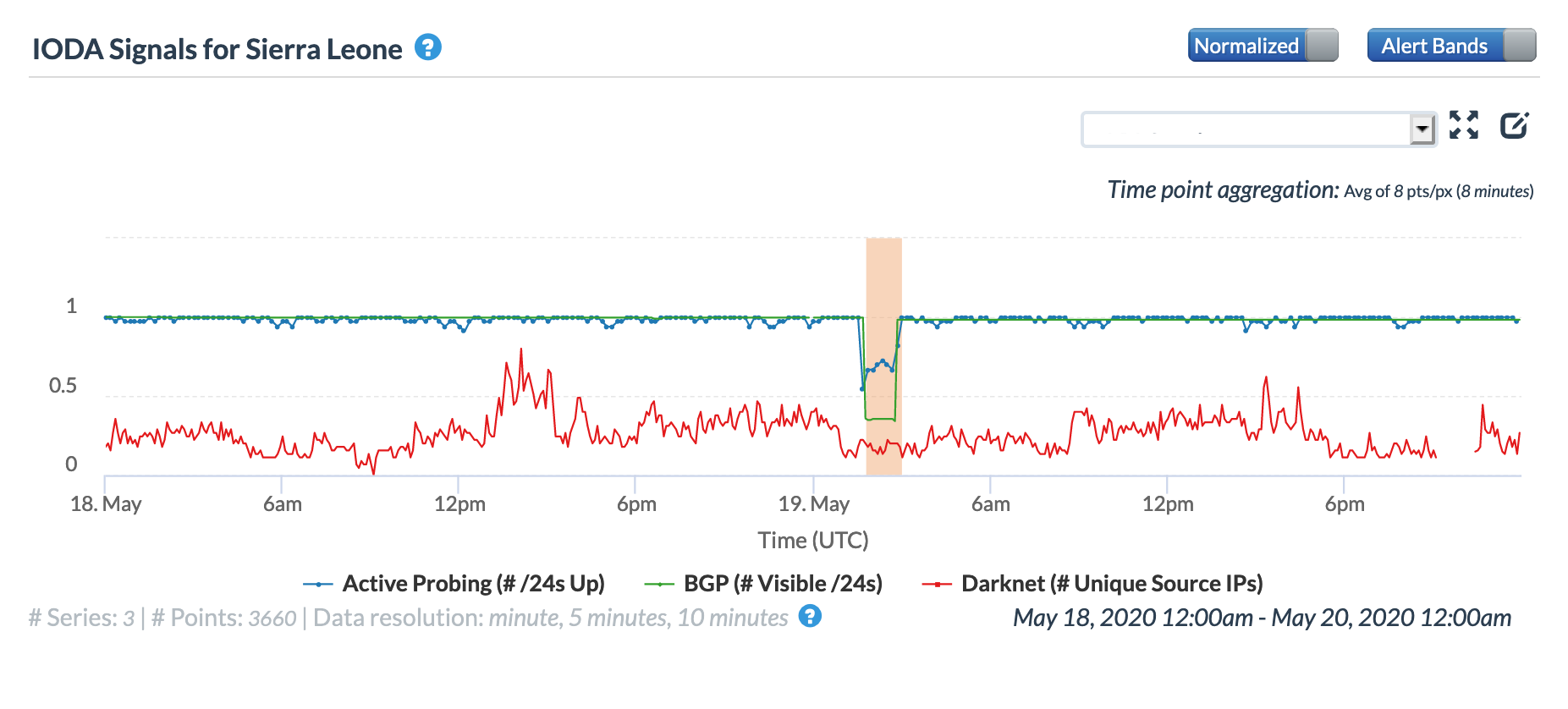

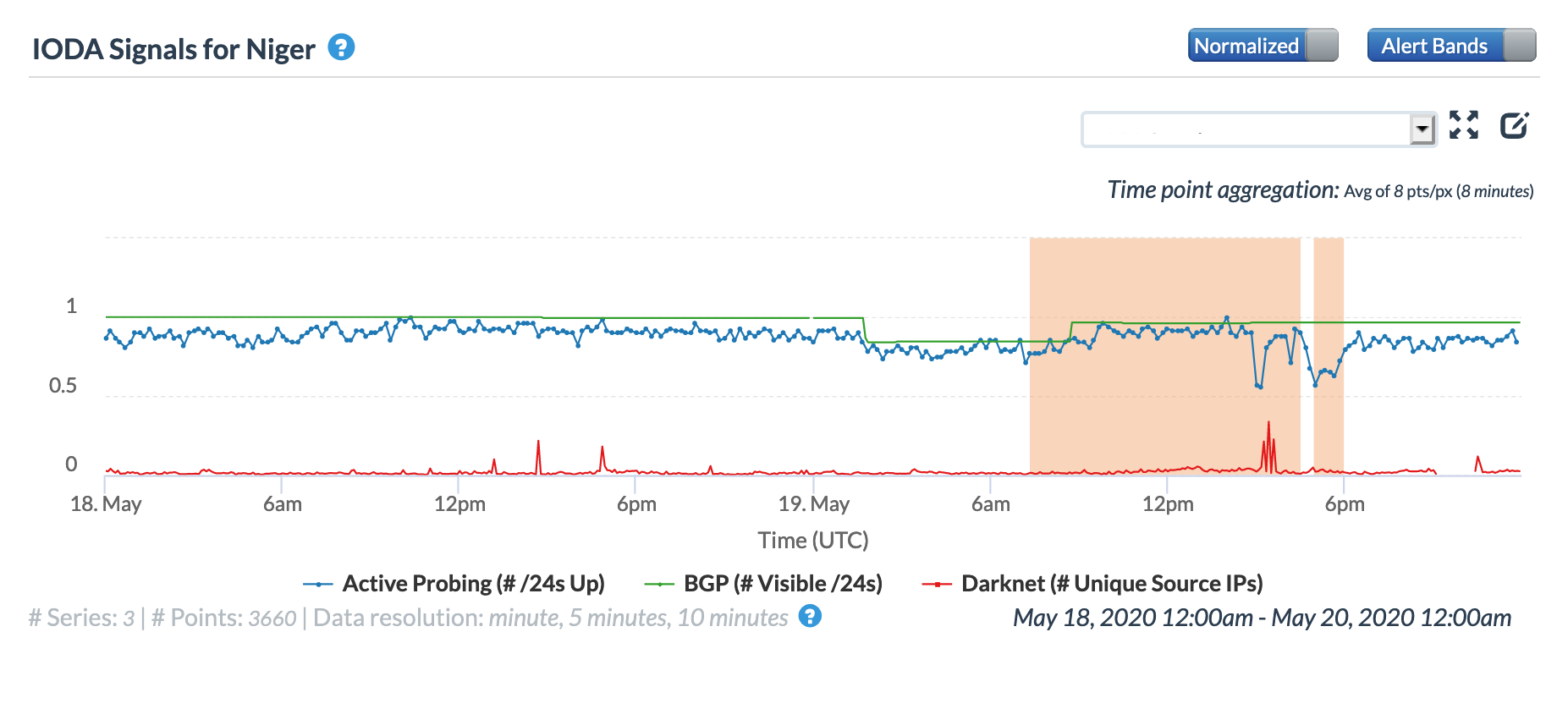

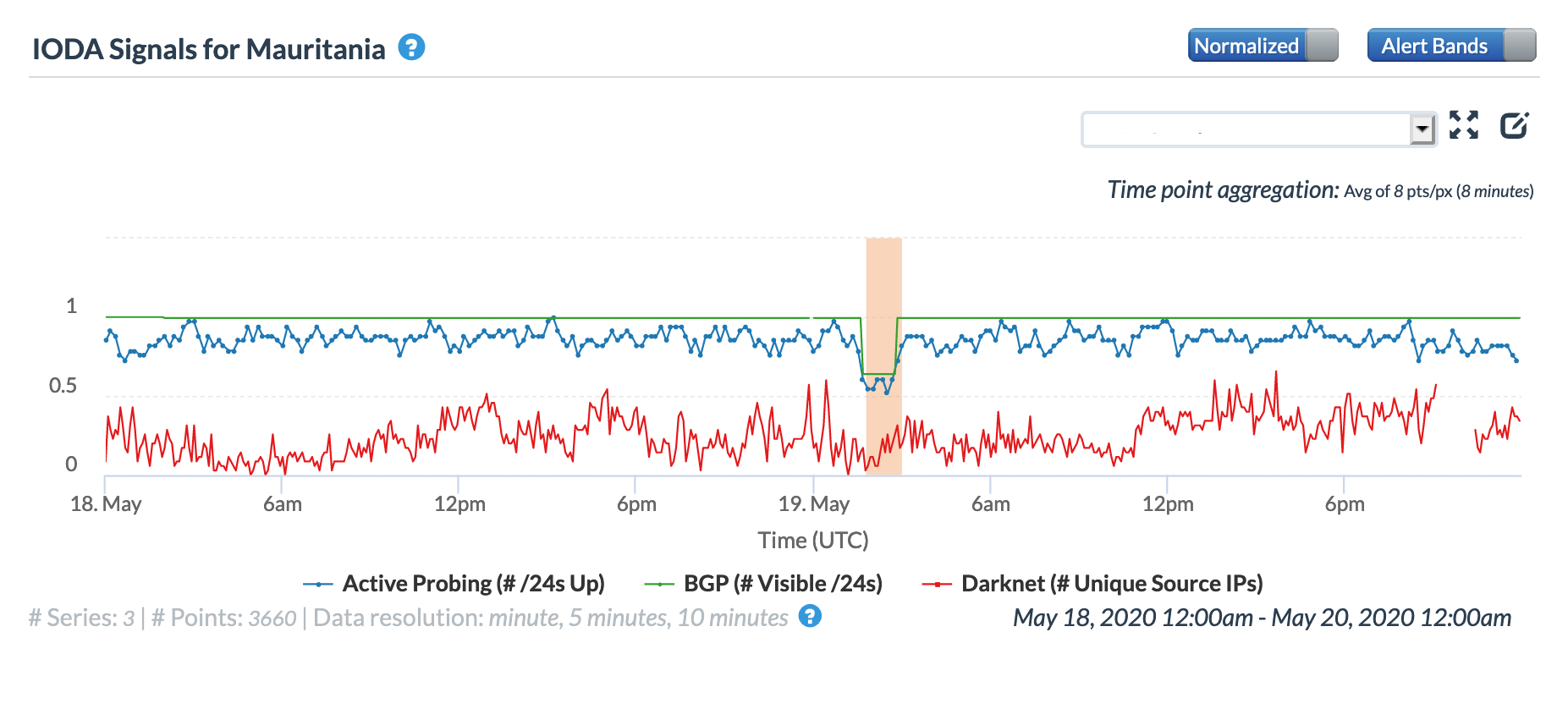

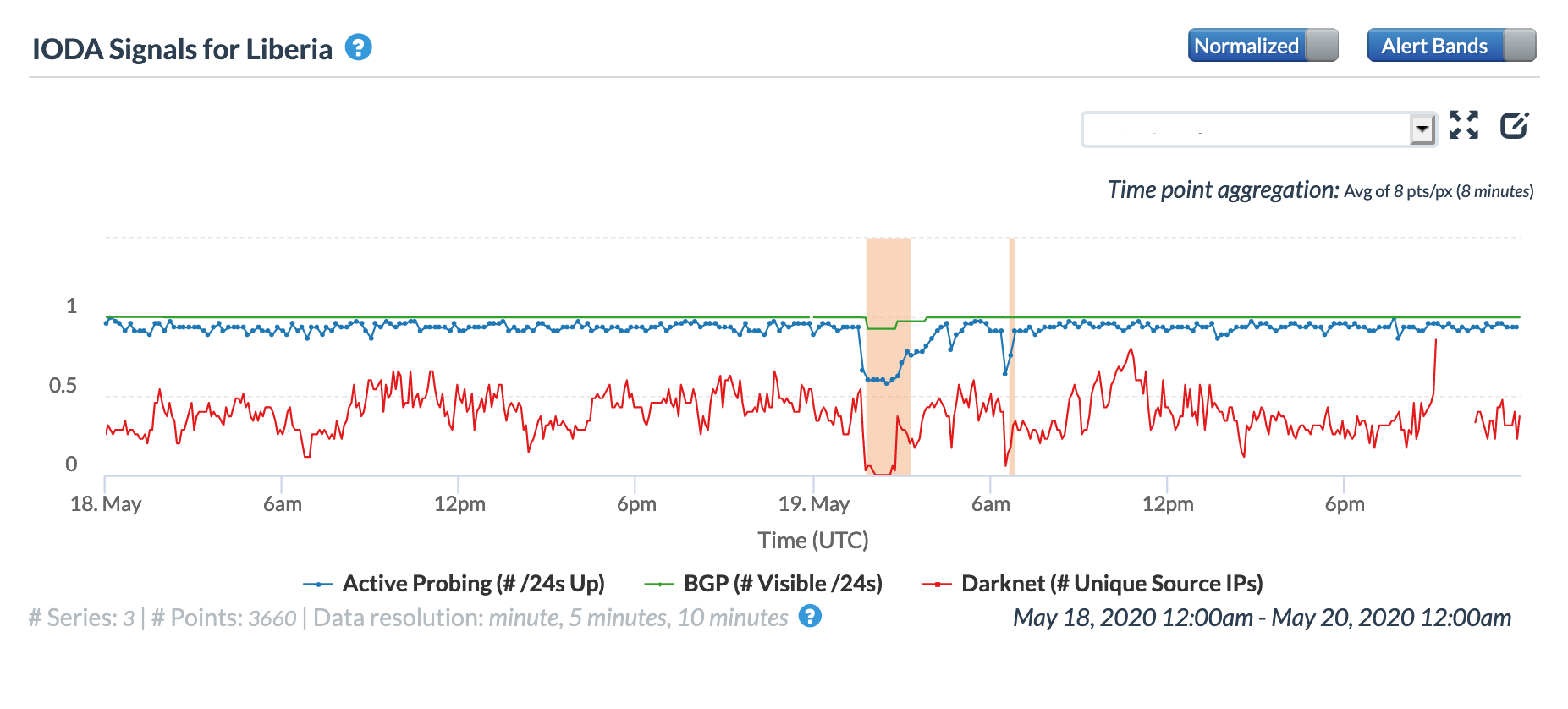

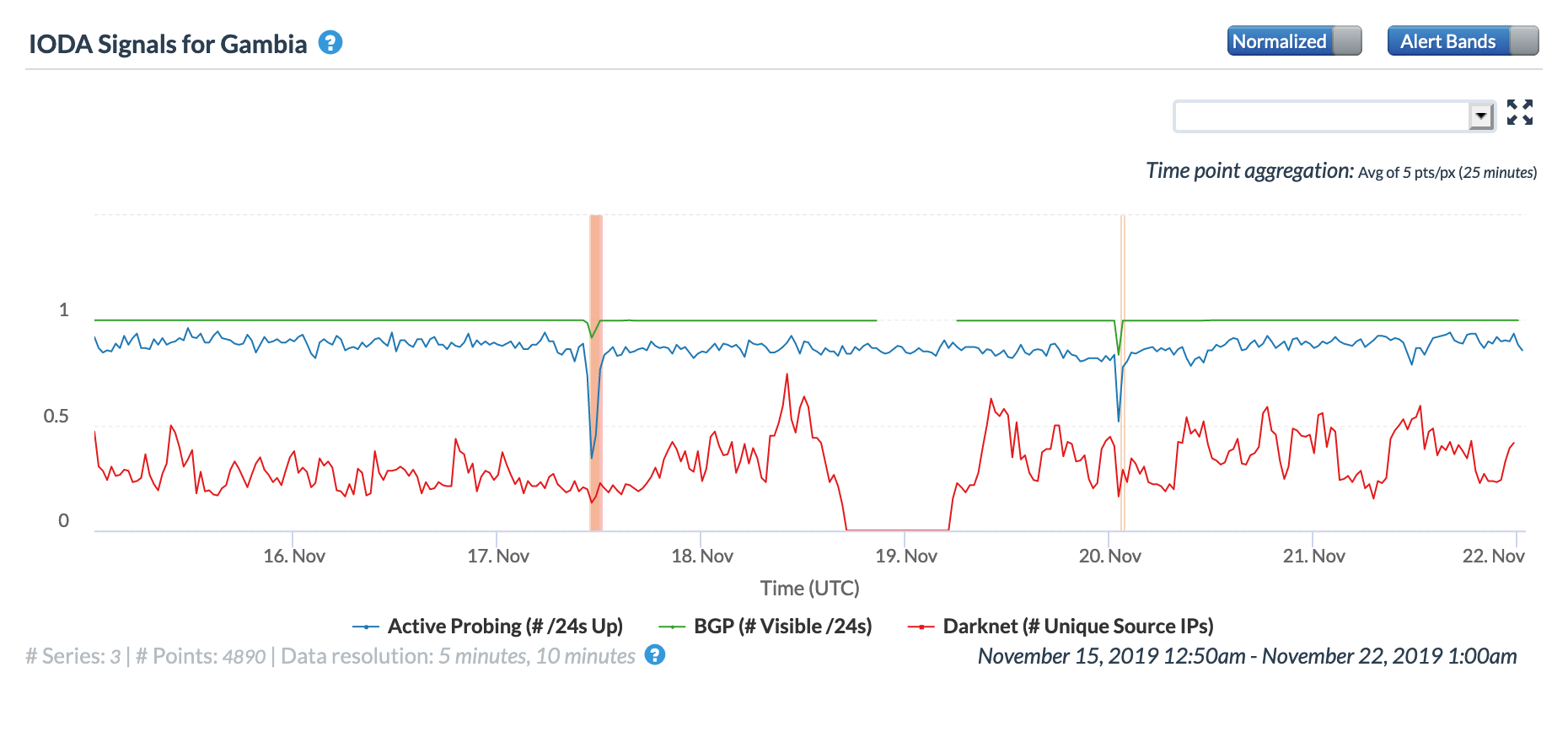

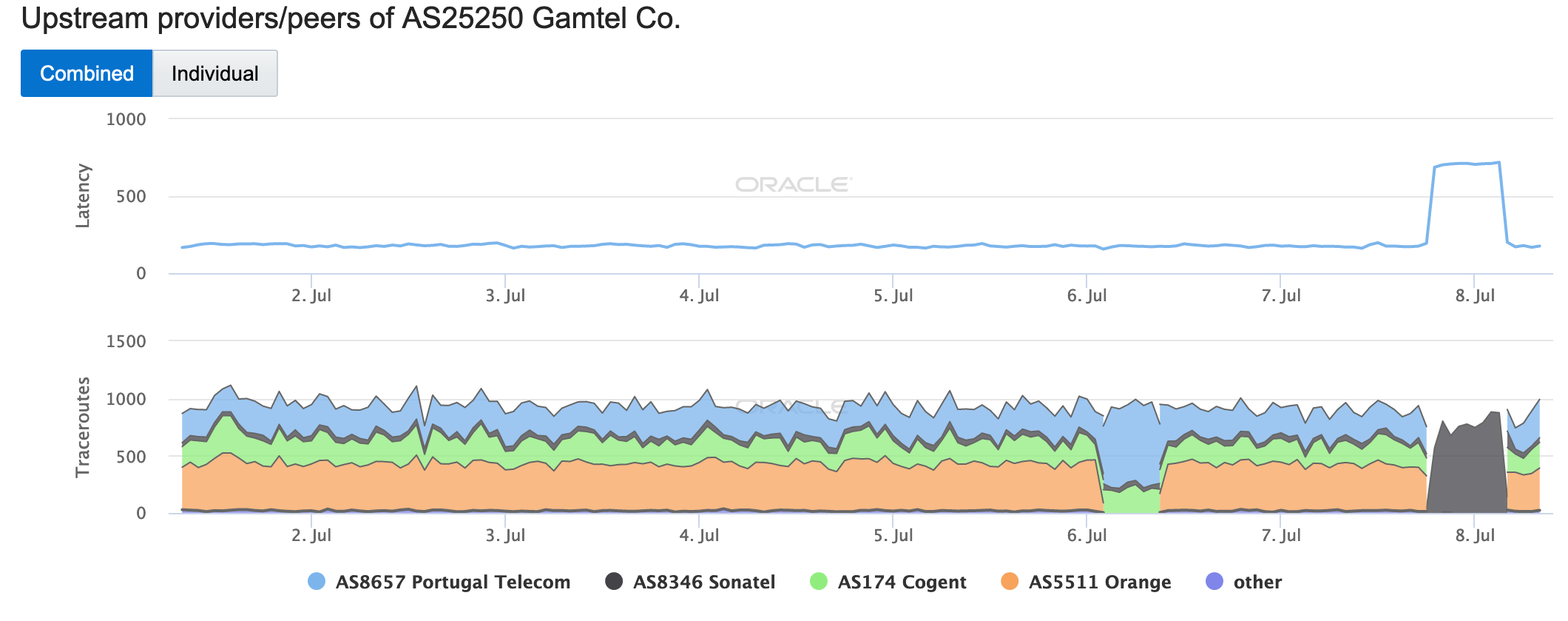

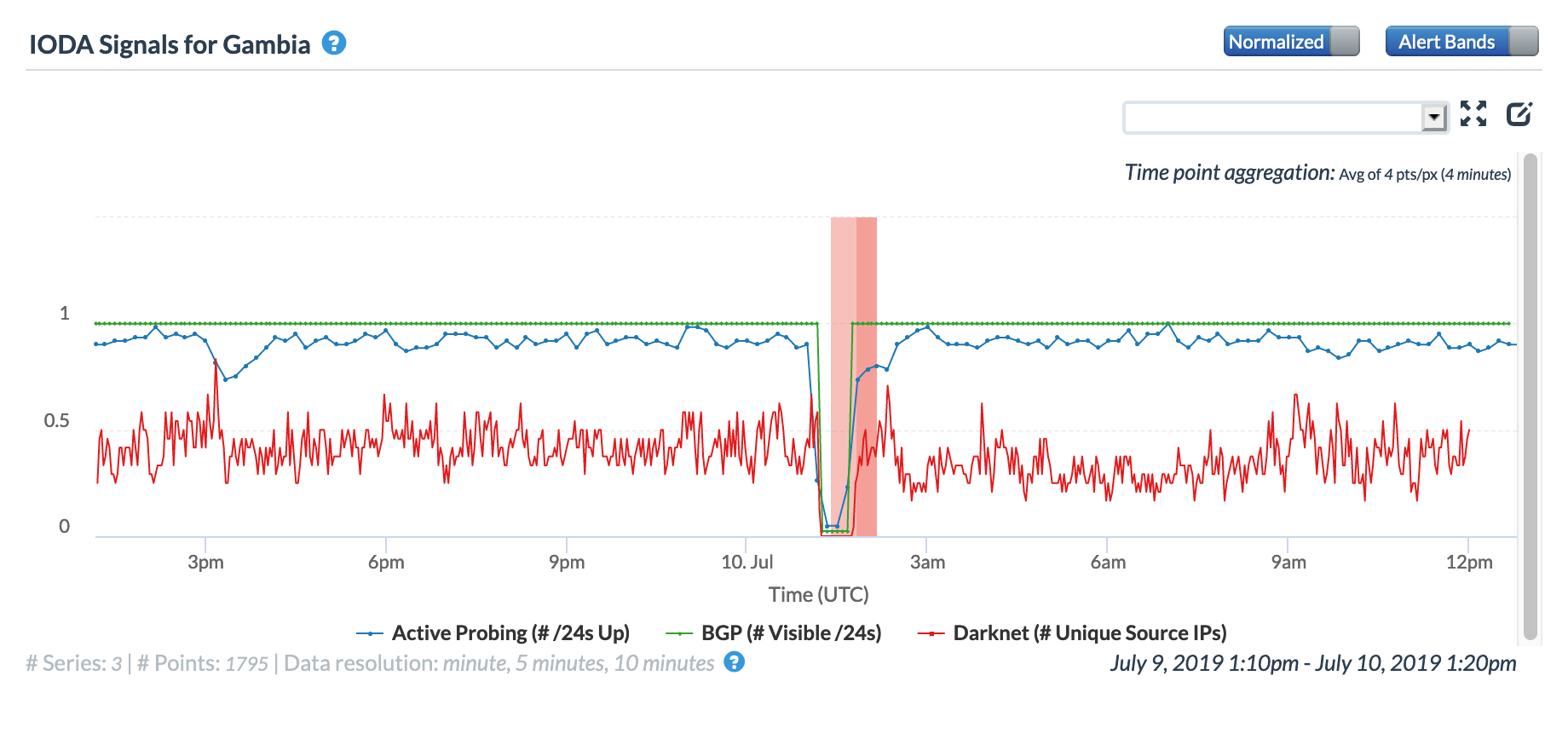

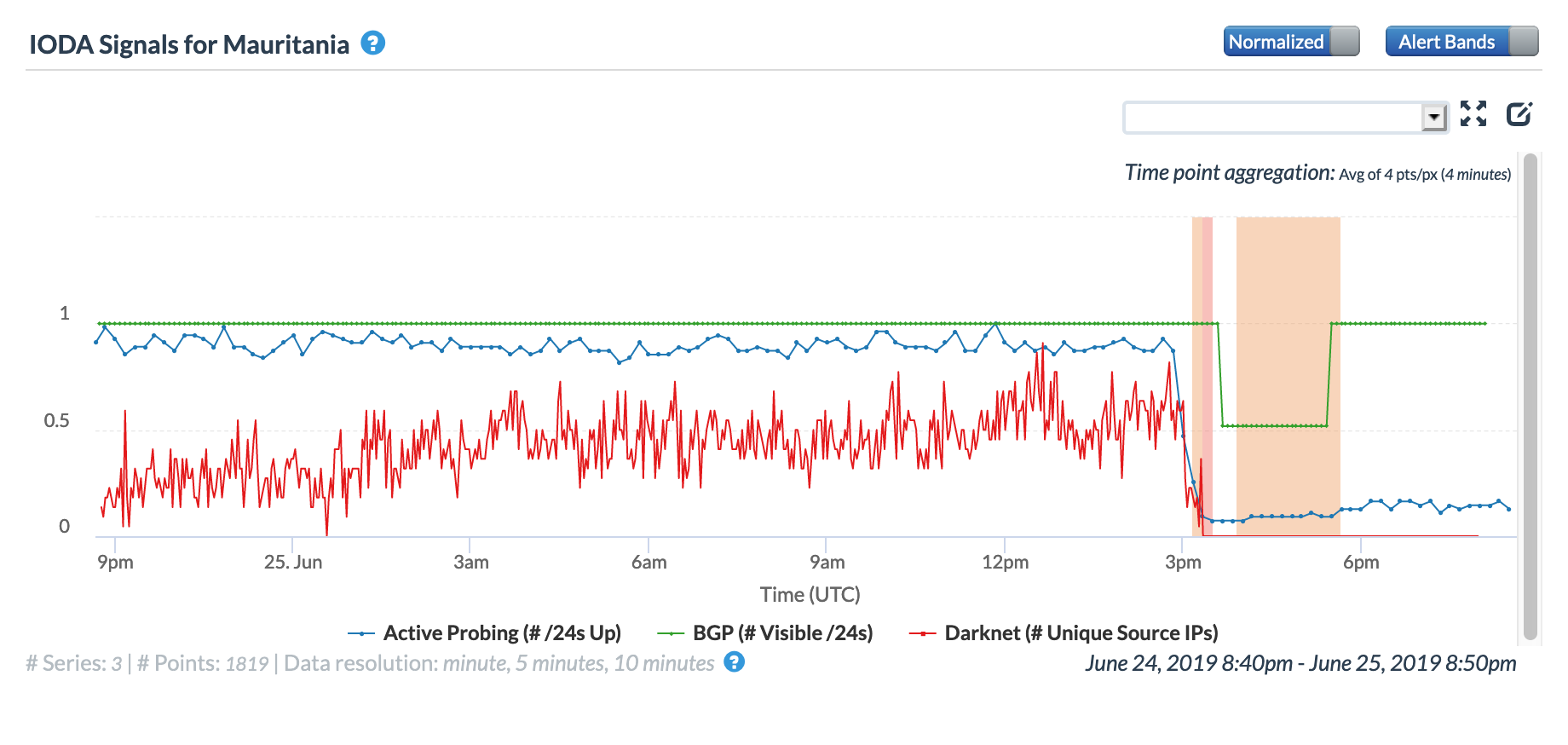

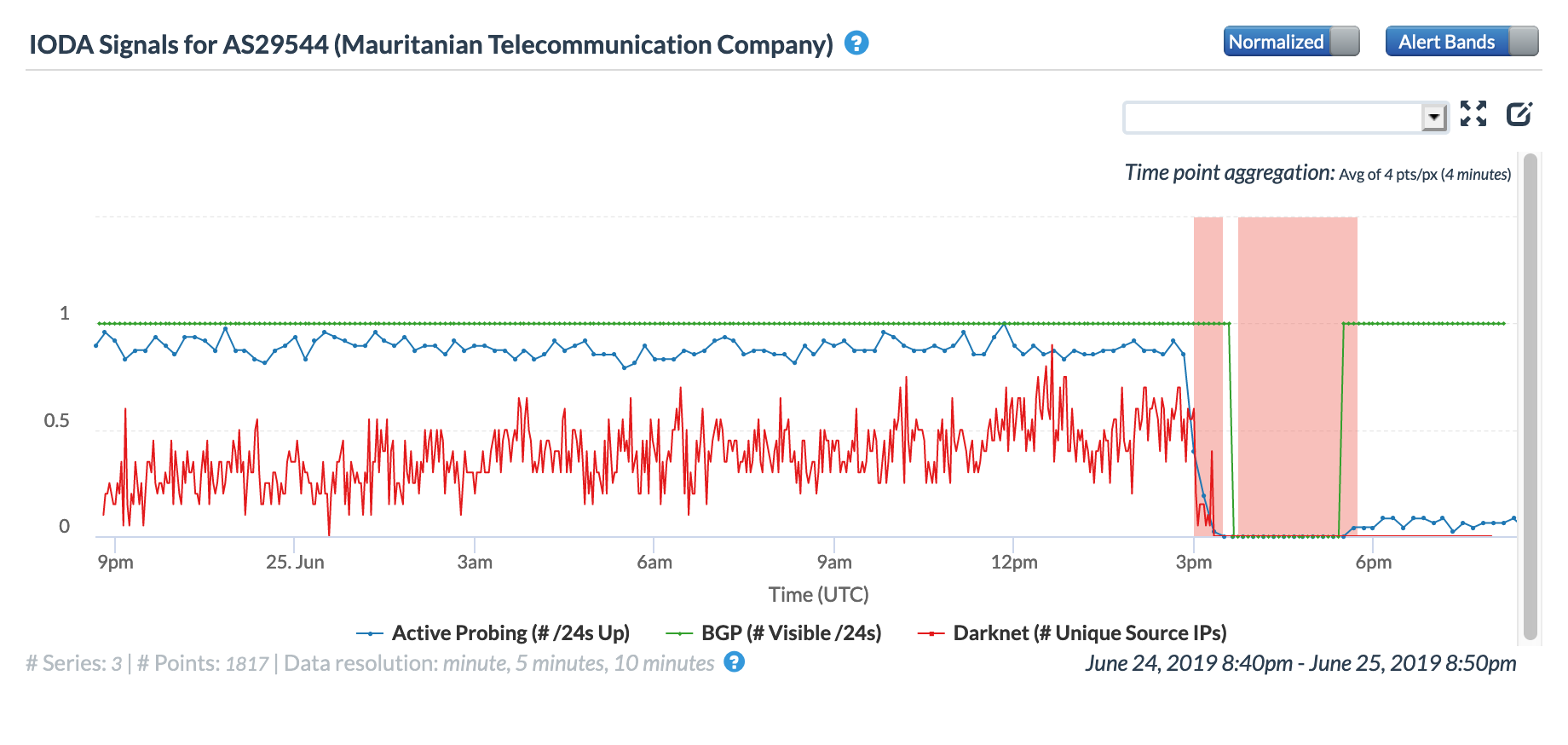

A May 19 Tweet from Oracle Internet Intelligence highlighted Internet disruptions detected across multiple countries, and an associated Tweet pointed to the ACE submarine cable as the likely culprit. Impacted countries included Sierra Leone, Niger, Mauritania, Liberia, and the Gambia. The graphs below show that the disruptions began around 01:30 GMT, lasting approximately 90 minutes, although the impacts linger for several additional hours in Niger’s graphs.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Sierra Leone, May 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Sierra Leone, May 19

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Niger, May 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Niger, May 19

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Mauritania, May 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Mauritania, May 19

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Liberia, May 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Liberia, May 19

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for the Gambia, May 19

CAIDA IODA graph for the Gambia, May 19

On May 27, a brief Internet disruption was detected on French Polynesia starting just after 12:00 GMT and lasting for about an hour, as shown in the graphs below. The active probing, BGP, and traffic metrics were impacted across both Oracle and CAIDA measurements. The Honotua submarine cable is the island nation’s primary international Internet connection, connecting it to Hawaii, and it is likely that problems with this cable were the cause of the observed disruption. The network-level graphs below all show AS36149 (Hawaiian Telecom Services Company) as an upstream provider, and a drop was seen in the number of successful traceroutes across this network in all three graphs.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for French Polynesia, May 27

CAIDA IODA graph for French Polynesia, May 27

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS56017 (Vitu), May 27

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS9471 (Onati), May 27

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS55943 (Onati), May 27

Network Issues

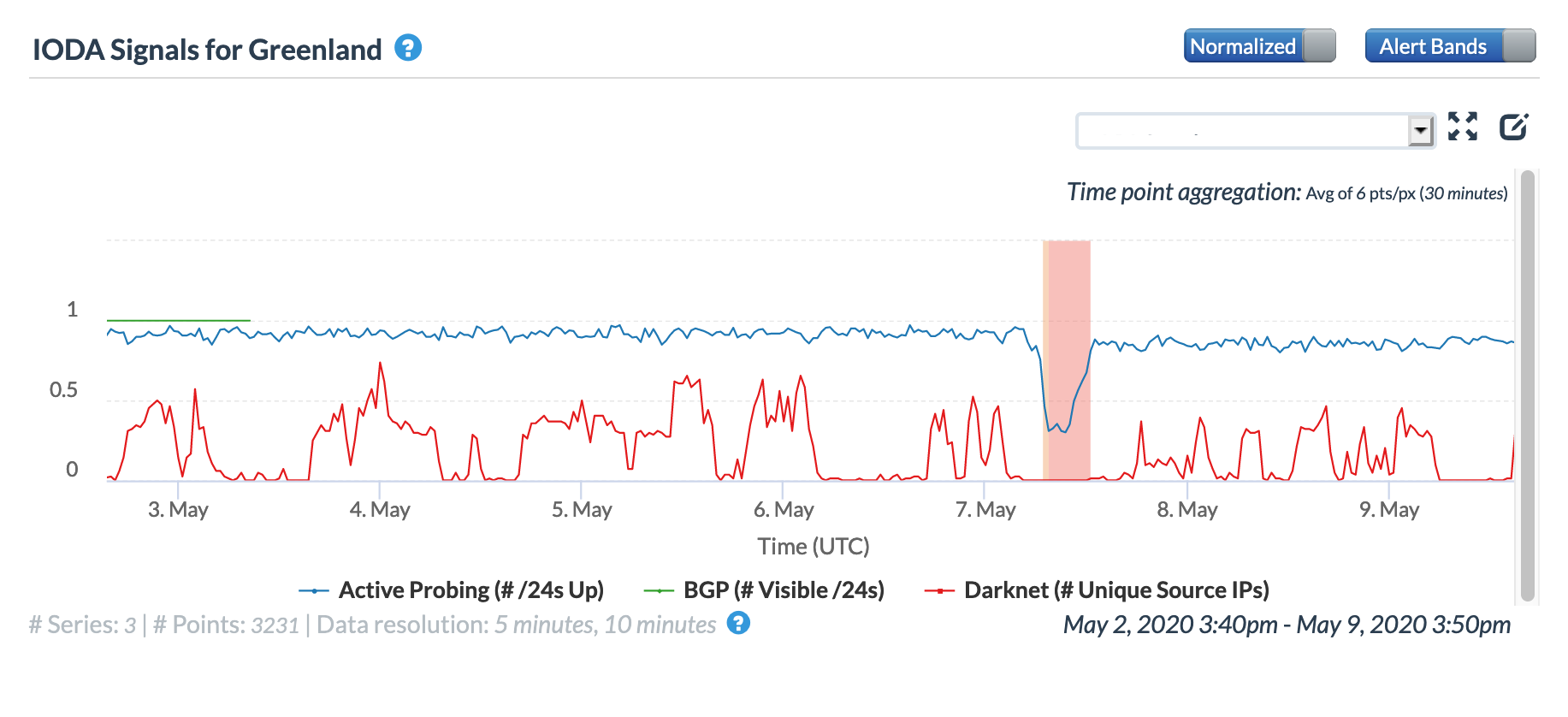

According a May 7 post to its Facebook page, Greenland network provider TELE-POST suffered an unspecified network issue that disrupted Internet connectivity for DSL users.

Visible in the graphs below, it appears that the disruption began around 06:30 GMT, and lasted for just over six hours. However, after the issue was addressed and connectivity restored, TELE-POST customers continued to have issues with Wi-Fi connectivity, leading to a series of additional Facebook posts (1, 2, 3) that provided situational updates and guidance on resetting modems.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Greenland, May 7

CAIDA IODA graph for Greenland, May 7

CAIDA IODA graph for AS8818 (TELE-POST / Tele Greenland), May 7

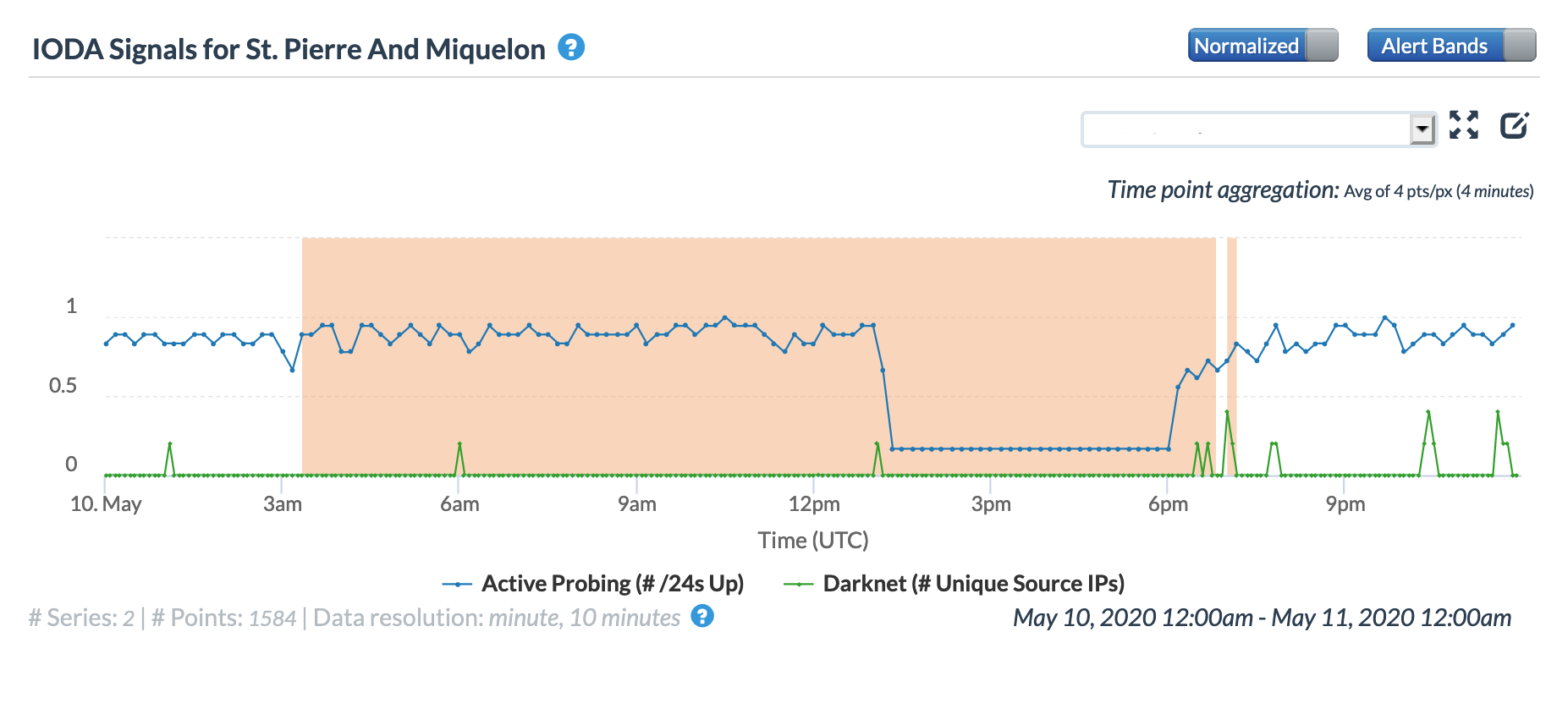

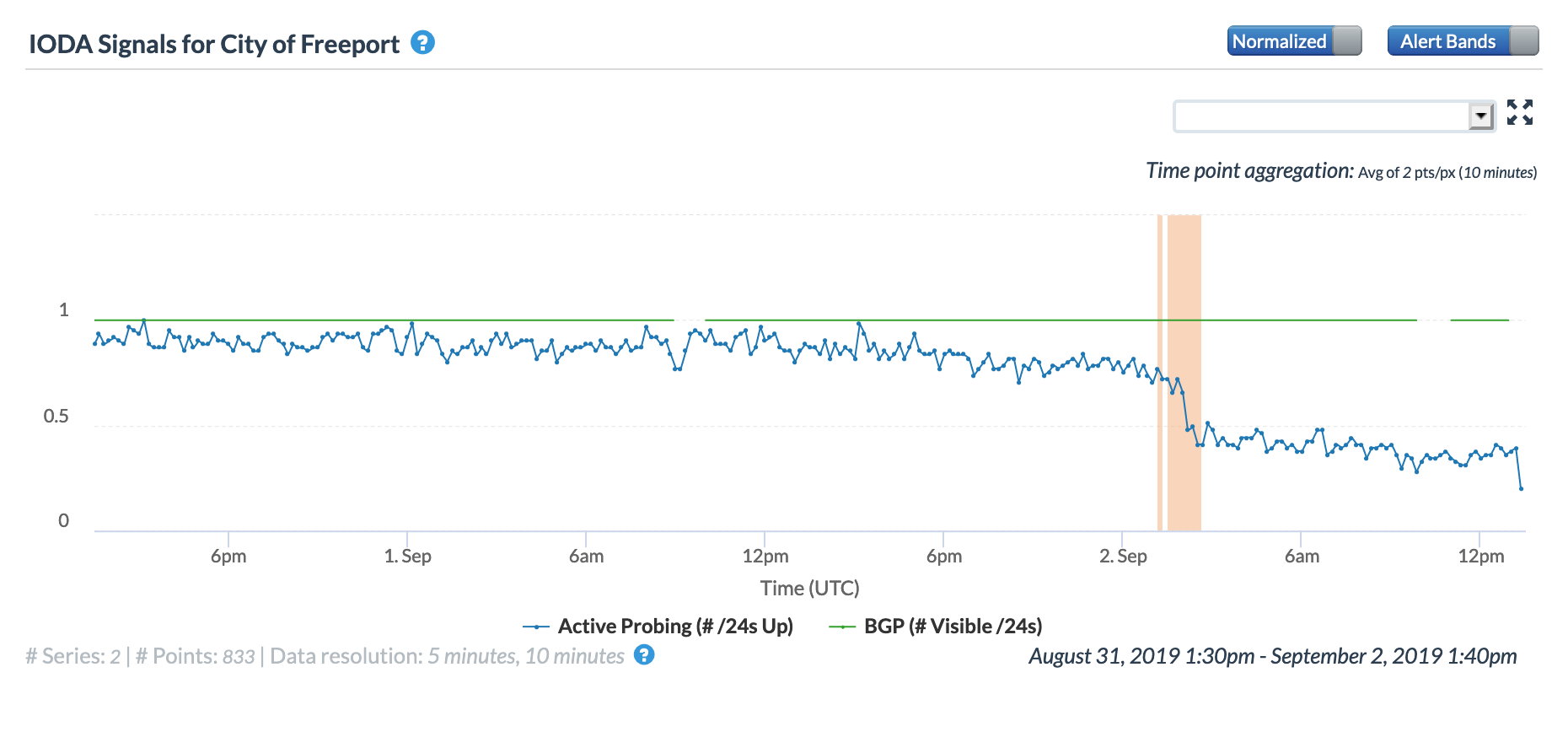

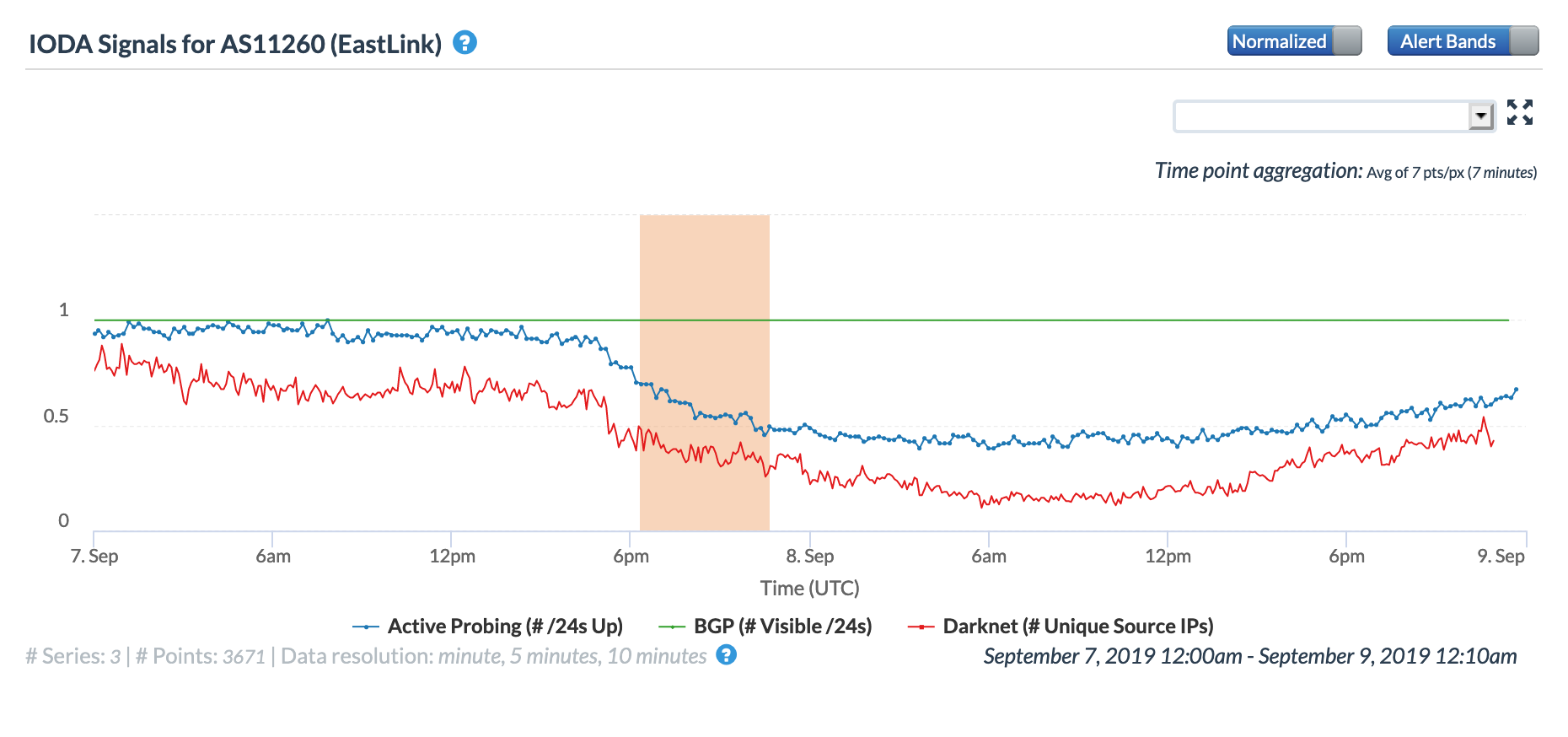

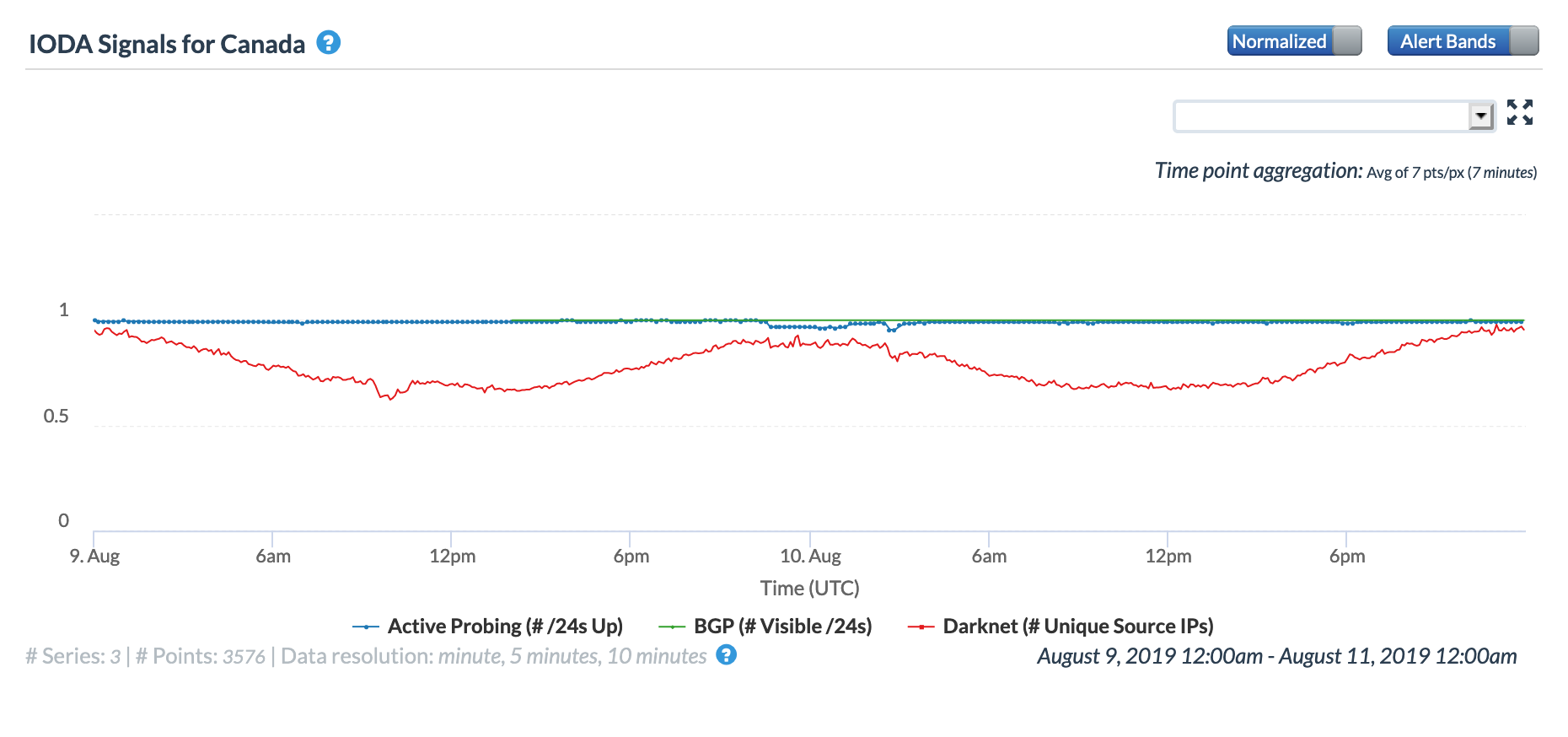

The French territory of St. Pierre and Miquelon, located south of the Canadian island of Newfoundland, experienced a multi-hour Internet disruption on May 10. The graphs below show that the disruption began around 13:00 GMT, with connectivity restored about five hours later. Both the Oracle and CAIDA graphs show a significant decline in the active probing metrics, and the Oracle graph shows a similar decline in the BGP metric.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for St. Pierre and Miquelon, May 10

CAIDA IODA graph for St. Pierre and Miquelon, May 10

We're aware that customers in Harbour Breton and parts of Burin Peninsula are currently experiencing an interruption in service. We're investigating the cause and working to restore service as quickly as possible. We appreciate your patience and will update later this afternoon.

— Eastlink Support (@EastlinkSupport) May 10, 2020

The Tweet shown above from the support account of Canadian Internet provider Eastlink notes that the network was experiencing a service interruption. This interruption is evident in the Oracle graph below for AS11260 (Eastlink), and also in the graph below for AS3695 (SPM Telecom), which uses Eastlink as its primary upstream provider.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS11260 (Eastlink), May 10

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS3695 (SPM Telecom), May 10

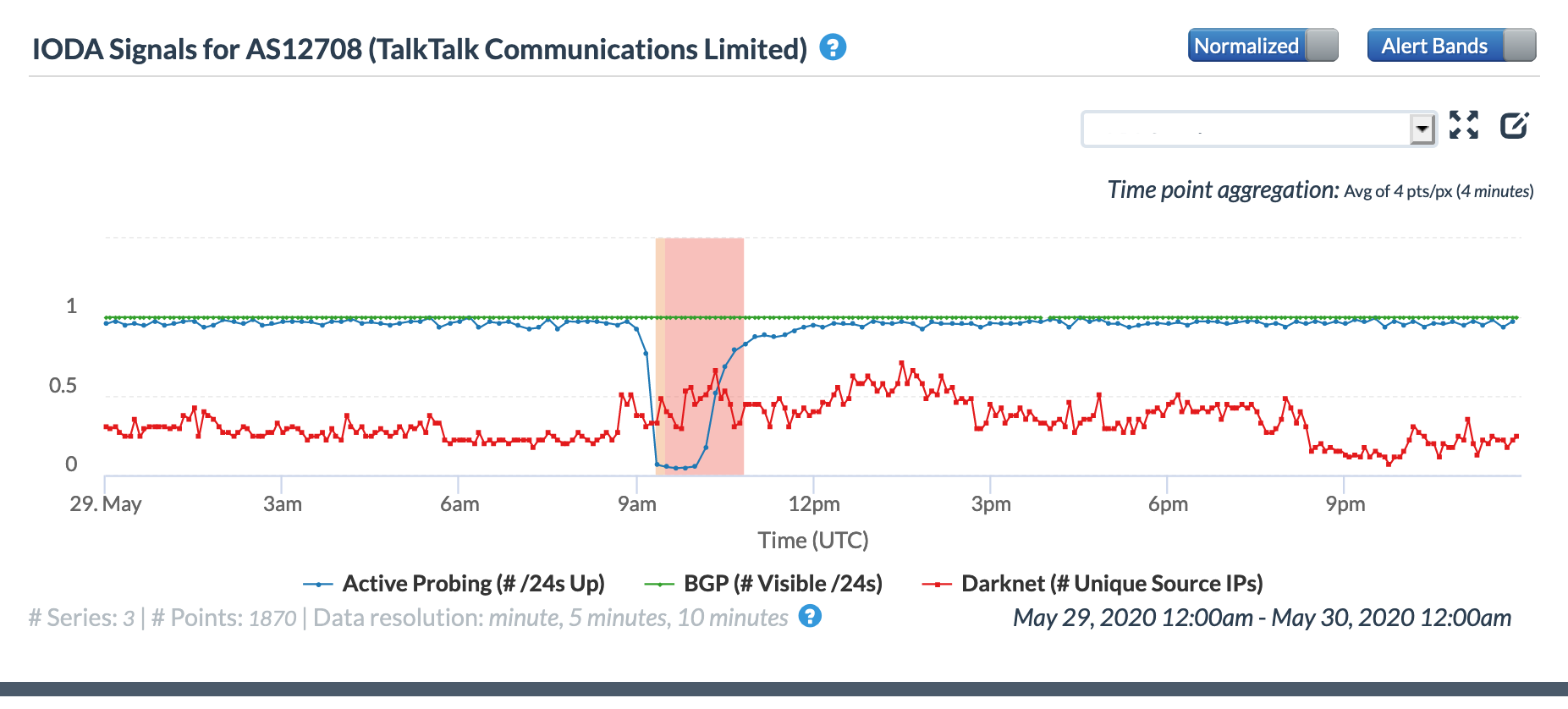

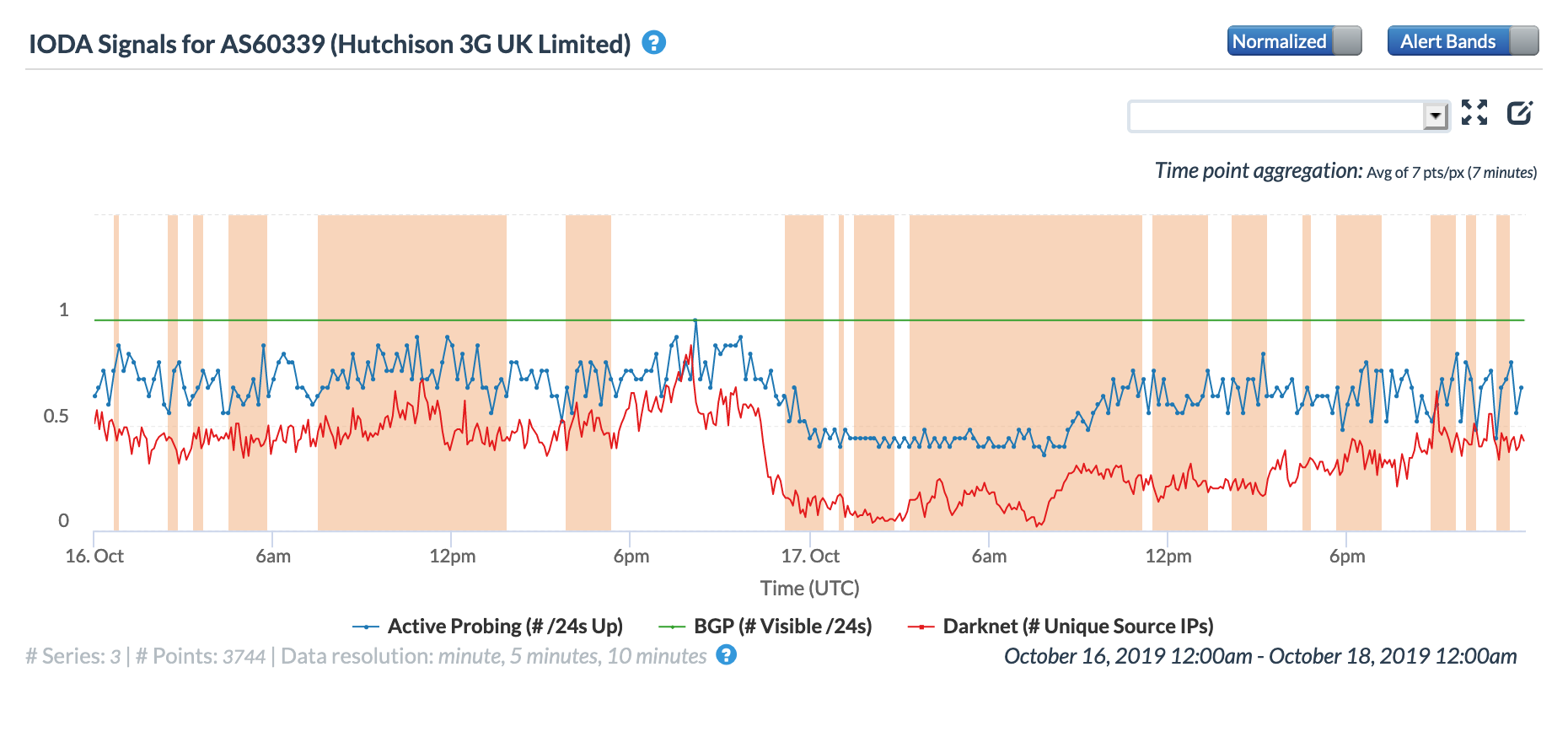

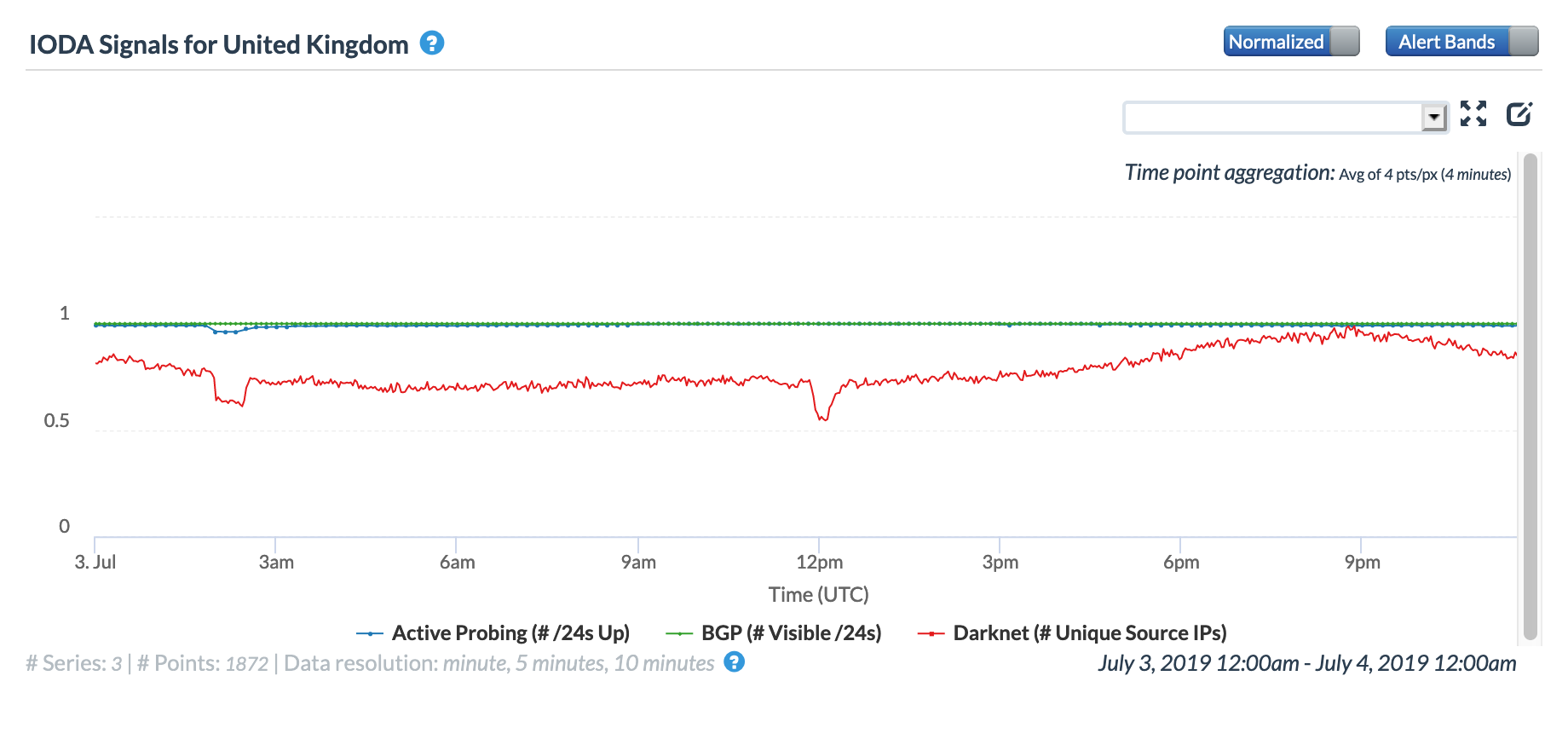

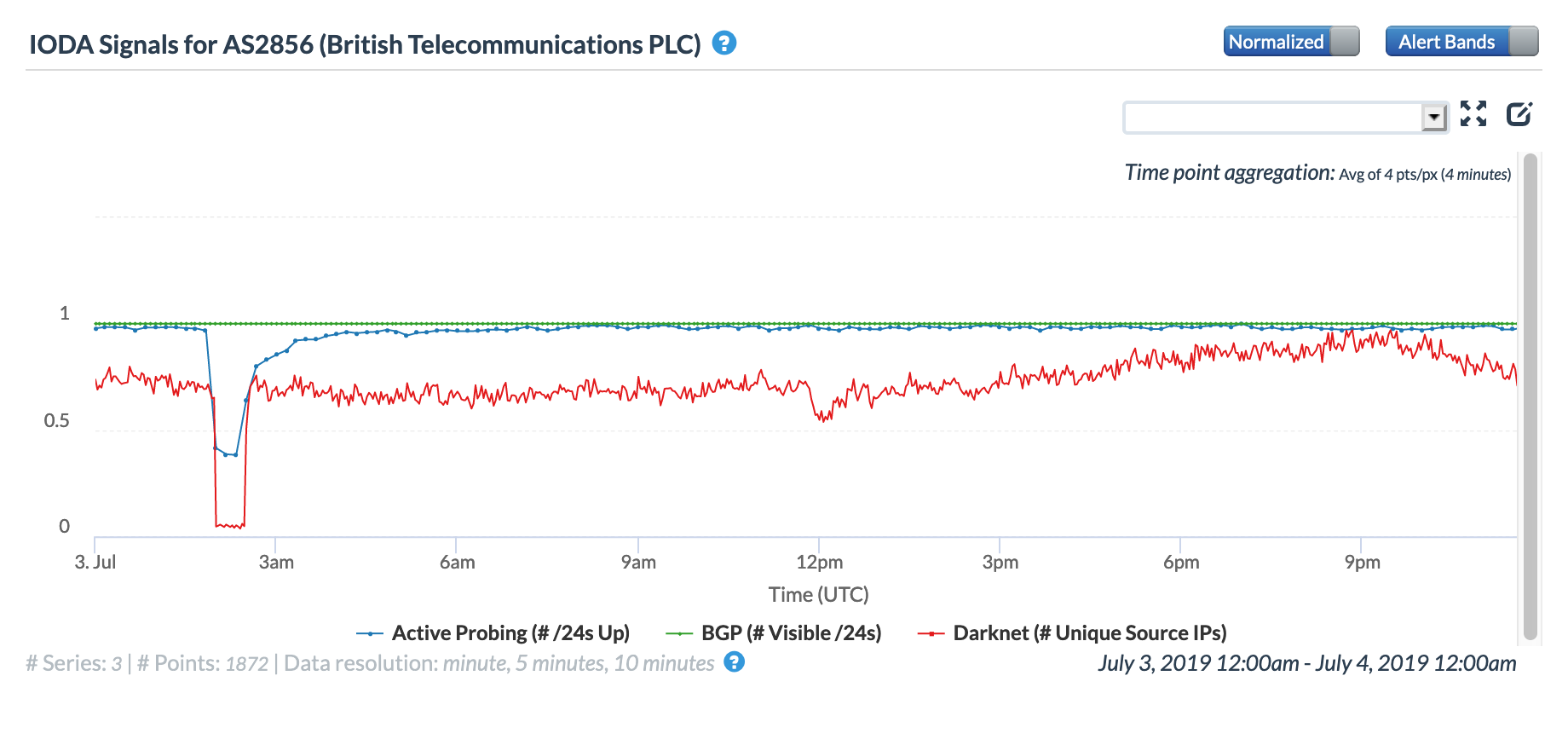

Thousands of TalkTalk users in the United Kingdom experienced an Internet disruption for a couple of hours during the morning of May 29. While the disruption was covered in articles published on the Web sites of the Independent and the Daily Mail, neither included any information on the root cause of the issue. TalkTalk acknowledged the problem in Tweeted replies to customer complaints, but did not provide any information on what caused the disruption.

The graphs below show that the disruption began approximately 09:00 GMT and lasted for approximately 90 minutes, which is consistent with the timeline in the published reports. The active probing metric in the CAIDA graphs shows an obvious decline, while the Darknet metric remained largely unaffected, as did the BGP metric.

CAIDA IODA graph for AS13285 (TalkTalk), May 29

CAIDA IODA graph for AS12708 (TalkTalk), May 29

Fing Internet Alerts outage graph for TalkTalk, May 29

Conclusion

Over the last several month, COVID-19 lockdowns and social distancing have driven nearly everyone onto the Internet for school, work, shopping, and entertainment. Given this increased reliance on the Internet for everyday life, it is imperative that network providers do a better job of communicating about Internet shutdowns, outages, and other disruptions that impact their networks. Ideally, this communication would be proactive and public, posted on status pages/sites (and archived for future reference), as well as to associated Twitter accounts and Facebook pages. (And by acknowledging issues in a timely fashion, and communicating about them openly, providers can control the narrative around such events, preventing rumors from spreading, and even potentially buying themselves a little customer goodwill.)

At the very least, providers need to respond in a timely fashion to inquiries about Internet disruptions observed on their networks made via social media and/or e-mail. In this day and age, given the importance of Internet connectivity, ignoring these inquiries is simply unacceptable.

]]>While this blog has never claimed to be exhaustive in its coverage of Internet disruptions, it has endeavored to catalog the various causes of those disruptions, and most months see quite a few documented causes. Interestingly, March only saw documented disruptions due to power outages and cable/fiber issues, with a couple of additional due to possible network issues. (There were, of course, a number of other observed disruptions, but root causes were unable to be identified or confirmed through research or social media outreach.)

Power Outages

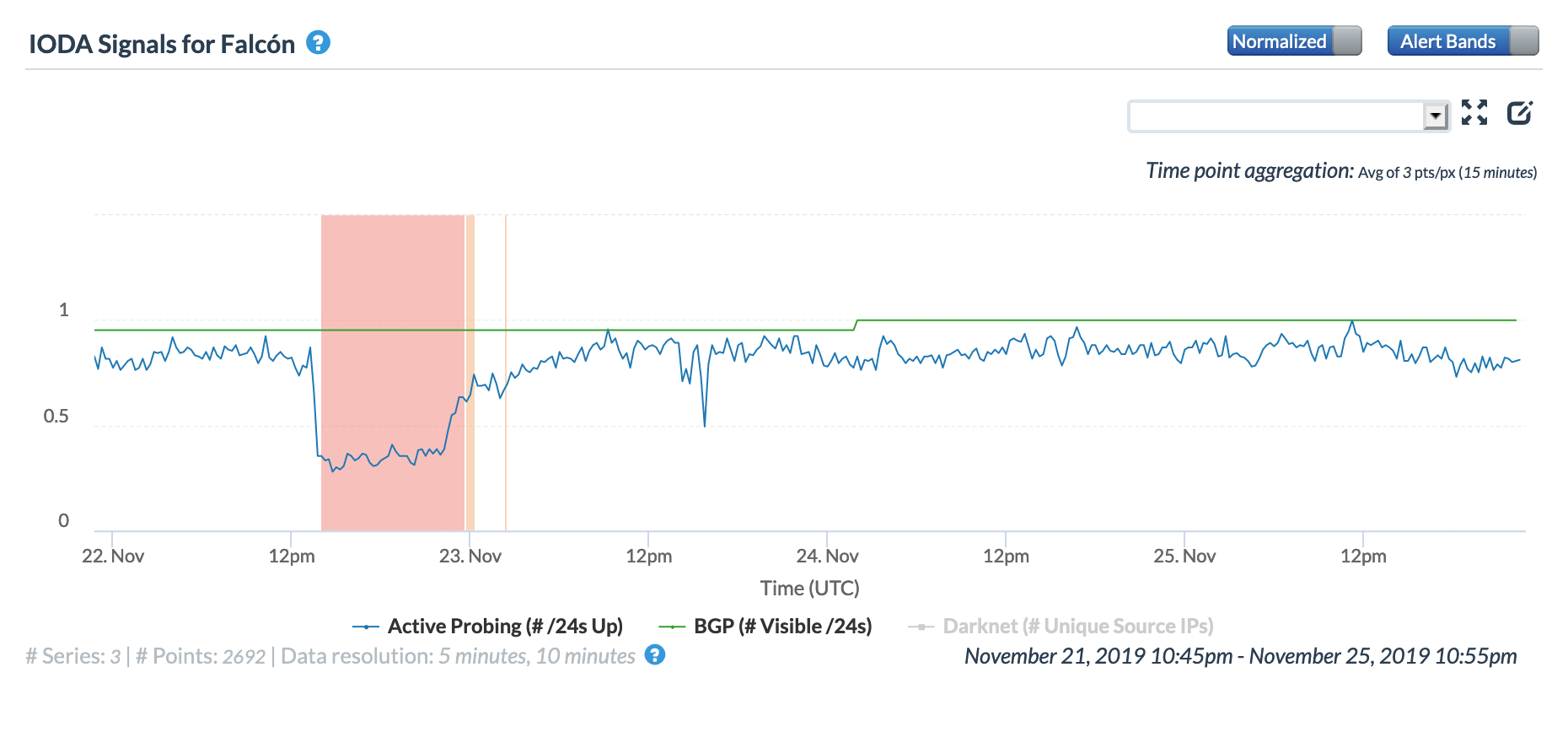

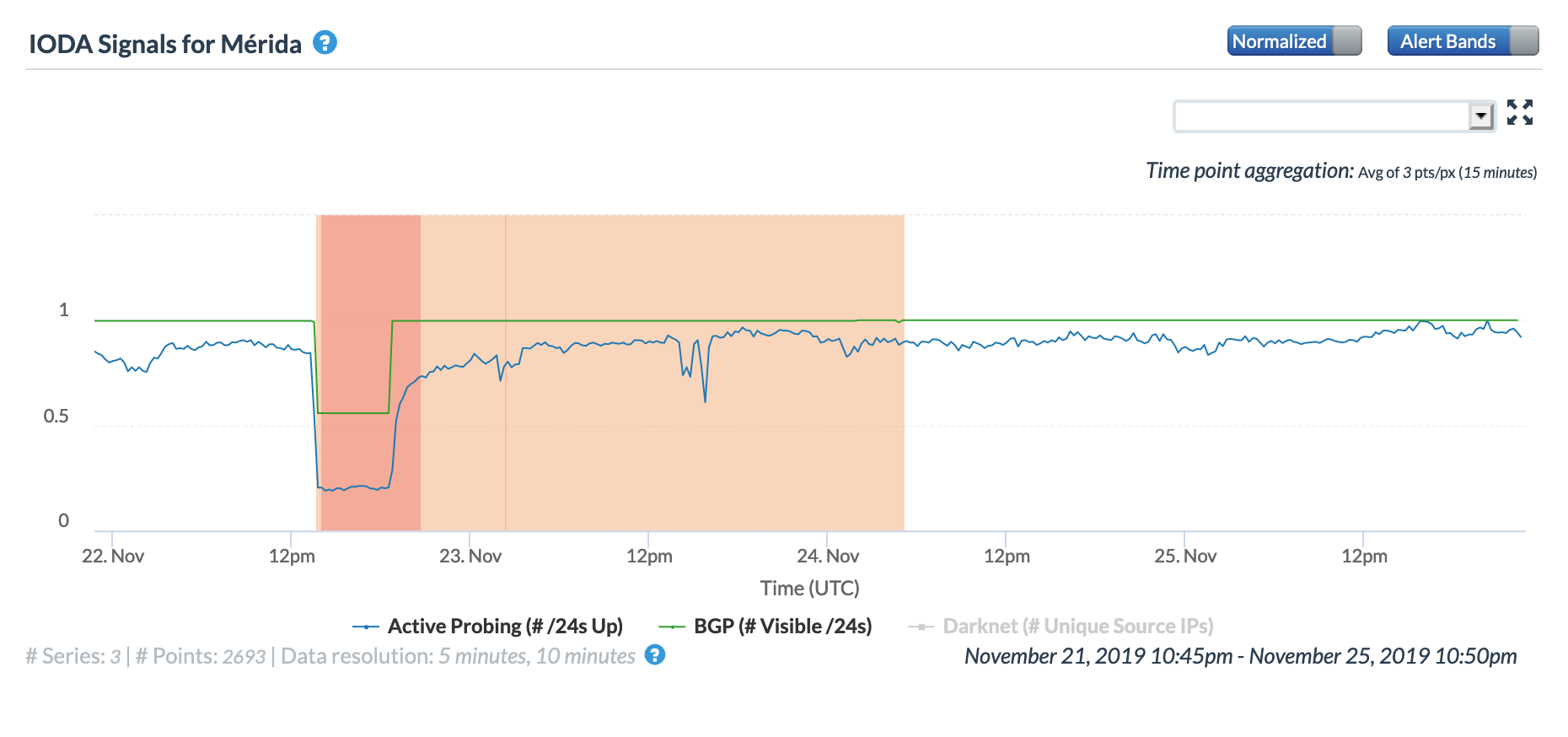

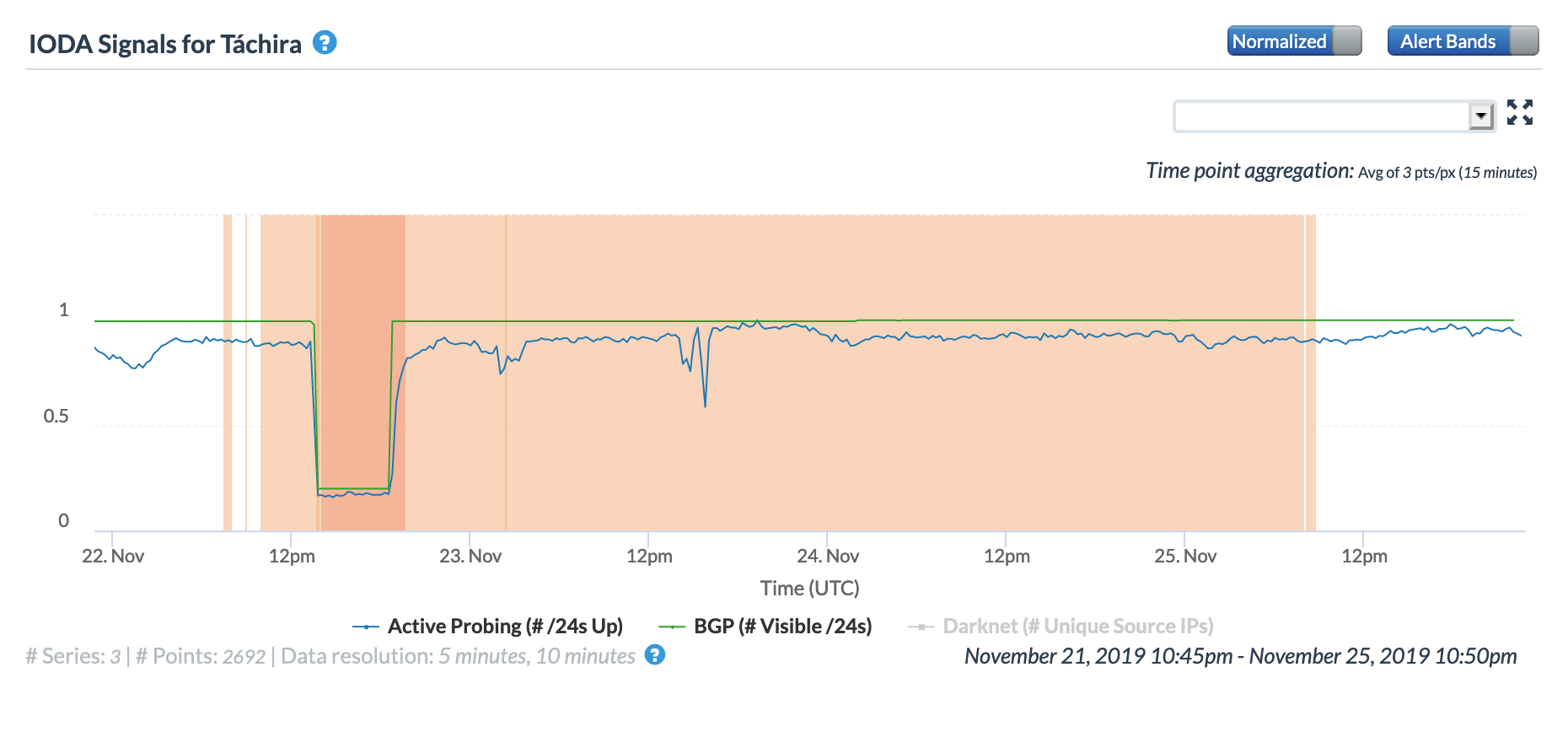

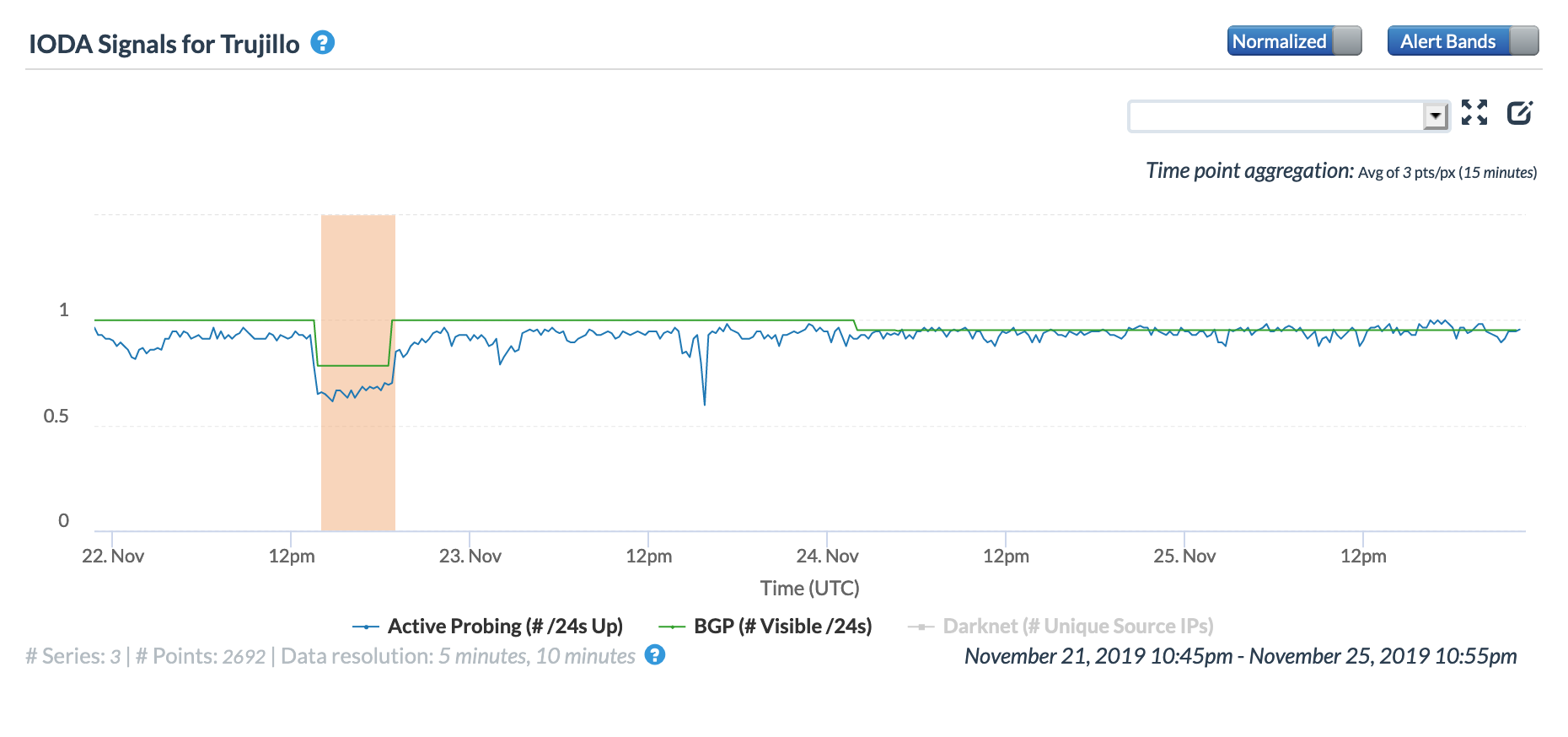

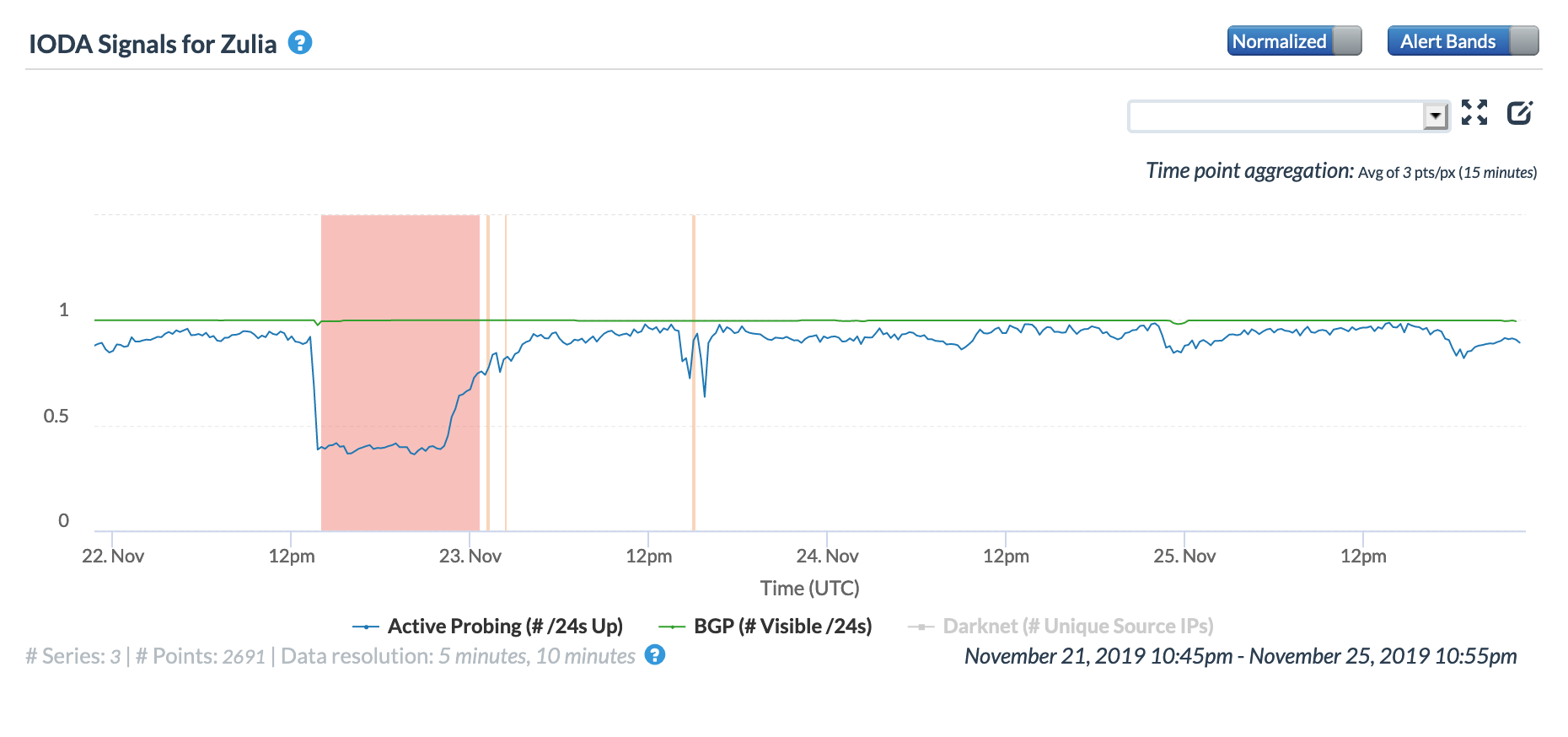

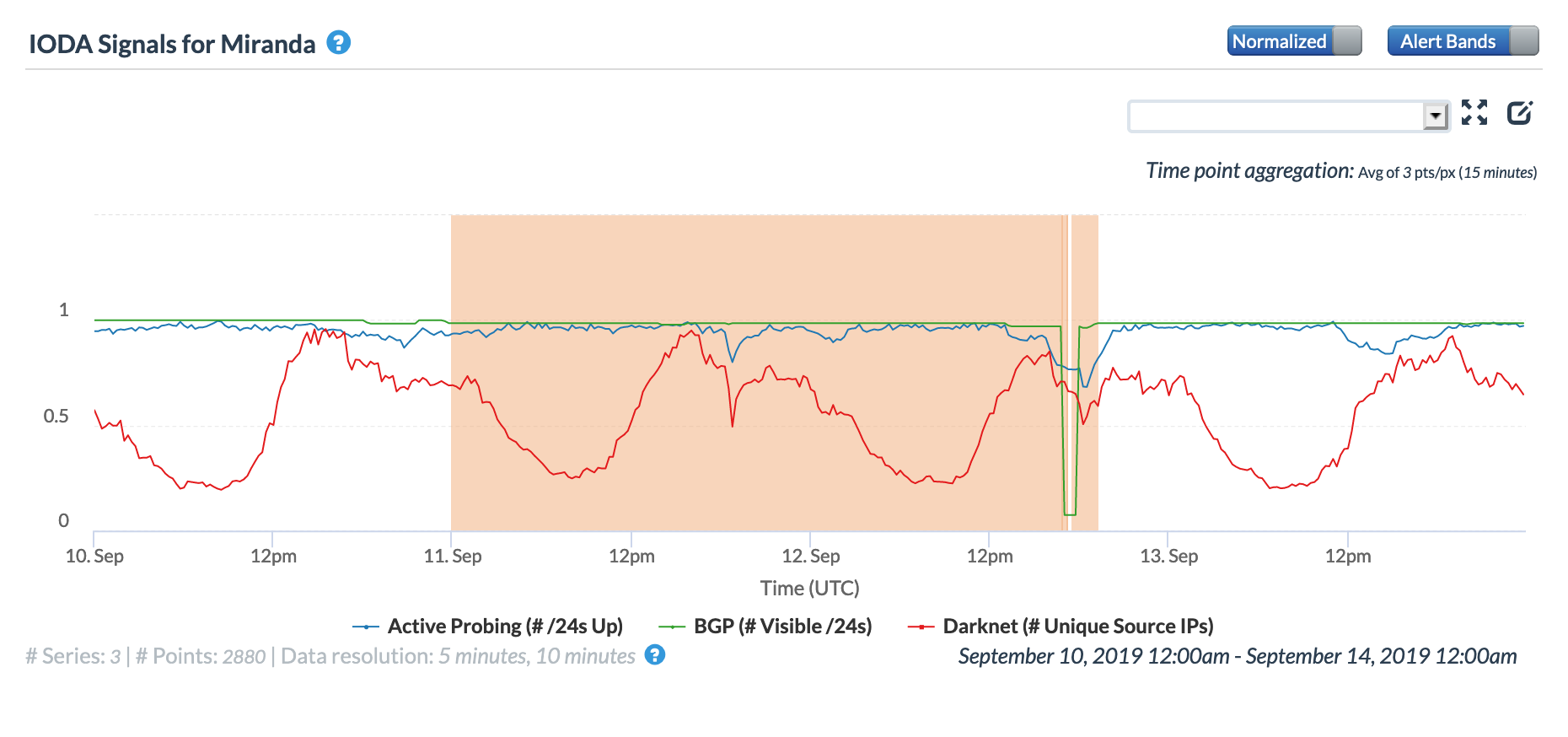

Unfortunately, the instability of Venezuela’s electrical power infrastructure has been the cause of Internet disruptions within the country multiple times in the past. During March, NetBlocks Tweeted about seven distinct Internet disruptions due to power failure in Venezuela – these occurred on March 1st, 3rd, 5th, 8th, 12th, 20th, and 26th. The four graphs below illustrate CAIDA IODA Active Probing results across 15 Venezuelan states across the month (one graph per week). For the disruptions visible on the dates highlighted by Netblocks, Táchira was one of the states with the most significant impact, as was Merida. It is interesting to note that similar Internet disruptions are also visible on March 7th, 9th, 13th, and 28th, although it is not clear whether these were also due to power outages in the affected states – Táchira appears to be impacted by these as well.

CAIDA IODA multi-state graph for Venezuela, March 1-7

CAIDA IODA multi-state graph for Venezuela, March 8-14

CAIDA IODA multi-state graph for Venezuela, March 15-21

CAIDA IODA multi-state graph for Venezuela, March 22-28

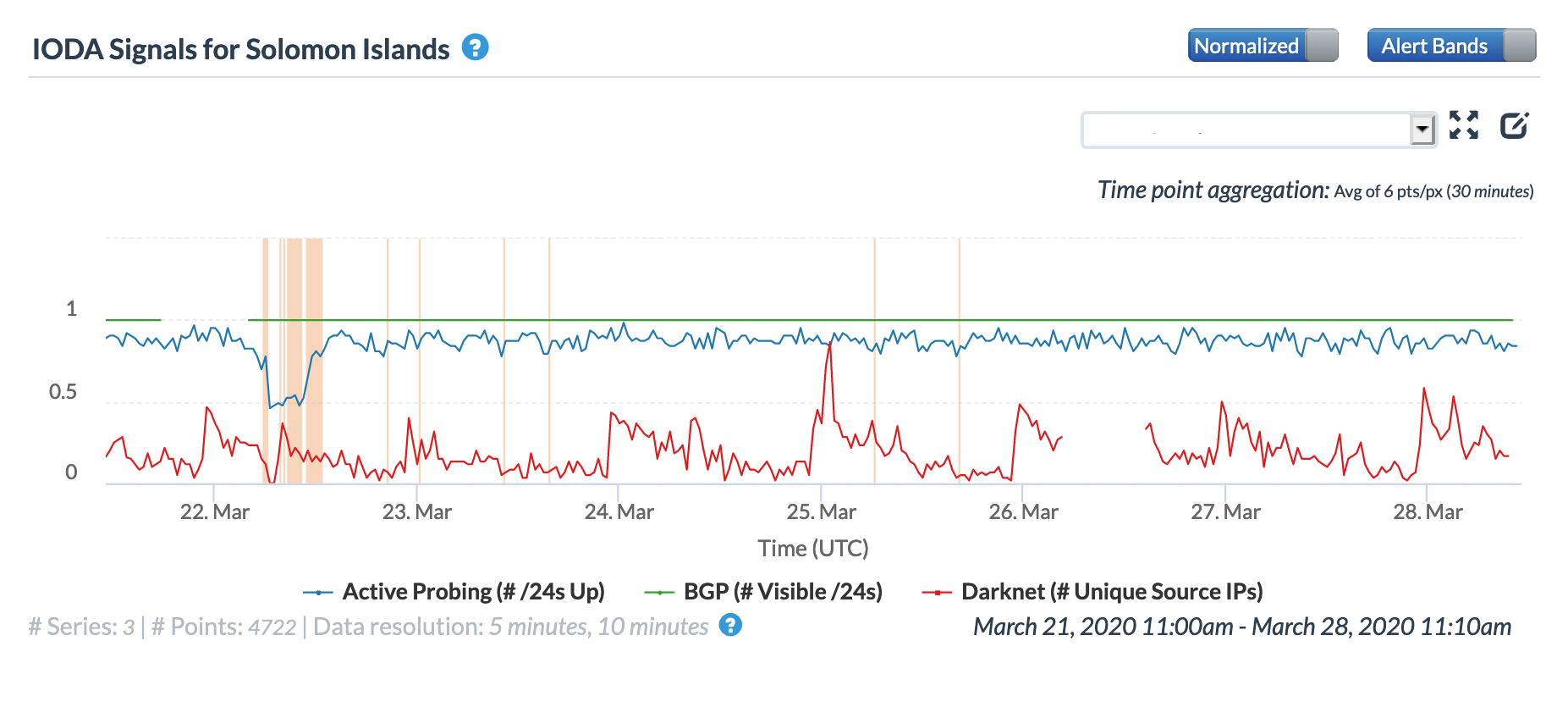

On March 22, a power outage also disrupted Internet connectivity on the Solomon Islands. Our Telekom (Solomon Telekom Company Limited), a local telecommunications service provider, posted on its Facebook page that its main exchange had experienced an outage due to a power failure. This outage is clearly visible in both the country- and network-level graphs below, starting around 0620 GMT, and ending around 1400 GMT.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Solomon Islands, March 22

CAIDA IODA graph for Solomon Islands, March 22

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS45891 (Solomon Telekom), March 22

CAIDA IODA graph for AS45891 (Solomon Telekom), March 22

Cable/Fiber Issues

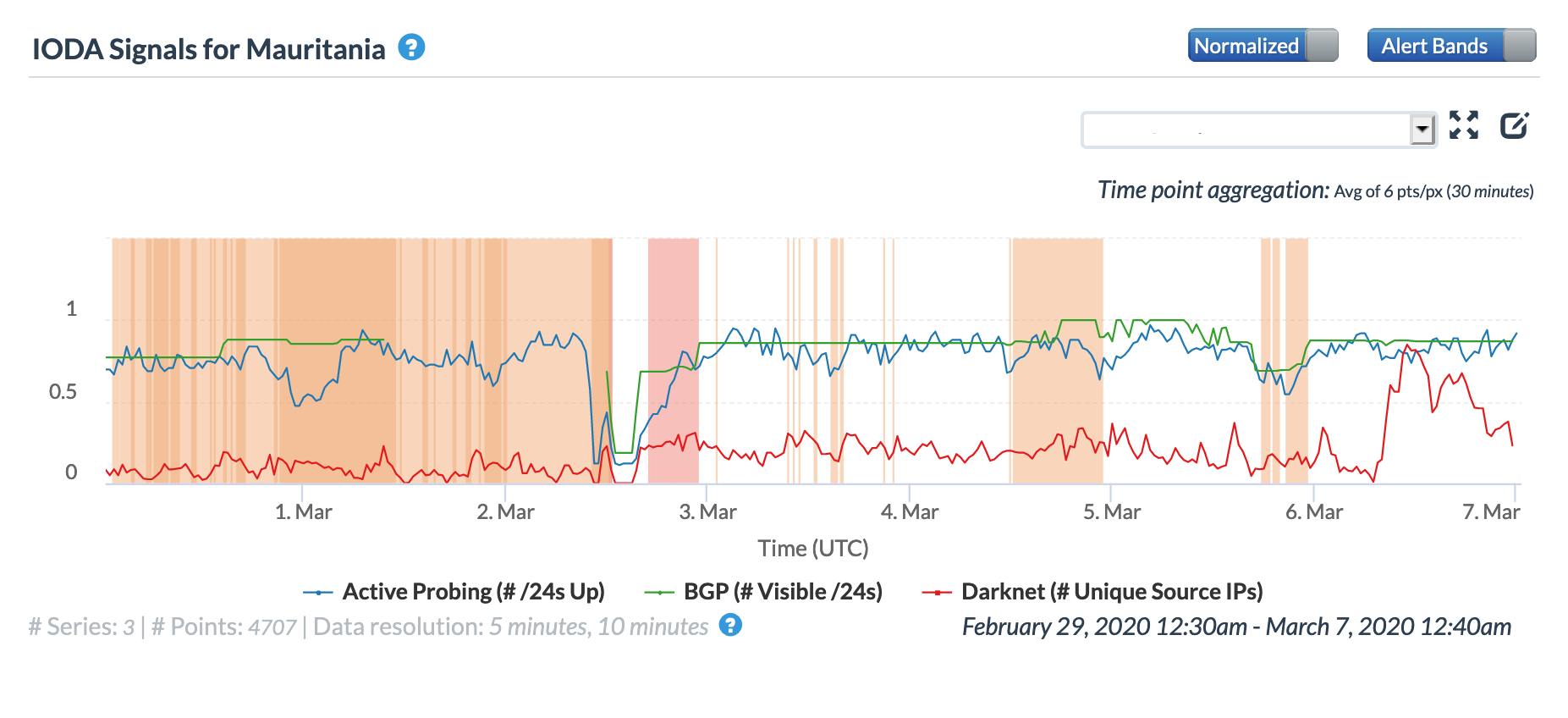

On March 6, Oracle Internet Intelligence Tweeted that a new fault in a segment of the ACE submarine cable was impacting connectivity in Mauritania. The disruption is clearly visible in both the Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA graphs below, starting mid-afternoon GMT, with partial recovery early the following day.

Although unconfirmed, the disruption visible in both graphs several days prior may also be related to problems with the ACE cable. On March 2, the CAIDA graph shows that all three measured metrics dropped shortly before noon GMT, with a gradual recovery taking place through the rest of the day, presumably as traffic shifted to alternate paths. In the Oracle graph, the active probing and BGP graphs showed concurrent drops as expected, but the DNS Query Rate graph spiked, indicating that whatever outbound traffic that actually made it out of Mauritania likely included requests by recursive resolvers driven by constant retries (due to lack of response) from DNS clients.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Mauritania, March 2

CAIDA IODA graph for Mauritania, March 2

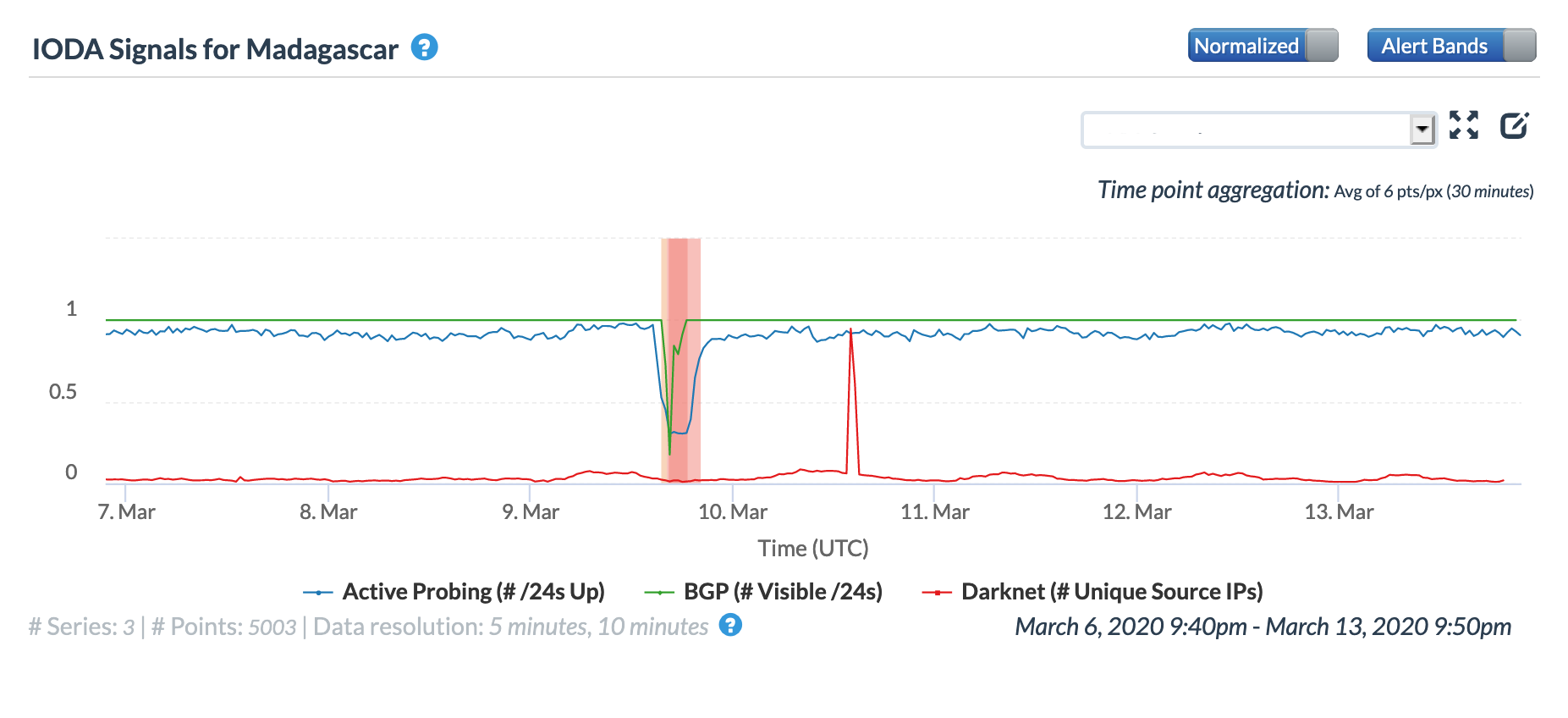

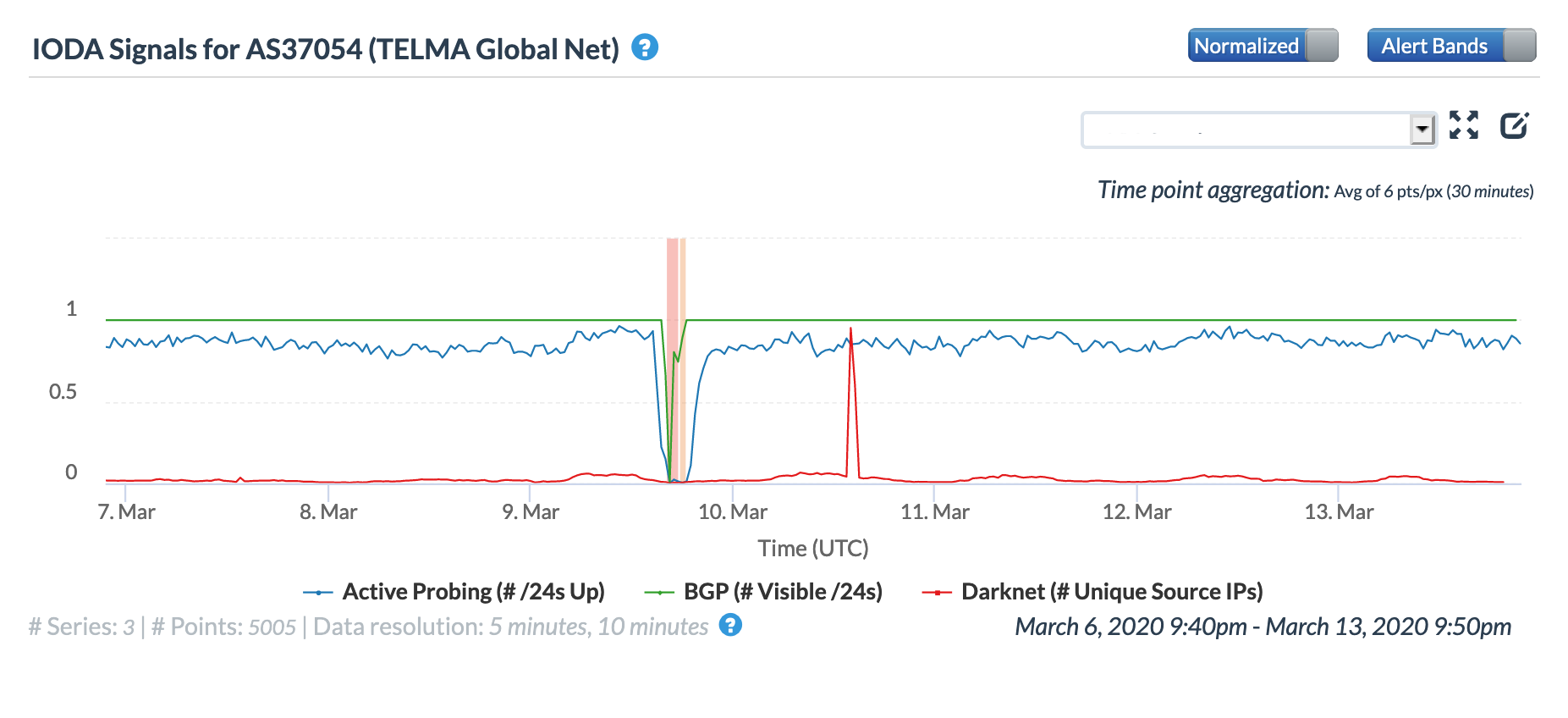

On March 9, Madagascar suffered an Internet disruption reportedly caused by roadwork severing a fiber optic cable. According to a published report (via Google Translate),

“At the end of yesterday afternoon, Internet users had the unpleasant surprise of not being able to access the Internet. It is a total cut causing discomfort to users, especially those who work on the Internet and use the Telma network. It was only in the early evening that everything returned to normal, much to everyone’s relief. According to a source with Telma, the cut comes from road works carried out in the southern part of the country and having affected the optical fiber. It was thus necessary to carry out a back up, either a reconnection or failover, on Lion cable to satisfy the users. It is a common practice between operators in case one of the companies is in a delicate situation as was Telma yesterday. Contrary to the claims of some science fiction enthusiasts, it is indeed a technical failure and not another reason.”

The mid-afternoon disruption is visible at a country level in the figures below, impacting both the active probing and BGP metrics. As the quote above notes, TELMA (Telecom Malagasy) was also impacted – the graphs below illustrate that the active probing metrics declined in both Oracle’s and CAIDA’s measurements, while Oracle’s measurements also show a sharp increase in latency during the period of disruption.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Madagascar, March 9

CAIDA IODA graph for Madagascar, March 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS37054 (TELMA Global Net), March 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS37054 (TELMA Global Net), March 9

On March 10, Gabon Telecom alerted its users via Twitter (see below) and Facebook that a cut to the SAT-3 submarine cable disrupted Internet traffic to its fixed network the day before. The post also references the ACE submarine cable cut in Mauritania discussed above, and appears to claim that the repairs to the ACE cable, which also connects to Gabon, will help [restore] Gabon Telecom’s traffic.

COMMUNIQUÉ pic.twitter.com/XAleUwmGfK

— Gabon Telecom (@gt_officiel) March 10, 2020

After posting a status update on March 11, Gabon Telecom confirmed the restoration of service on March 12. The figures below show that the associated Internet disruption lasted from March 9 -12 at both a country and network level. At a country level, the impact of the cable problems appears to be more severe in the CAIDA measurements than in Oracle’s, likely owing to the difference in the respective measurement vantage points. At a network level, the initial disruption is visible as a brief outage in the Oracle Internet Intelligence graph, although traffic from Gabon Telecom quickly began transiting a new upstream provider, but with increased latency. The graph shows that the latency returned to normal after the cable was repaired, although the upstream provider remained the same. On March 12, Gabon Telecom also notified customers that it would be granting up to 5 GB of additional mobile data to those impacted.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Gabon, March 9-12

CAIDA IODA graph for Gabon, March 9-12

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS16058 (Gabon Telecom), March 9-12

CAIDA IODA graph for AS16058 (Gabon Telecom), March 9-12

On March 12, Oracle Internet Intelligence Tweeted that a historic “dragon storm” was impacting Internet connectivity in Egypt. The graphs below show nominal disruptions to the active probing metrics, becoming most evident around mid-day GMT. Interestingly, the traffic-related metrics in both graphs also saw significant declines, with the diurnal patterns effectively flattening out. Telecom Egypt explained in a LinkedIn post on March 18 that “The service was interrupted in few segments located in Egypt as a result of terrestrial cable cuts resulting from the unusually powerful storm, recognized as the fiercest to hit the country in over 25 years, and accompanied by heavy rainfall, destructive winds, and dust storms, causing large-scale power disruptions in multiple areas in Egypt.”

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Egypt, March 12

CAIDA IODA graph for Egypt, March 12

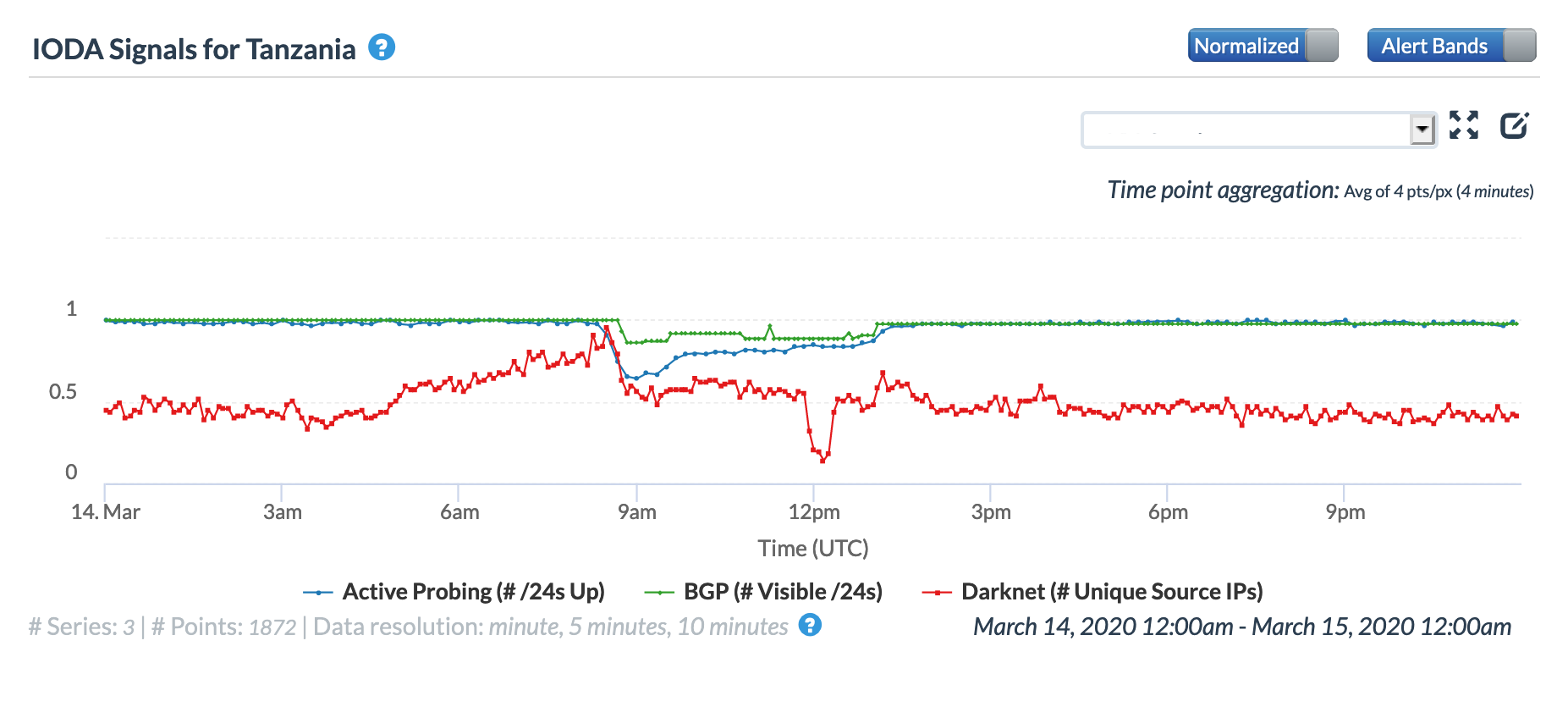

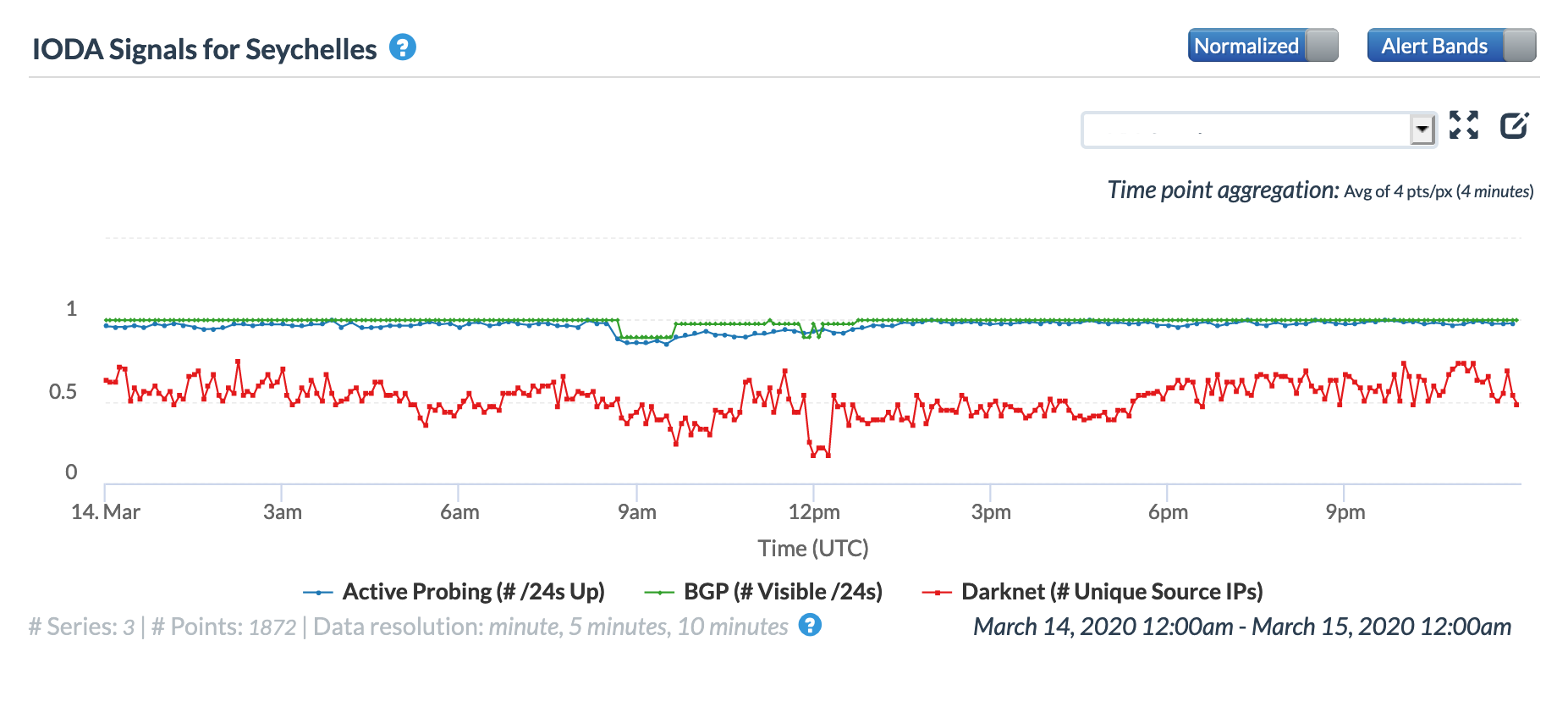

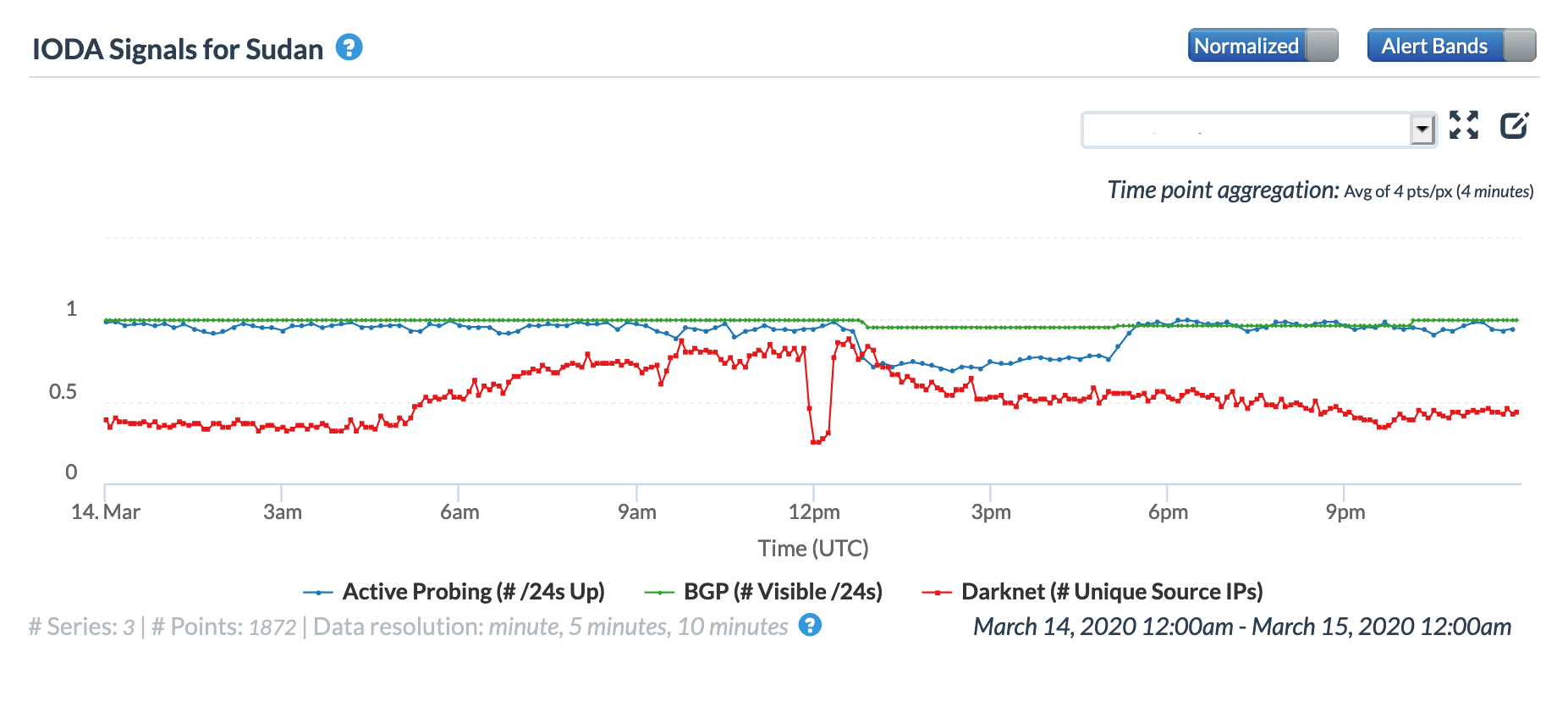

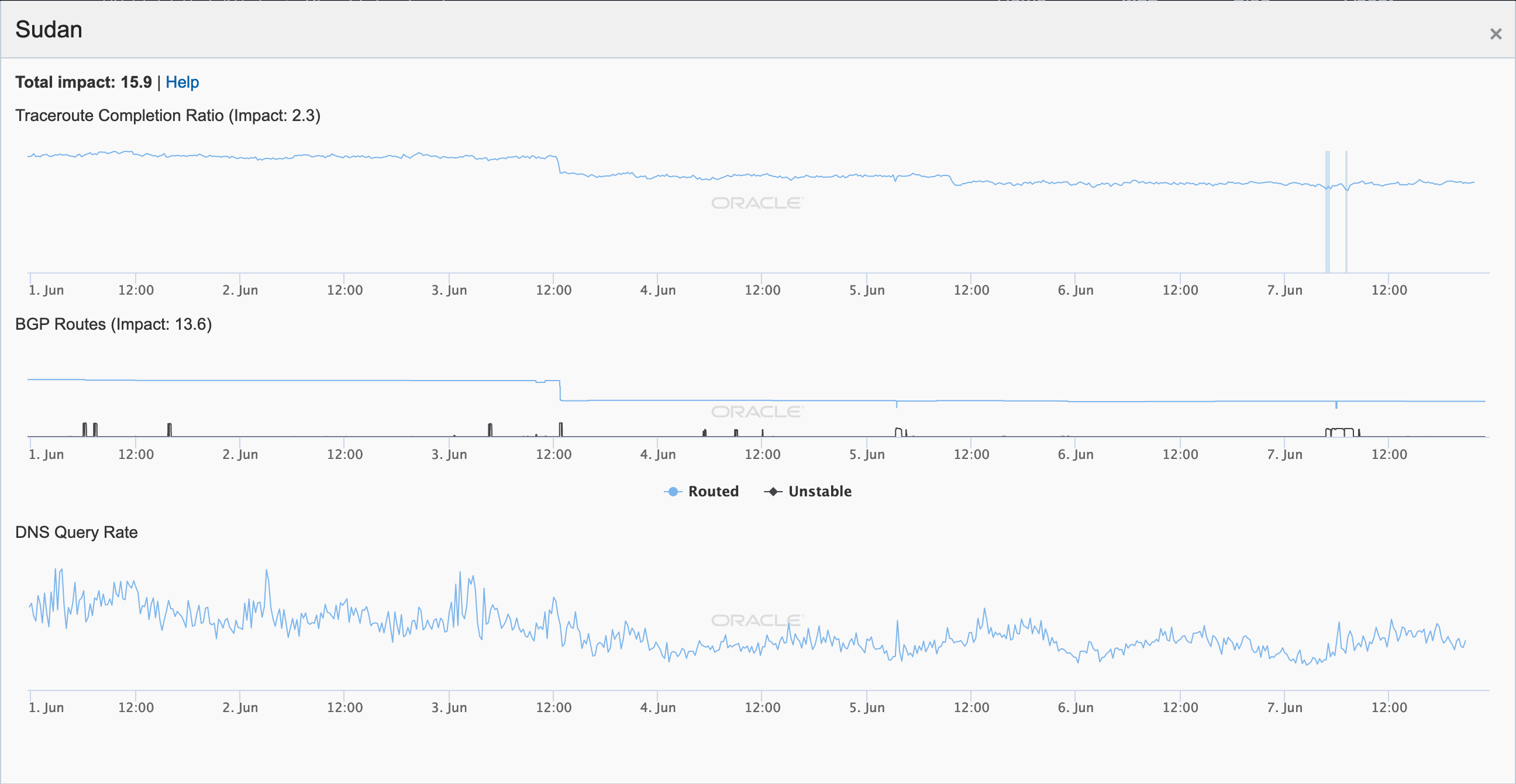

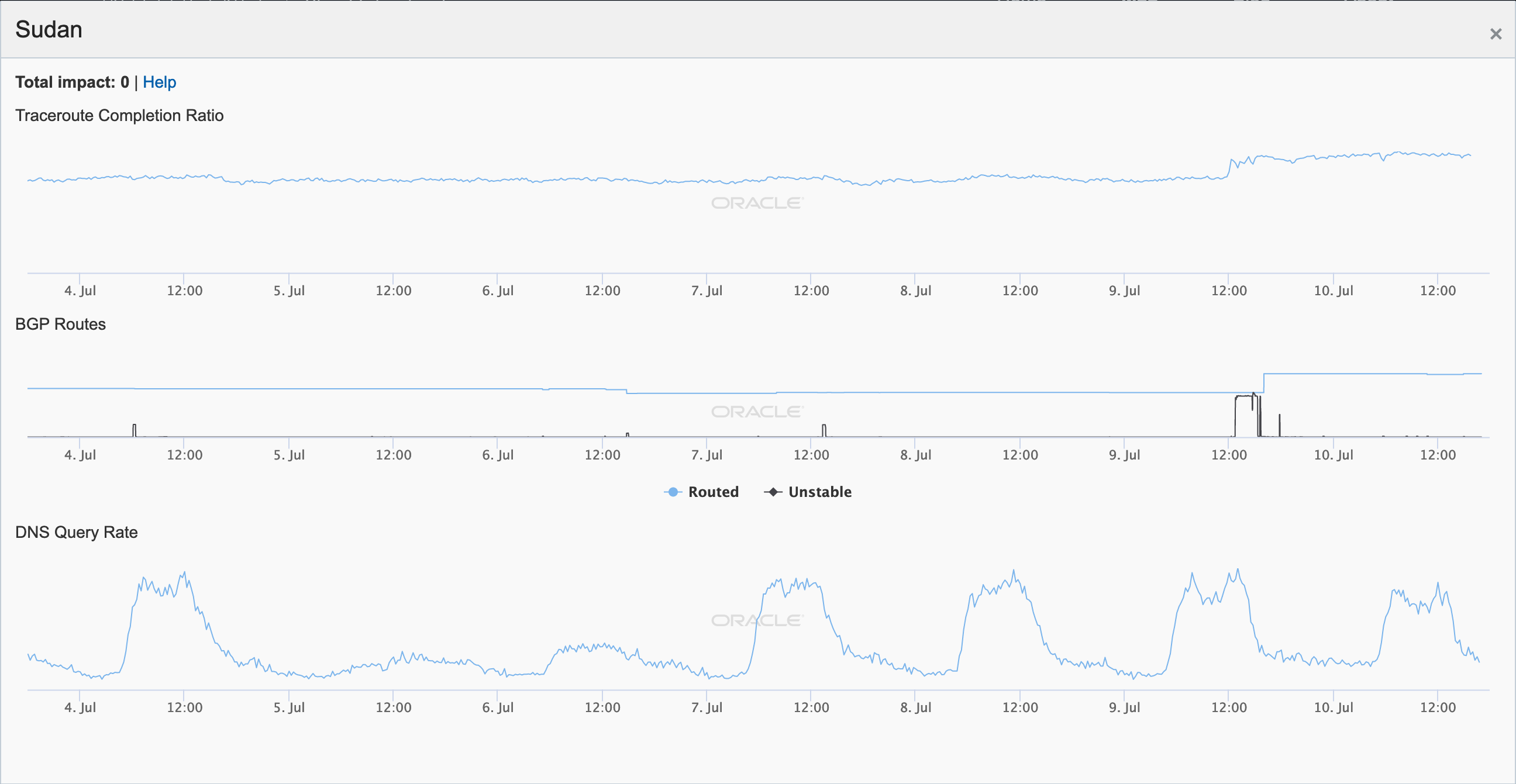

A cable issue on March 14 impacted Internet connectivity across more than a dozen countries. Initially reported by Oracle Internet Intelligence as a submarine cable cut, a subsequent Tweet clarified that the subsea cable outage was caused by a cut in terrestrial fiber optic in Egypt. According to the Tweet below, the problem was with the EASSy cable system. (A submarine cable industry observer explains that Egypt is a critical transit cross road for international East-West cables, as well as terrestrial and submarine diversified backhaul links beween Suez Canal North (Alexandria / Port Saïd) and South (Suez) landing stations.)

EASSy cable system is down due to a terrestrial fault in Egypt between Abu Talat and Zaafarana on the Djibouti to Marseilles segment. We are waiting for confirmation as to where the SEACOM break occurred and whether this is in the same location.

— SA NREN Operational Updates & Alerts (@RENAlerts) March 14, 2020

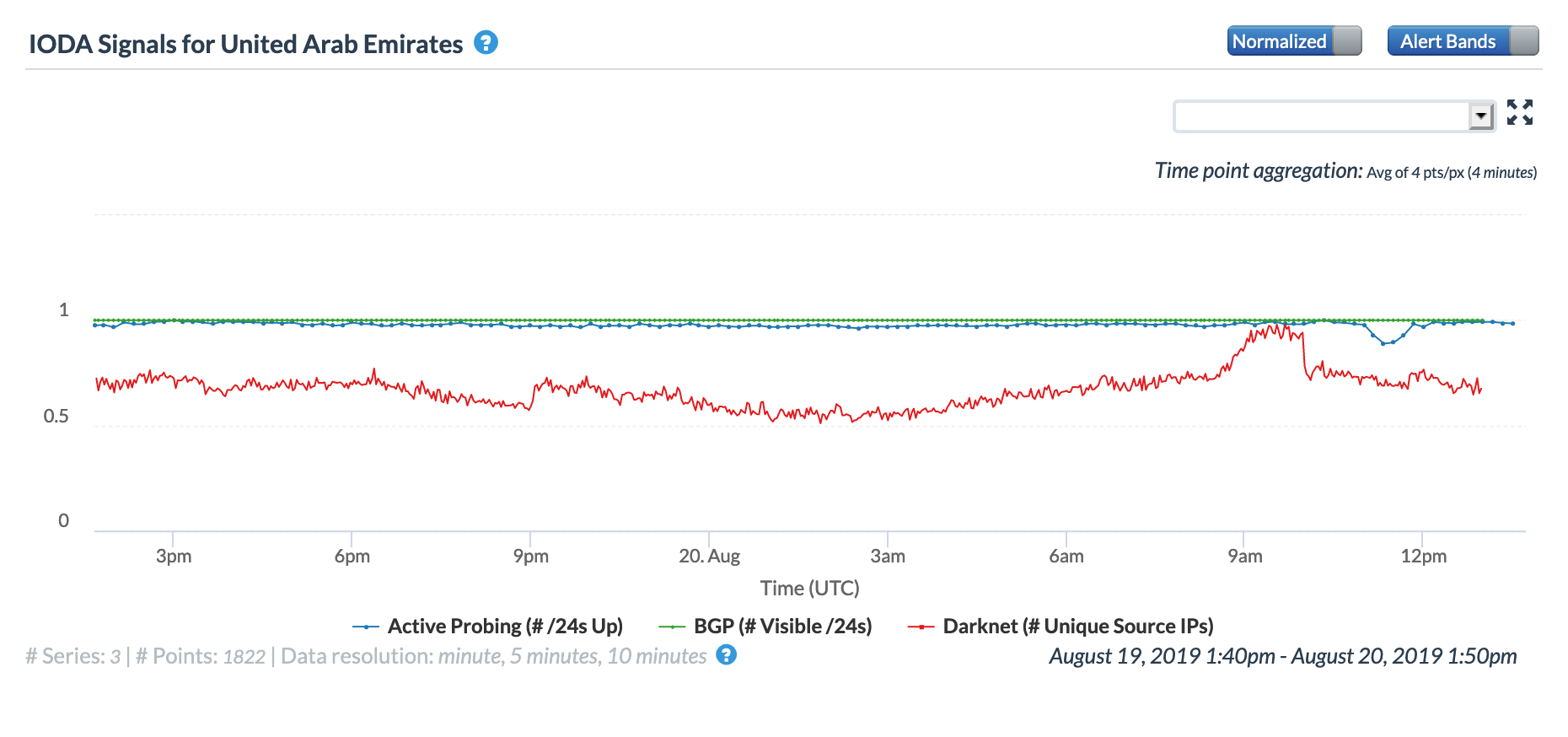

The graphs below show the impact of the issue at a country level in Burundi, Djibouti, Tanzania, Seychelles, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates. In the United Arab Emirates, the disruption is barely evident in the active probing and BGP metrics, but it is significantly more visible across the other countries.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Burundi, March 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Burundi, March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Djibouti, March 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Djibouti, March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Tanzania, March 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Tanzania, March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Seychelles, March 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Seychelles, March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Sudan, March 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Sudan, March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for United Arab Emirates, March 14

CAIDA IODA graph for United Arab Emirates, March 14

The Oracle Internet Intelligence graphs below show the impact of the disruption at a network level for providers in Bangladesh (AS132602), India (AS55410), Kenya (AS33771), Mozambique (AS37342), Saudi Arabia (AS47794), and Thailand (AS38040). Measurements to these networks saw a brief period of increased latency when the disruption occurred, though as the graphs show, measurements to these networks generally shifted to go through alternative upstream providers when one was impacted.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS132692 (BSCCL), March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS55410 (Vodafone India), March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS33771 (Safaricom Limited), March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS37342 (Movitel), March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS47794 (Etihad Atheeb), March 14

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS38040 (TOT), March 14

Possible Network Issues

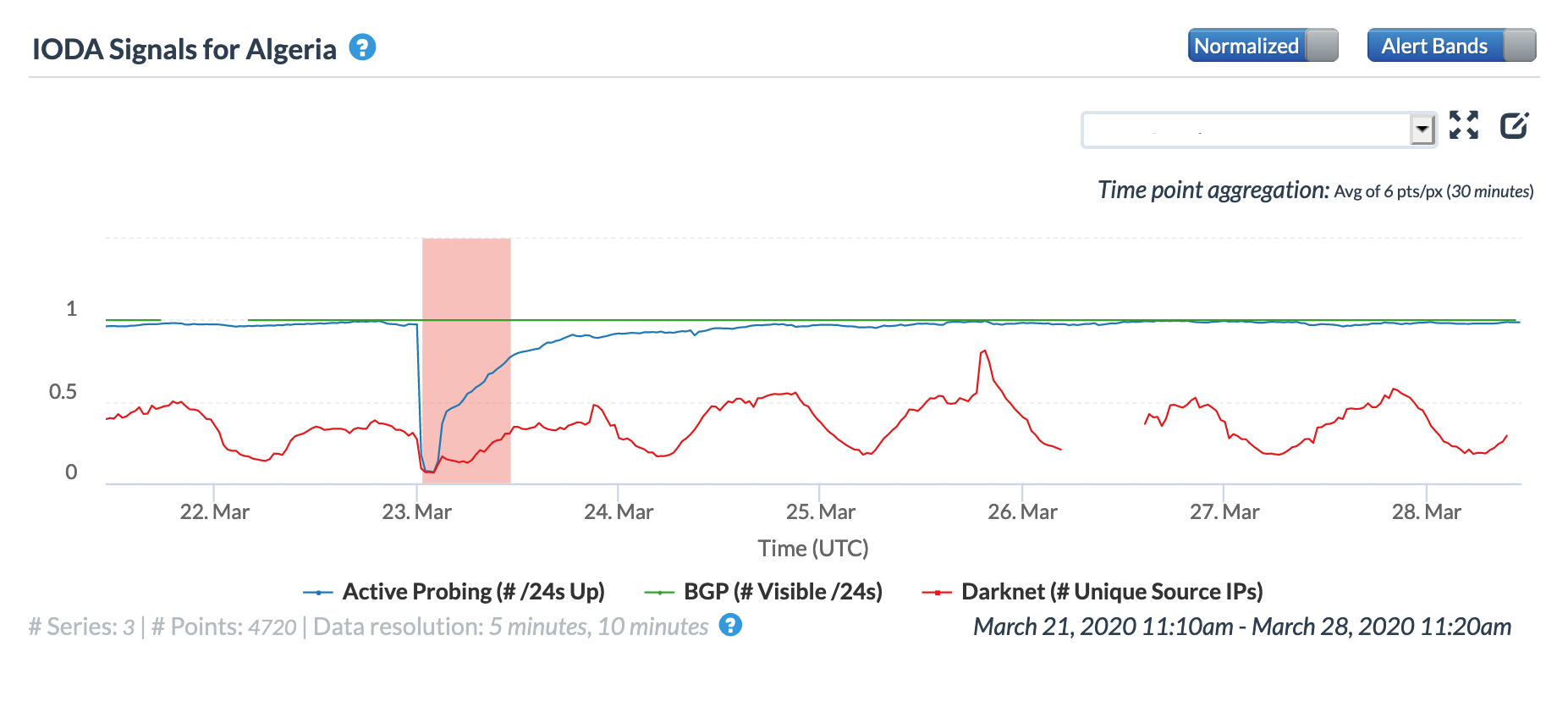

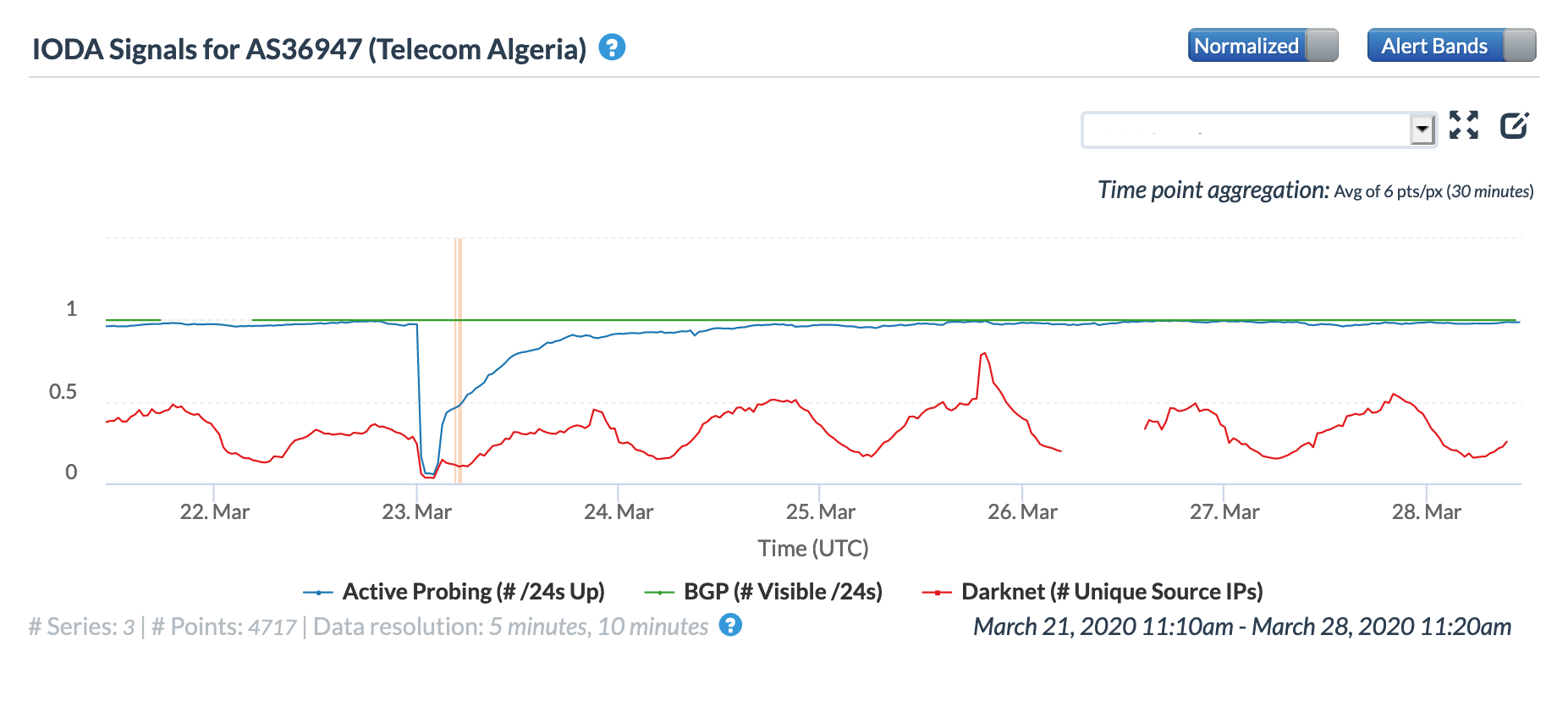

Early in the morning (GMT) of March 23, a brief but significant Internet disruption was observed in Algeria. The graphs below show that Oracle Internet Intelligence recorded a partial decline in both the active probing and BGP metrics, while CAIDA IODA saw a significant drop in the active probing metrics, but no change to the BGP metric.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Algeria, March 23

CAIDA IODA graph for Algeria, March 23

The disruption was also clearly evident in measurements of Telecom Algeria, as seen in the graphs below. Oracle Internet Intelligence testing measured a drop in the number completed traceroutes to targets within the network across multiple upstream providers, while the CAIDA IODA measurements saw a similar sharp decline in successful active probing.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS36947 (Telecom Algeria)

CAIDA IODA graph for AS36947 (Telecom Algeria)

However, there was apparently some question about the cause of the disruption, as Telecom Algeria posted a “disclaimer” to its Facebook page on March 24 that claimed (via Google Translate) “Contrary to what has been announced and reported by some media and on social networks about of a supposed shutdown of the Internet at the level national. Algeria Telecom wants to deny and reassure his kind clientele that no break is programmed.” It isn’t clear if this disclaimer refers to the disruption observed on the previous day, as the translation appear to refer to a future planned Internet shutdown, despite being posted the day after the disruption. (Checking against other online tools also results in similar translations.)

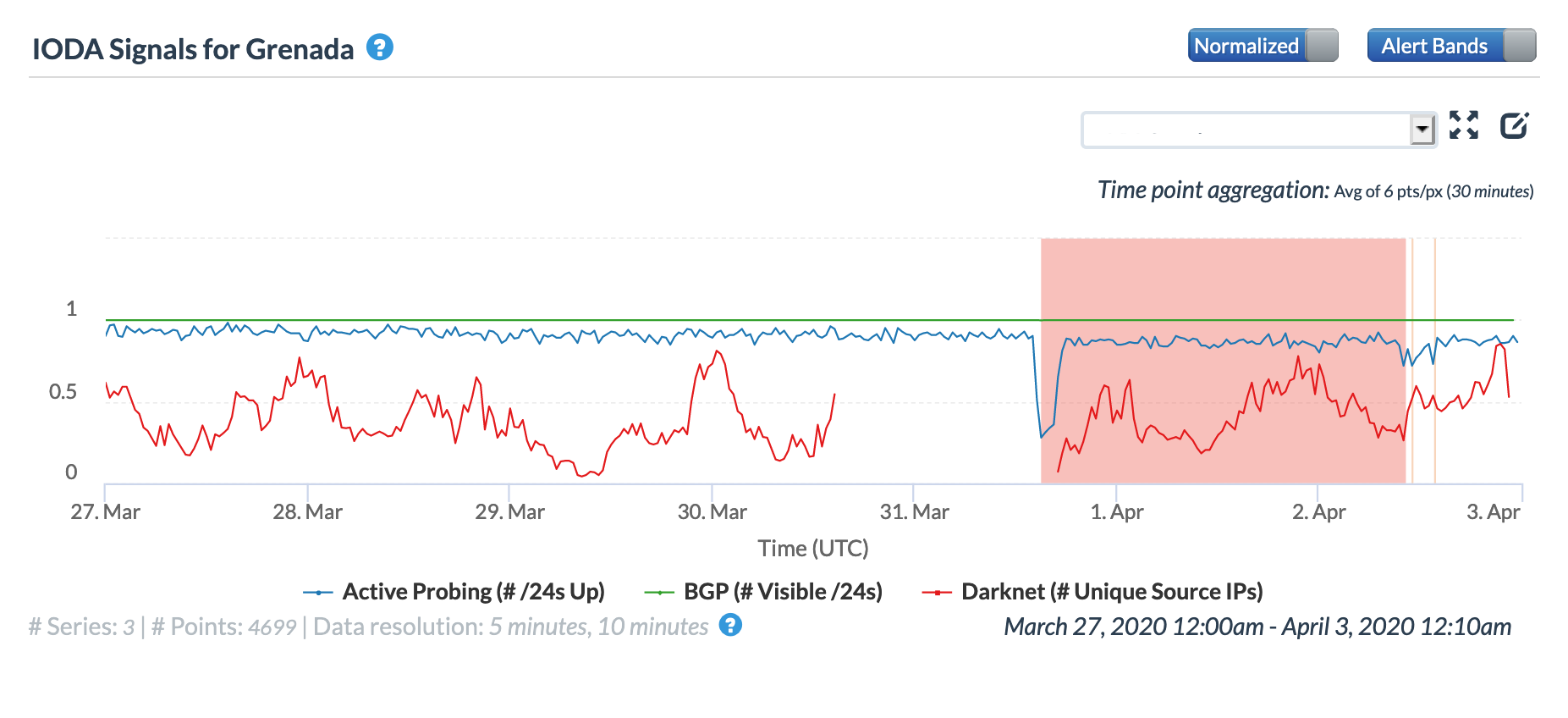

Closing out March, a brief Internet disruption was observed in Grenada on the 31st. The graphs below show that the disruption was clearly visible at both a country and network level (Columbus Communications Grenada a/k/a FLOW Grenada).

Oracle Internet Intelligence Country Statistics graph for Grenada, March 31

CAIDA IODA graph for Grenada, March 31

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS46650 (FLOW Grenada)

CAIDA IODA graph for AS46650 (FLOW Grenada)

In response to an inquiry over Facebook Messenger, FLOW Grenada explained “There was an unplanned outage that had affected our Grenada customers on March 31st. Our team had managed to have services working in less than 24 hours. We sincerely apologize for the inconvenience caused.” The provider also compensated customers with free data as an apology for the outage.

We know many of you were without service for a short period today, we are giving 1GB of data free to say thank you for your support and understanding. pic.twitter.com/AIkOSXfJfM

— Flow Grenada (@FLOWGrenada) March 31, 2020

Conclusion

As traffic volumes grew and traffic patterns shifted during March due to increased usage, many worried that the Internet would “break” and that Internet disruptions would become more significant and more frequent. As we came out of the month, it was clear that, as predicted, Internet resilience remained firmly in place. Core Internet infrastructure providers reported that while they saw increased traffic on their networks, they could easily handle it. Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) also reported record traffic growth, but they helped keep that traffic local. Well-provisioned last mile broadband networks reported increased traffic and shifting peak times, but neither caused disruptions.

However, the Internet has strained to adapt in underserved and unserved areas, where insufficient investment has been made to make high-speed broadband available and affordable. Users on these networks perceive that Internet disruptions have occurred more frequently as their connections are unable to cope with the demands of videoconferencing, streaming media, and online learning, often all concurrently competing for bandwidth. The depth of the “digital divide” became much clearer around the world in March – policy changes and directed investment are needed to deliver an Internet that is resilient for all users.

]]>Note: Previous posts have frequently differentiated between the “Traceroute Completion Ratio” metric used by Oracle Internet Intelligence and the “Active Probing” metric used by CAIDA IODA. As traceroute-based measurement is a form of active probing, posts will generally refer to both metrics as “active probing” going forward. However, references to specific metrics in a specific graph will continue to use the appropriate label.

Earthquake

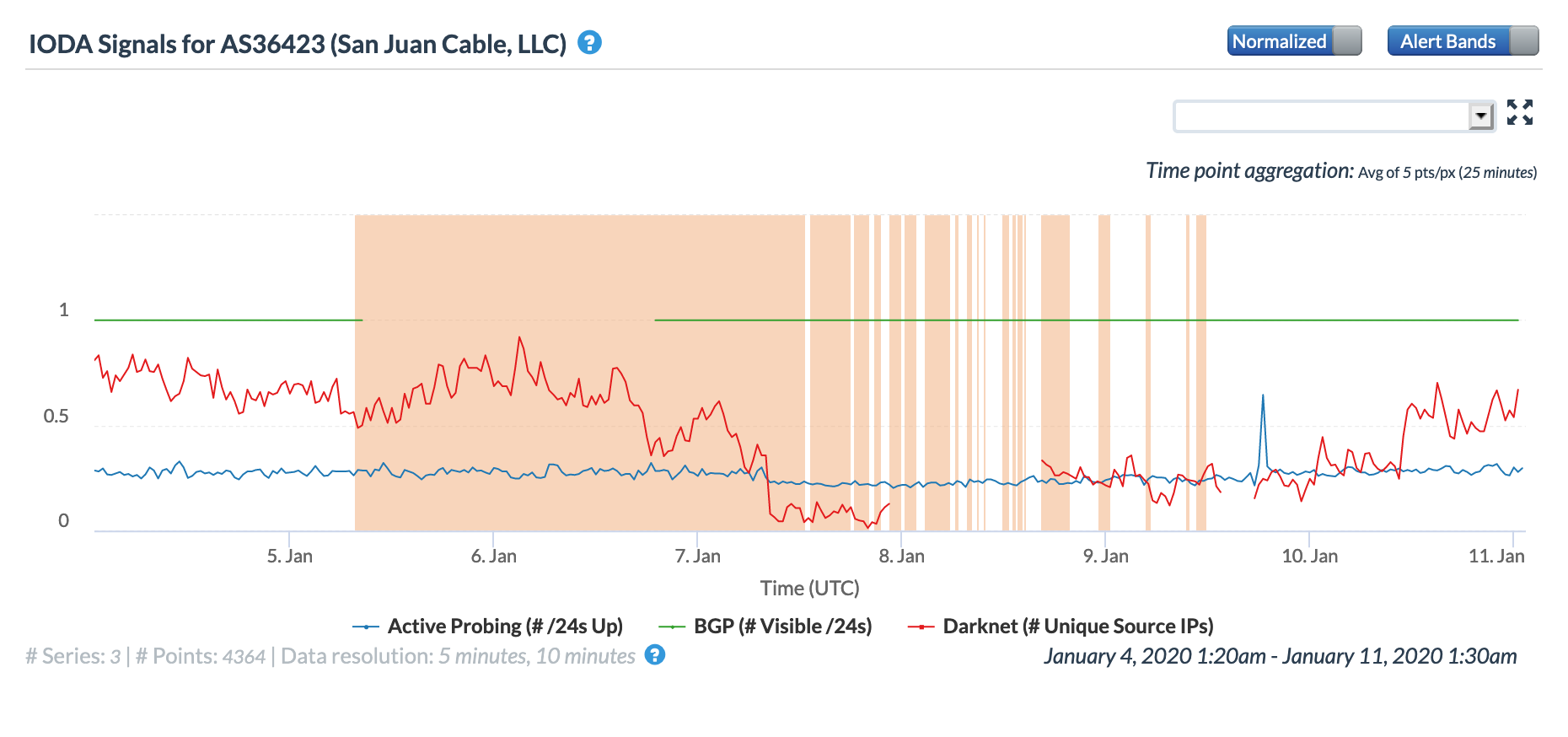

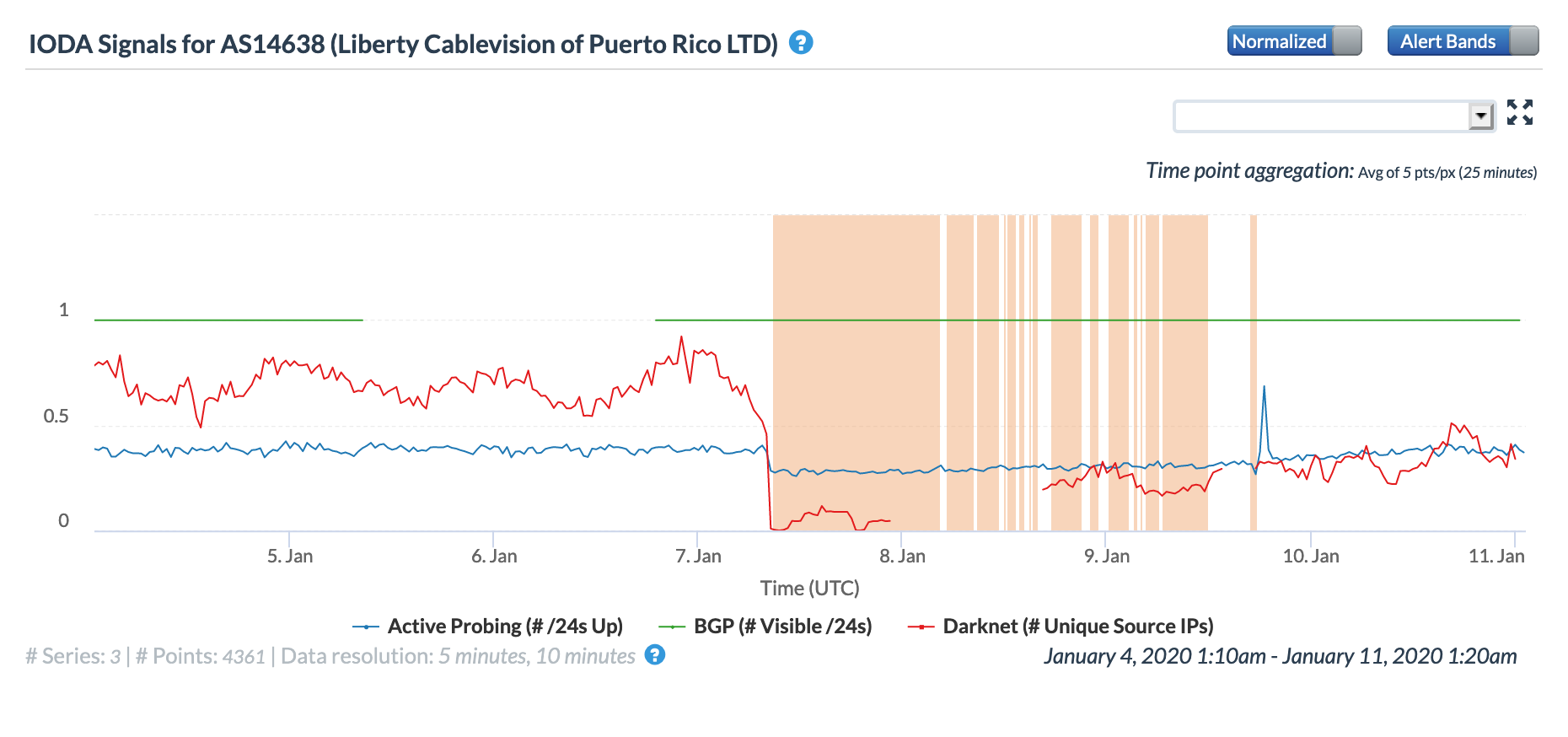

On January 7, a 6.4 magnitude earthquake struck Puerto Rico, disrupting both fixed and wireless Internet connectivity in the territory. The impact of the earthquake at a country level can be seen in the Oracle Internet Intelligence, CAIDA IODA, and Google Transparency Report graphs below. While the BGP metric remains effectively unchanged, the active probing metrics show a nominal drop at the time the earthquake occurs, with a gradual recovery over the next several days. The traffic-related metrics exhibit a more significant drop, with a similar recovery pattern. These observations are consistent with what is frequently seen in these scenarios, as earthquakes often cause widespread power outages. Because key infrastructure, including the routers making BGP announcements, is likely to be in data centers with backup power sources, the BGP metrics will see little change while power failures take active probing targets and end-user systems offline.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Puerto Rico, January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for Puerto Rico, January 7-10

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Puerto Rico, January 7-10

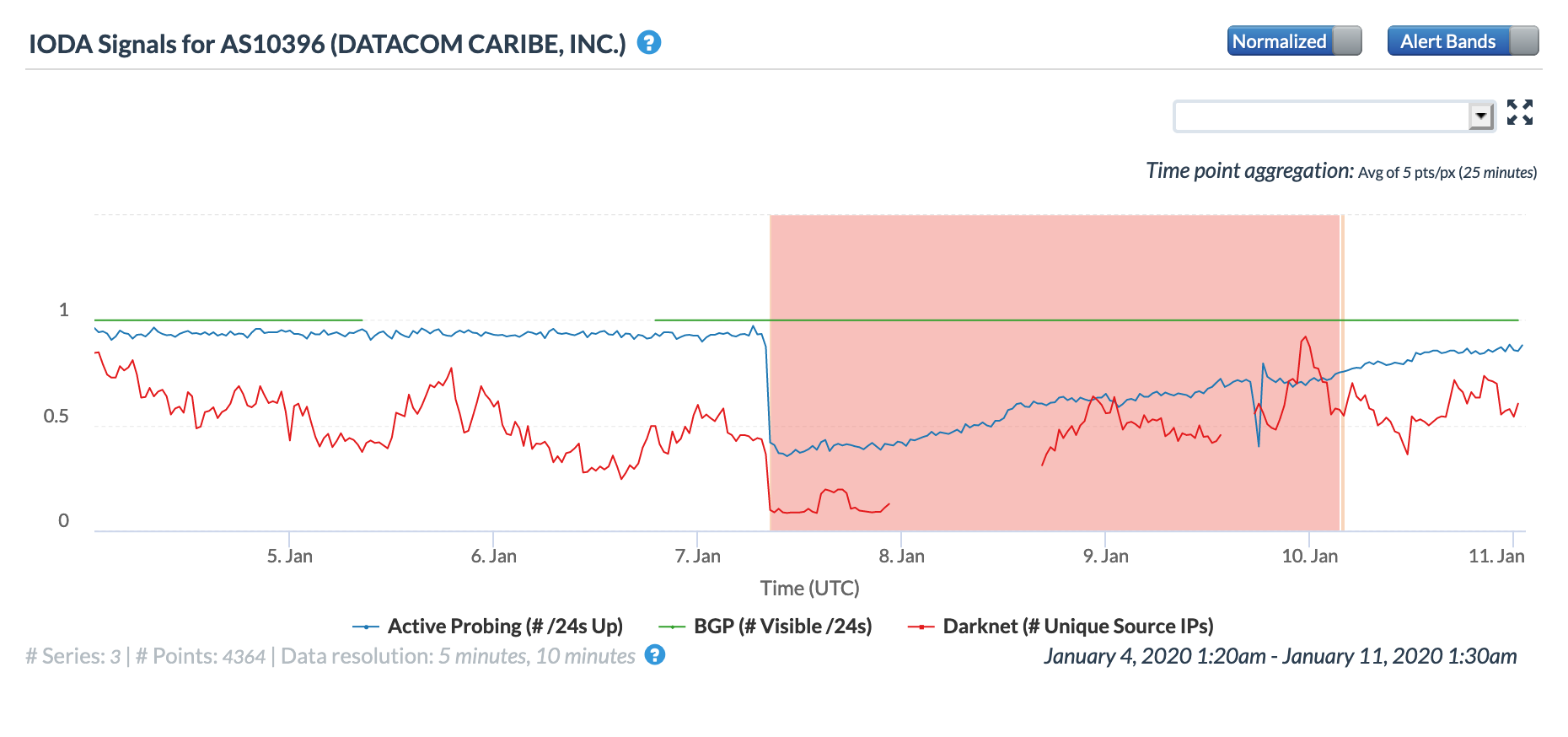

The figures below illustrate the impact of the earthquake on three local fixed connectivity providers. The impact to active probing measurements appears to be similar across both the Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA graphs. However, it is interesting to note that the CAIDA Darknet metric shows a severe drop at the time the earthquake occurs, reflecting a significant loss of connectivity to those systems connecting to the darknet address space.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS36423 (San Juan Cable), January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for AS36423 (San Juan Cable), January 7-10

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS14636 (Liberty Cablevision), January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for AS14638 (Liberty Cablevision), January 7-10

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS10396 (Datacom Caribe), January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for AS10396 (Datacom Caribe), January 7-10

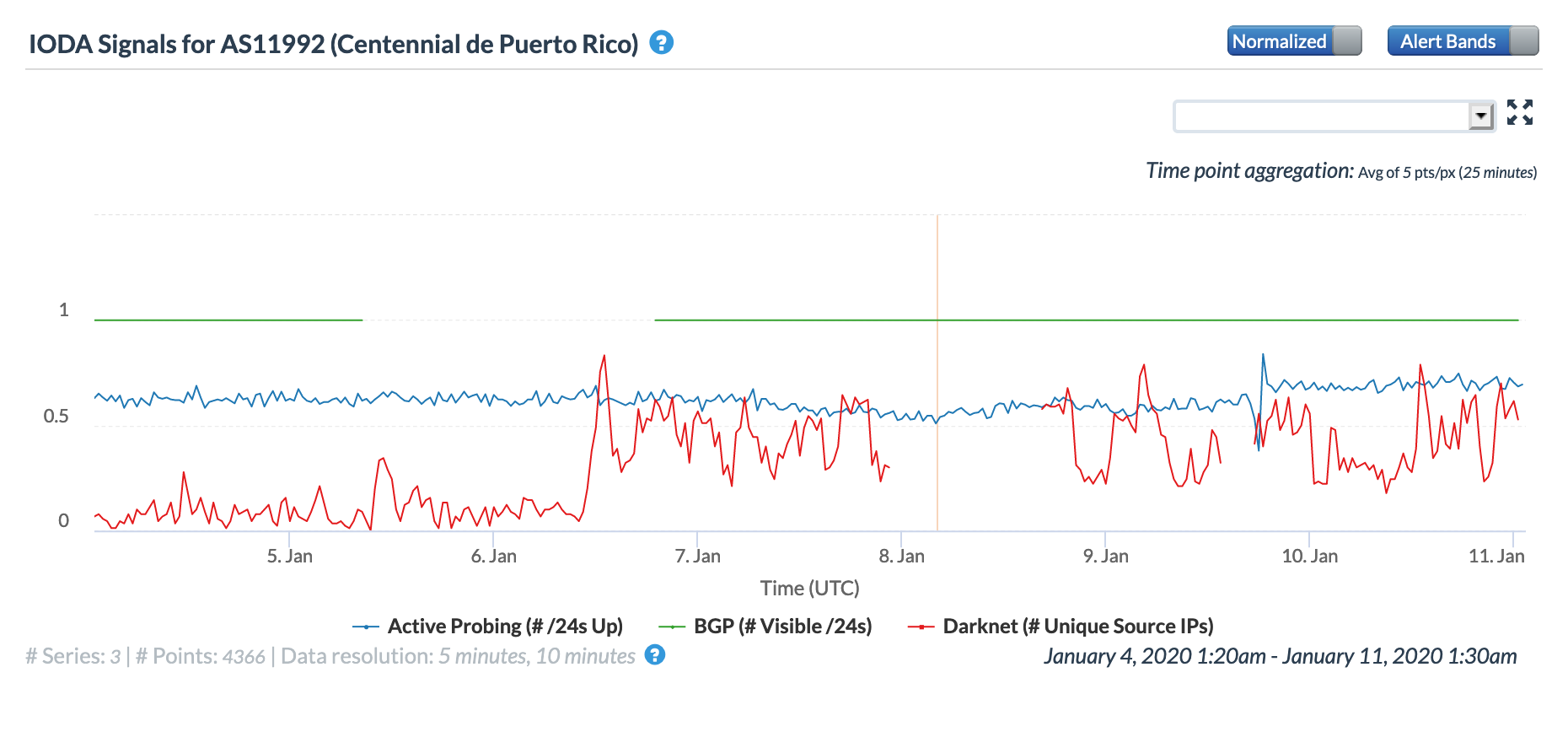

The figures below illustrate the impact of the earthquake on three local wireless connectivity providers. As would be expected, the impacts observed through these external measurements appear to be less notable than the impacts to the fixed providers. Although many mobile customers may have lost connectivity, external measurement into wireless networks is challenging due to the network architecture, leading to a more limited perspective.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS14979 (Aeronet Wireless), January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for AS14979 (Aeronet Wireless), January 7-10

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS21559 (OSNET Wireless), January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for AS21559 (OSNET Wireless), January 7-10

Oracle Internet Intelligence Traffic Shifts graph for AS11992 (AT&T Mobility), January 7-10

CAIDA IODA graph for AS11992 (AT&T Mobility), January 7-10

Power Outages

On January 18, Internet monitoring firm Netblocks Tweeted about a significant power outage impacting multiple states in Venezuela. The CAIDA IODA figures below show an Internet disruption occurring just after midnight GMT – given the time difference, this is roughly in alignment with Netblocks’ observations. The figures also show additional disruptions occurring mid-day (GMT) on January 19, as well as another one early on January 20. It isn’t known whether these additional two issues are also related to power outages, although it is likely.

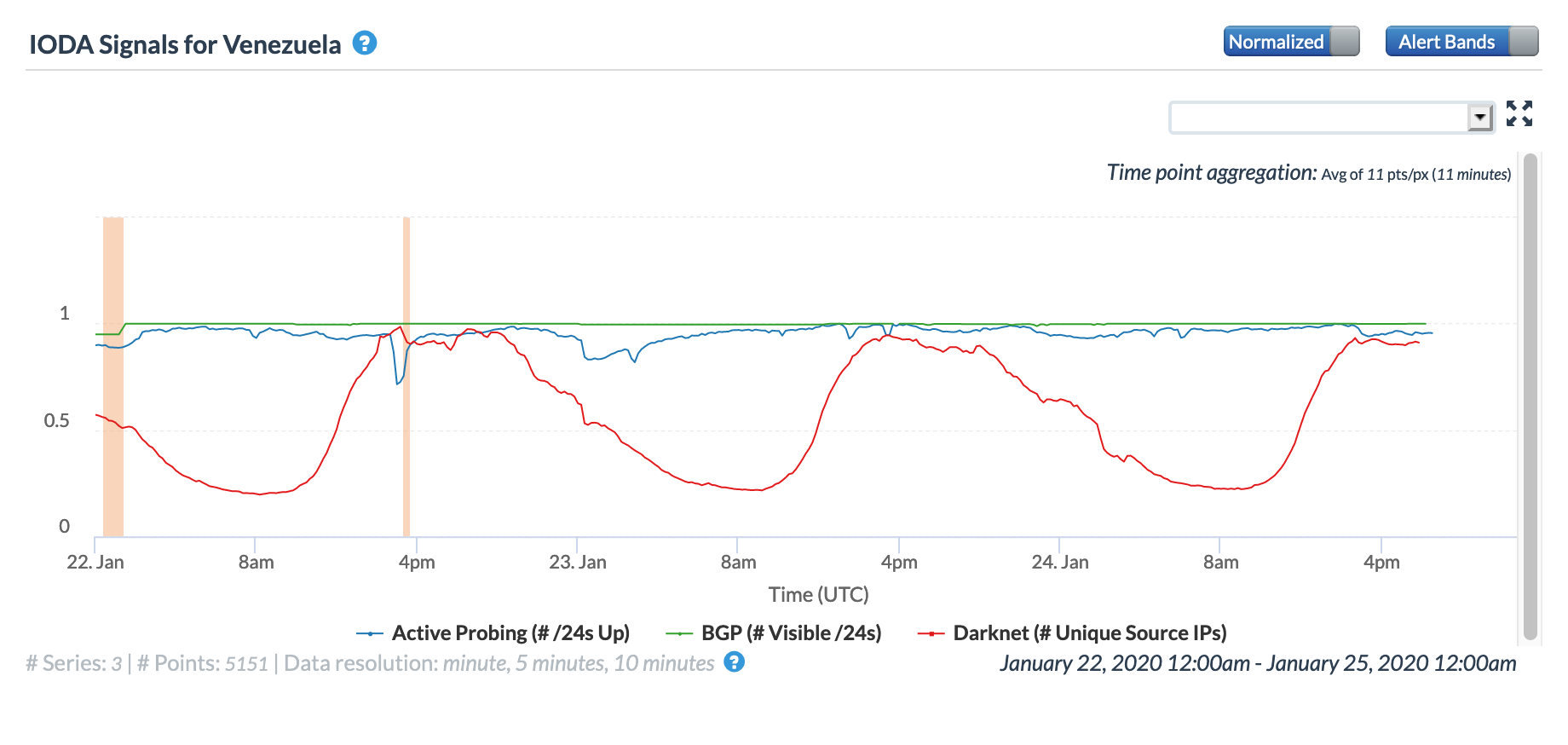

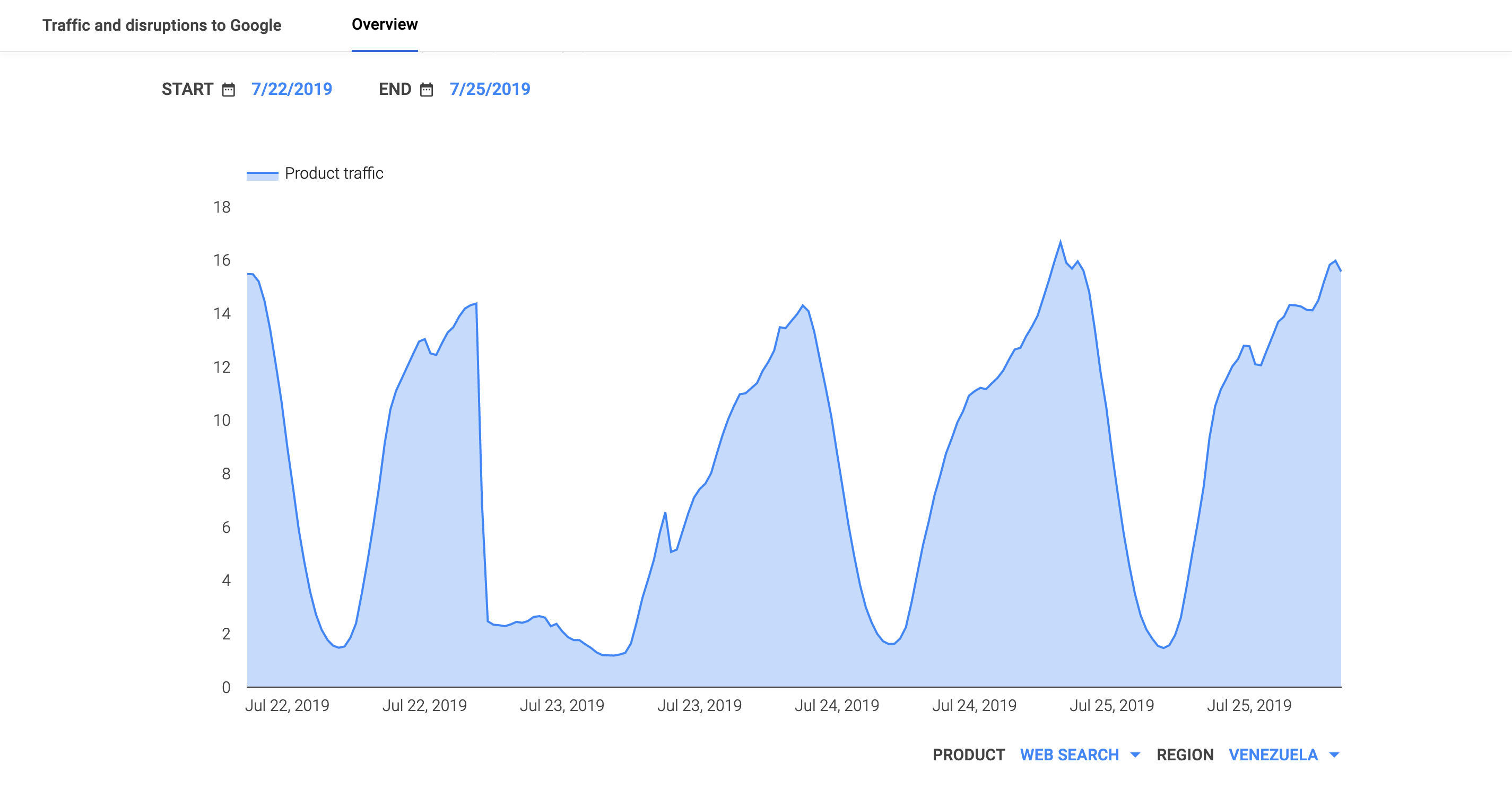

Just a few days later, on January 22, Netblocks Tweeted about another major power that knocked out Internet connectivity across multiple states in Venezuela. In the Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA graphs below, the disruption is visible as a brief drop in the active probing metric around 00:00 GMT on January 23 (again, due to the time difference).

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Statistics graph for Venezuela, January 22-23

CAIDA IODA graph for Venezuela, January 22-23

The CAIDA IODA figures below show the impact observed for five of the affected states. While the disruption is visible across all five, it appears that connectivity dropped most significantly in Mérida, Táchira, and Zulia.

Network Maintenance

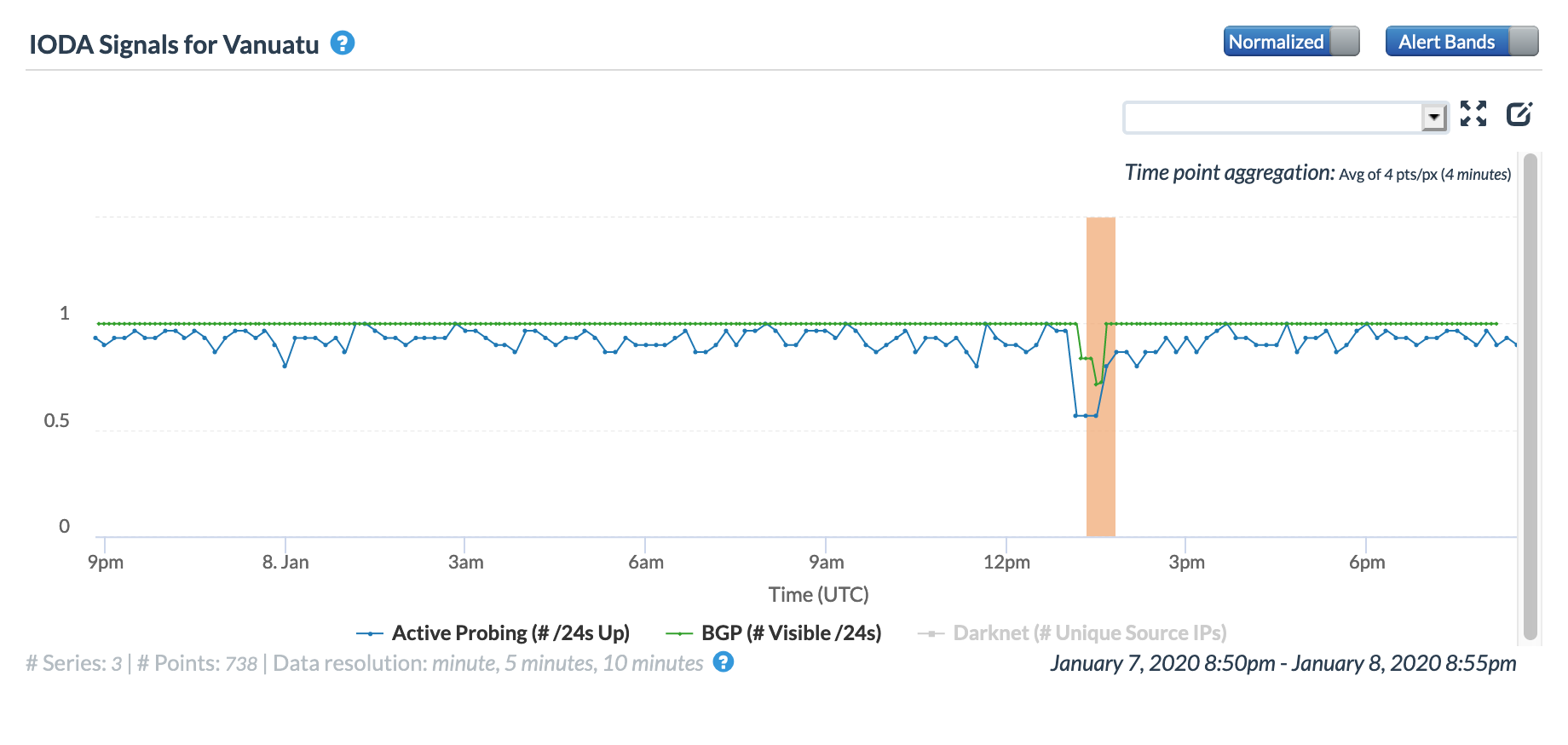

Mid-afternoon (GMT) on January 8, a brief disruption to Internet connectivity occurred on the South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu. As seen in the Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA graphs below, the disruption impacted both the active probing and BGP metrics, starting around 13:00 GMT, lasting around 45 minutes.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Vanuatu, January 8

CAIDA IODA graph for Vanuatu, January 8

Digging in further, the problem appeared to be related to a disruption at Telecom Vanuatu. According to an e-mail from a contact at the provider, the disruption was related to a planned maintenance activity on their uplink interface.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS9249 (Telecom Vanuatu), January 8

CAIDA IODA graph for AS9249 (Telecom Vanuatu), January 8

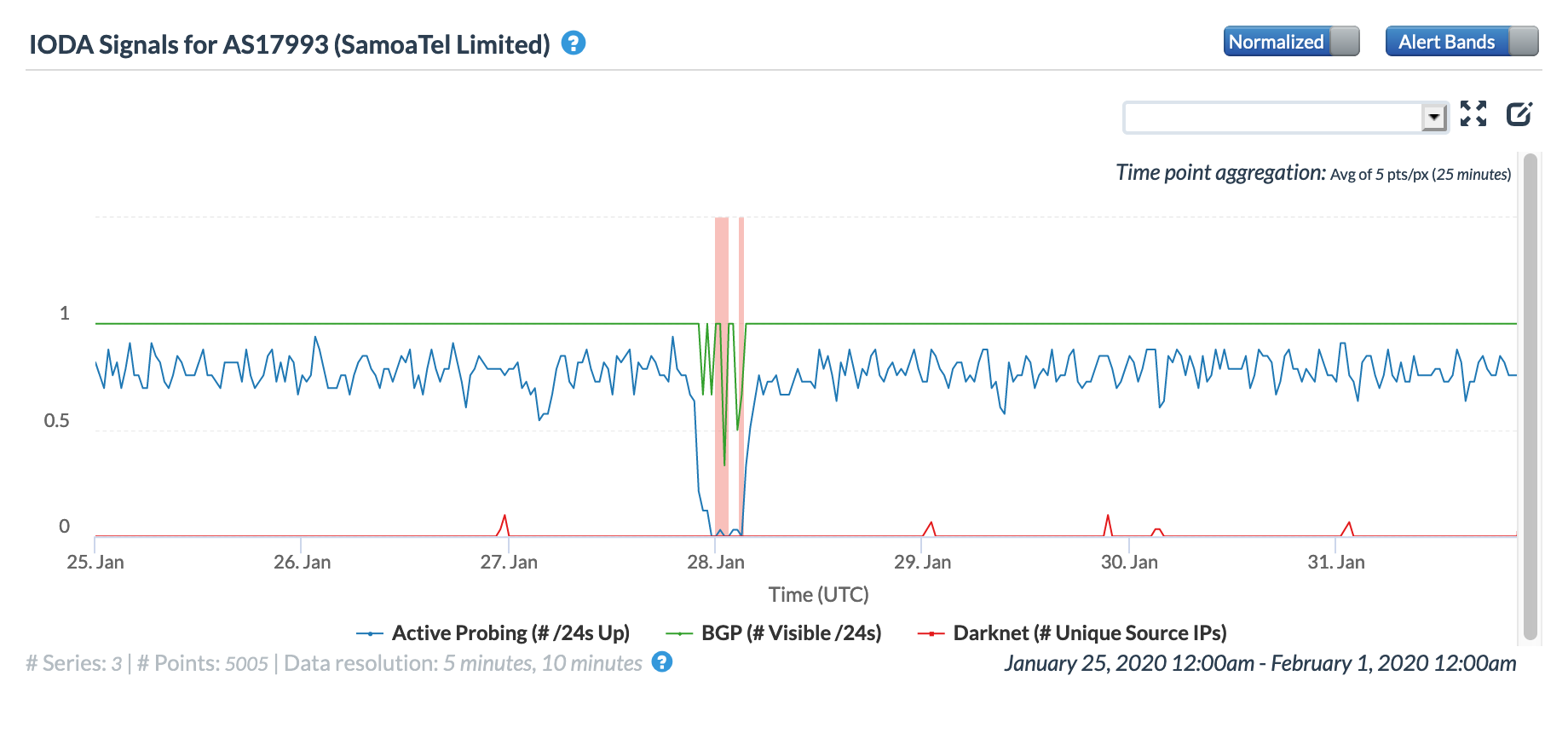

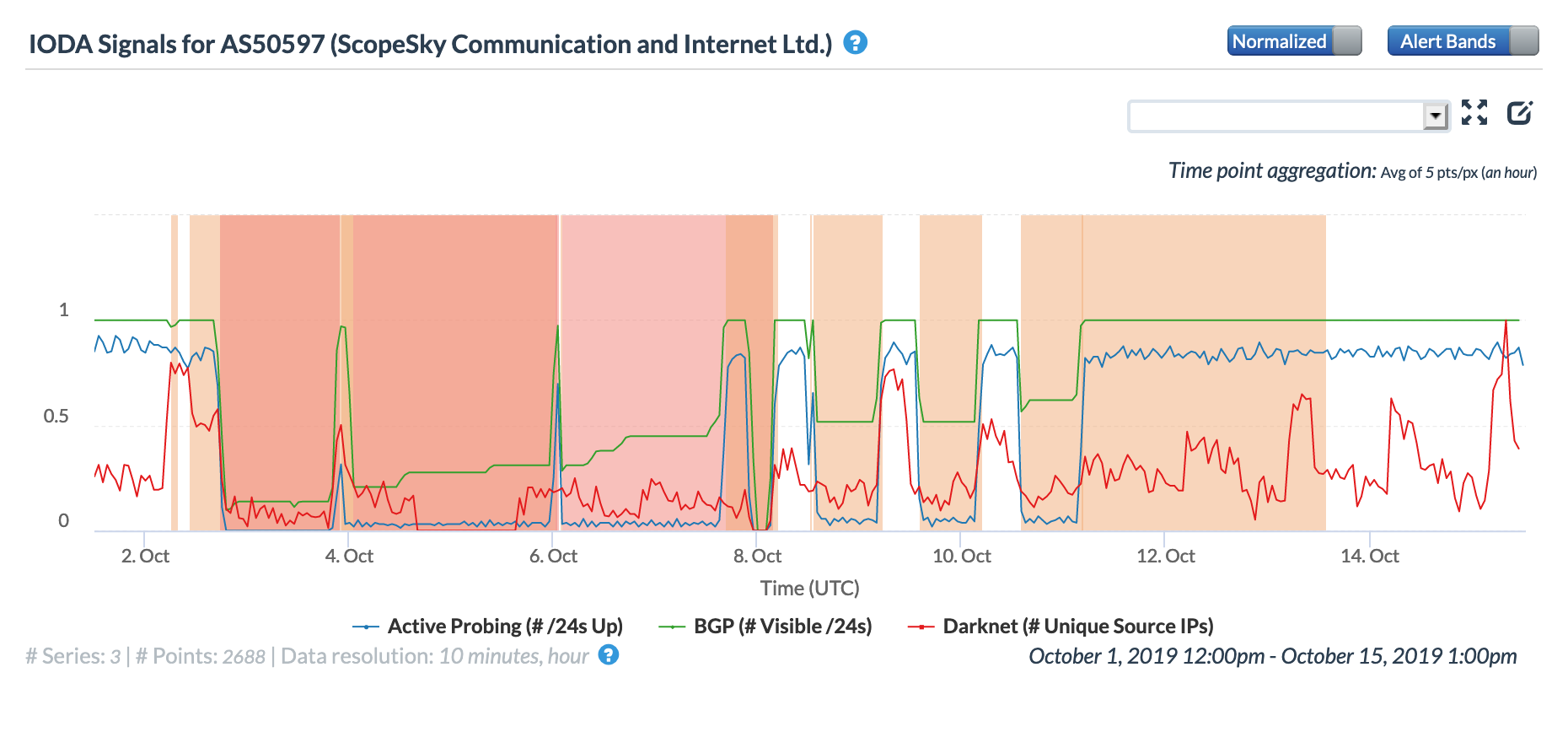

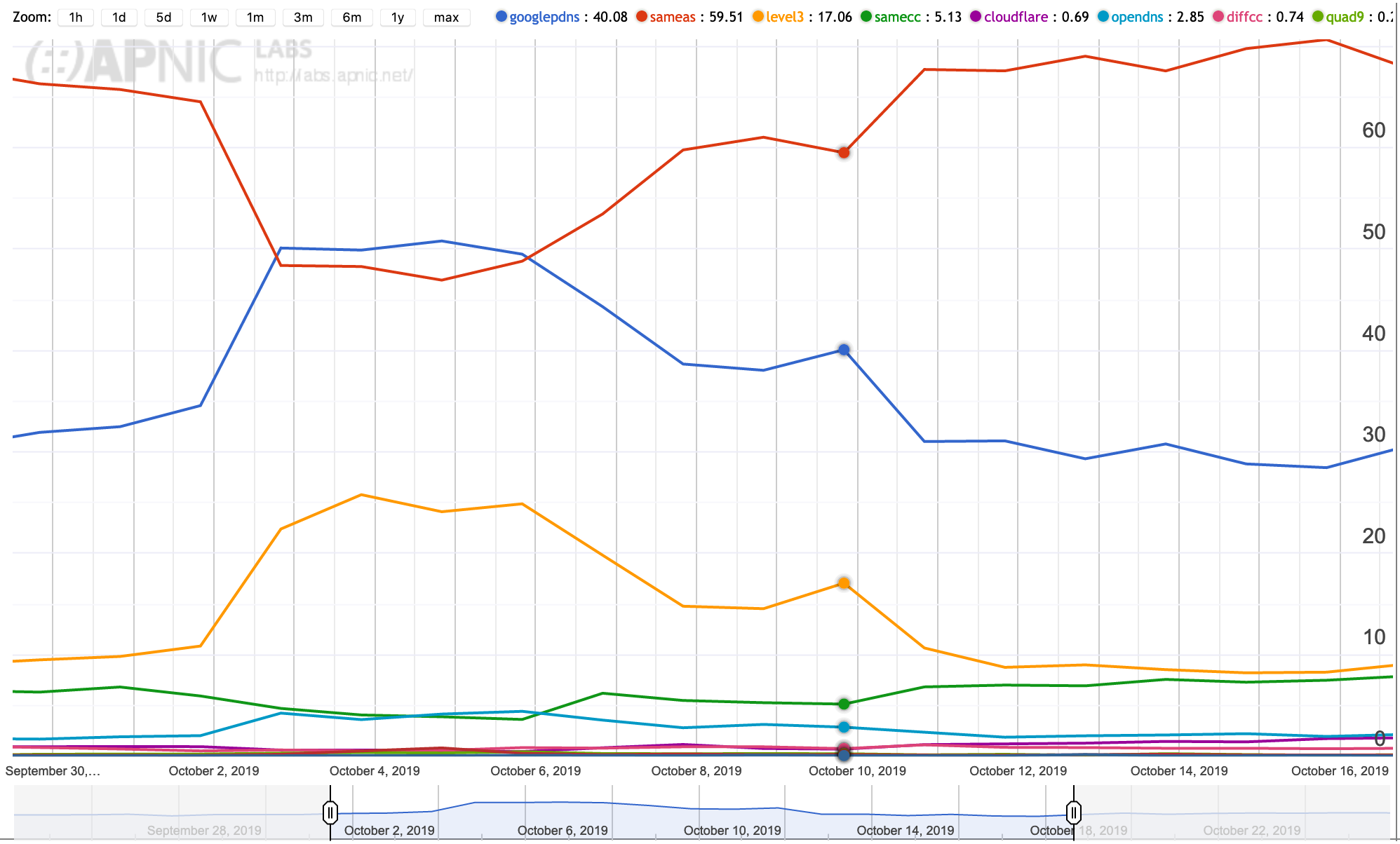

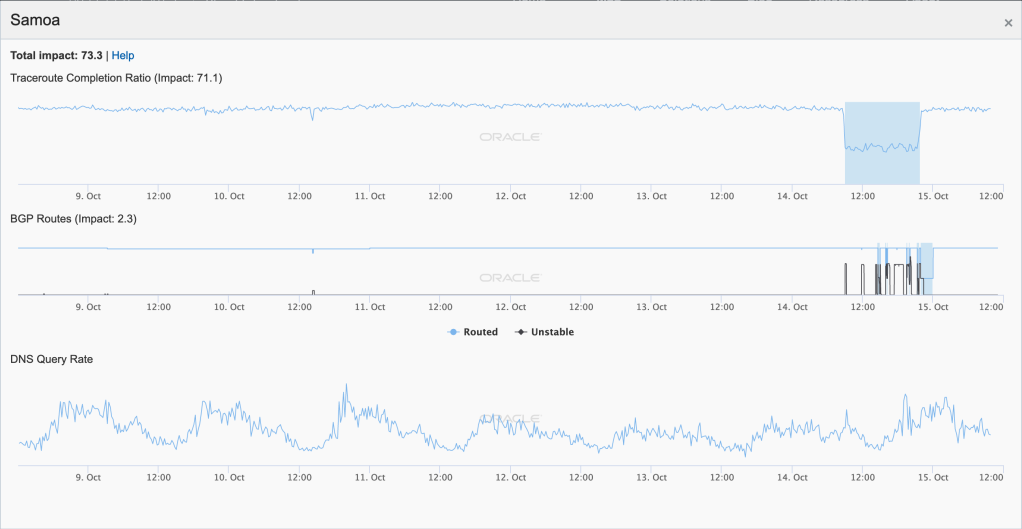

Late on January 27 into early January 28 (GMT), a significant Internet disruption was detected in Samoa. As shown in the country-level figures below, Oracle’s active probing metric dropped to about half its previous level, while CAIDA’s dropped to near zero. The BGP metric across both Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA measurements saw multiple oscillations during the period of disruption.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Samoa, January 27-28

CAIDA IODA graph for Samoa, January 27-28

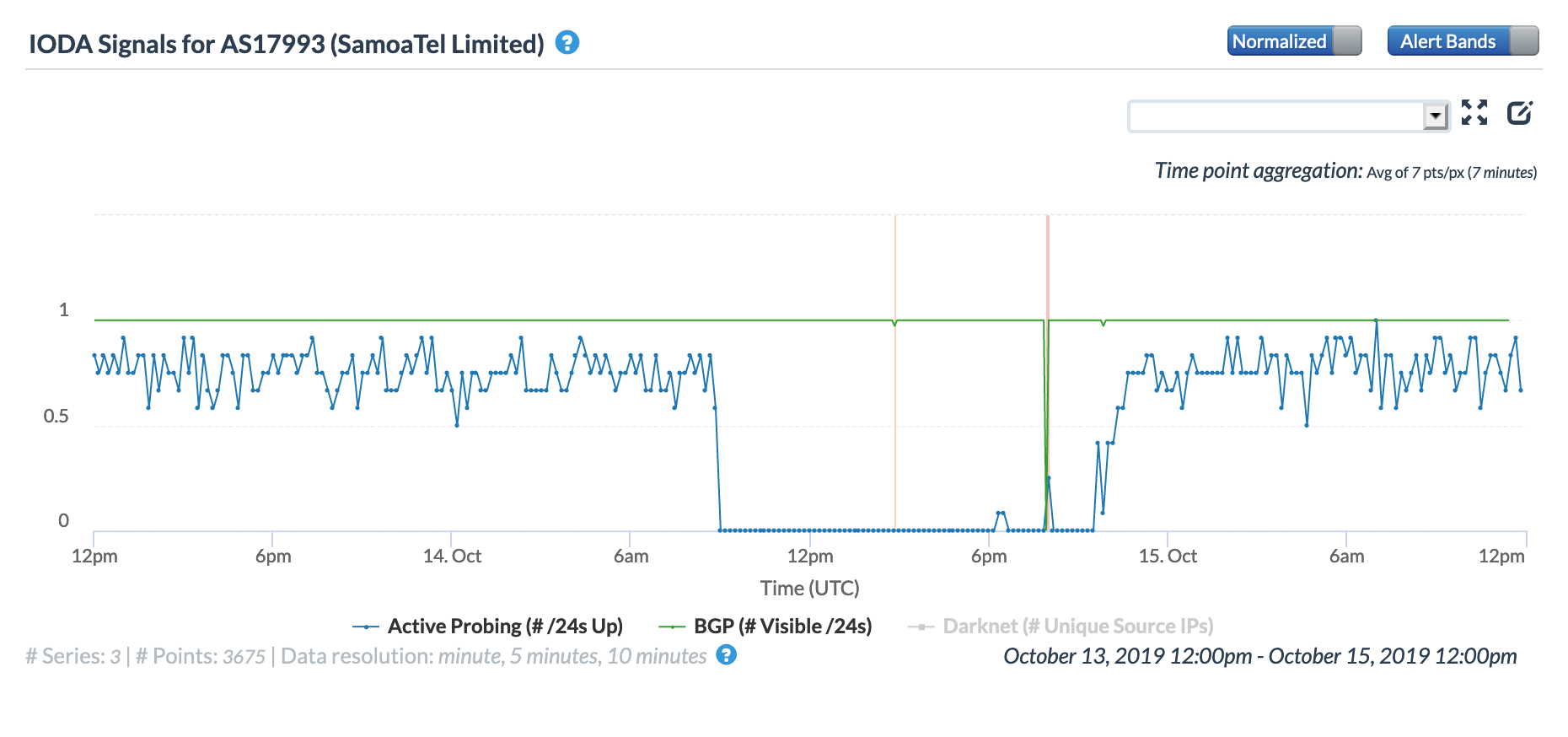

As noted in the Facebook update from Samoa Bluesky (SamoaTel) above, they experienced an issue with their “gateway”, impacting service availability. The graphs below show the impact of this issue on on Samoa Bluesky’s network. The Oracle Internet Intelligence graphs show that latency to the network spiked during the disruption, indicating that the few measurements that did complete successfully did so over a much slower path.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS17993 (SamoaTel), January 27-28

CAIDA IODA graph for AS17993 (SamoaTel), January 27-28

Government Directed

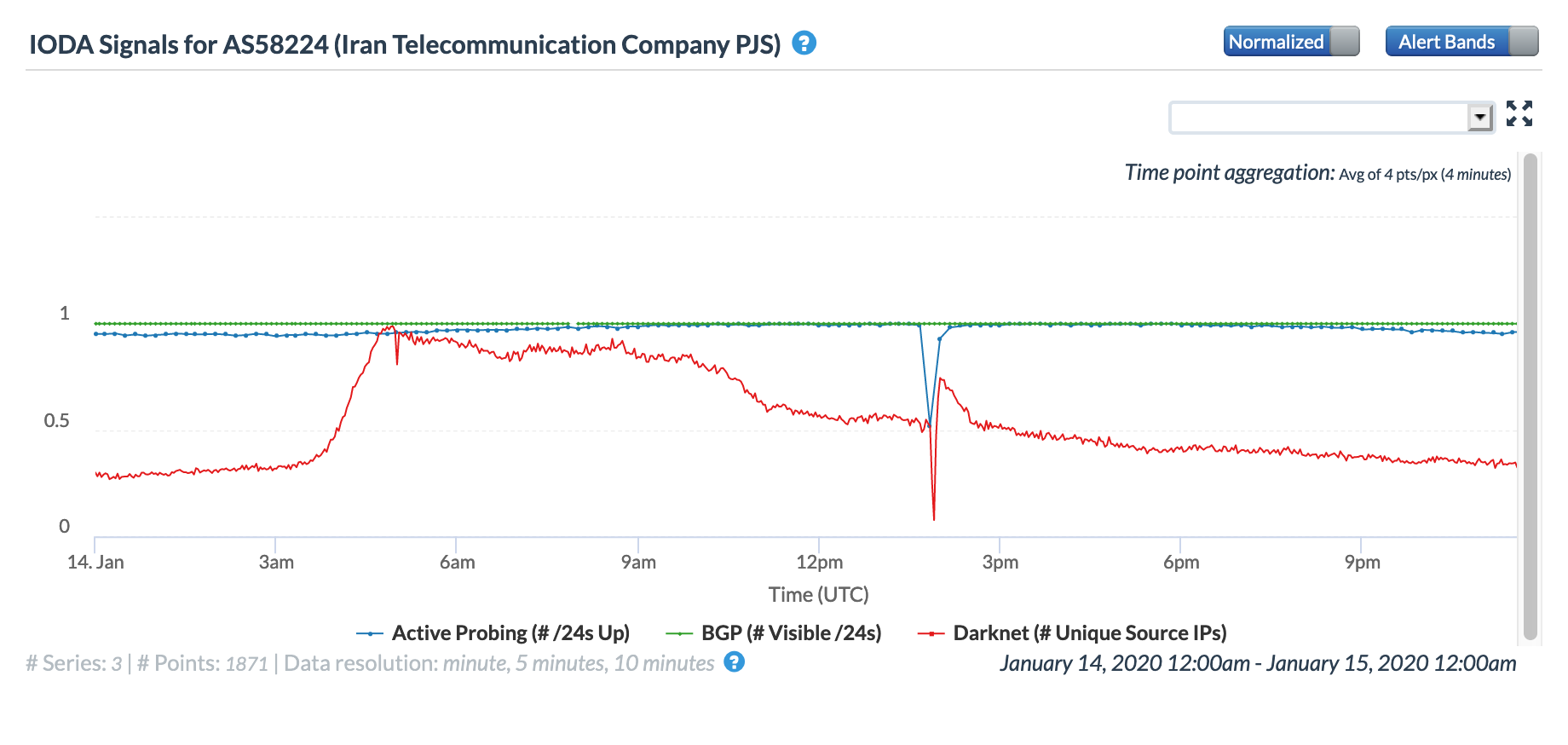

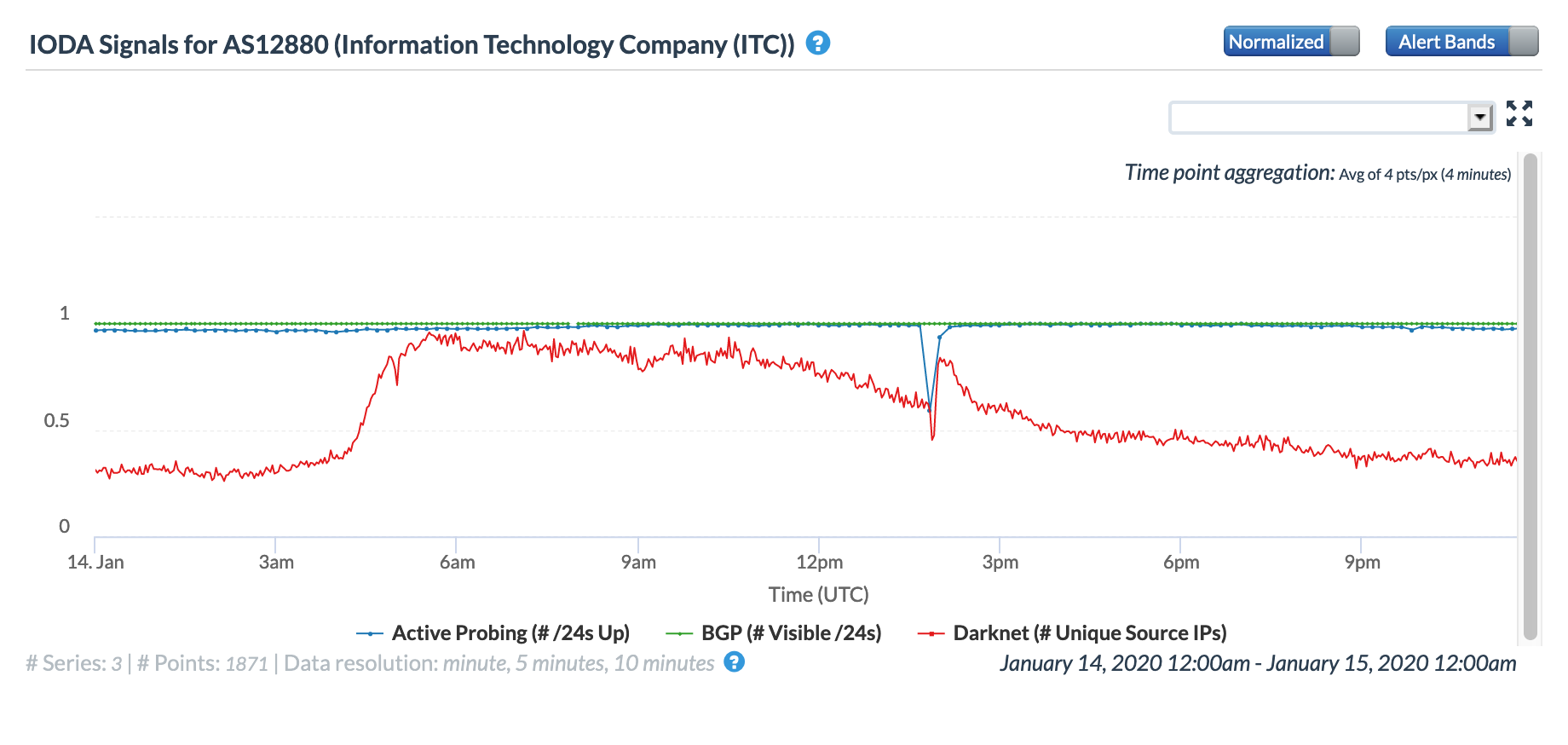

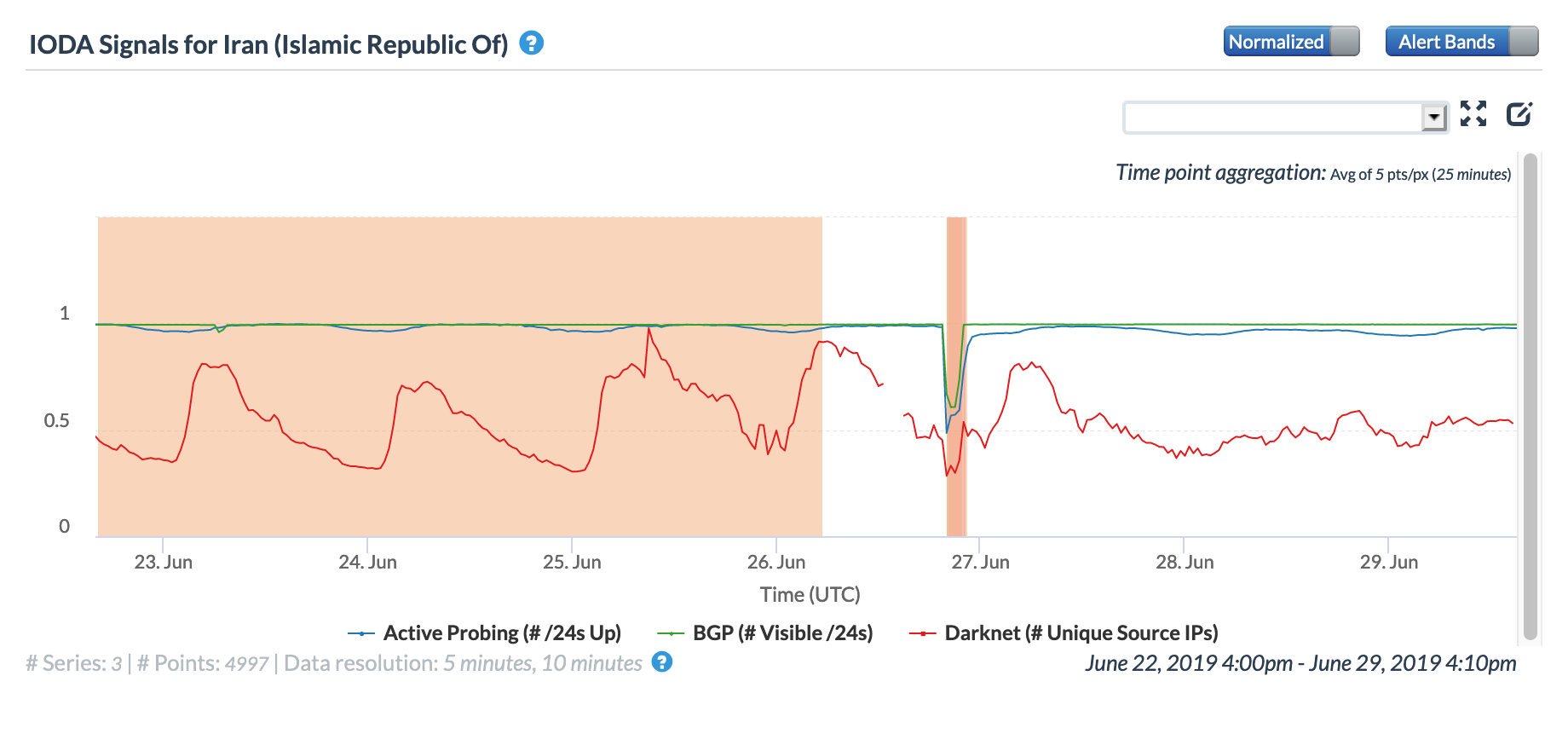

Iran is no stranger to government-directed Internet shutdowns, and in mid-January, two more occurred in response to protests for those killed on Flight PS752, the Ukraine International Airlines plane that was reportedly shot down on January 8 by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

A Tweet from Netblocks on January 13 highlighted an Internet disruption detected at Sharif University of Technology in Tehran, starting just before noon UTC, and noted that students were protesting at the university for colleagues and alumni killed on the flight. The disruption can be seen in the CAIDA IODA graph below, with both the Active Probing and Darknet metrics dropping significantly around noon. The Active Probing metric recovered after several hours, while the Darknet metric recovered to continue what was likely a diurnal decline.

A day later, another Internet disruption was observed in Iran by Netblocks and by CAIDA IODA, beginning just before 14:00 GMT. In the country-level graphs below, the disruption is most evident in the active probing metrics from both Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA, and is clear in CAIDA’s Darknet metric as well.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Iran, January 14

CAIDA IODA graph for Iran, January 14

Similar impacts can also be seen in the three CAIDA network-level graphs below, with sharp but brief declines seen in the Active Probing and Darknet metrics across three leading Iranian telecommunications firms.

CAIDA IODA graph for AS58224 (TCI), January 14

CAIDA IODA graph for AS44244 (Iran Cell), January 14

CAIDA IODA graph for AS12880 (TIC), January 14

Cable Cuts

January saw several major cable cuts that had significant and wide ranging impacts.

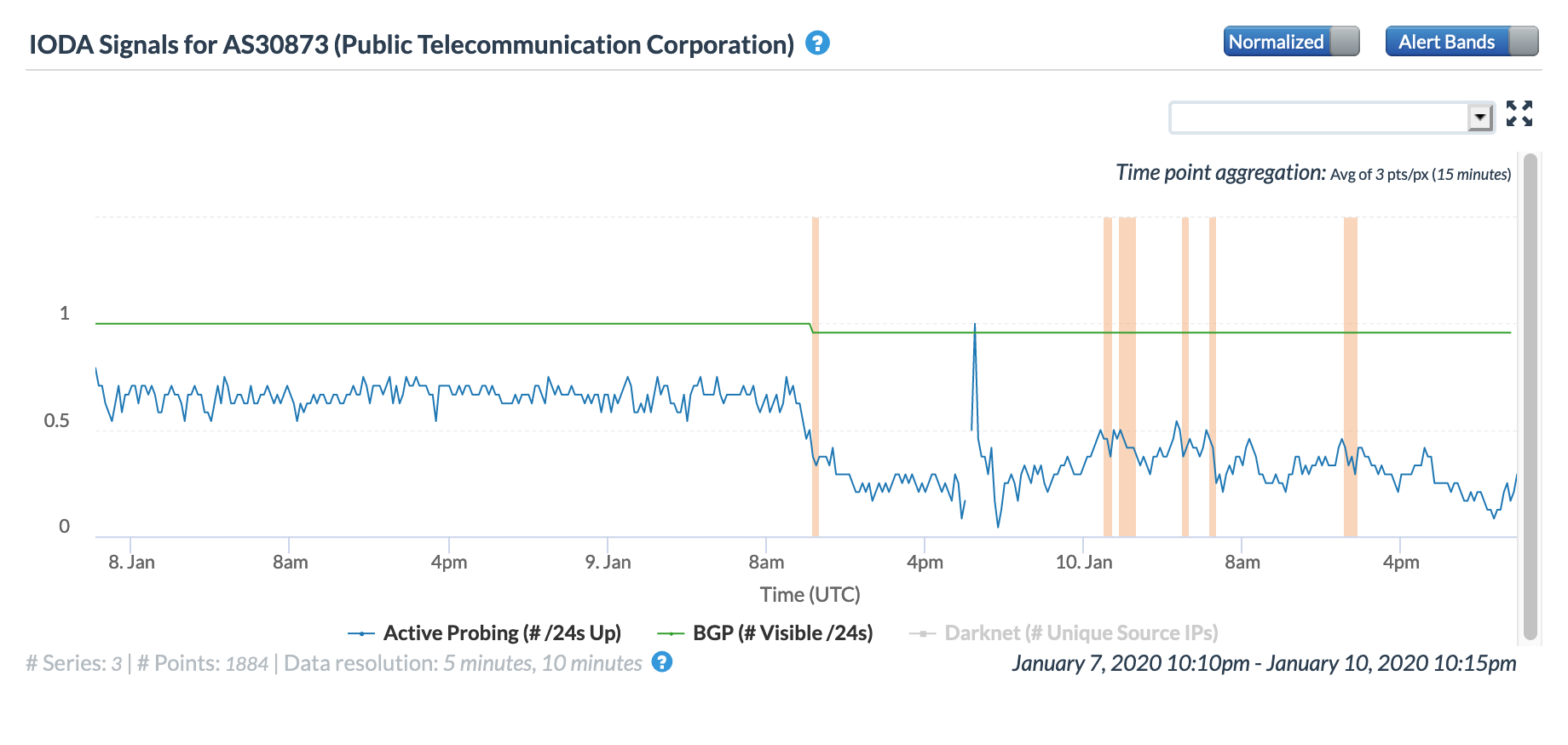

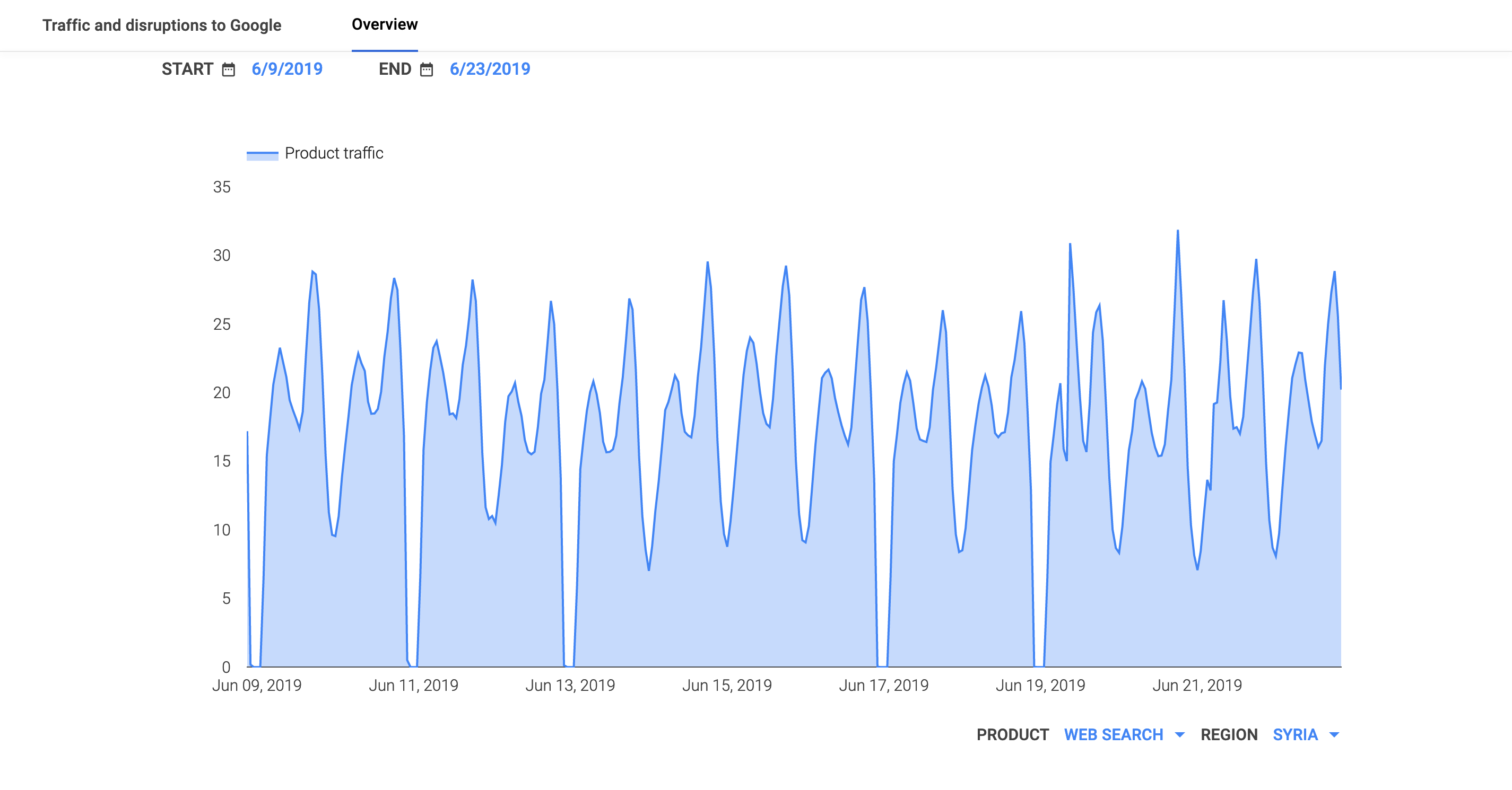

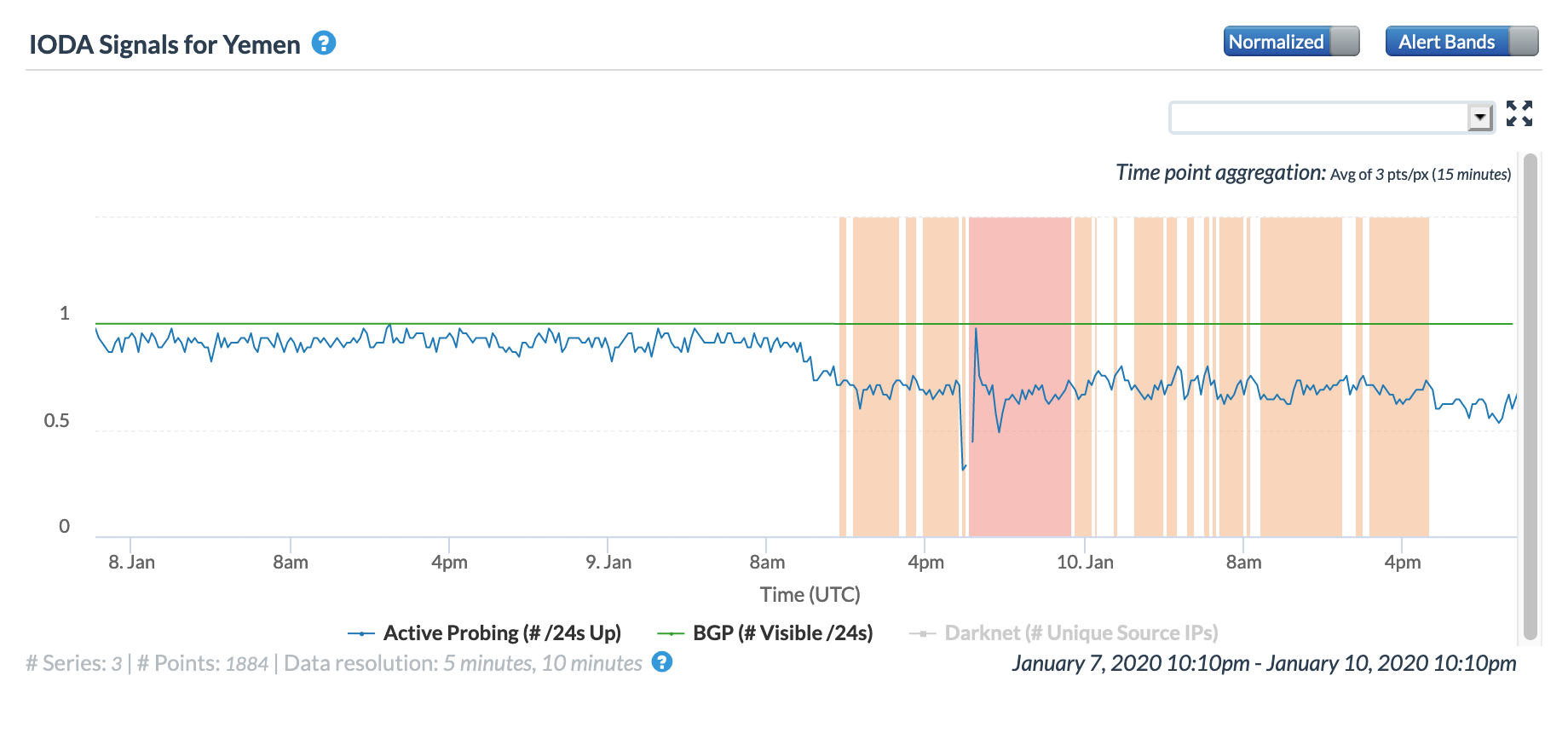

The first was observed in Yemen on January 9. In the figures below, a significant disruption can be seen in Oracle’s and CAIDA’s active probing metrics and in Google Web search traffic for Yemen around 18:00 GMT, but were preceded by a gradual decline beginning around 09:00 GMT. Initial indication that the disruption was due to a cable cut reportedly came from an SMS message from Yemen’s national Internet service provider to its users.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Tweeted confirmation of the disruption, showing the impact to YemenNet, and the provider posted the update shown below to its Facebook page, noting that the disruption was caused by a problem with the FALCON submarine cable, owned by Global Cloud Xchange. (English translation of the post via Facebook.)

More than 80 % of international internet hours in Yemen have been released as a result of an international cable outage outside Yemen

Sana ‘ a January 2020, 9 (Spa)-General announced that more than 80 % of international internet hours in Yemen were out of service as a result of an international cable outage outside Yemen.

The responsible source of the company and company of the Yemeni news agency / spa explained that a large number of internet links were out of service due to the exposure of the sea cable falcon in Suez, causing more than 80 percent of internet hours International in Yemen.

The source explained that there are ongoing efforts to follow up on cable repair and return of service soon.

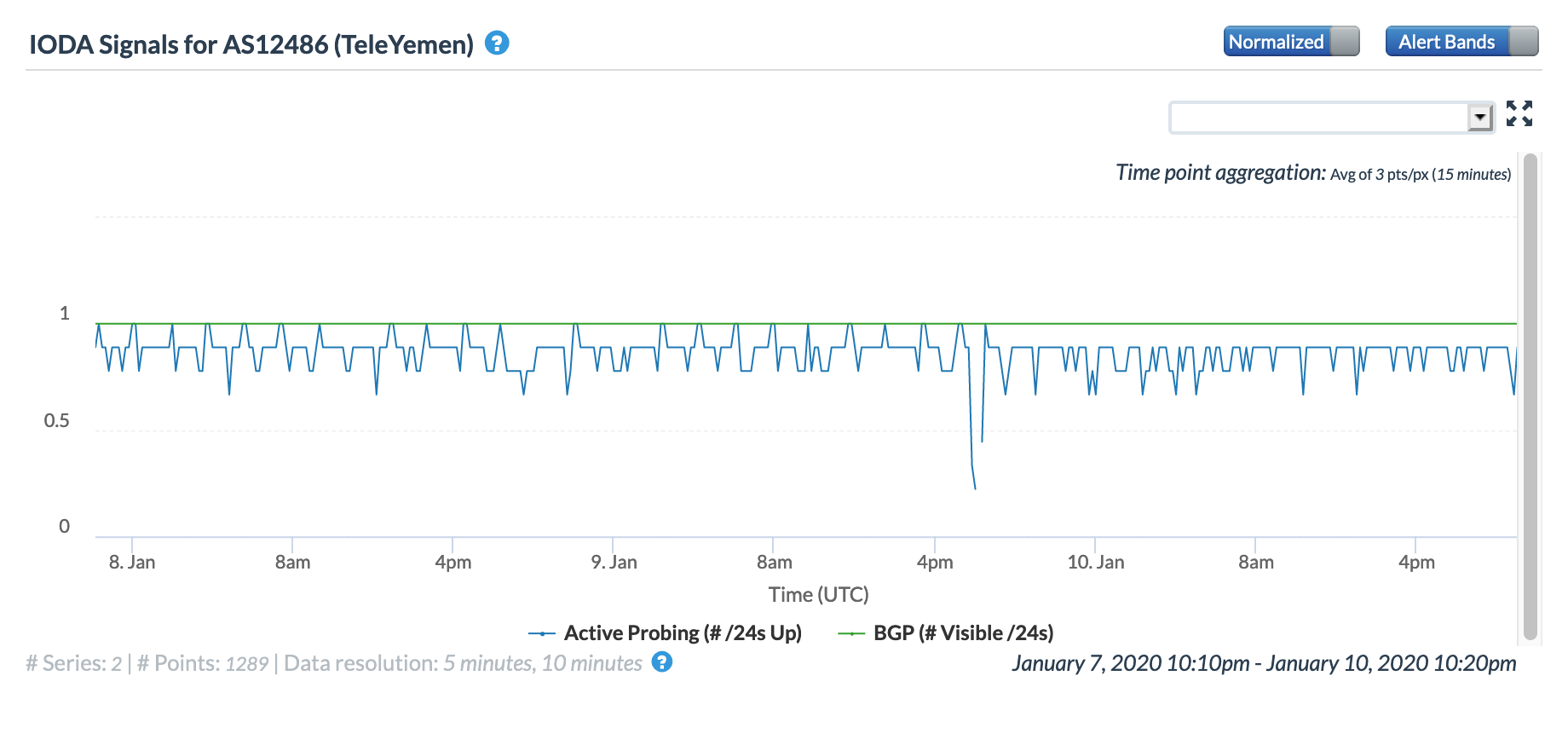

The figures below show the impact on two of YemenNet’s autonomous systems, with the disruption affecting connectivity to AS30873 significantly more than AS12486. The Oracle Internet Intelligence graphs show that when the cable cut occurred and upstream connectivity to AS15412 (Global Cloud Xchange) was lost, YemenNet was able to quickly fail over to backup/alternate upstream providers

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS30873 (YemenNet) , January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS30873 (YemenNet), January 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS12486 (YemenNet) , January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS12486 (YemenNet), January 9

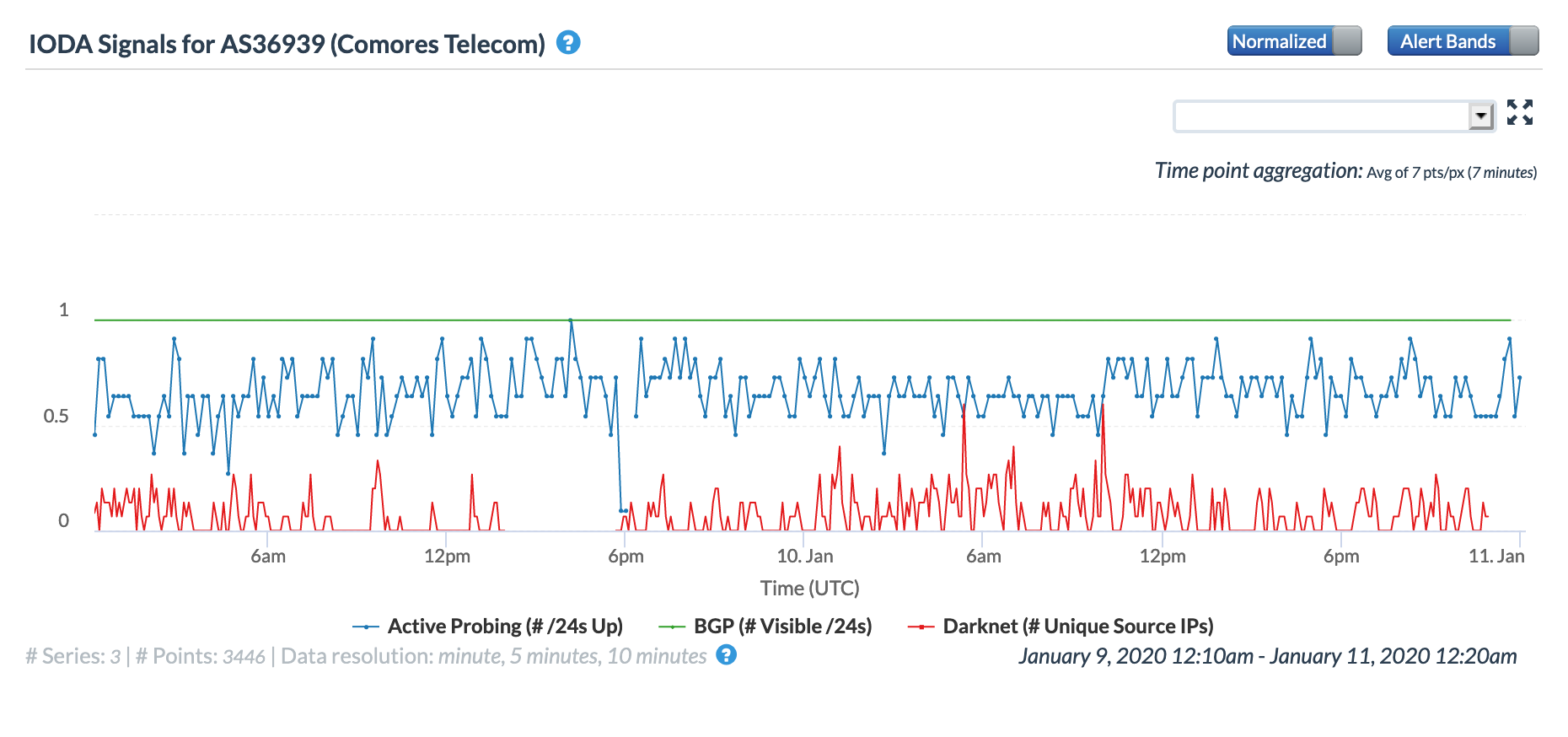

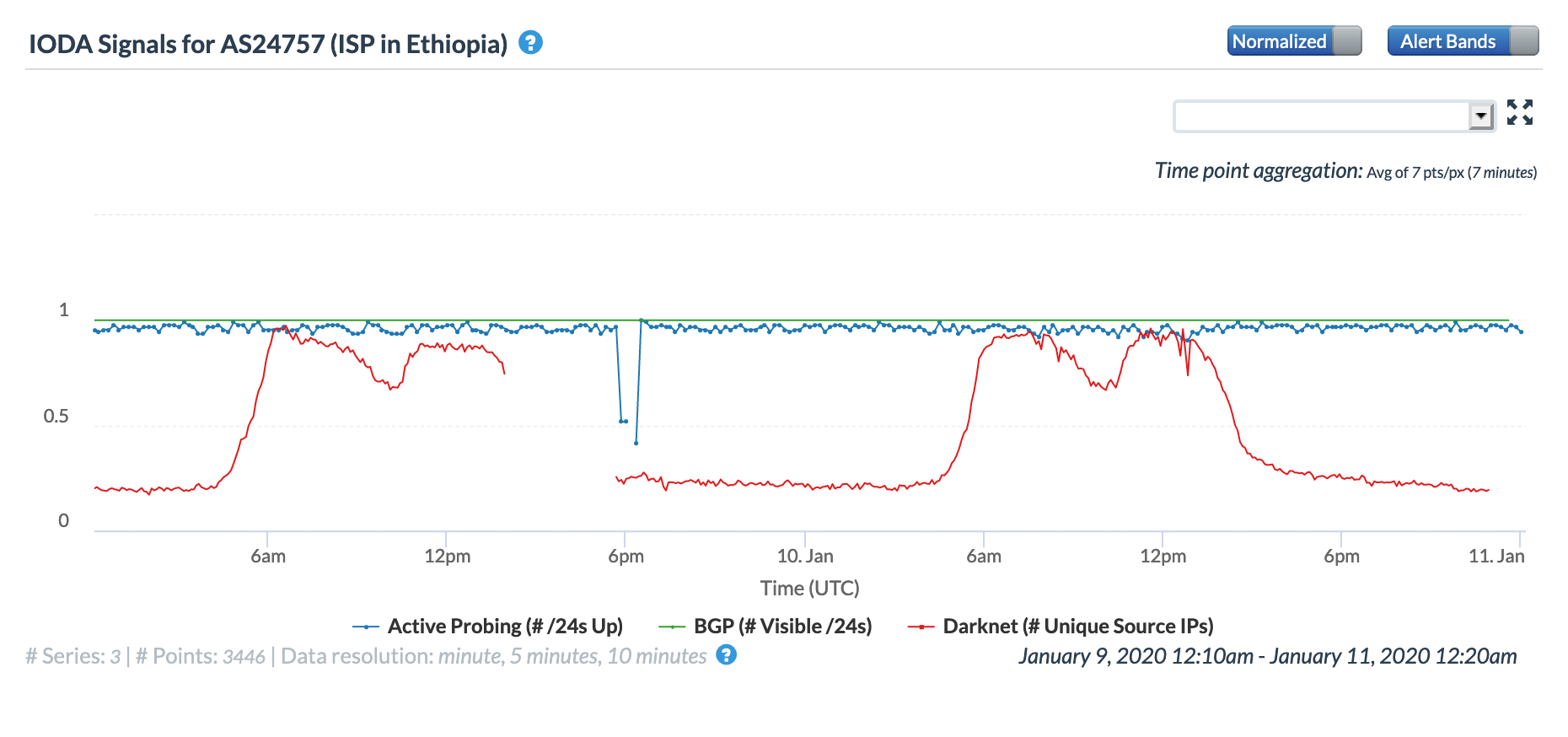

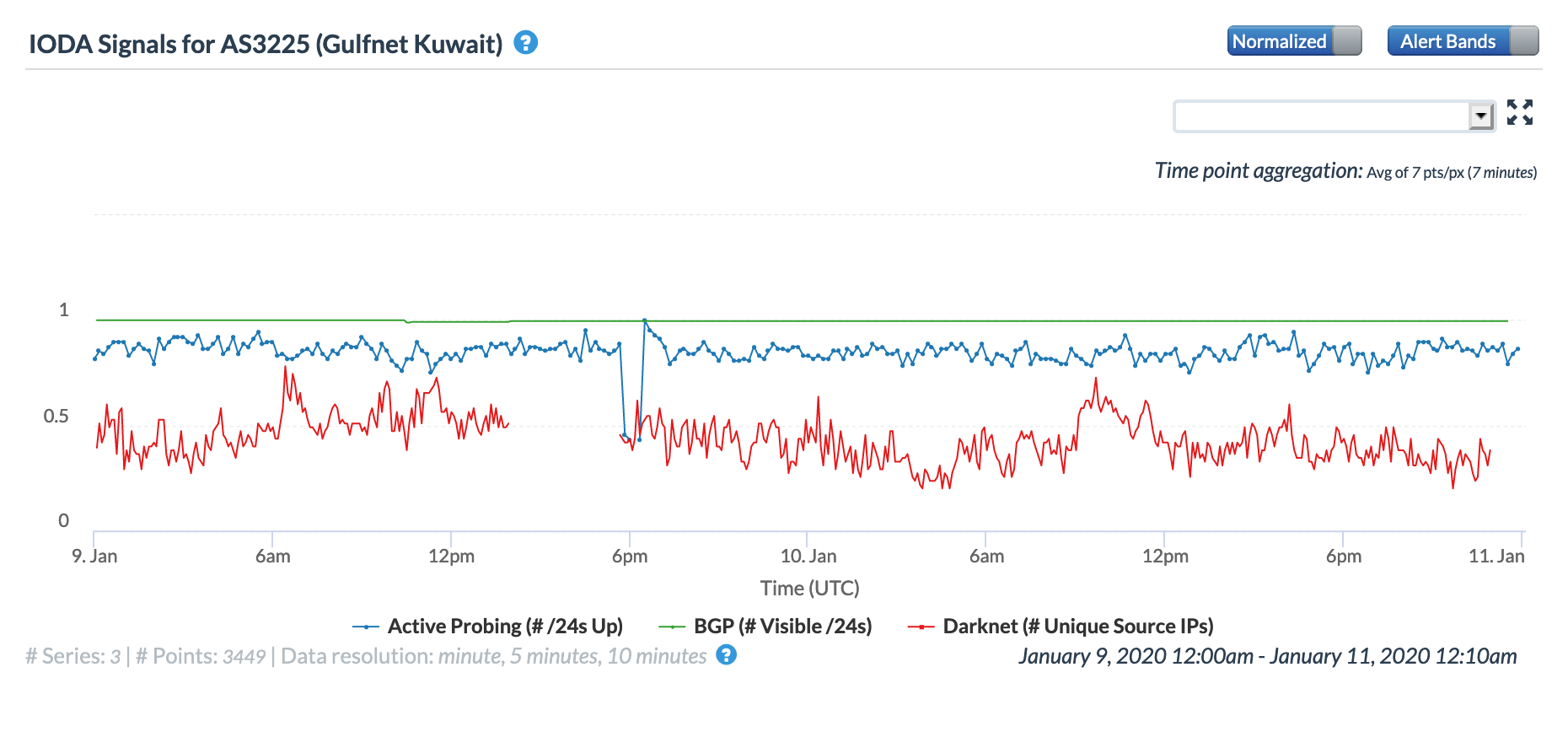

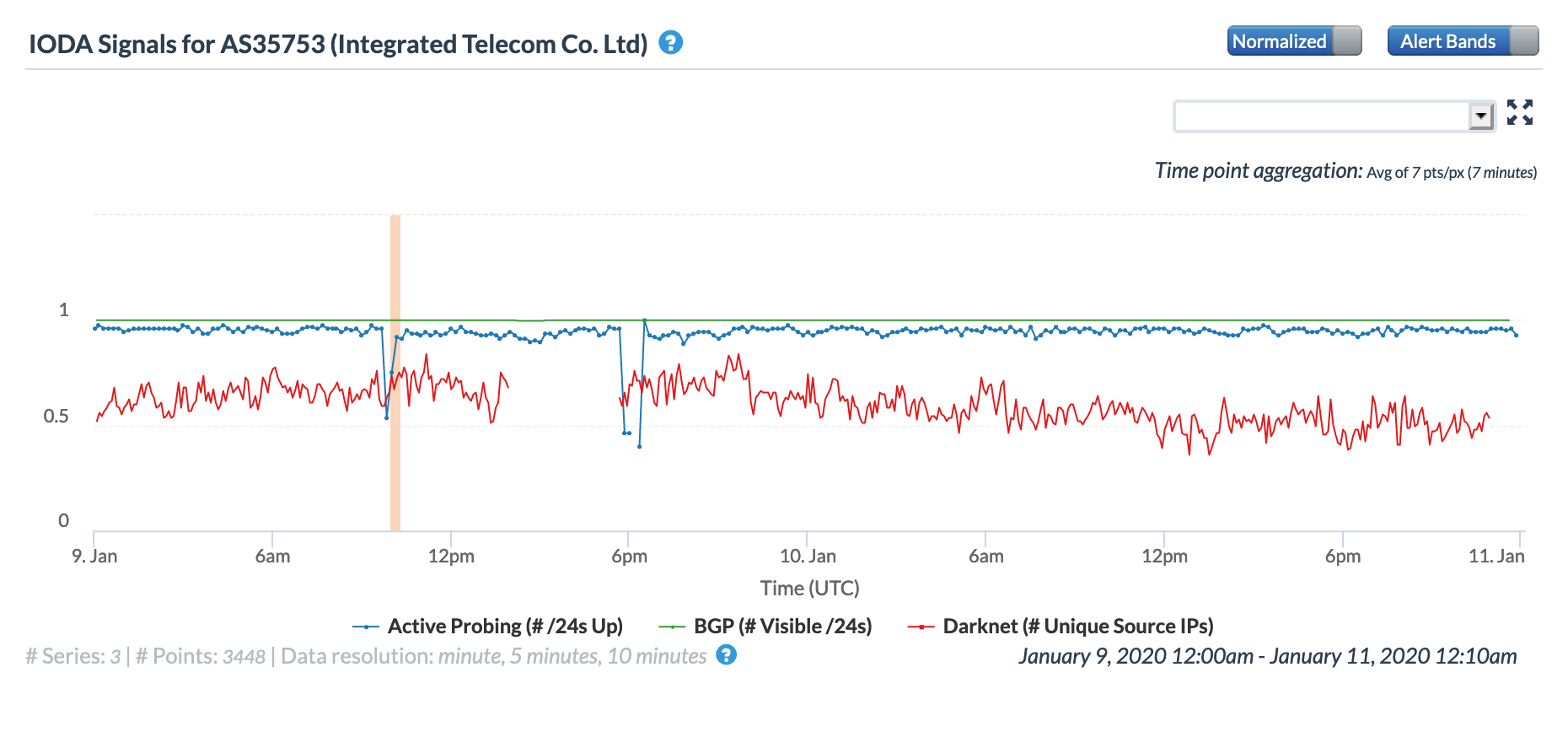

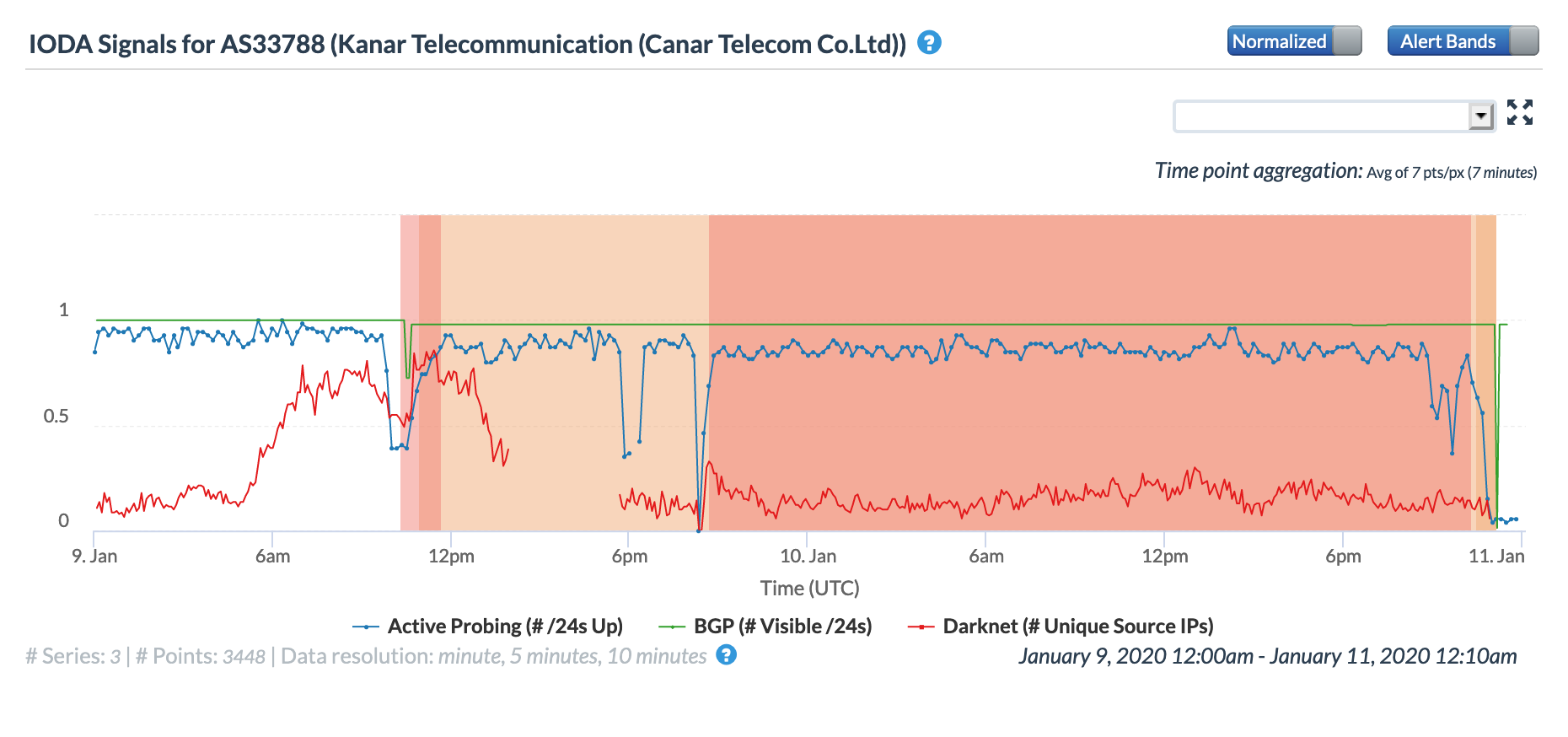

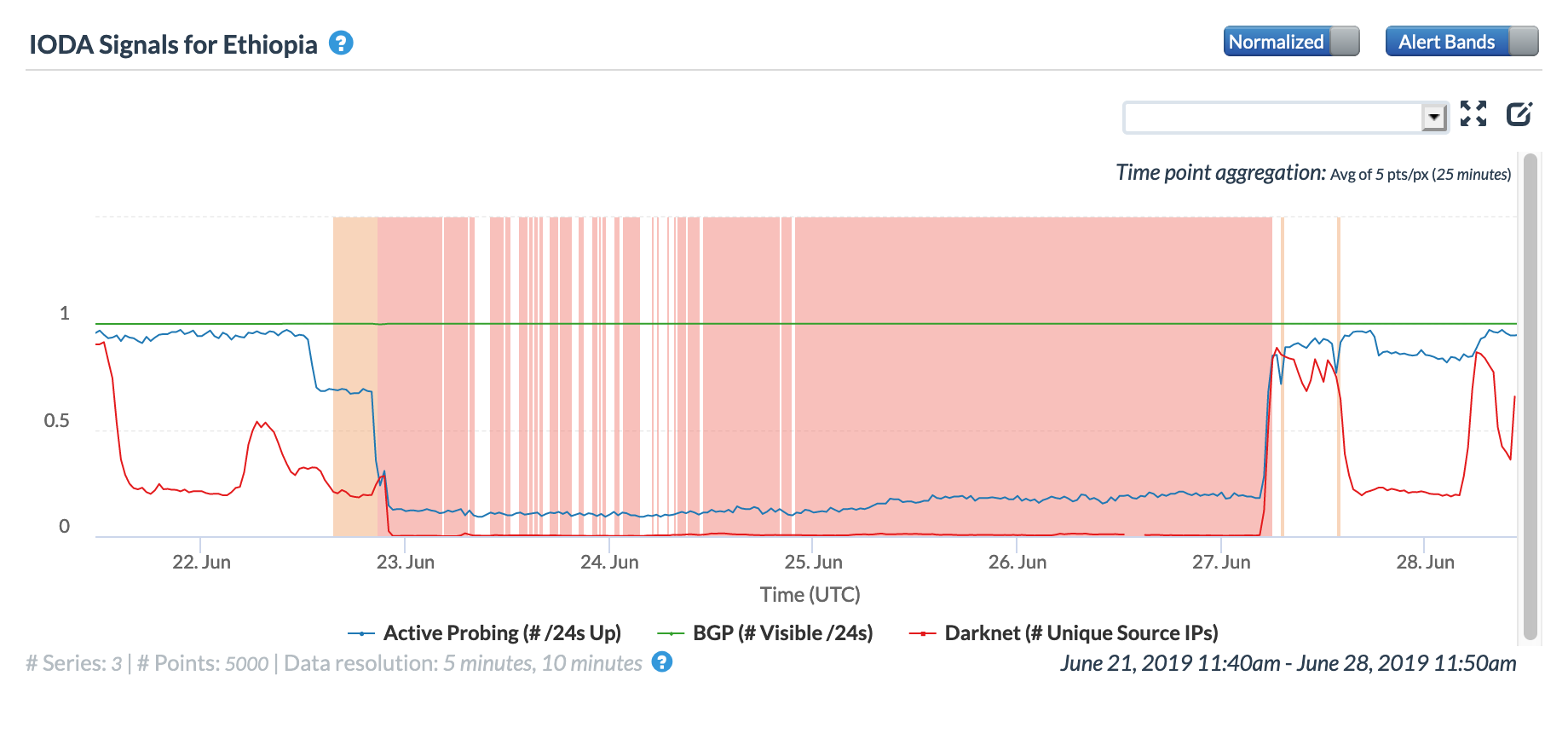

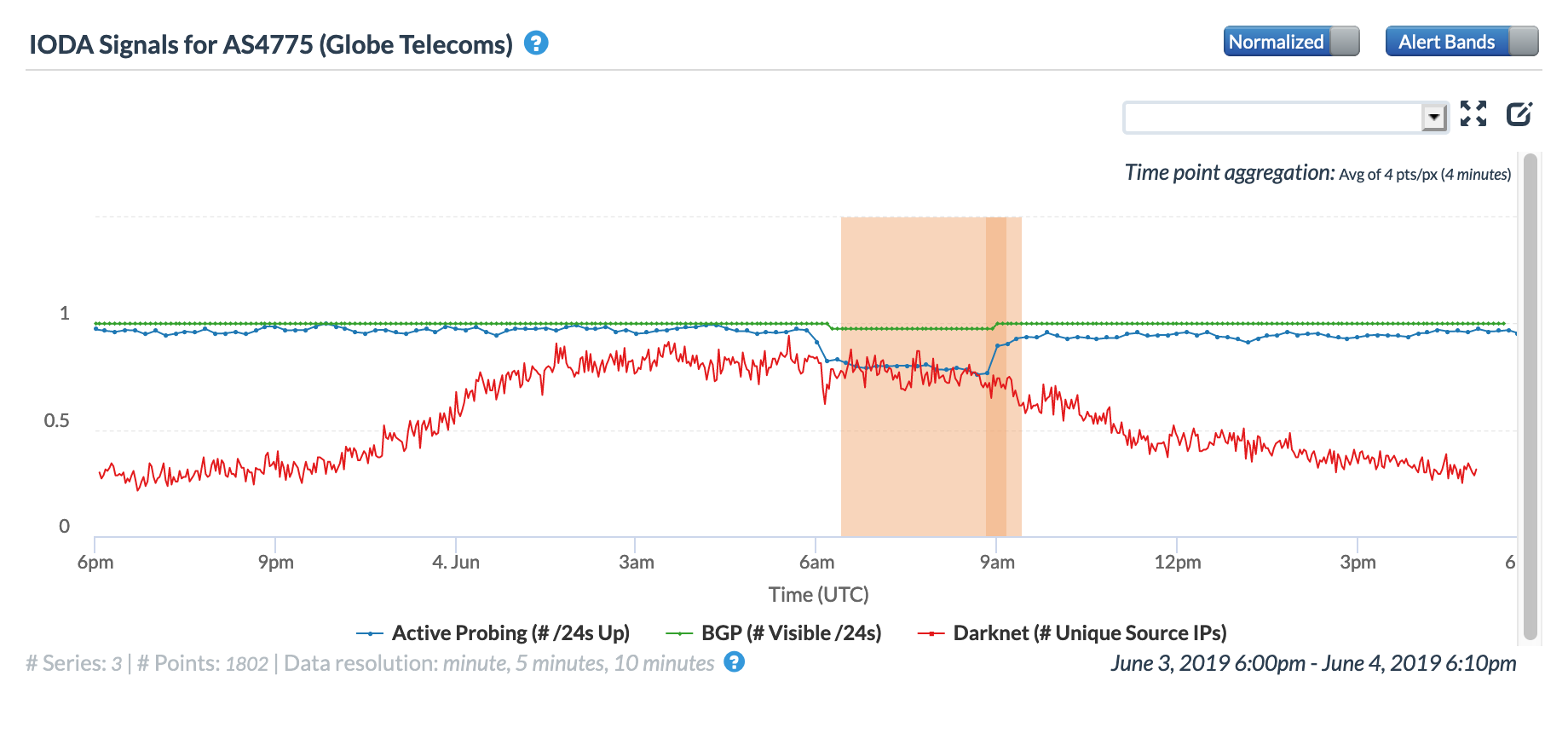

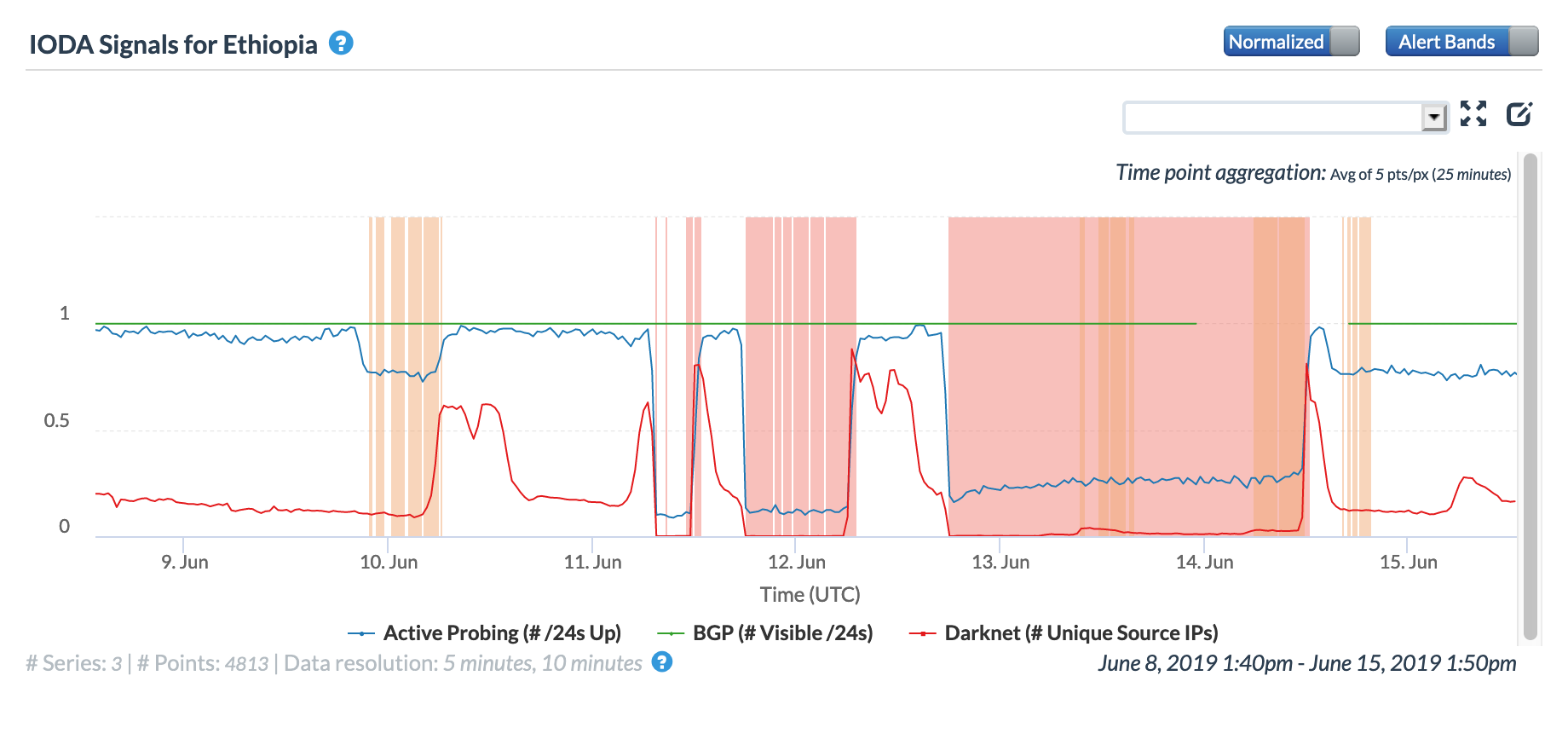

The damage to the FALCON cable also impacted networks in a number of additional countries, including Comoros, Ethiopia, Kuwait, Tanzania, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan. The cable cut is evident in the CAIDA graphs below as a brief drop in the active probing metric. However, the impact is more pronounced in the Oracle Internet Intelligence graphs, where it resulted in increased latency concurrent with traffic shifting to alternate providers.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS36939 (Comores Telecom) , January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS36939 (Comores Telecom), January 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS24757 (Ethio Telecom), January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS24757 (Ethio Telecom), January 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS3225 (Gulfnet Kuwait), January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS3225 (Gulfnet Kuwait), January 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS37182 (Tanzania ERN), January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS37182 (Tanzania ERN), January 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS35753 (Integrated Telecom), January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS35753 (Integrated Telecom), January 9

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS33788 (Canar Telecom), January 9

CAIDA IODA graph for AS33788 (Canar Telecom), January 9

On January 12, Global Cloud Xchange posted an update confirming the damage to the FALCON cable, and noting that the FLAG Europe-Asia (FEA) cable had also been damaged. It stated that “Initial findings indicate that probable cause was an anchor drag by a large merchant vessel in the immediate area.” Just over a month later, Global Cloud Xchange posted another update, announcing the that FALCON submarine cable had been repaired in “record time”, with connectivity restored by February 13. It expected repairs to the FEA cable to be completed by February 22.

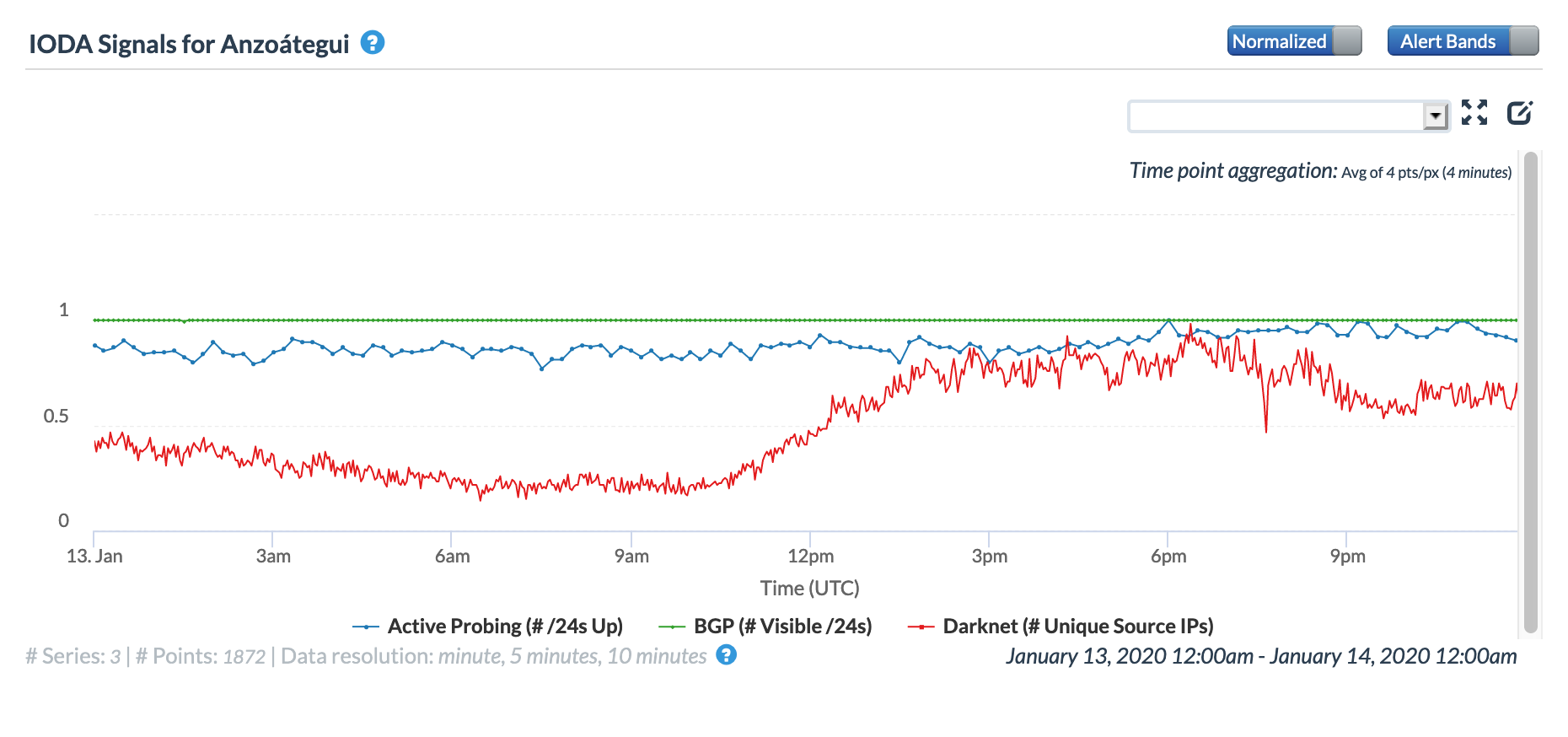

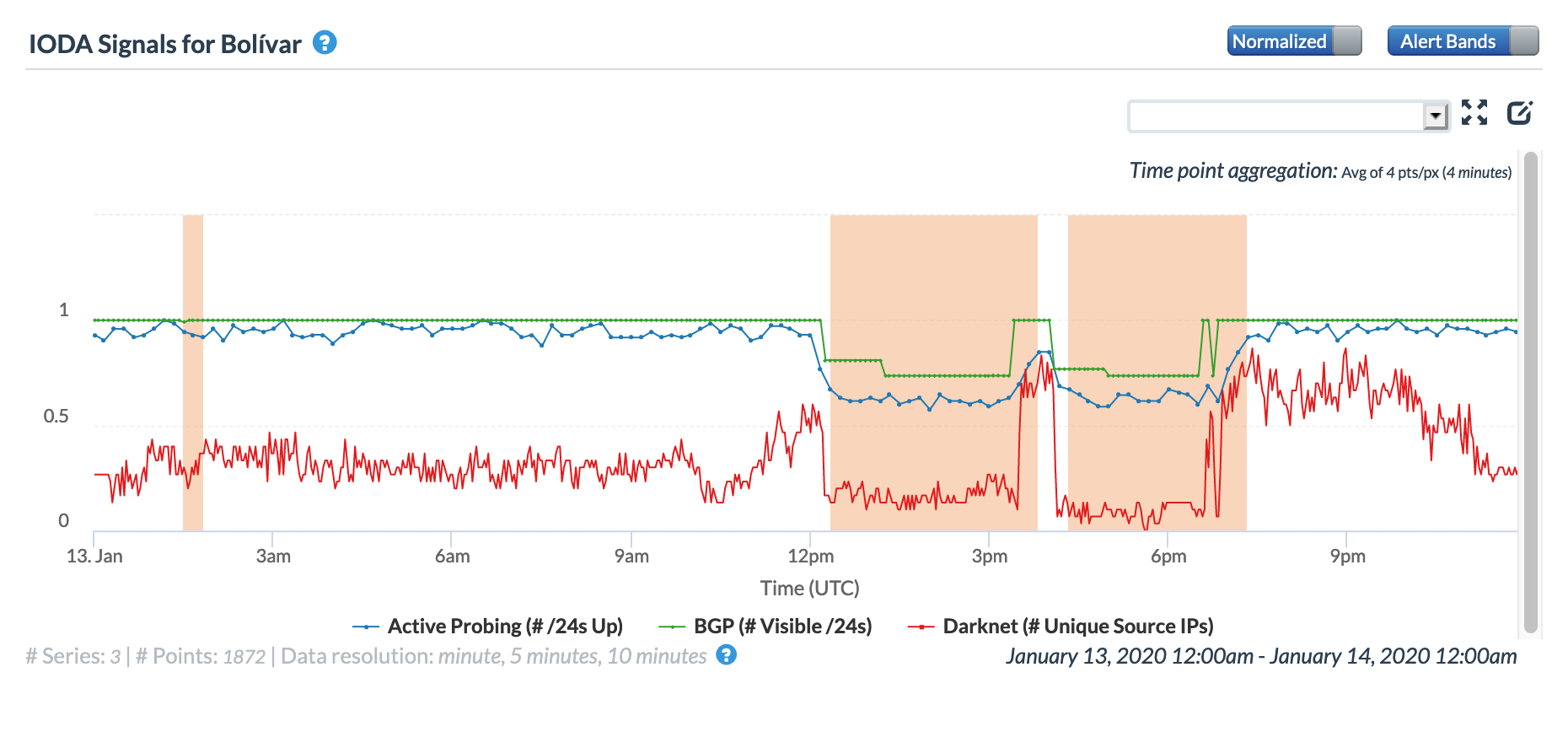

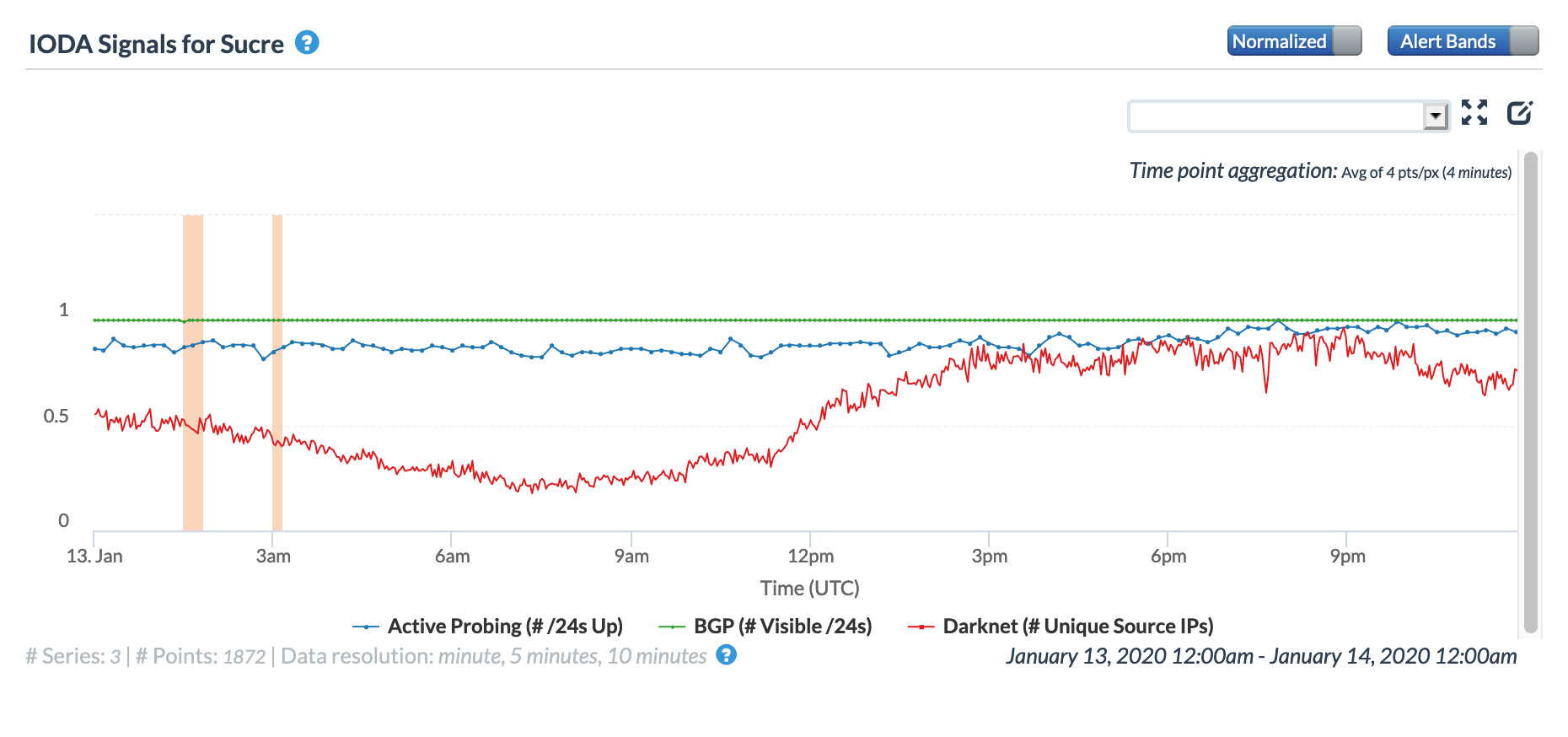

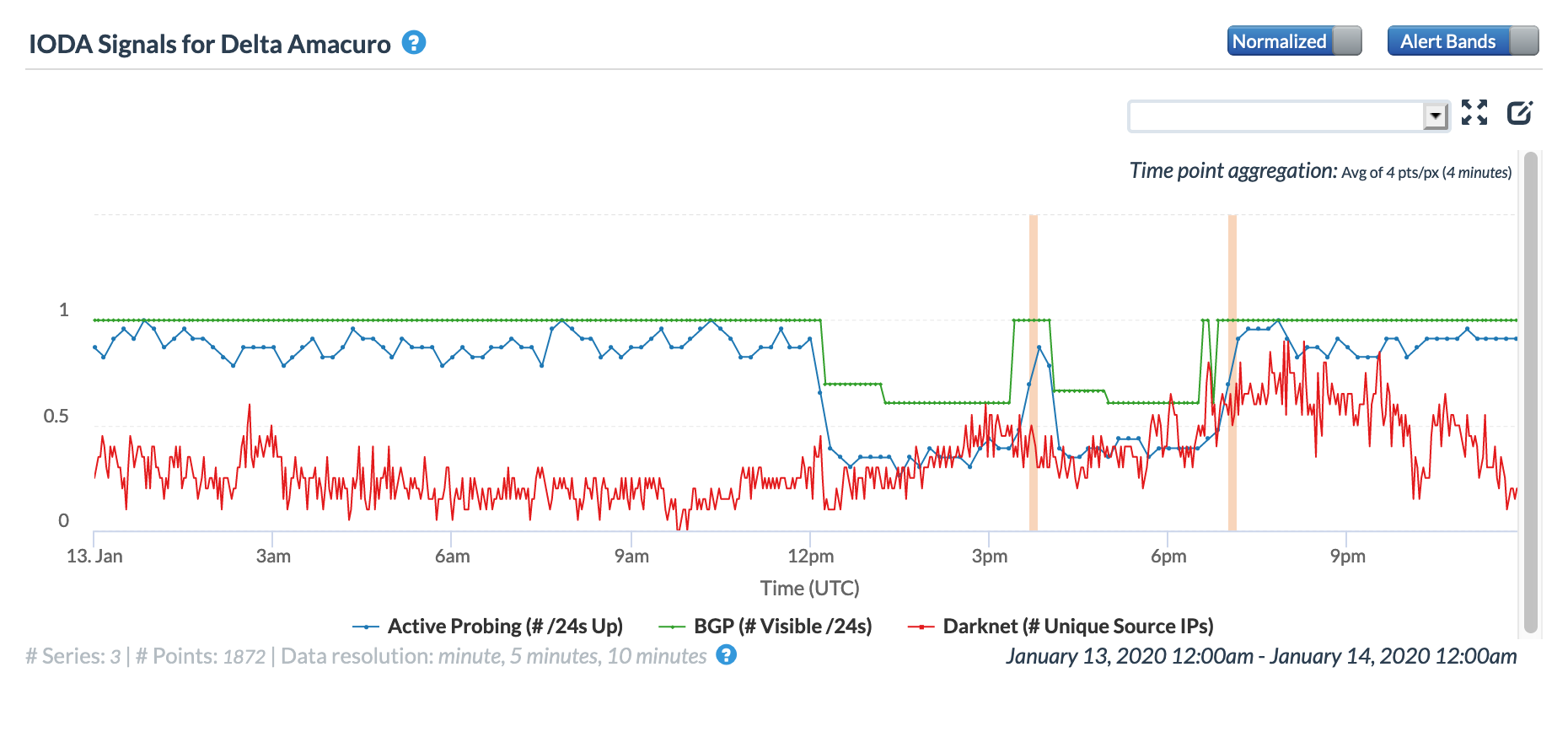

Venezuelan telecommunications provider CANTV Tweeted on January 13 that it was working on restoring telephone and Internet services in the Anzoátegui, Bolívar, Monagas, Sucre and Delta Amacuro states. The CAIDA IODA figures below show the observed impact of the disruption to Internet connectivity for those states, with problems most visible in Bolívar, Monagas, and Delta Amacuro. While the Active Probing metric showed a decline, as would be expected, it is interesting to note that the BGP metric was also impacted, possibly indicating that connectivity to key local routing infrastructure was interrupted.

#13Ene Equipo técnico de #Cantv Región Oriente y Guayana realizaron las maniobras necesarias, para restituir servicios de telefonía fija e Internet en los estados Anzoátegui, Bolívar, Monagas, Sucre y Delta Amacuro. pic.twitter.com/PZ51s0jgiO

— SaladePrensaCantv (@salaprensaCantv) January 13, 2020

CAIDA IODA graph for Anzoátegui, Venezuela, January 13

CAIDA IODA graph for Bolívar, Venezuela, January 13

CAIDA IODA graph for Monagas, Venezuela, January 13

CAIDA IODA graph for Sucre, Venezuela, January 13

CAIDA IODA graph for Delta Amacuro, Venezuela, January 13

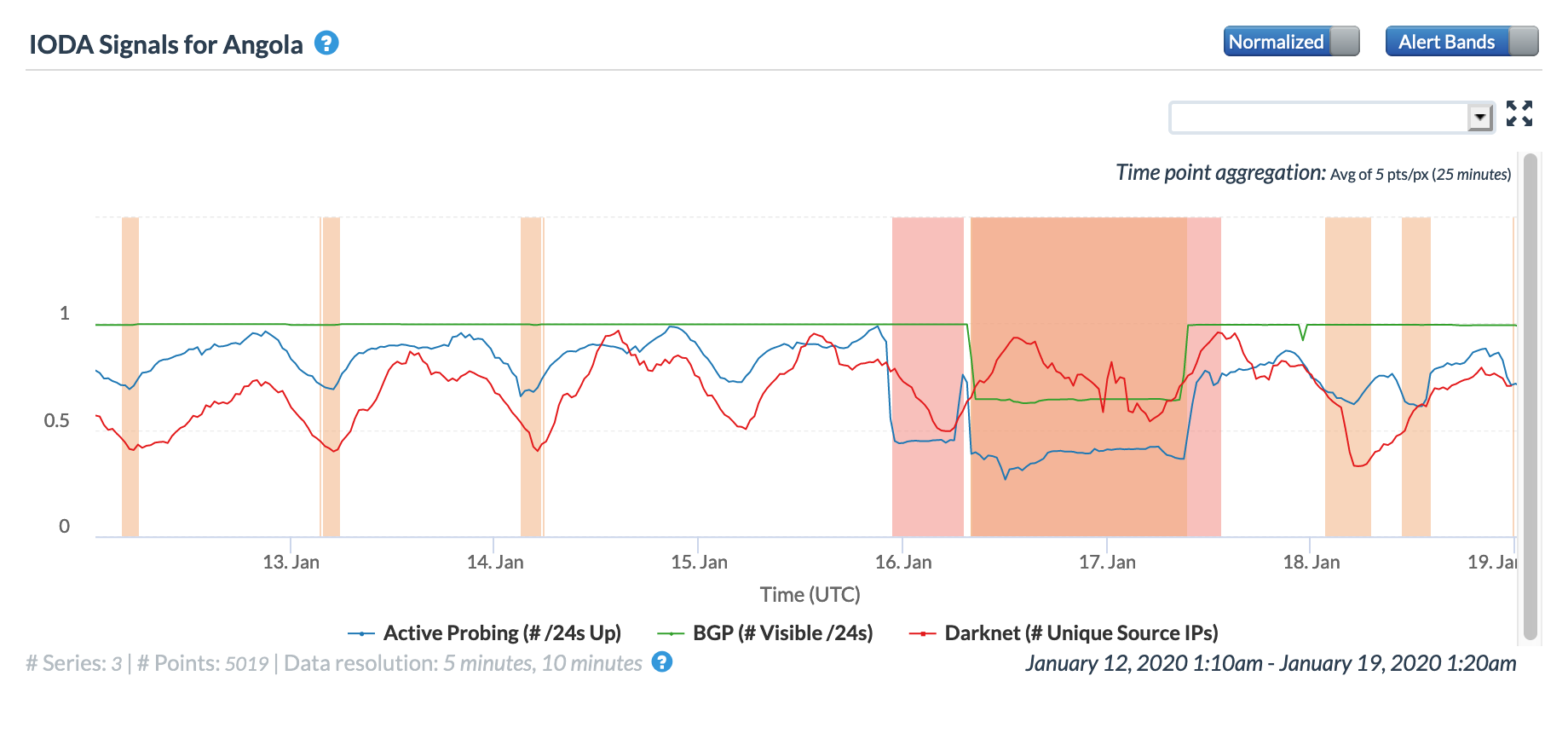

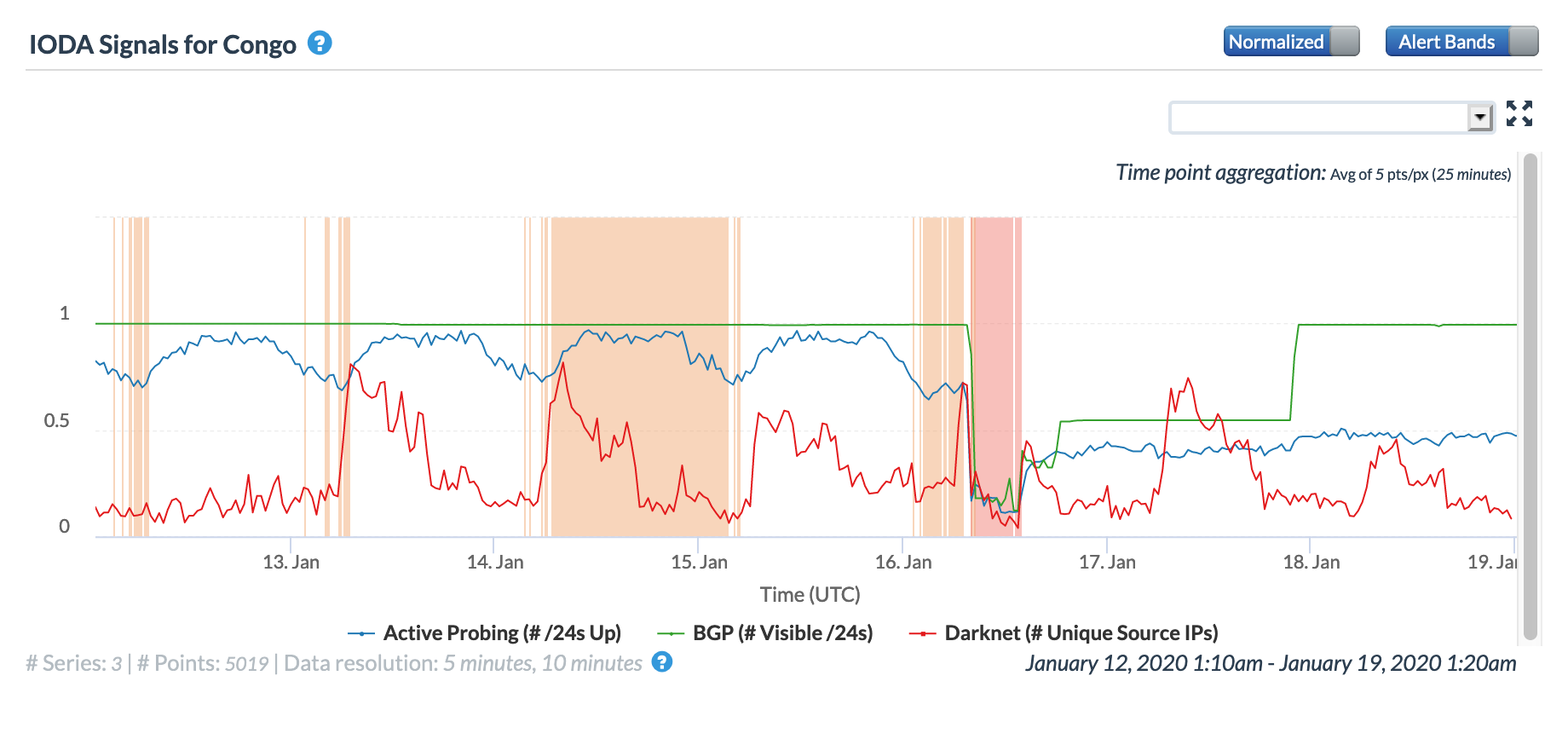

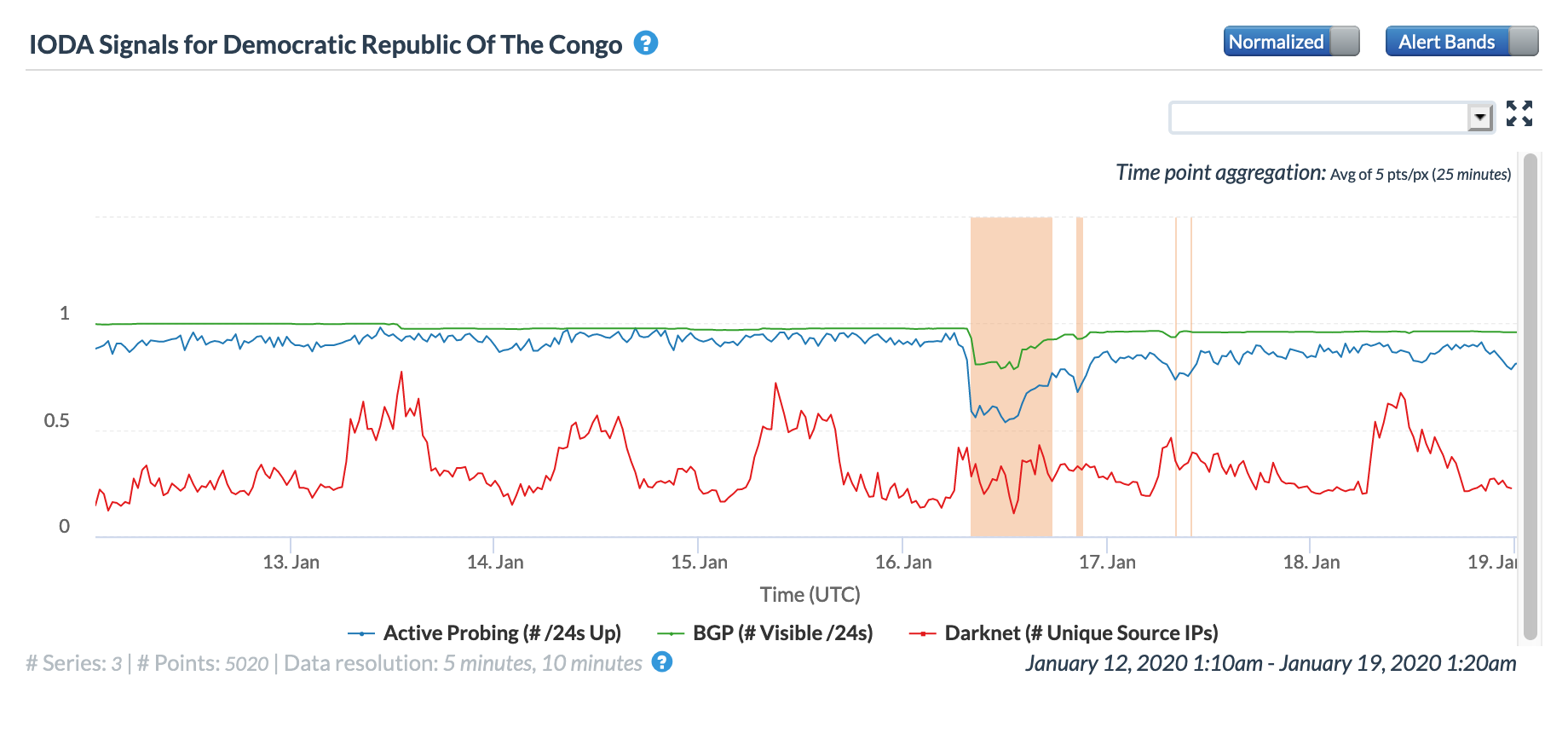

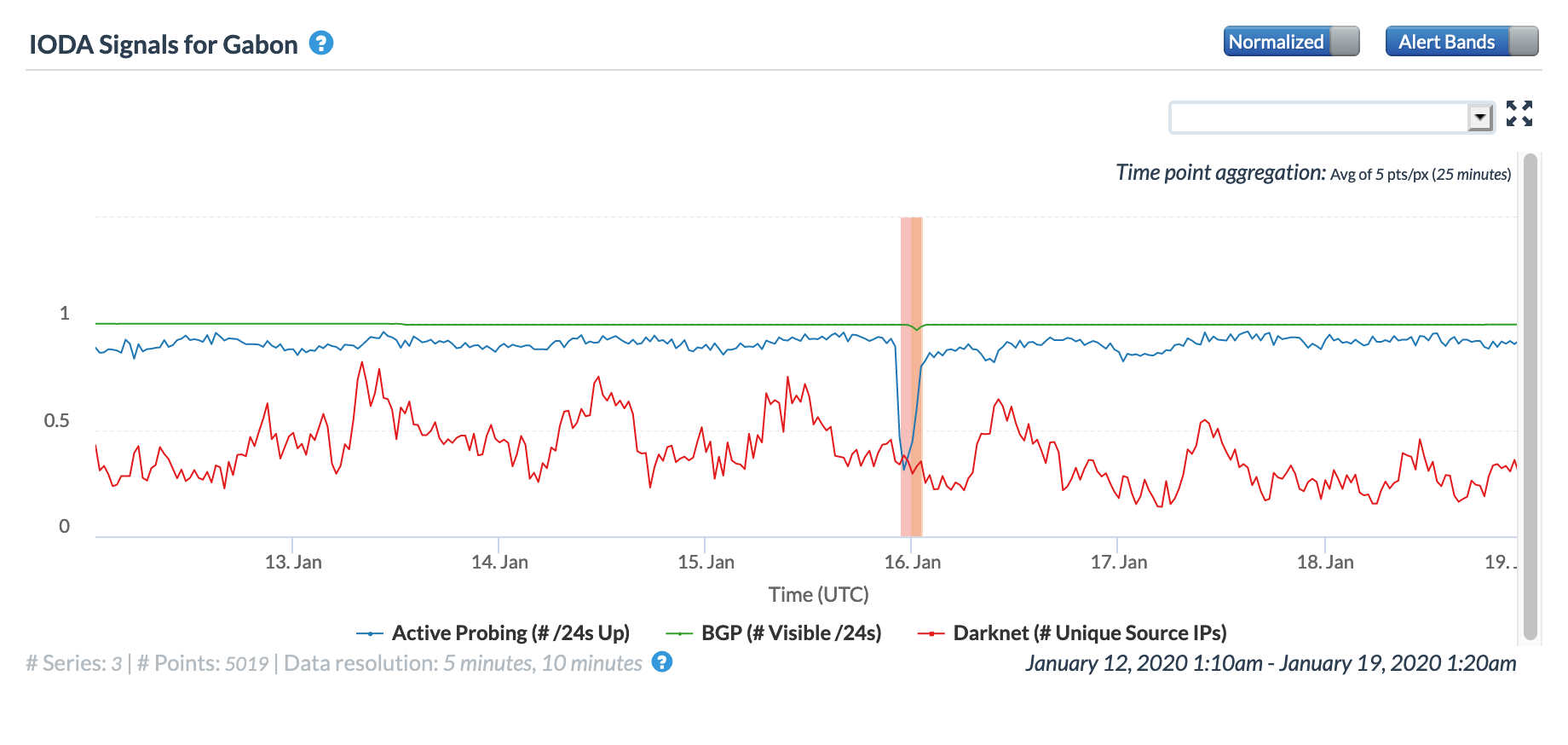

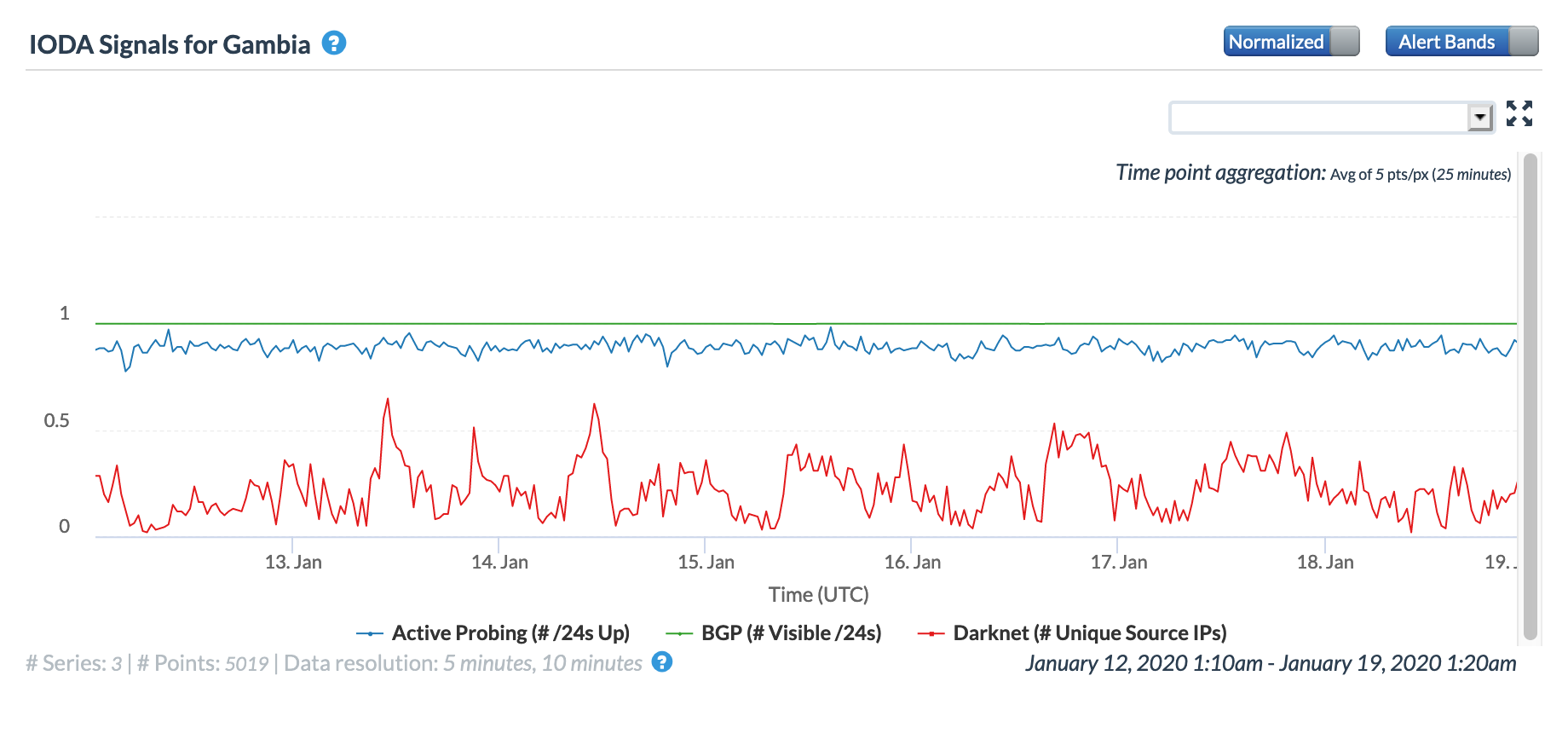

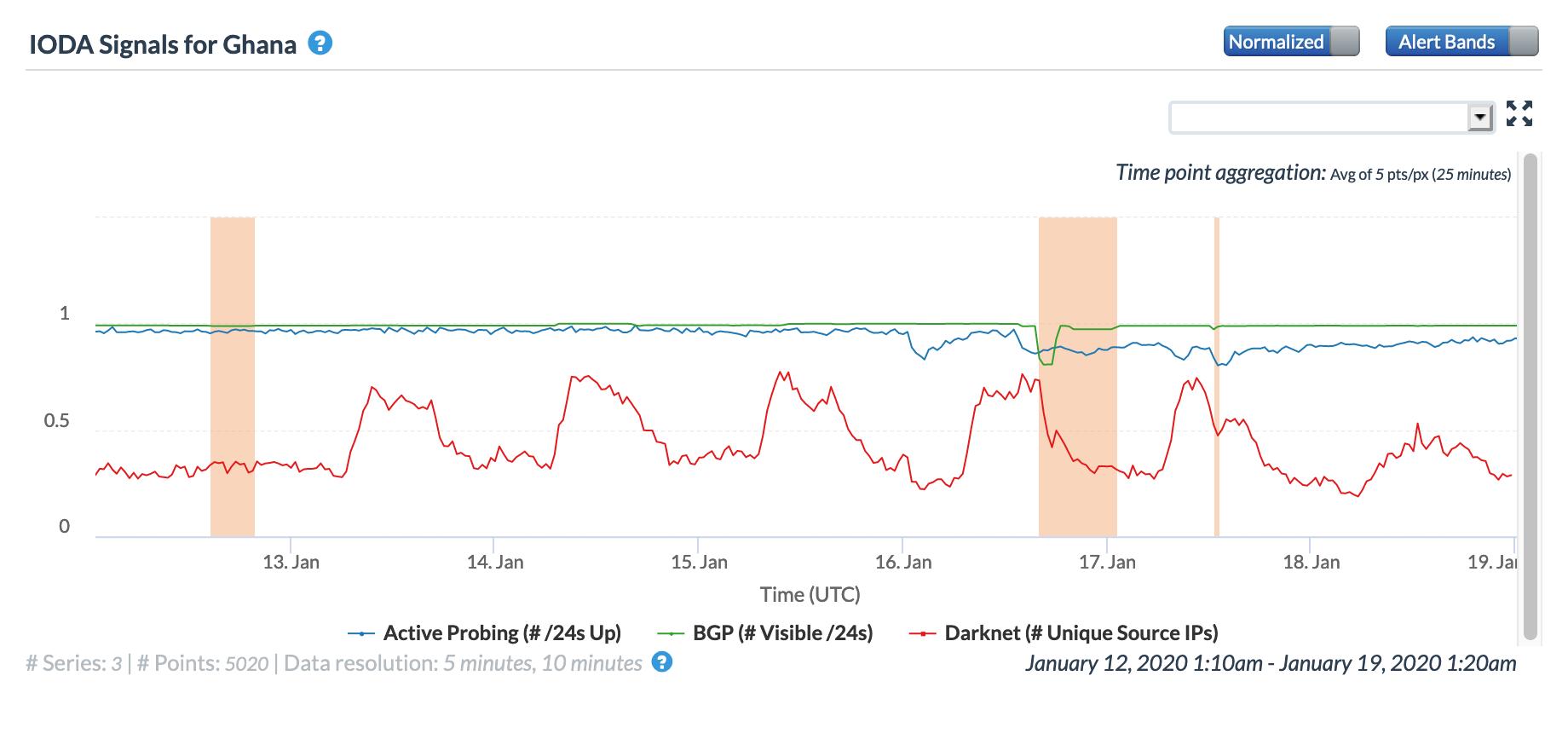

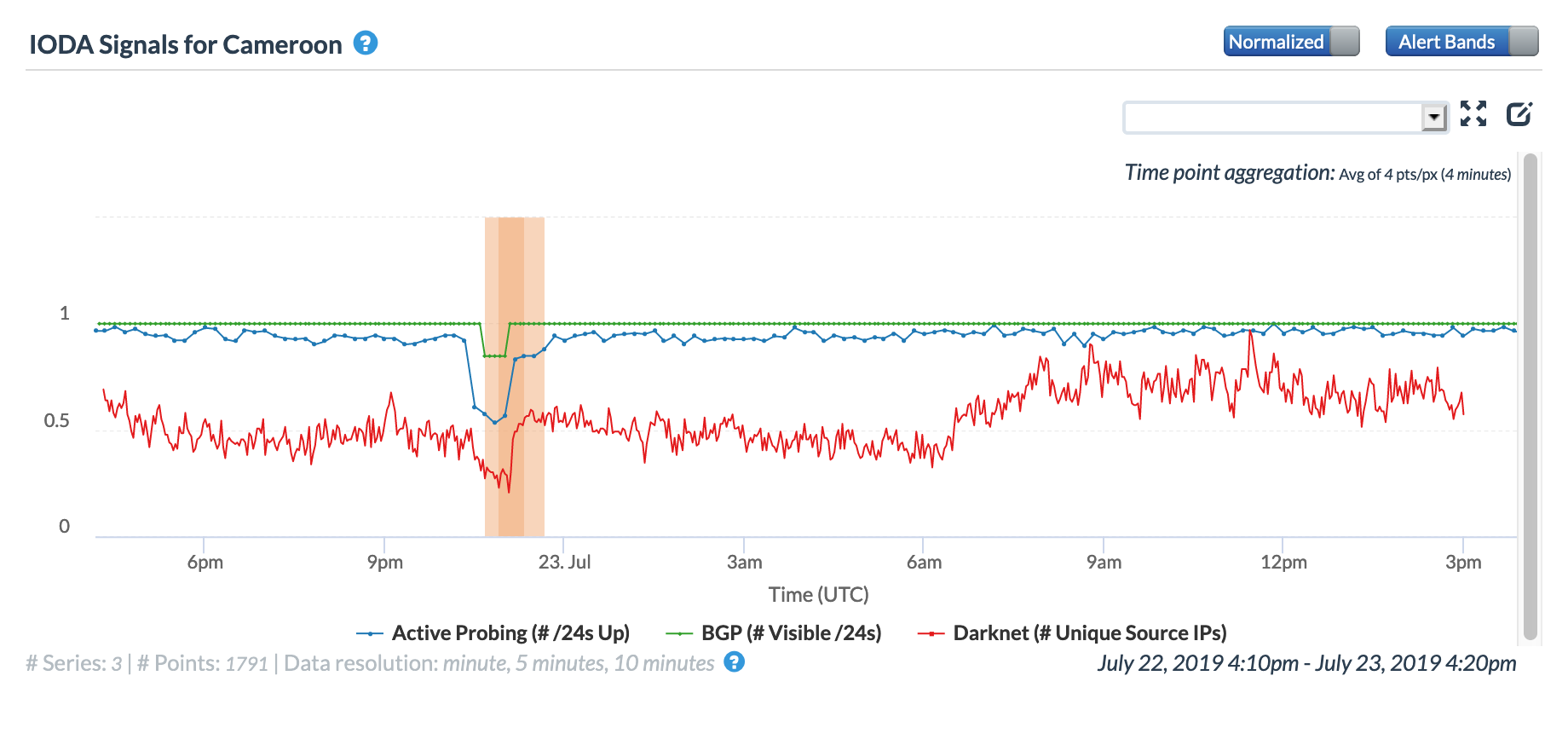

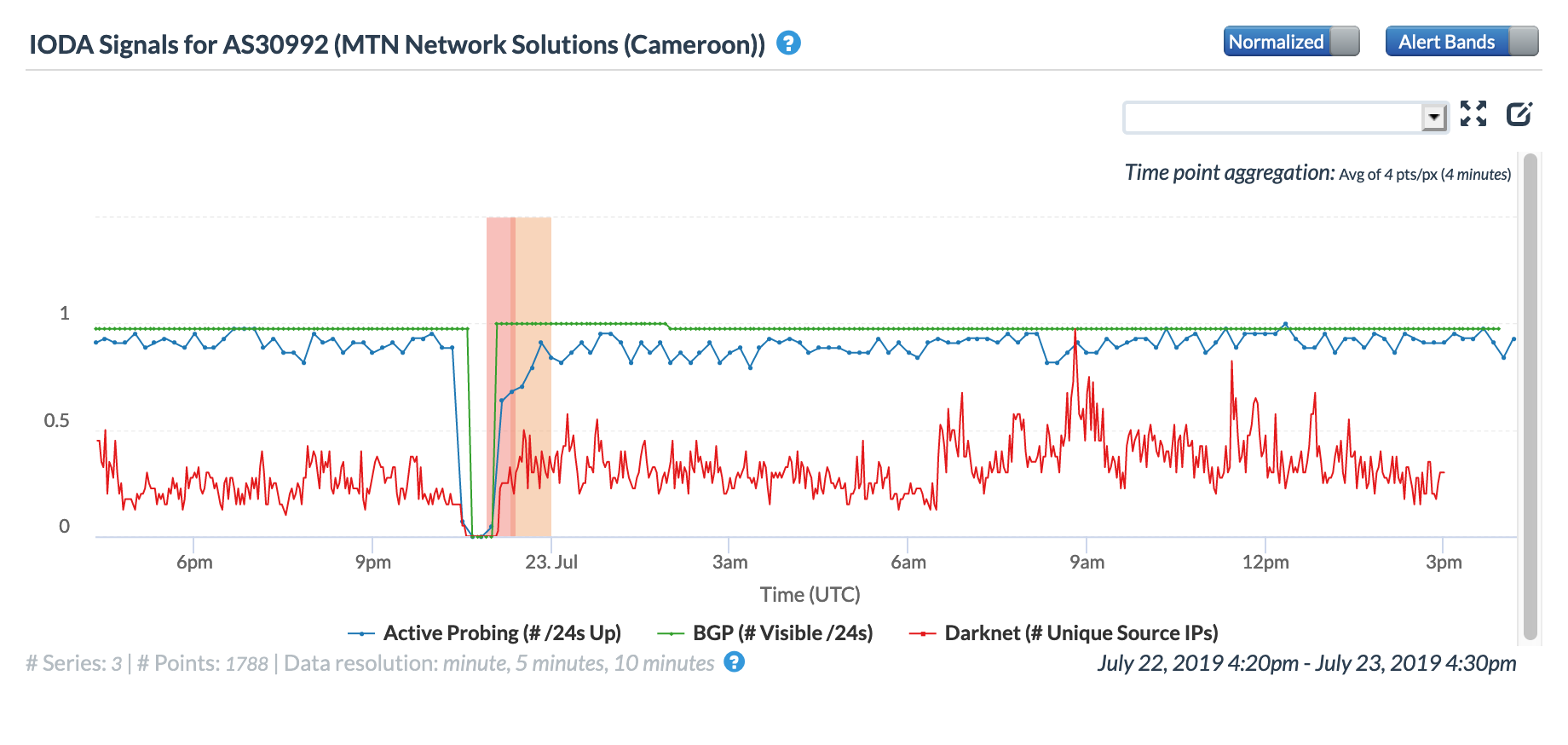

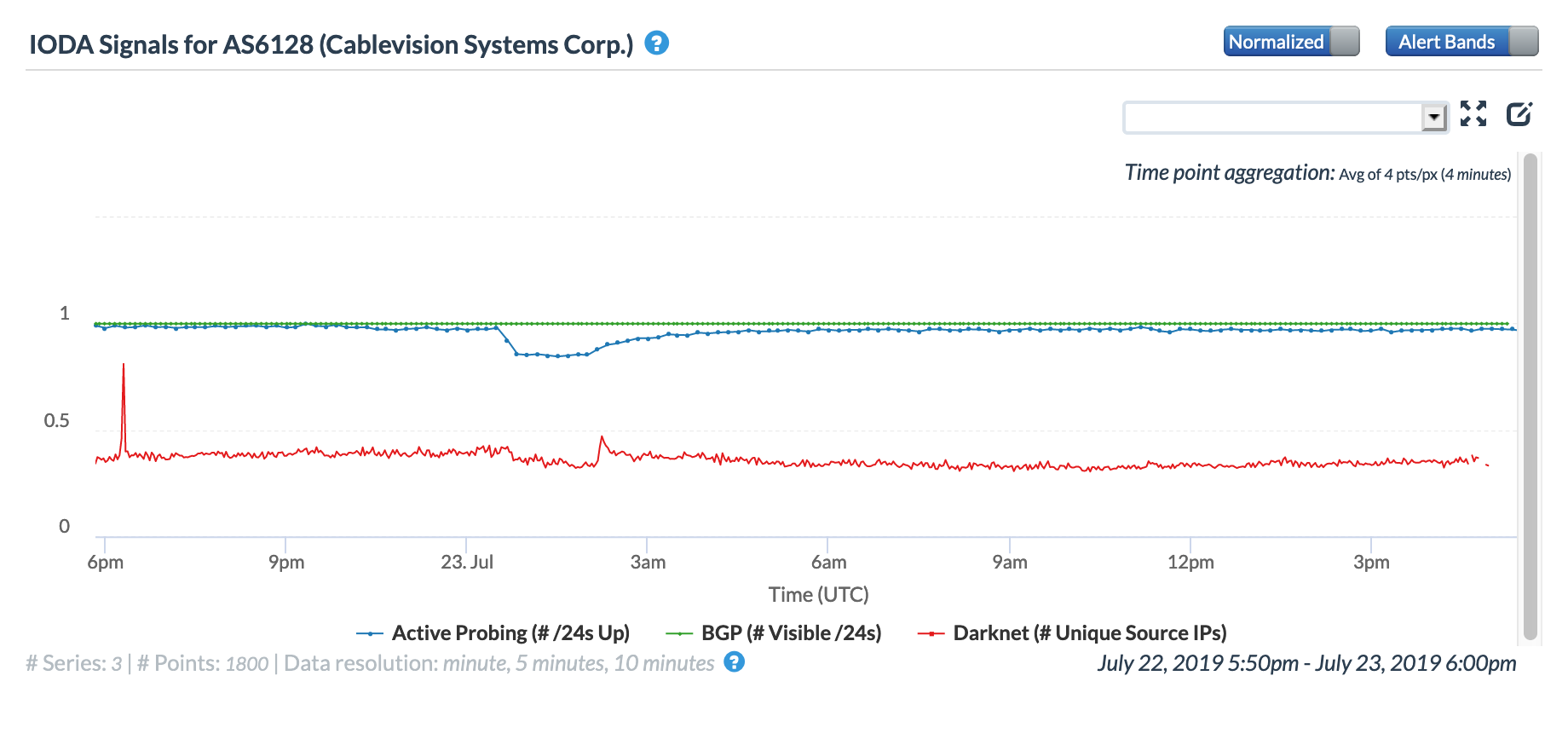

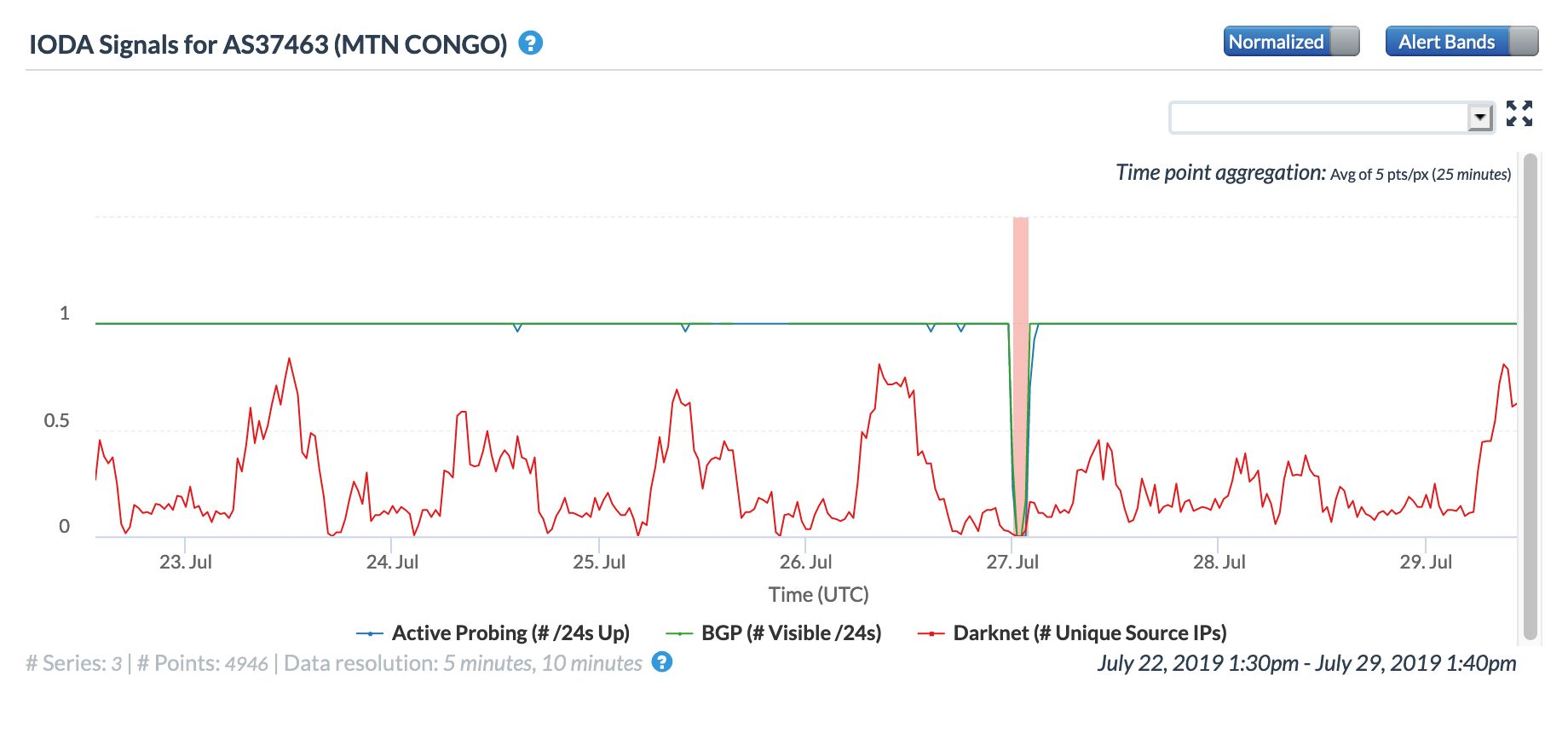

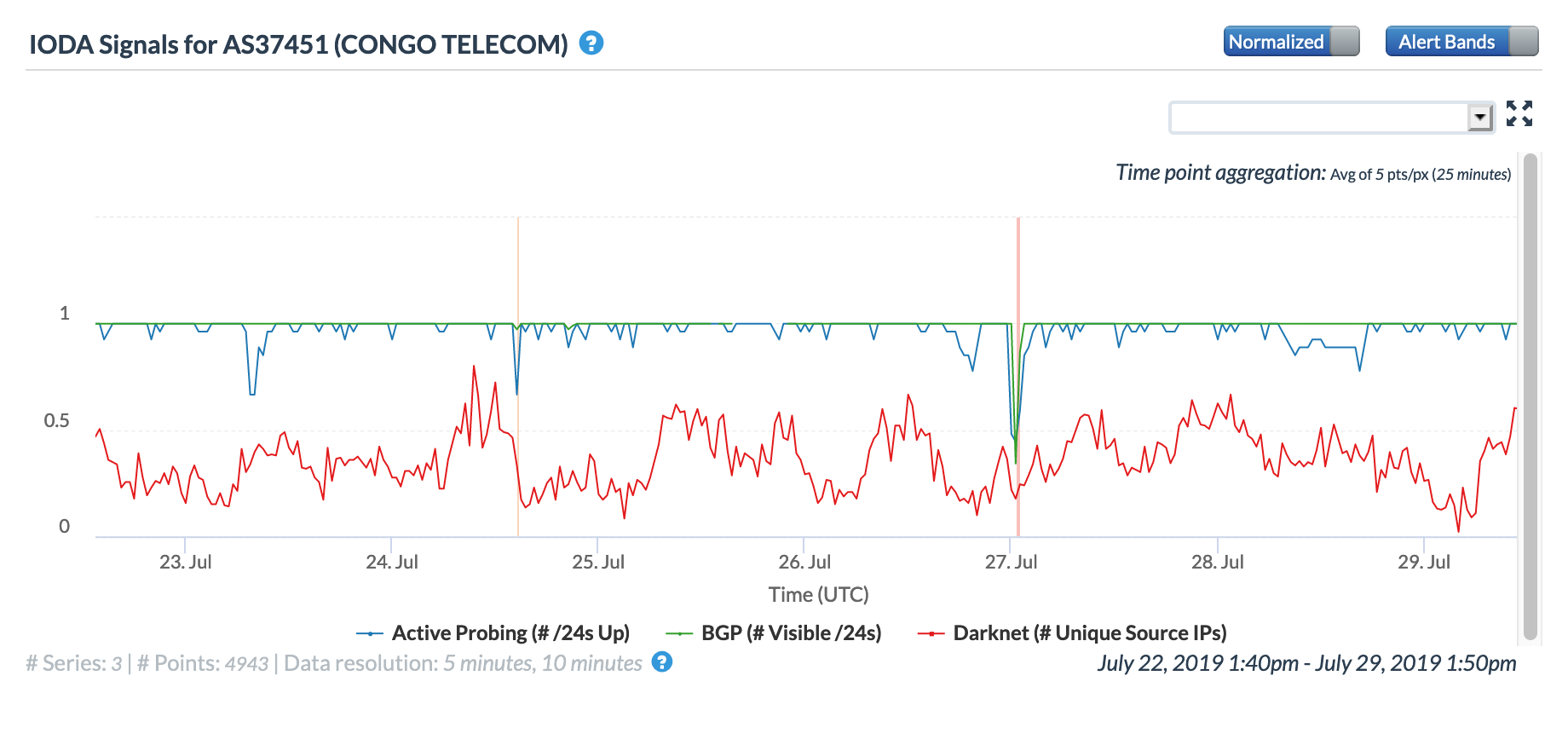

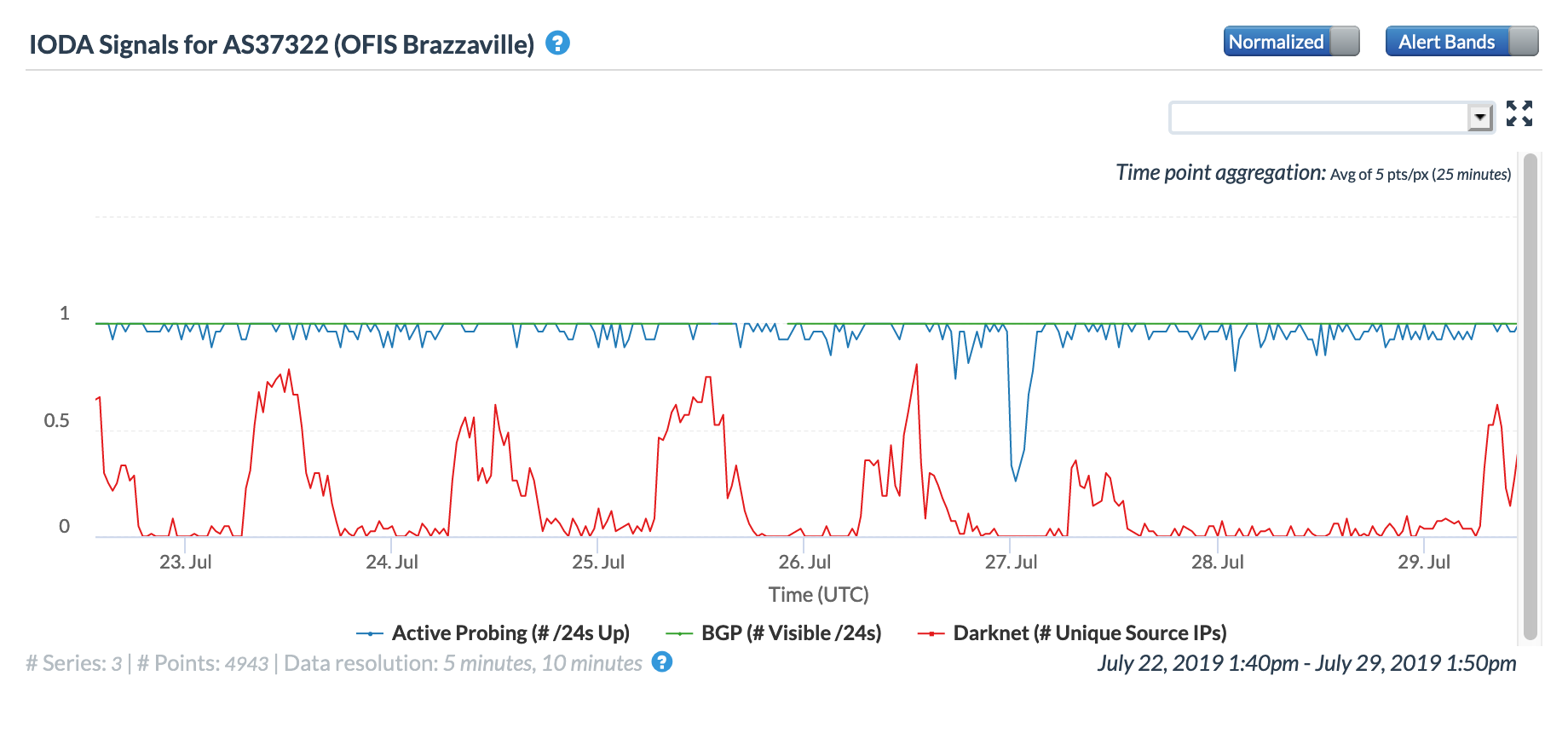

On January 16, Oracle Internet Intelligence Tweeted about a submarine cable outage that happened earlier that morning which severely degraded Internet connectivity for multiple countries along the west coast of Africa. Published reports (including ITWeb, SubTel Forum, and TechCentral) indicated that both the SAT-3/WASC and the West African Cable System (WACS) experienced breaks. The SAT-3/WASC break was reported to be in the vicinity of Libreville, Gabon, while the WACS break was reported to be in the vicinity of Luanda, Angola.

The damage to these submarine cables reportedly disrupted Internet connectivity to a number of African countries, including Angola, Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, the Gambia, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Mali, Mauritania, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The figures below illustrate the impact as measured by Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA, and as seen through Google Web Search traffic from the affected countries.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Angola, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Angola, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Angola, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Cameroon, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Cameroon, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Cameroon, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Congo, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Congo, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Congo, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Democratic Republic of the Congo, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Democratic Republic of the Congo, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Democratic Republic of the Congo, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Gabon, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Gabon, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Gabon, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for the Gambia, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for the Gambia, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for the Gambia, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Ghana, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Ghana, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Ghana, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Ivory Coast, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Ivory Coast, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Ivory Coast, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Mali, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Mali, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Mali, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Mauritania, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Mauritania, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Mauritania, January 16

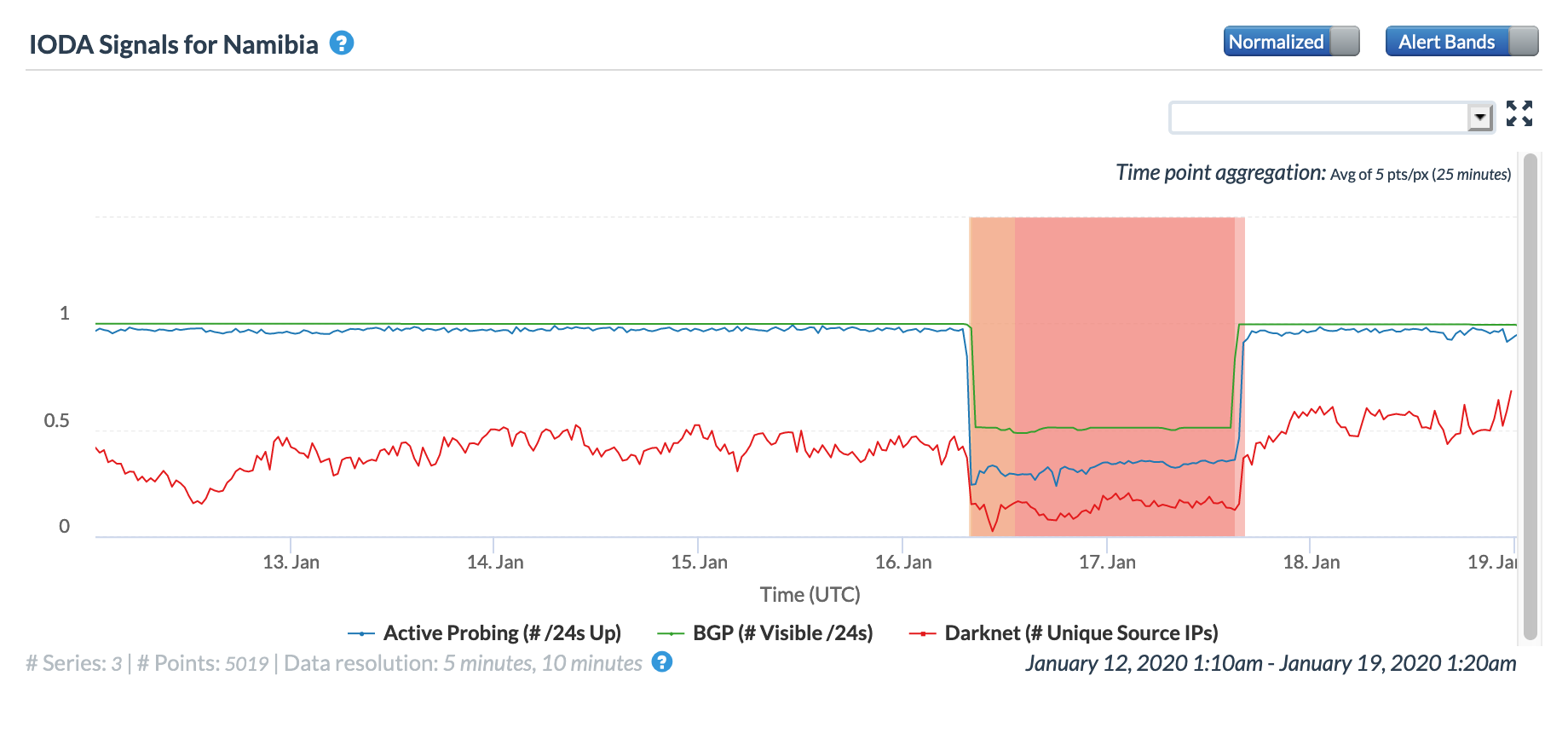

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Namibia, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Namibia, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Namibia, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Niger, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Niger, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Niger, January 16

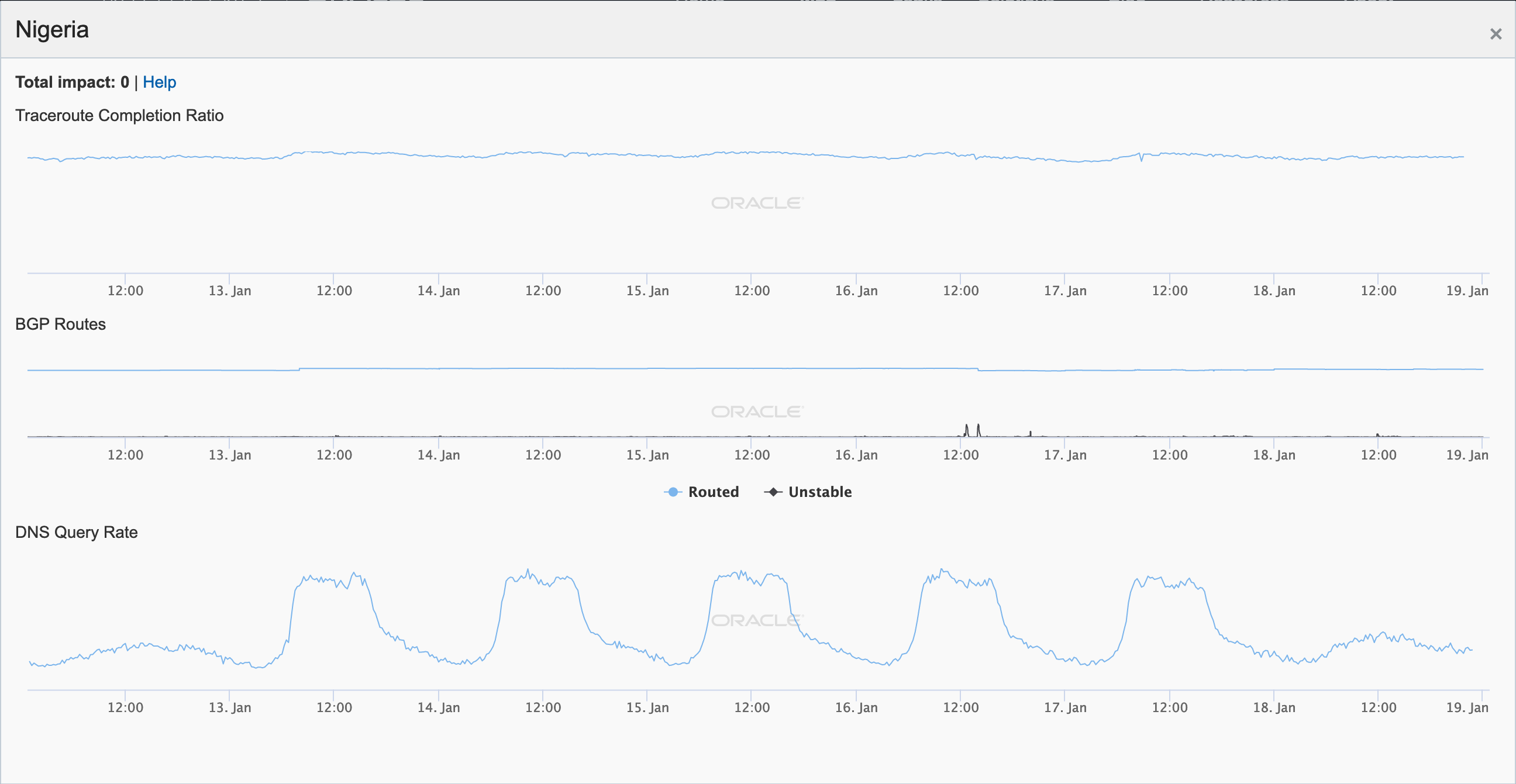

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Nigeria, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Nigeria, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Nigeria, January 16

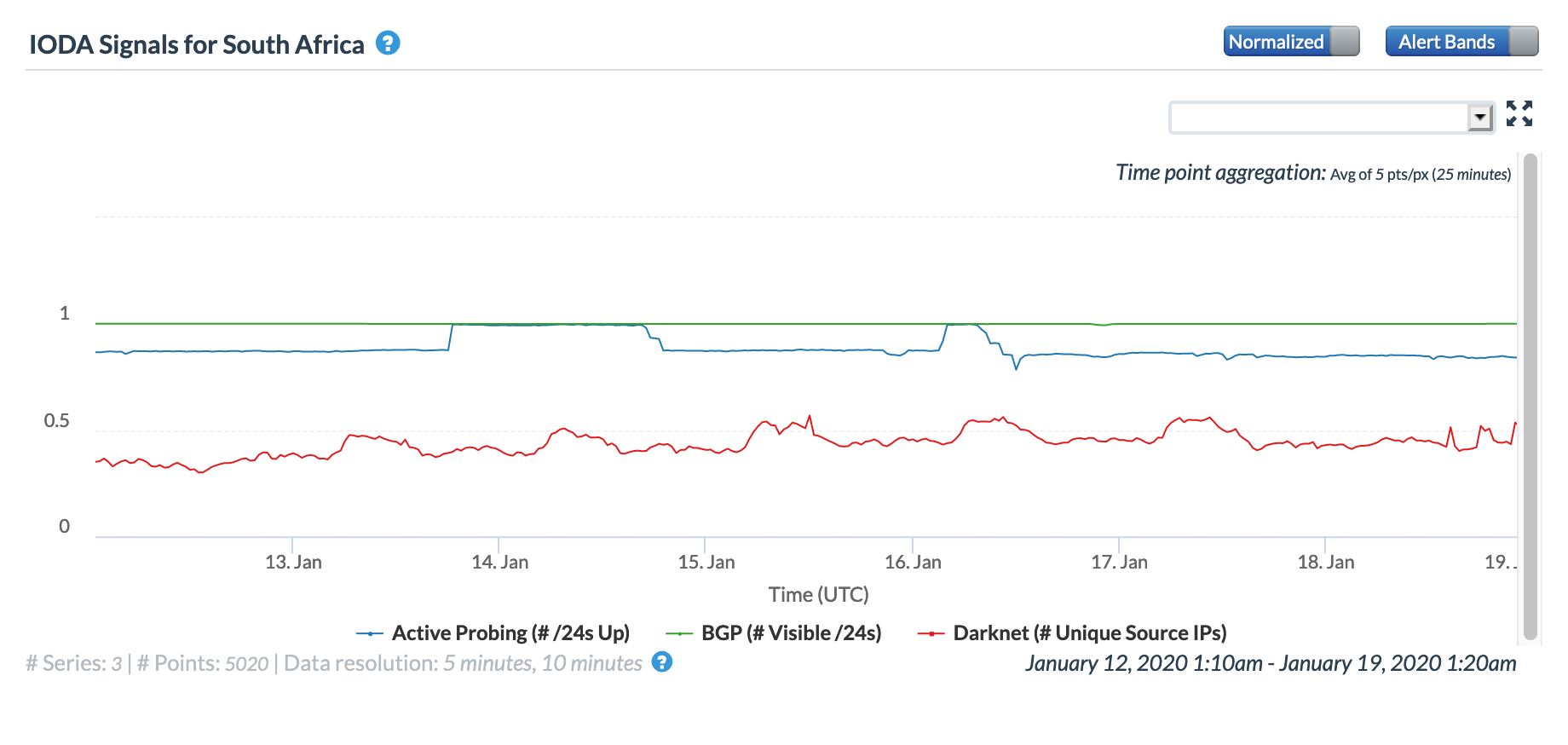

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for South Africa, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for South Africa, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for South Africa, January 16

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Zambia, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Zambia, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Zambia, January 16

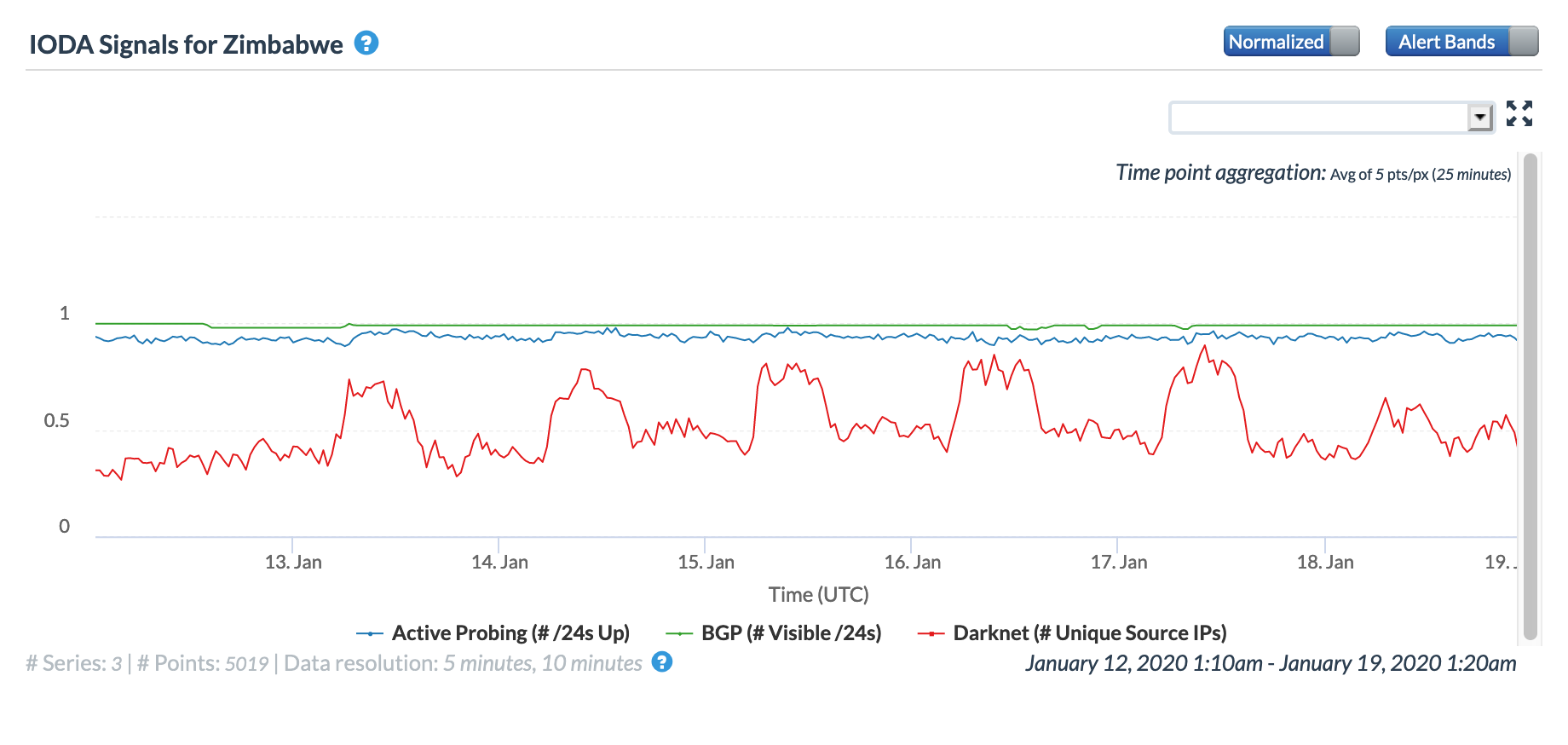

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Zimbabwe, January 16

CAIDA IODA graph for Zimbabwe, January 16

Google Transparency Report traffic graph for Zimbabwe, January 16

In reviewing the figures above, the disruption caused by the cable breaks was most evident in the graphs for Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Namibia, with lesser impact evident in Angola, Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, and Ivory Coast.

As expected, the Internet disruption was heavily covered on news Web sites in the impacted countries, and affected telecom providers including Telecom Namibia, MTN Namibia, CAMTEL, Cool Ideas, and RSAWeb provided status updates to subscribers via social media or their corporate Web sites.

The WACS cable was reportedly damaged by “heavy sediment”, and connectivity was fully restored on both the WACS and SAT-3/WASC cable systems by February 19, according to a published report.

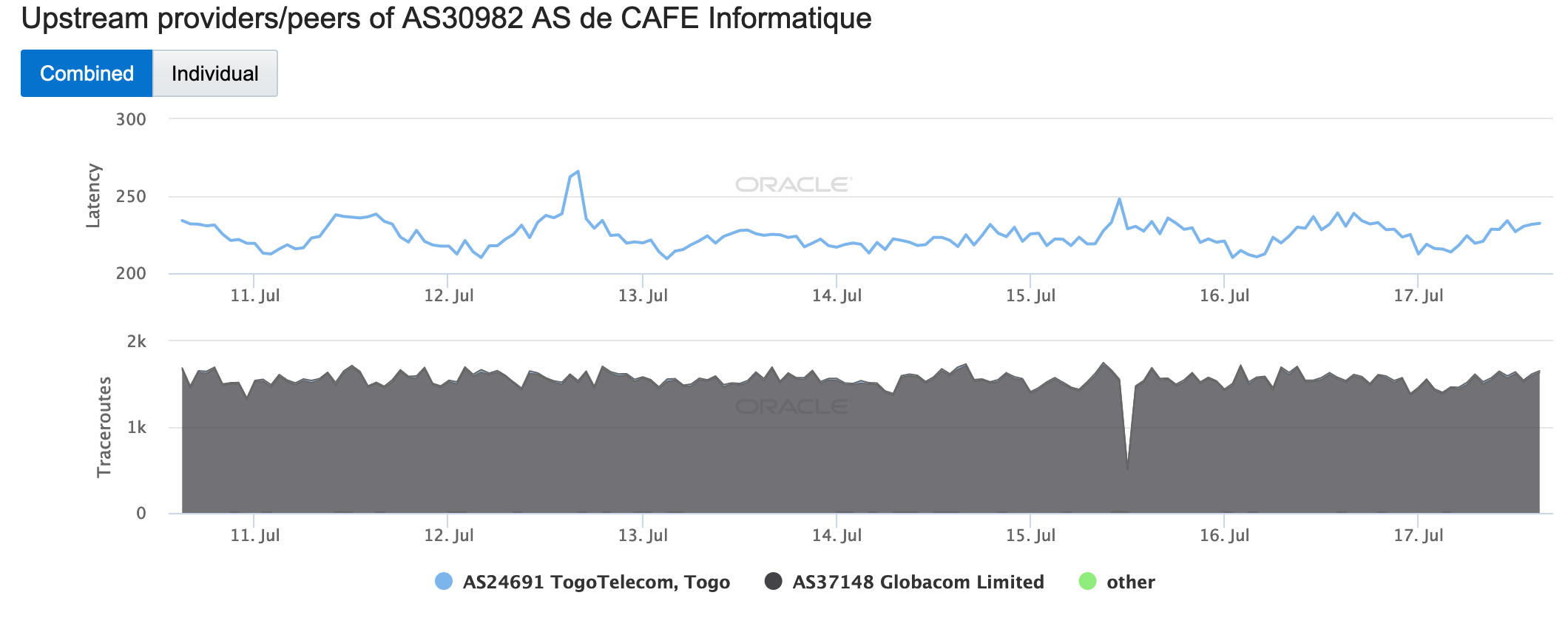

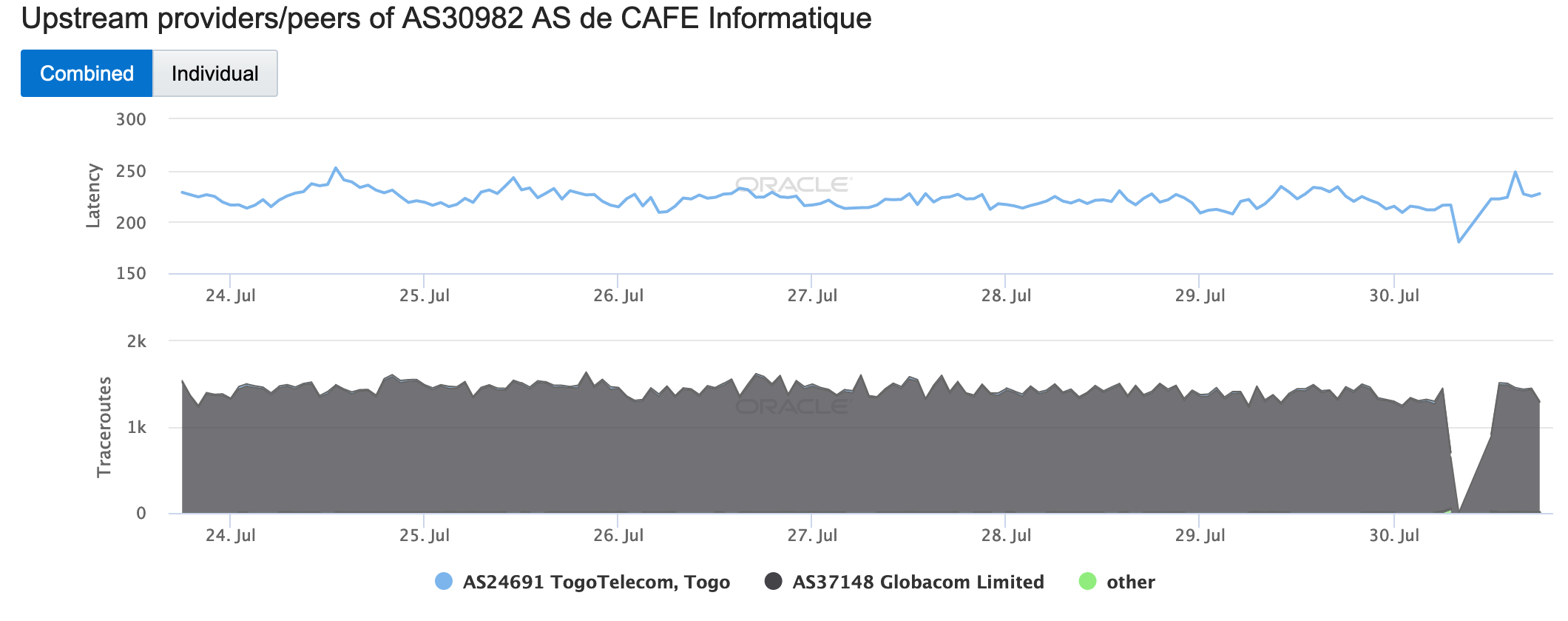

On January 23, Togo Telecom posted the Tweet below alerting customers that an Internet disruption that started the day before was due to a problem with the WACS cable.

Togocom vous présente ses excuses pour ce désagrément indépendant de sa volonté et vous remercie pour votre patience et votre confiance. pic.twitter.com/sfwOzNN7j8

— TOGO TELECOM (@TOGOTELECOM1) January 23, 2020

Dear clients,

Since Wednesday January 22, 2020. Togo, like all the sub-region, whose internet connection depends on the West African submarine cable (WACS- West African Cable System) faces a partial or total absence of internet service This follows to a double section on the submarine cable segments as well as on the terrestrial backup segment.

The Togocom teams as well as the international teams of the cable operator are already hard at work for the rapid resolution of this incident. All the means are implemented by all the stakeholders for an effective and rapid resolution of the problem. ,

Togocom will keep you informed in real time of the progress of the work to restore complete internet service.

Togocom apologizes for this inconvenience beyond its control and thanks you for your patience and your confidence.

(via Google Translate)

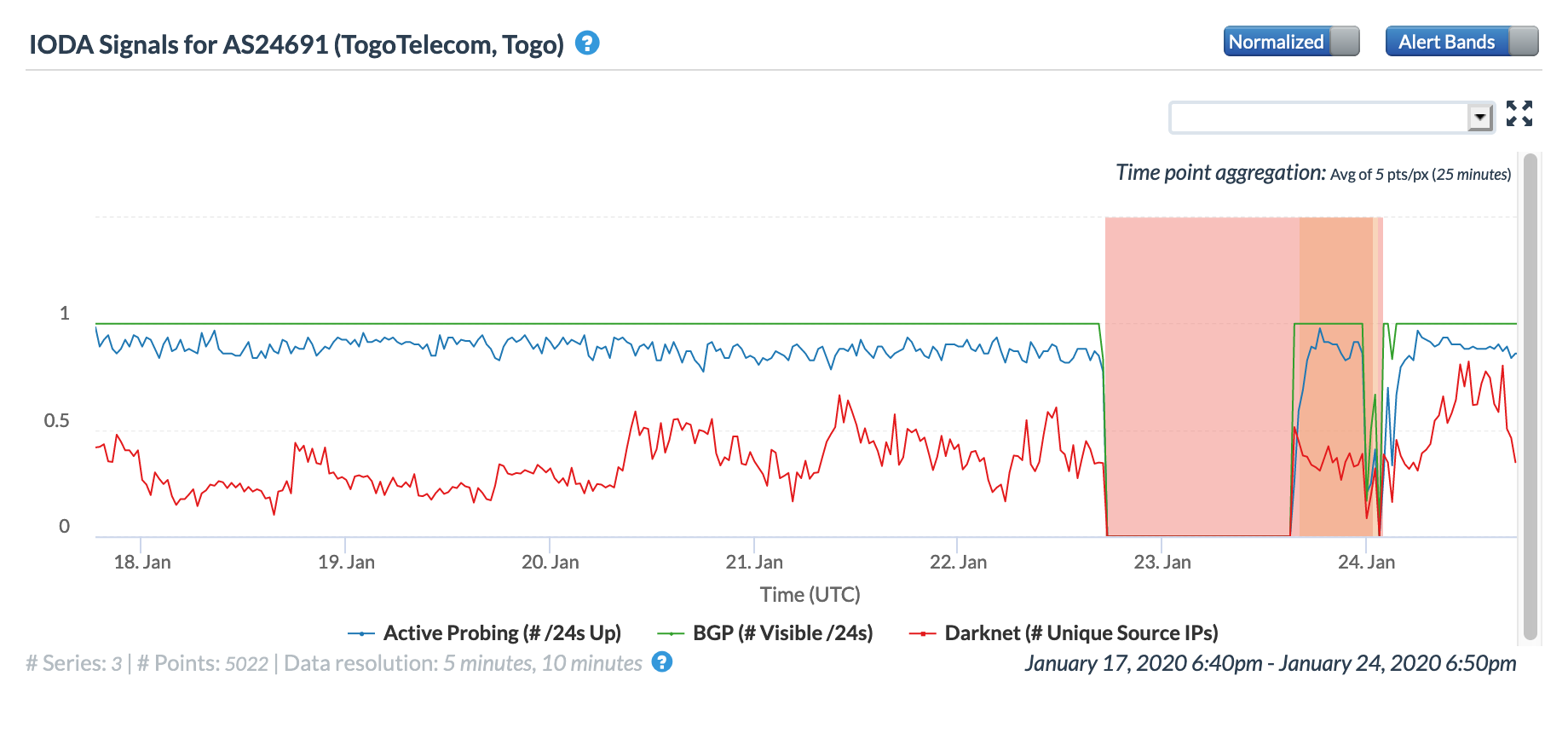

The figures below illustrate the impact of this problem on Internet connectivity at a country level in Togo, as well as to connectivity to Togo Telecom.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Togo, January 22-23

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS24691 (Togo Telecom), January 22-23

CAIDA IODA graph for AS24691 (Togo Telecom), January 22-23

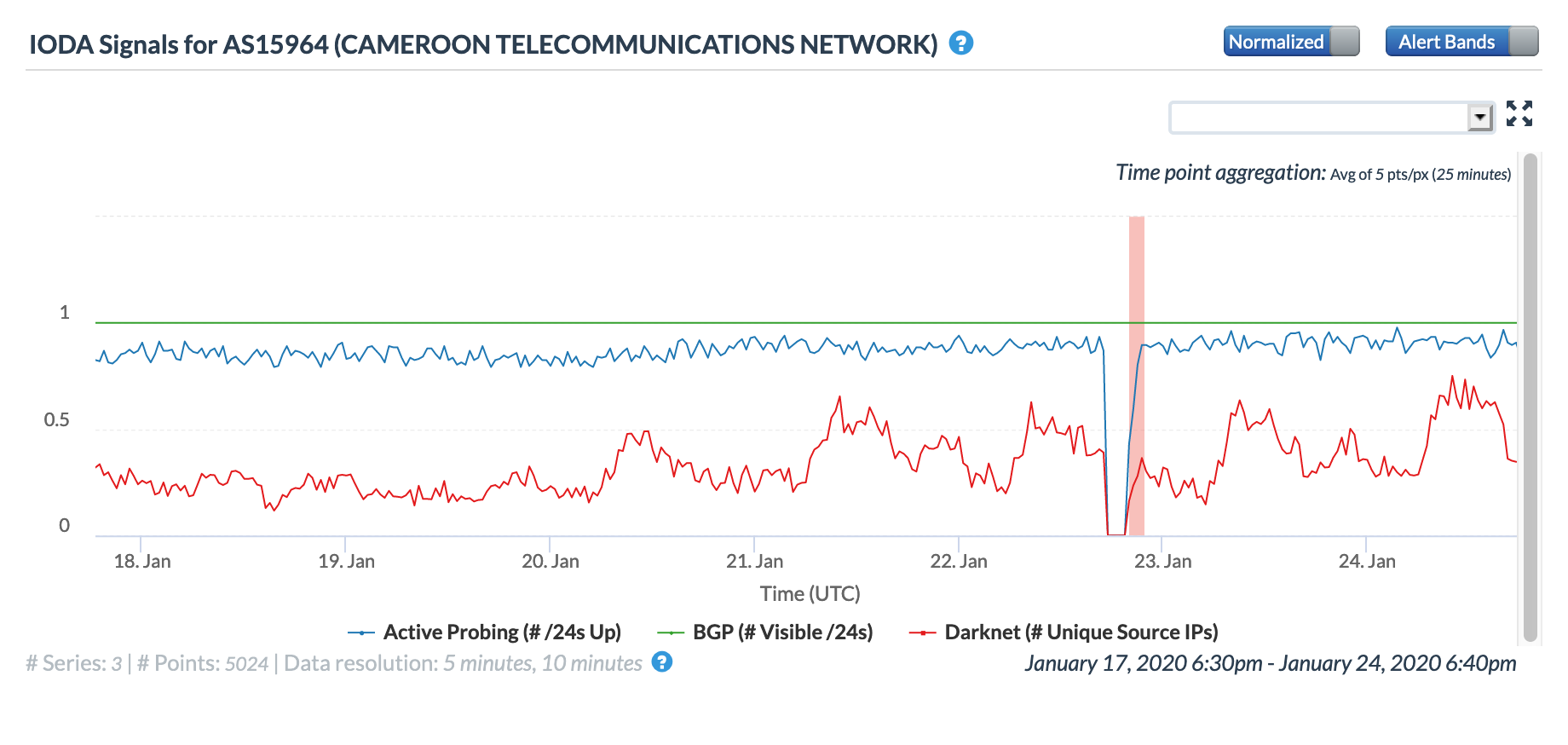

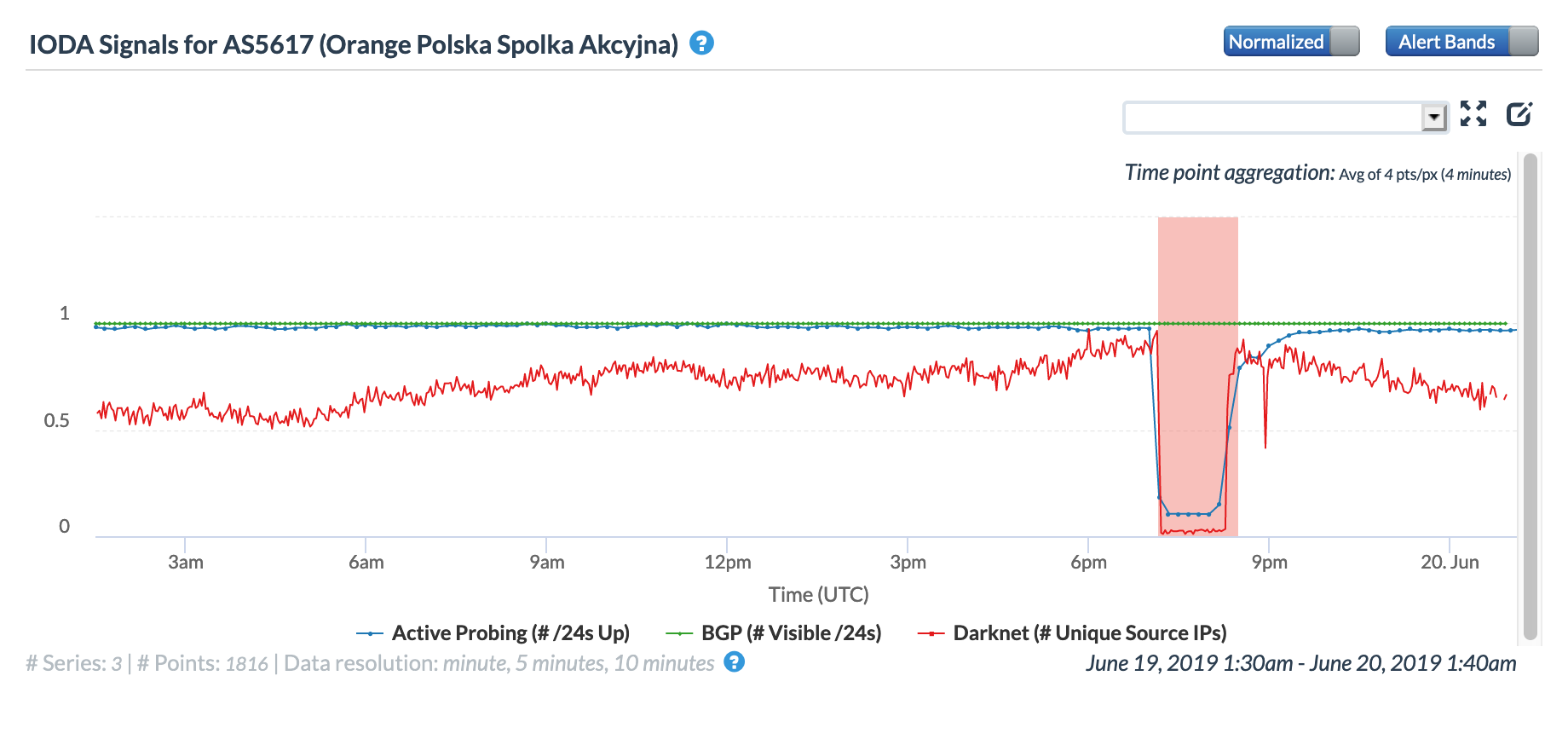

There was some distrust of Togo Telecom’s claim of a technical problem, given Togo’s history of Internet shutdowns and the fact that this issue occurred exactly a month before an election. However, the Oracle and CAIDA figures below show that an Internet disruption of extremely similar scope and duration was observed at the same time in Cape Verde, with a disruption in Cameroon also starting at the same time, though it was less significant than the ones in Togo and Cape Verde. Because Cape Verde and Cameroon are also connected to the WACS submarine cable, this would seem to support the claim that there was indeed a problem with the cable.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Cape Verde, January 22-23

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS37517 (Cabo Verde Telecom), January 22-23

CAIDA IODA graph for AS37517 (Cabo Verde Telecom), January 22-23

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Cameroon, January 22-23

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS15964 (CAMTEL), January 22-23

CAIDA IODA graph for AS15964 (CAMTEL), January 22-23

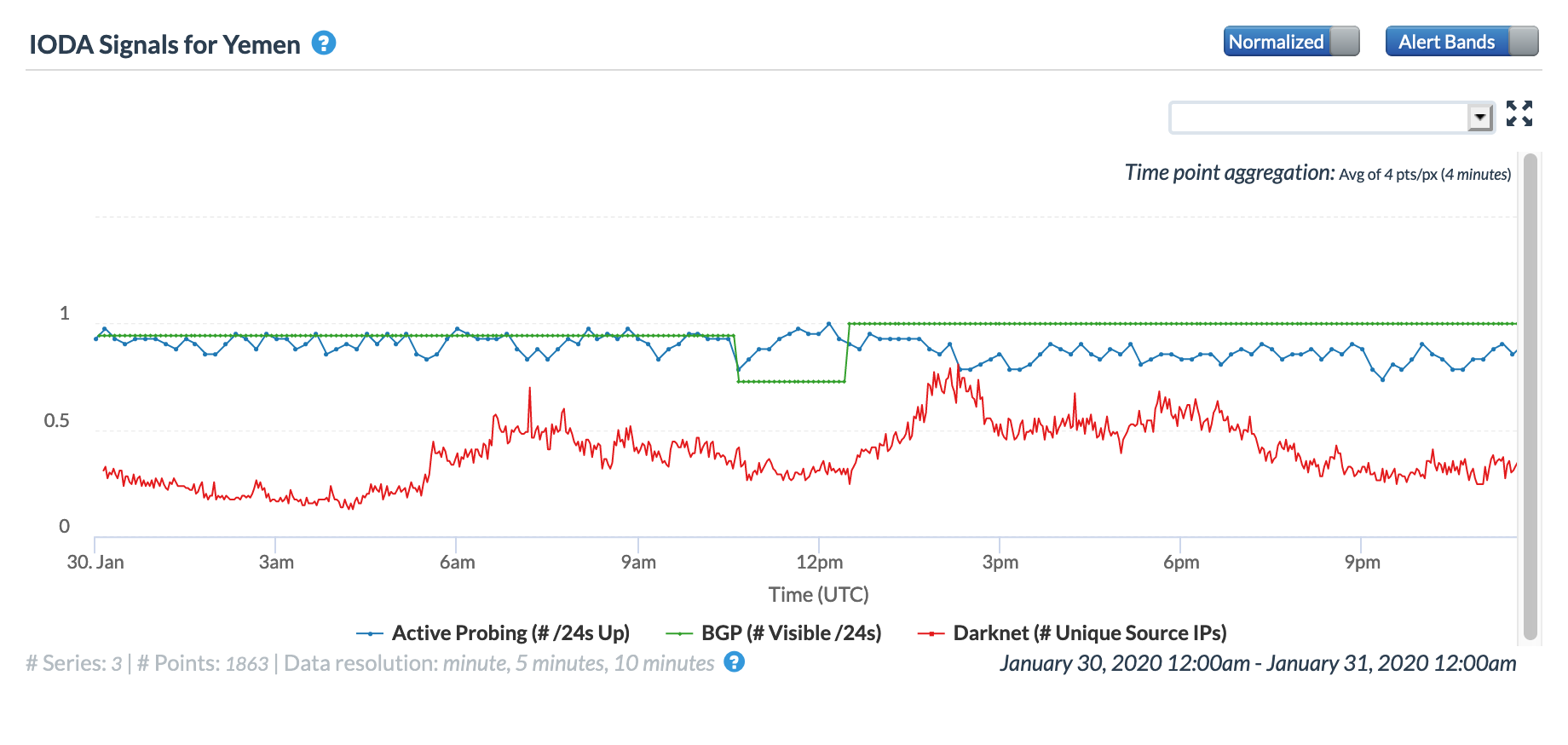

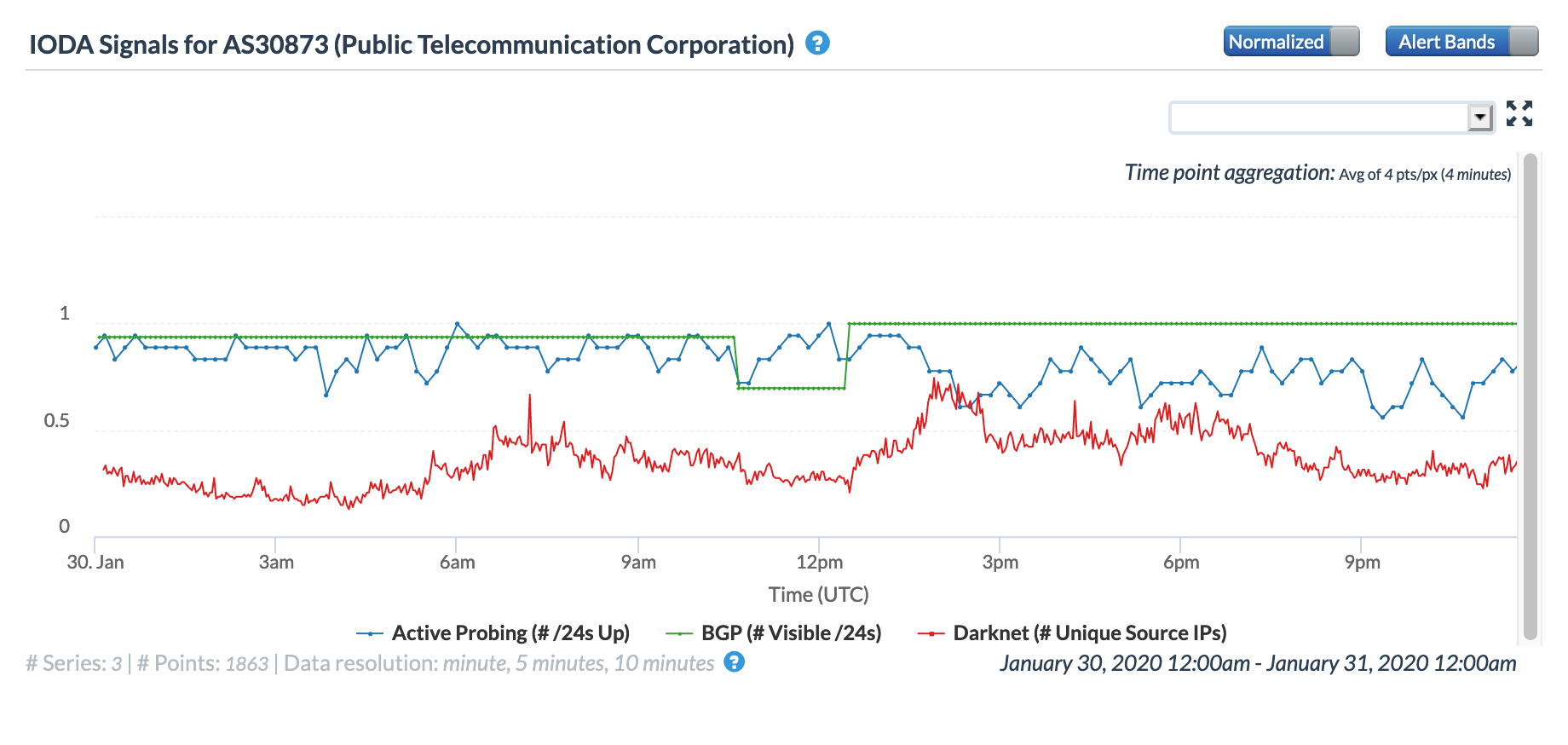

Closing out the month, a brief Internet disruption was observed in Yemen. lasting for several hours during the late morning (GMT) of January 30. The figures below show the impact at a country level, as well as at a network level for AS30873 (YemenNet). Both the Oracle Internet Intelligence and CAIDA IODA graphs show a brief drop in the BGP metric. However, it is interesting to note that while the Oracle graphs show a corresponding drop for active probing, that metric does not decline in the CAIDA measurements. Oddly, it actually appears to improve during the period of disruption, which is unexpected.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Yemen, January 30

CAIDA IODA graph for Yemen, January 30

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS30873 (YemenNet), January 30

CAIDA IODA graph for AS30873 (YemenNet), January 30

According to a published report, the disruption was reportedly caused by a Saudi-led coalition mercenary militia in Aden province storming the international link station and cutting off access to the international Aden-Djibouti cable.

Conclusion

#Kashmir has lost some Rs 1.78 lakh crore ($25 billion) in economic output in the five months since August 2019. This is 11% of the erstwhile state’s nominal gross state domestic product (GSDP) of Rs 1.59 lakh crore for 2018-19. @qzindia https://t.co/75kHirozkl

— InternetShutdowns.in (@NetShutdowns) February 21, 2020

The Internet disruptions covered in this month’s report were all generally short-lived, likely resulting in limited economic impact. However, the Internet shutdown in the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir started in August 2019, and had an estimated impact of USD $25 billion in the five months after in began. However, there are positive signs, as in January, the Indian Supreme court said that an indefinite shutdown of the Internet in Kashmir was illegal. Limited Internet service was restored to the regions in the middle of the month, including broadband in hotels, travel establishments, and hospitals, but with access restricted to white-listed Web sites. 2G mobile connectivity also returned, but was limited to white-listed Web sites as well.

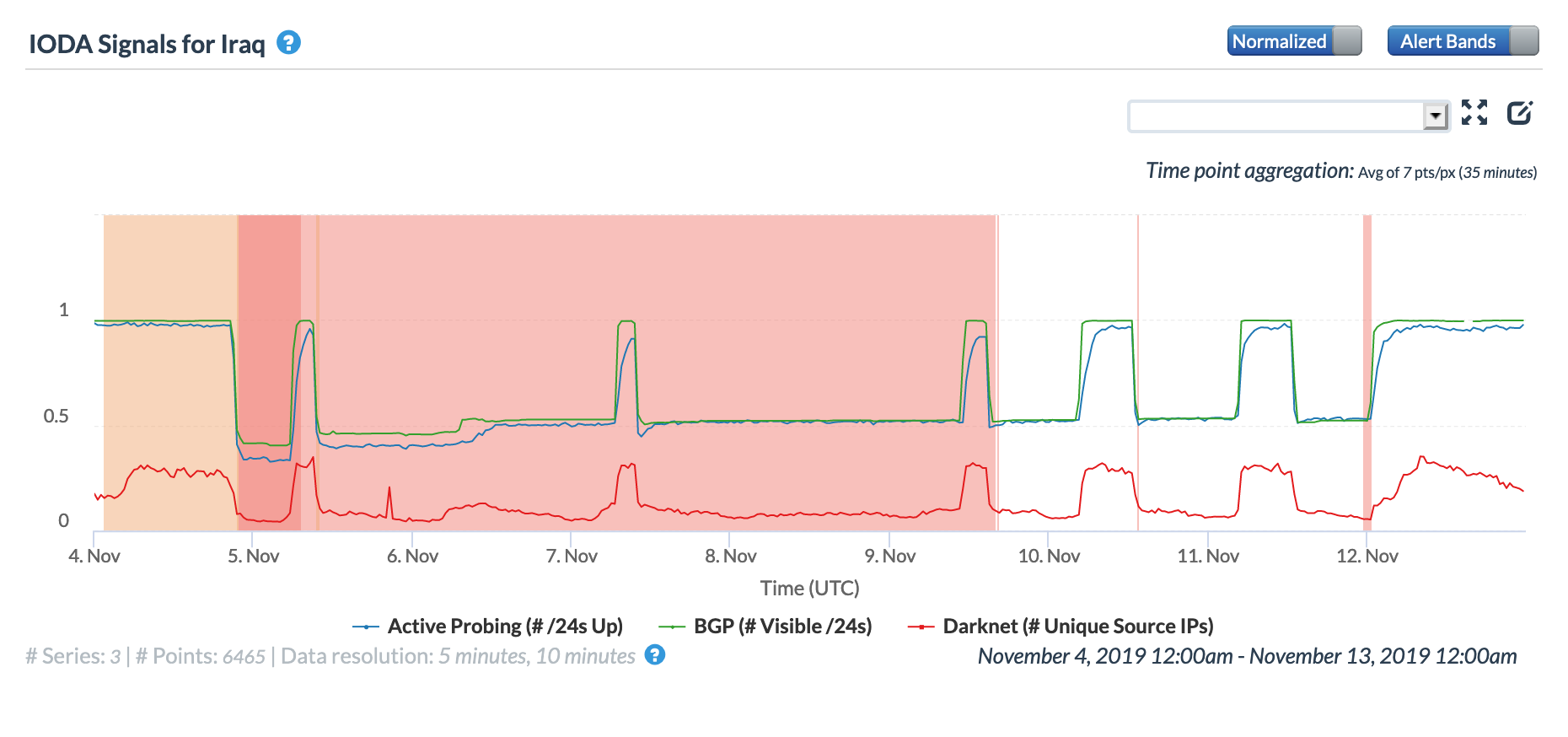

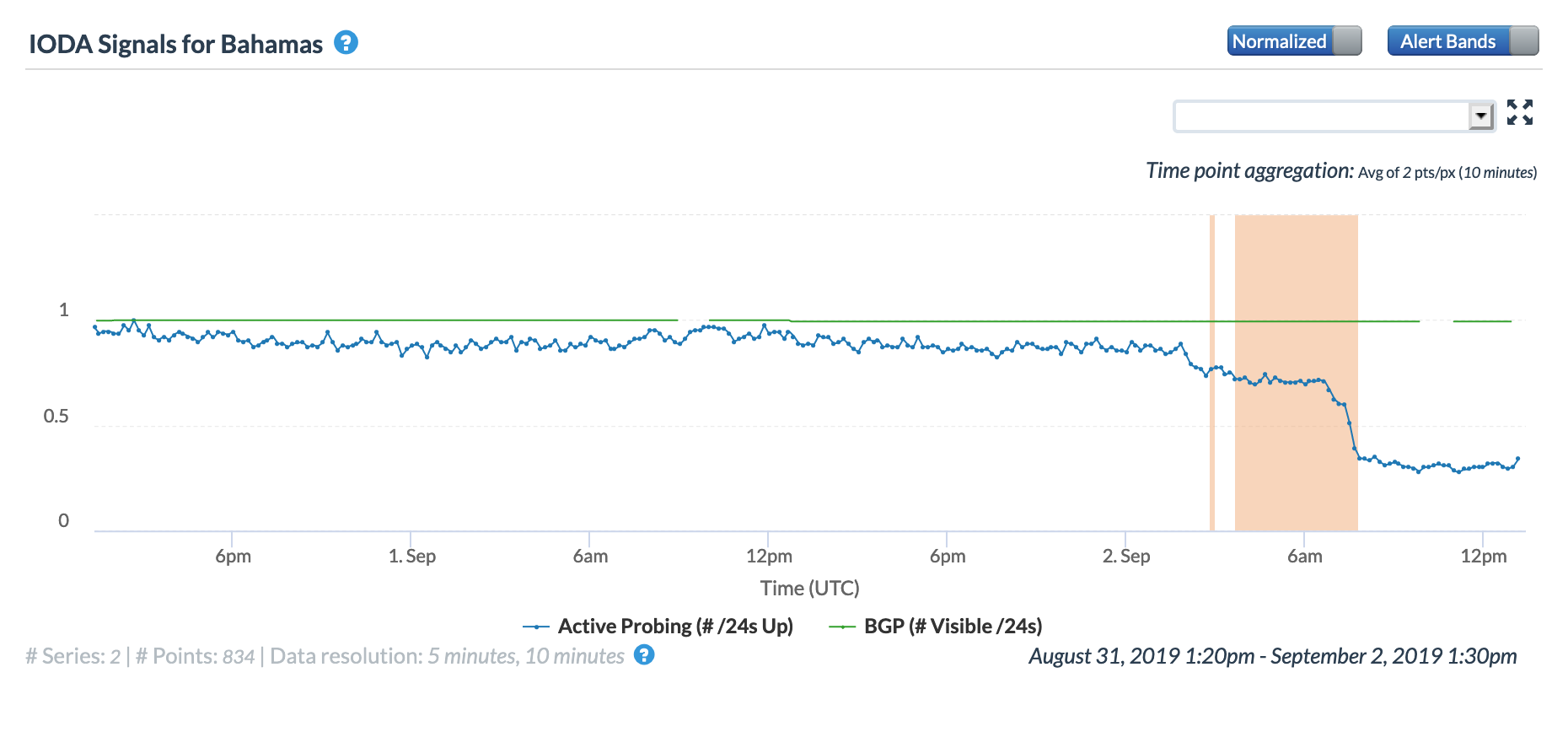

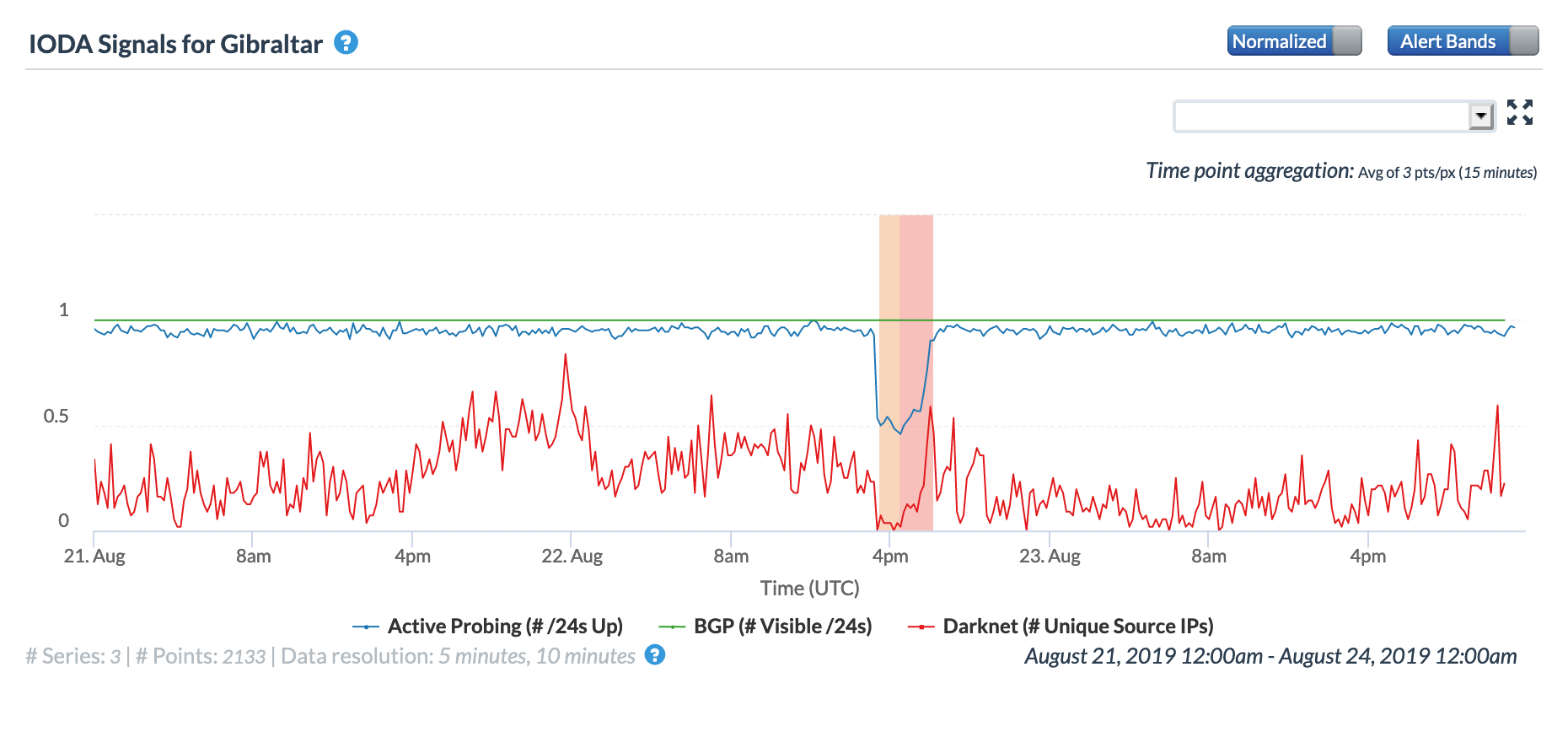

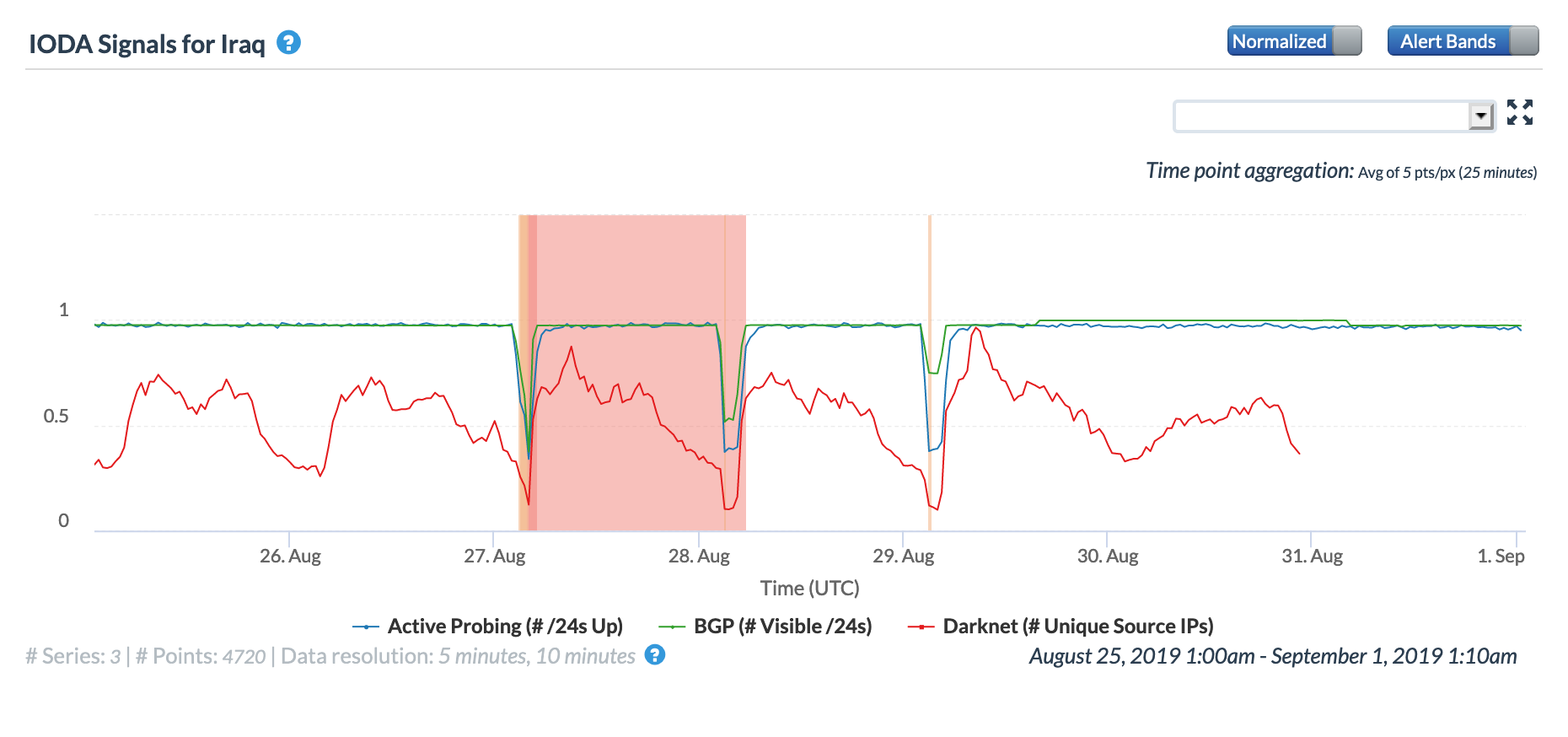

]]>This final Internet Disruption Report post for 2019 is a long one, covering disruptions caused by a DDoS attack, power outages, cable/fiber/network issues, and government direction. Some countries make multiple appearances in this month’s report, and some have been featured in multiple reports throughout the year. In addition to observed disruptions, we also review Russia’s reported Internet disconnection test, as well as a few additional related observations.

DDoS Attack

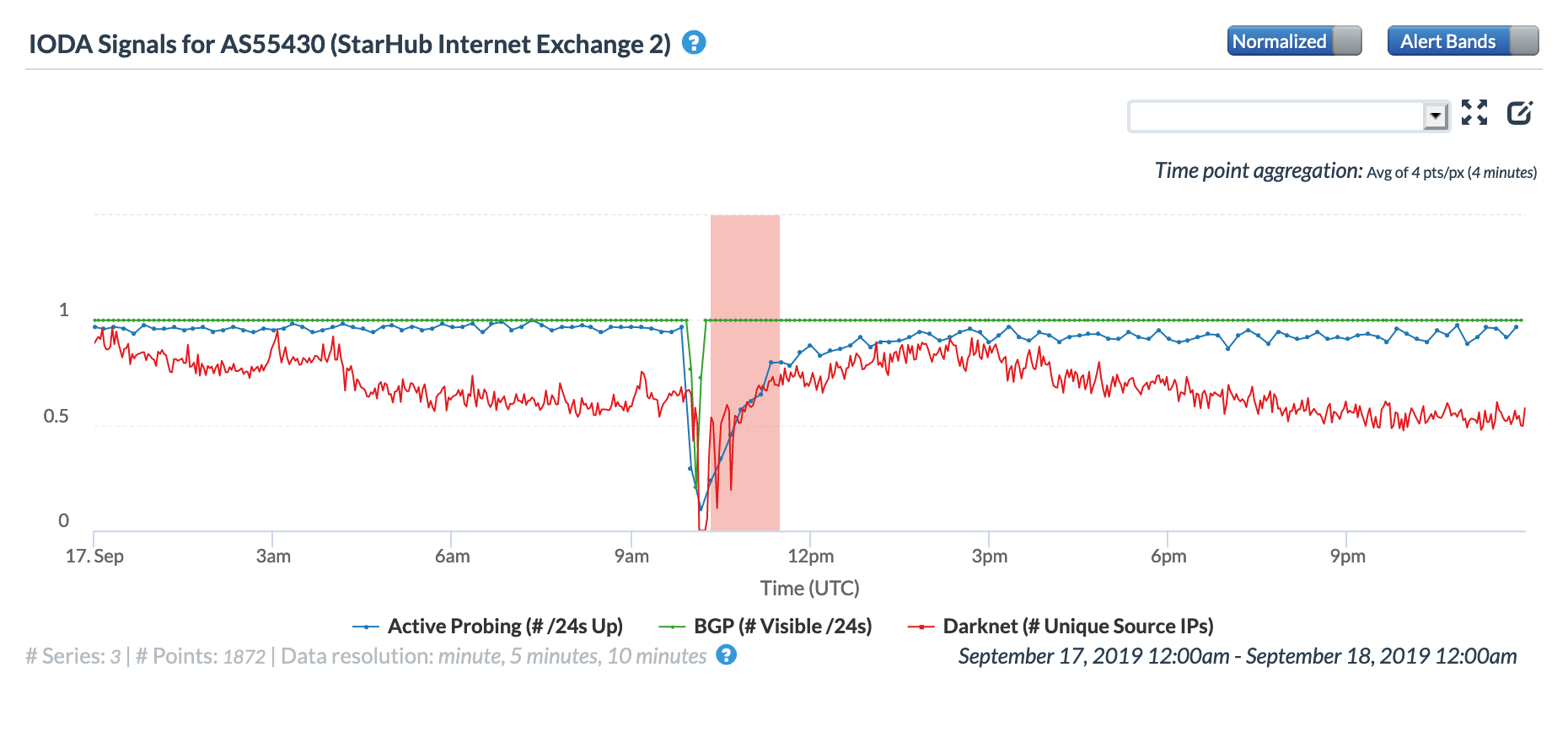

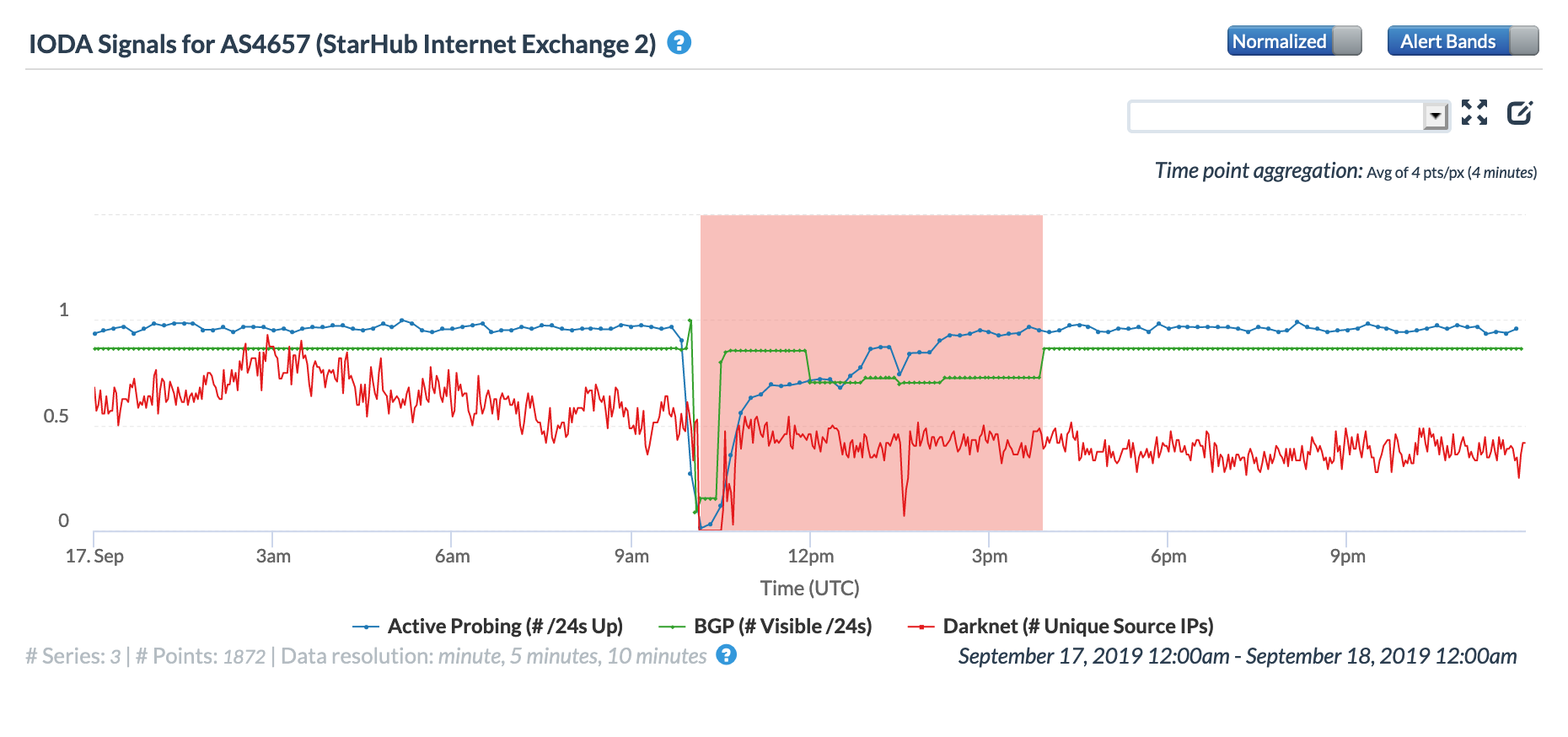

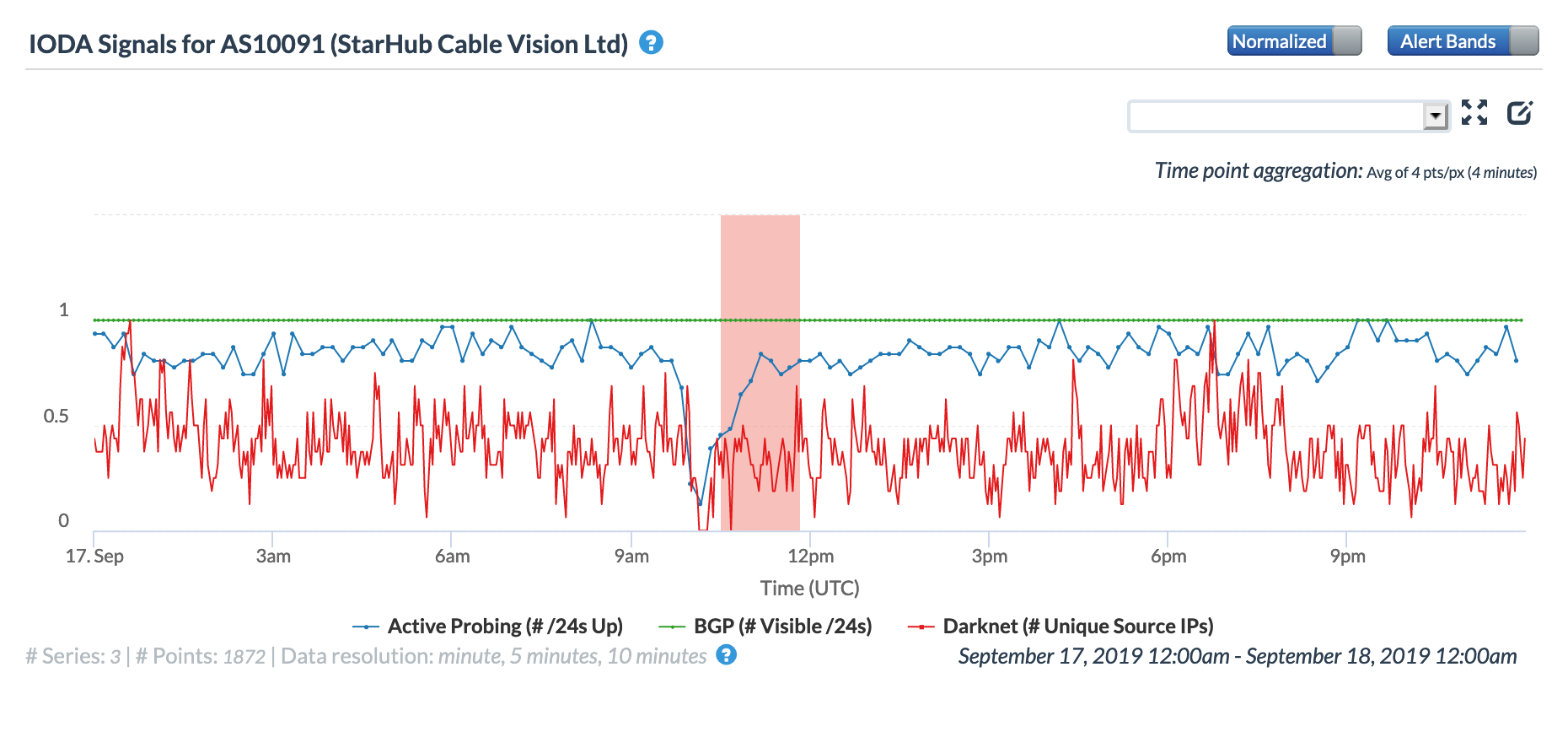

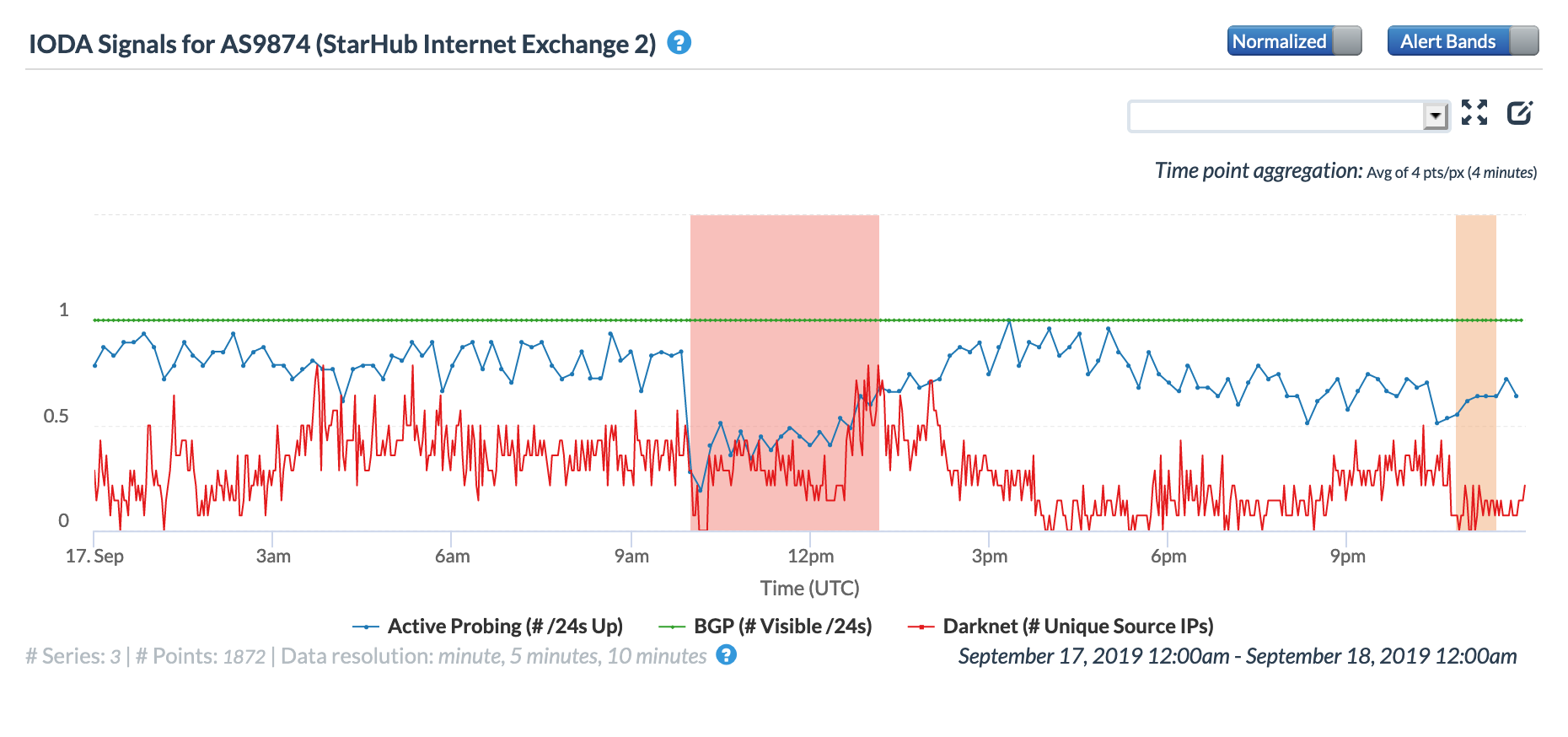

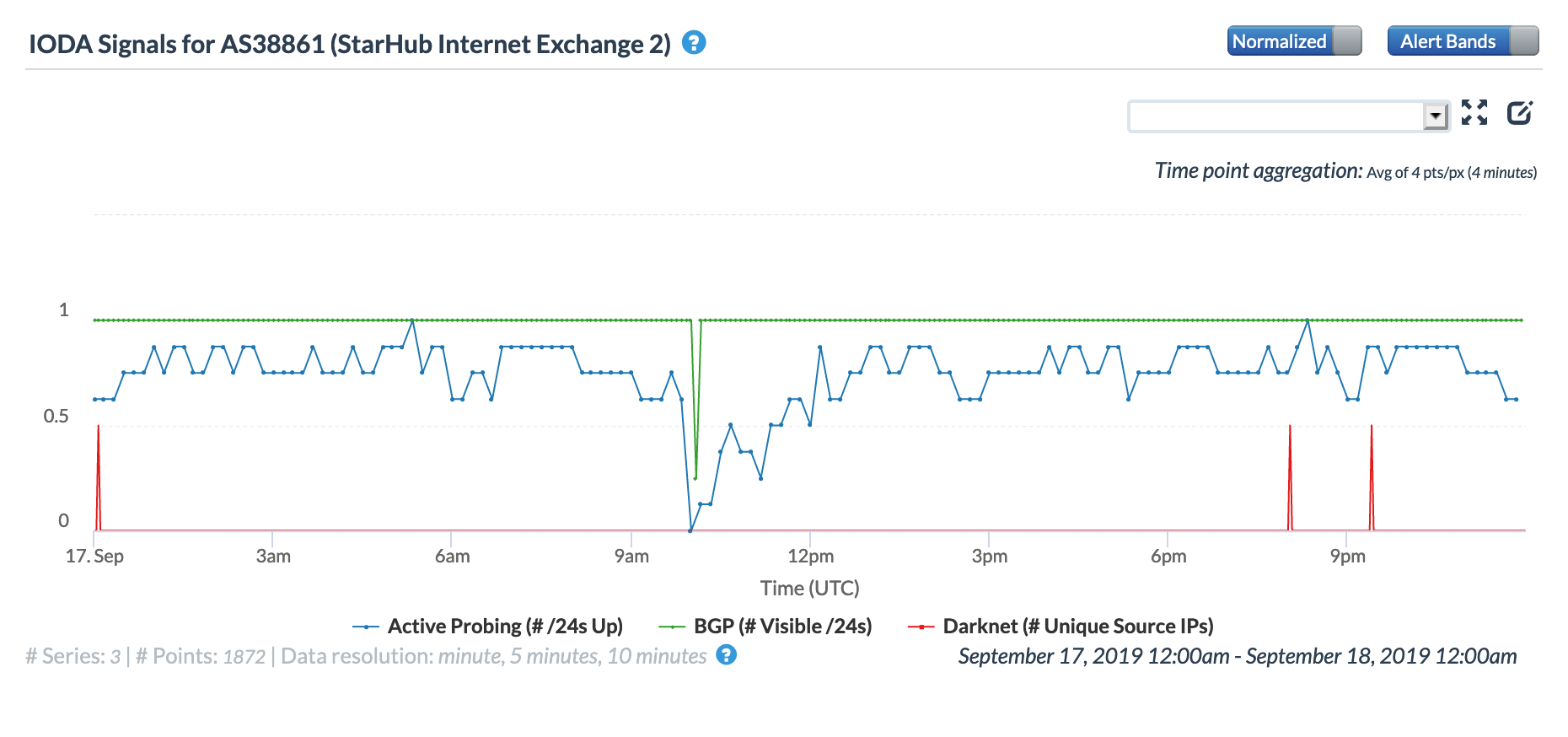

Three months after a DDoS attack in September caused an Internet disruption at South African provider Cool Ideas, another DDoS attack targeting the provider again impacted connectivity. As shown in the Fing Internet Alerts and CAIDA IODA figures below, the attack appears to have occurred in several waves, with the first starting around 0815 GMT, lasting for approximately two hours, and the second starting around 1200 GMT, lasting for just over an hour.

Recognizing the problems that these attacks create for local providers, a published report highlighted how South Africa plans to fight similar DDoS attacks in the future:

South Africa’s Internet Service Providers’ Association (ISPA) has said that in an attempt to mitigate the severity of DDoS attacks against local ISPs, administrators at South Africa’s Internet exchanges are creating a “blackhole” that will funnel identified DDoS traffic through the exchanges into oblivion.

Power Outages

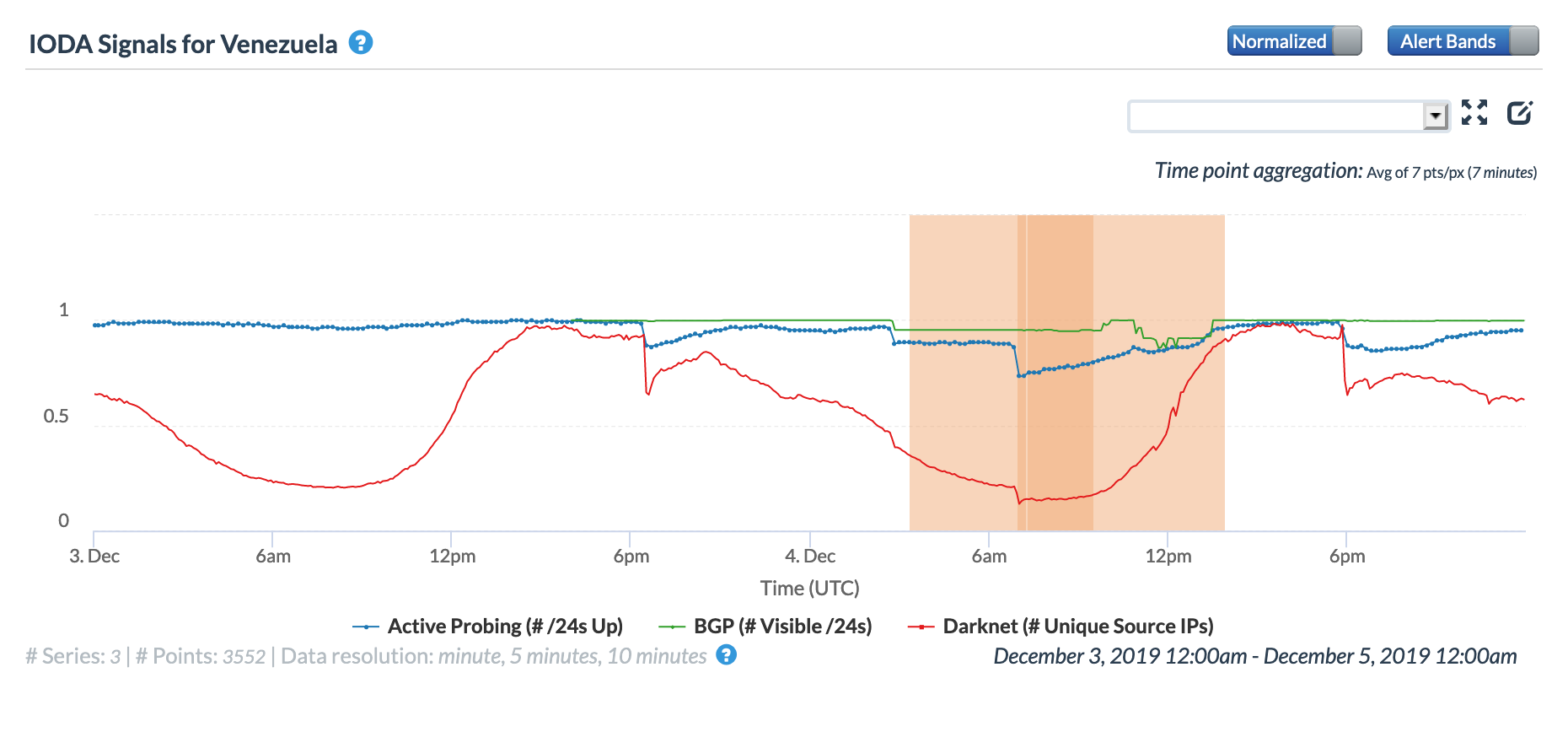

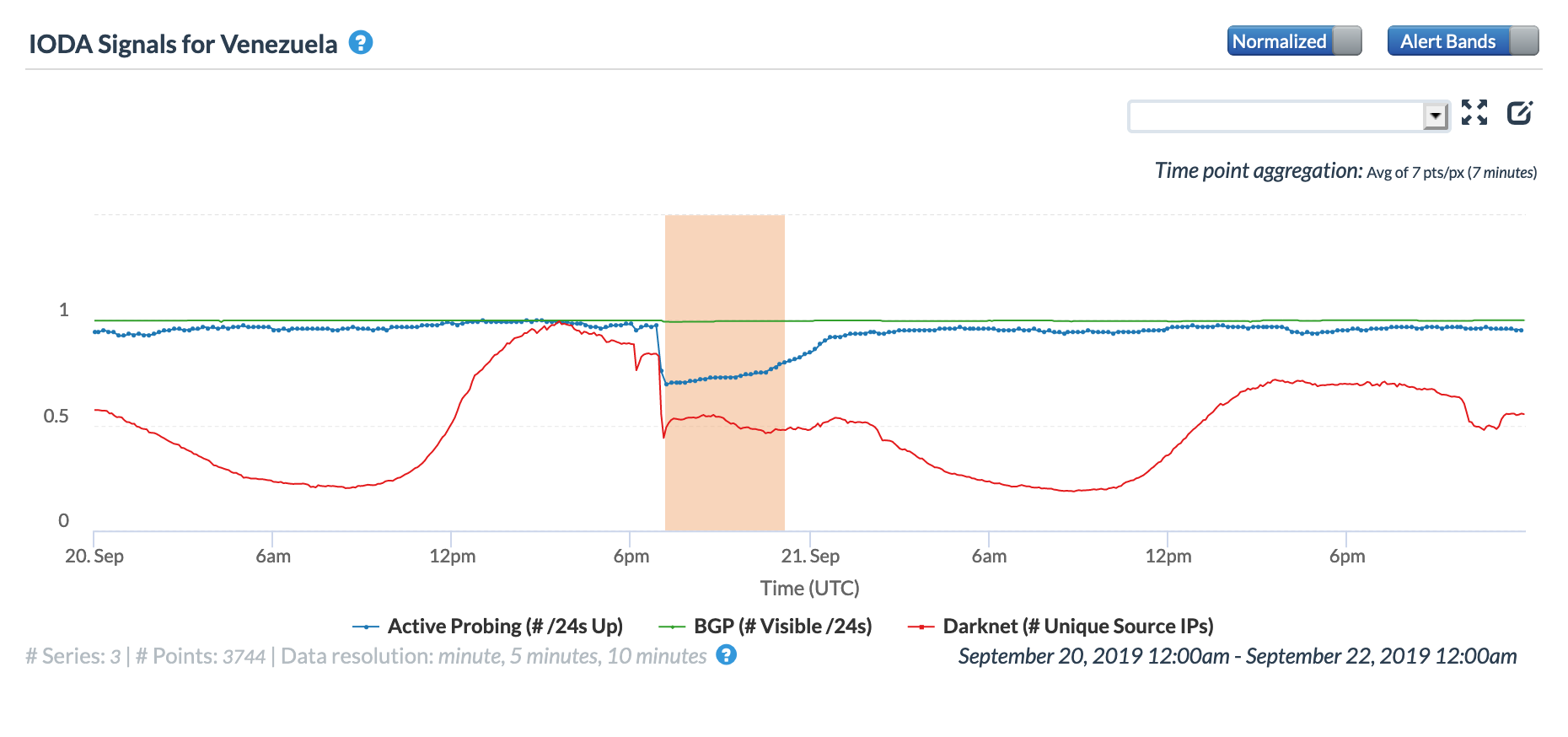

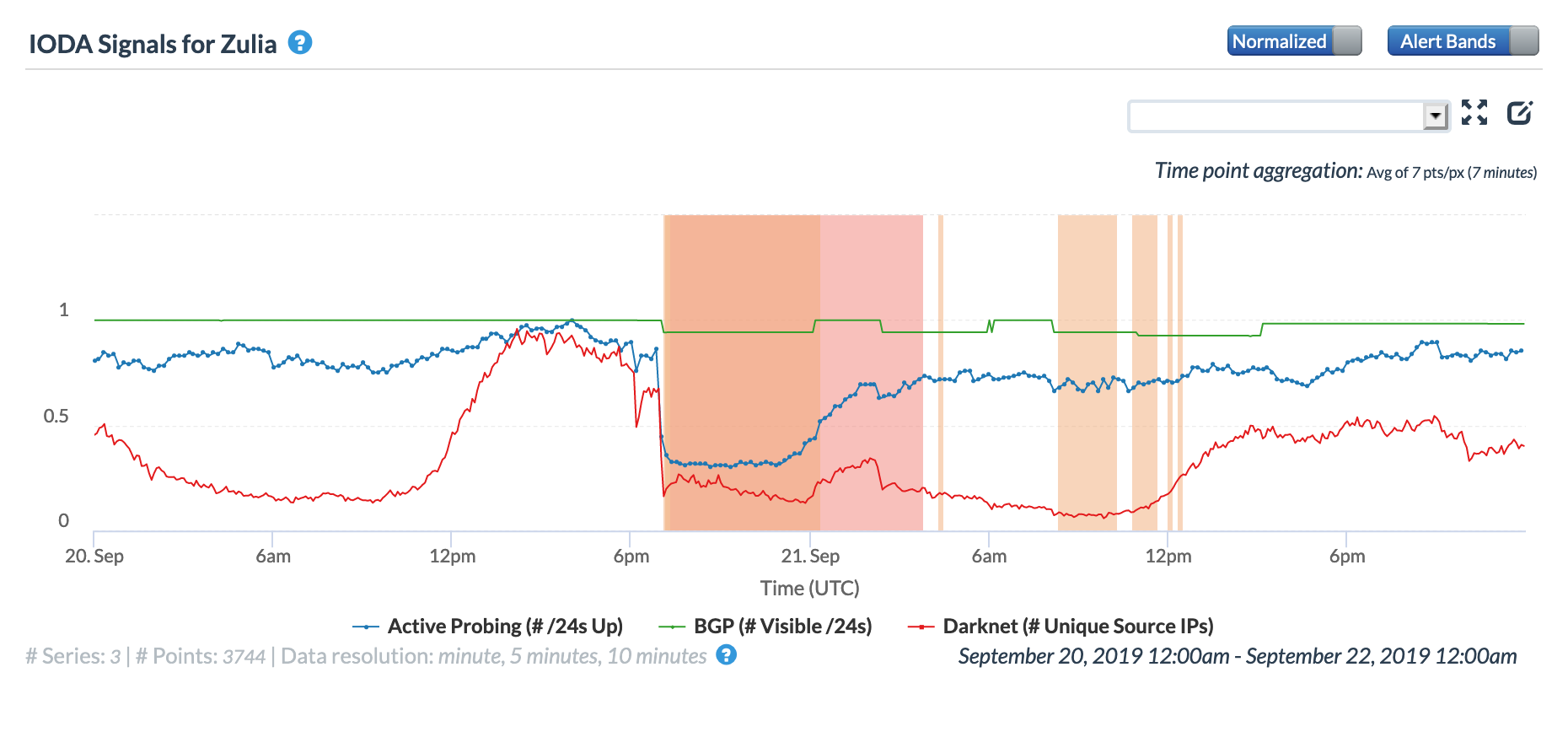

On December 4, NetBlocks posted a Tweet confirming that the third major power outage in Venezuela in just two days had disrupted Internet connectivity across multiple states. These disruptions are visible at a country level in the figures below, apparently occurring around 1830 GMT on December 3, 0645 GMT on December 4, and 1800 GMT on December 4.

A Tweet from @CorpoElecInfo (the Twitter account of Venezuela’s national electric company) that afternoon referenced system recovery efforts, presumably associated with the power outage.

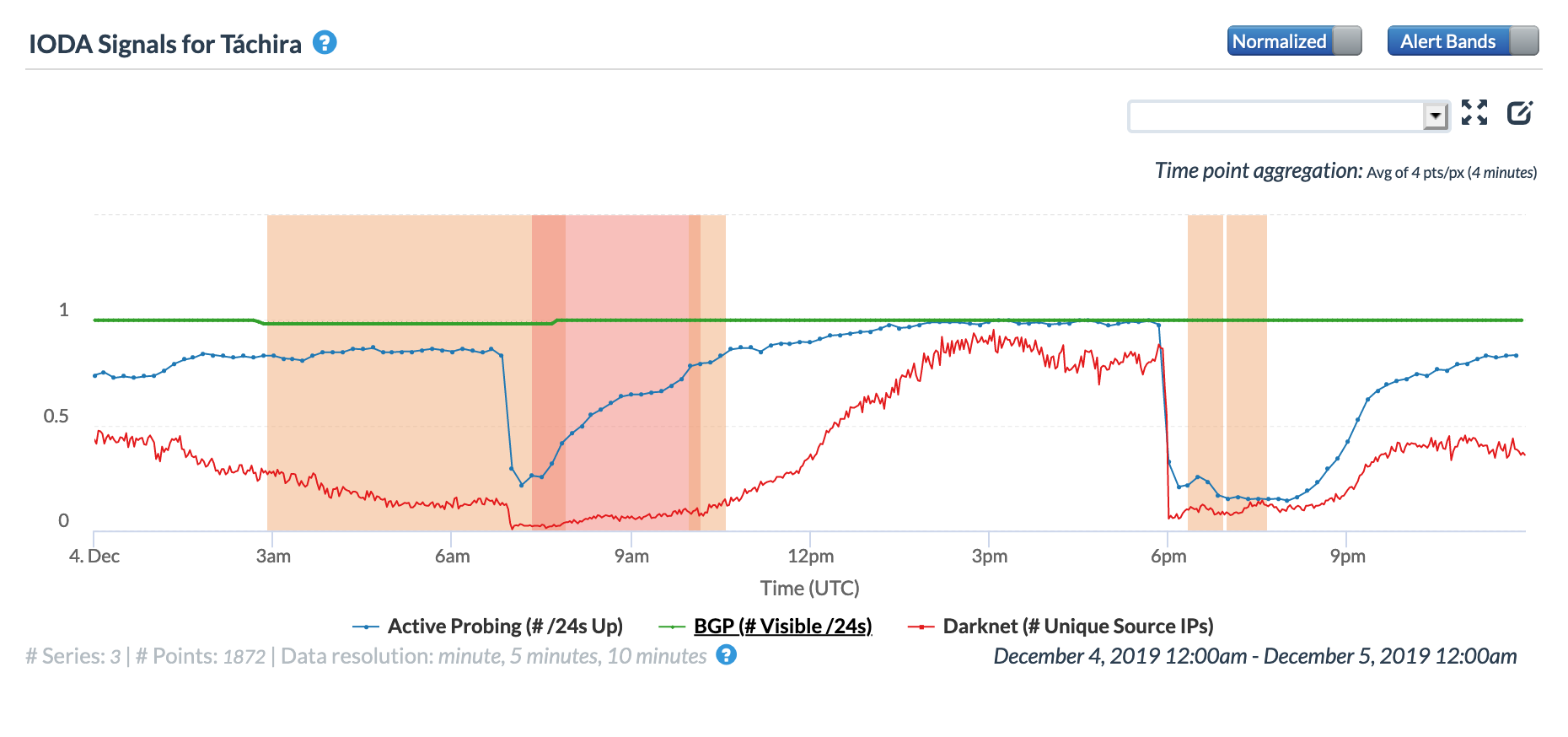

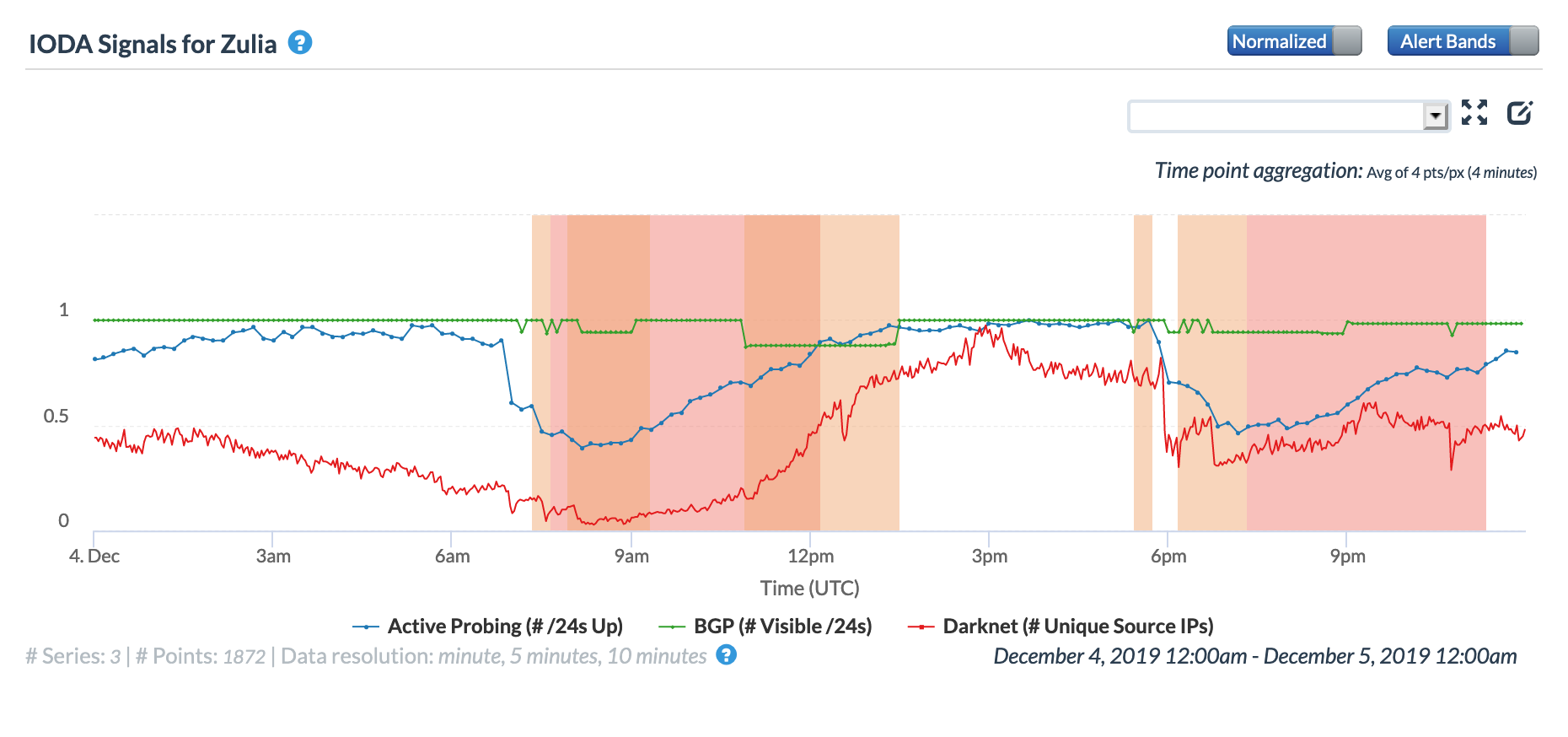

NetBlocks listed fifteen Venezuelan state where Internet connectivity was disrupted by the power outage, and the figures below show the impact on three of those states. In Tachira and Zulia, the 0645 and 1800 GMT disruptions are clearly visible. However, in Aragua, there is a significant disruption evident starting around 0300 GMT that lasted over six hours – this could potentially be related to a more severe, localized power outage. The 1800 GMT disruption is visible for Aragua as well, although the impact is lower than was seen for Tachira and Zulia.

CAIDA IODA graph for Aragua, Venezuela, December 4

CAIDA IODA graph for Tachira, Venezuela, December 4

CAIDA IODA graph for Zulia, Venezuela, December 4

CAIDA IODA also observed Internet disruptions in Venezuelan states including Aragua, Cojedes, and Guárico on December 29. However, there was no publicly available information associating these disruptions with a power outage event. (But they are highlighted here because of the frequency of power outage-caused Internet disruptions in Venezuela.)

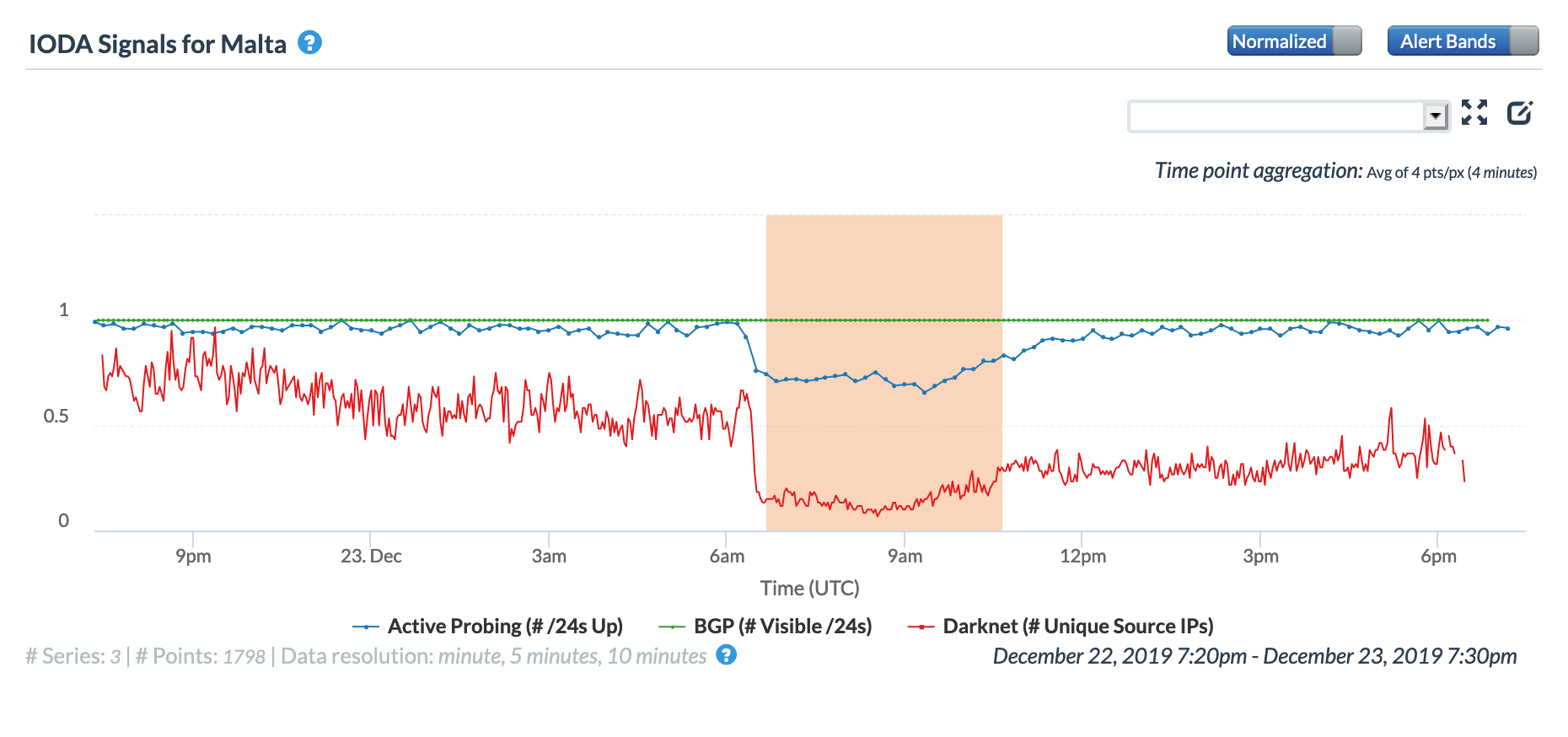

Just two days before Christmas, a nationwide power outage struck the island nation of Malta, reportedly caused by a fault on the interconnector cable between Malta and Sicily. As illustrated in the Oracle and CAIDA IODA figures below, the Internet disruption caused by this power outage started around 0600 GMT, with connectivity gradually returning to normal after noon GMT. The Google Transparency Report figure below shows the impact that the disruption had on traffic from Malta to Google’s GMail application, with a significant decline seen between 0600-0630 GMT, and a clear recovery visible six hours later.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Malta, December 23

CAIDA IODA graph for Malta, December 23

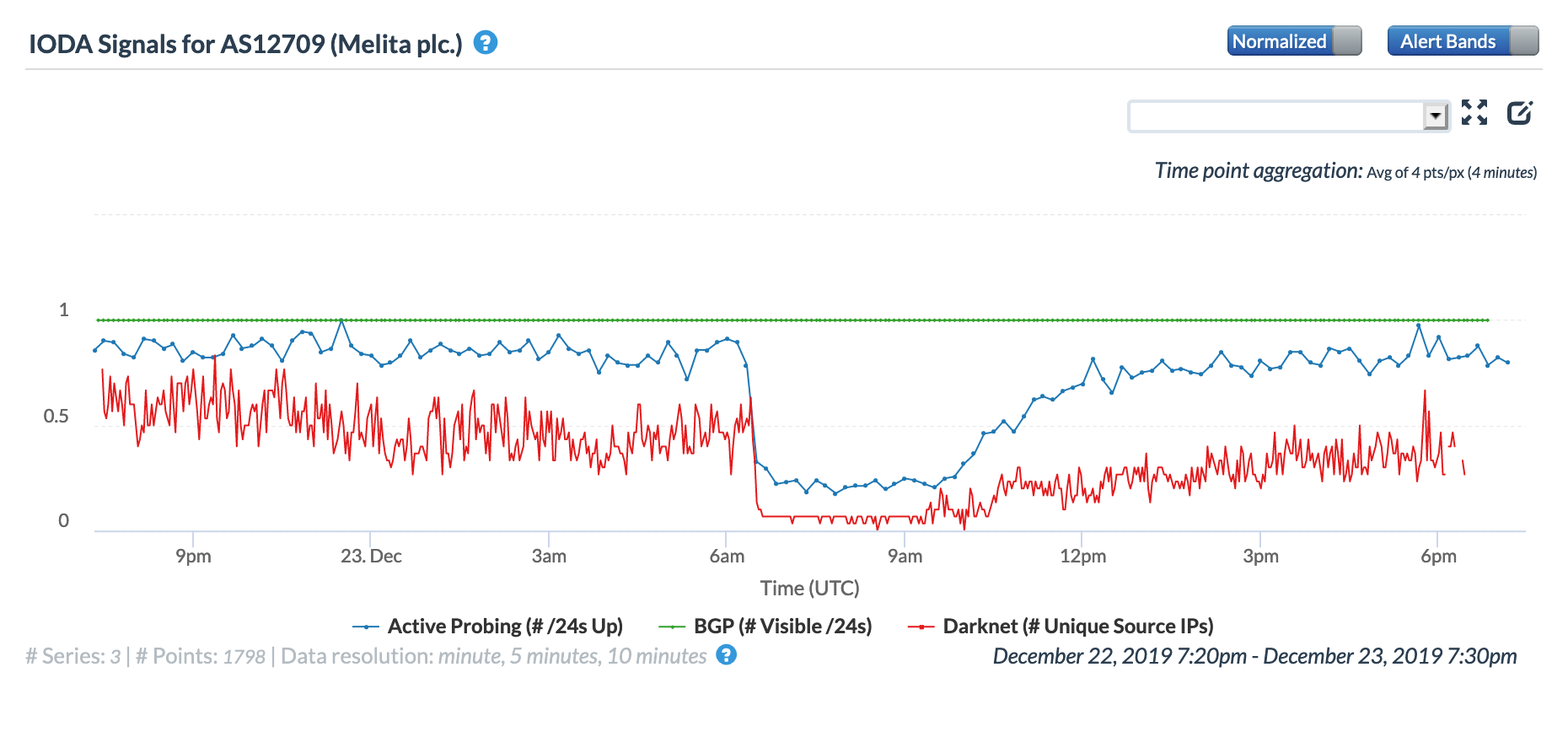

Melita, a major telecommunications provider in Malta, provided status updates to its customers via its Facebook page. The figures below show the power outage’s impact to Melita’s network, with the Fing Internet Alerts graph showing a complete loss of communication with local probes. The Oracle and CAIDA IODA graphs show a significant decline in the active probing metrics, and the CAIDA IODA graph shows the relative volume of Darknet source IPs in that network dropping to near zero, in line with Fing’s observation of an end-user connectivity outage.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS12709 (Melita), December 23

CAIDA IODA graph for AS12709 (Melita), December 23

Cable/Fiber Cuts & Network Issues

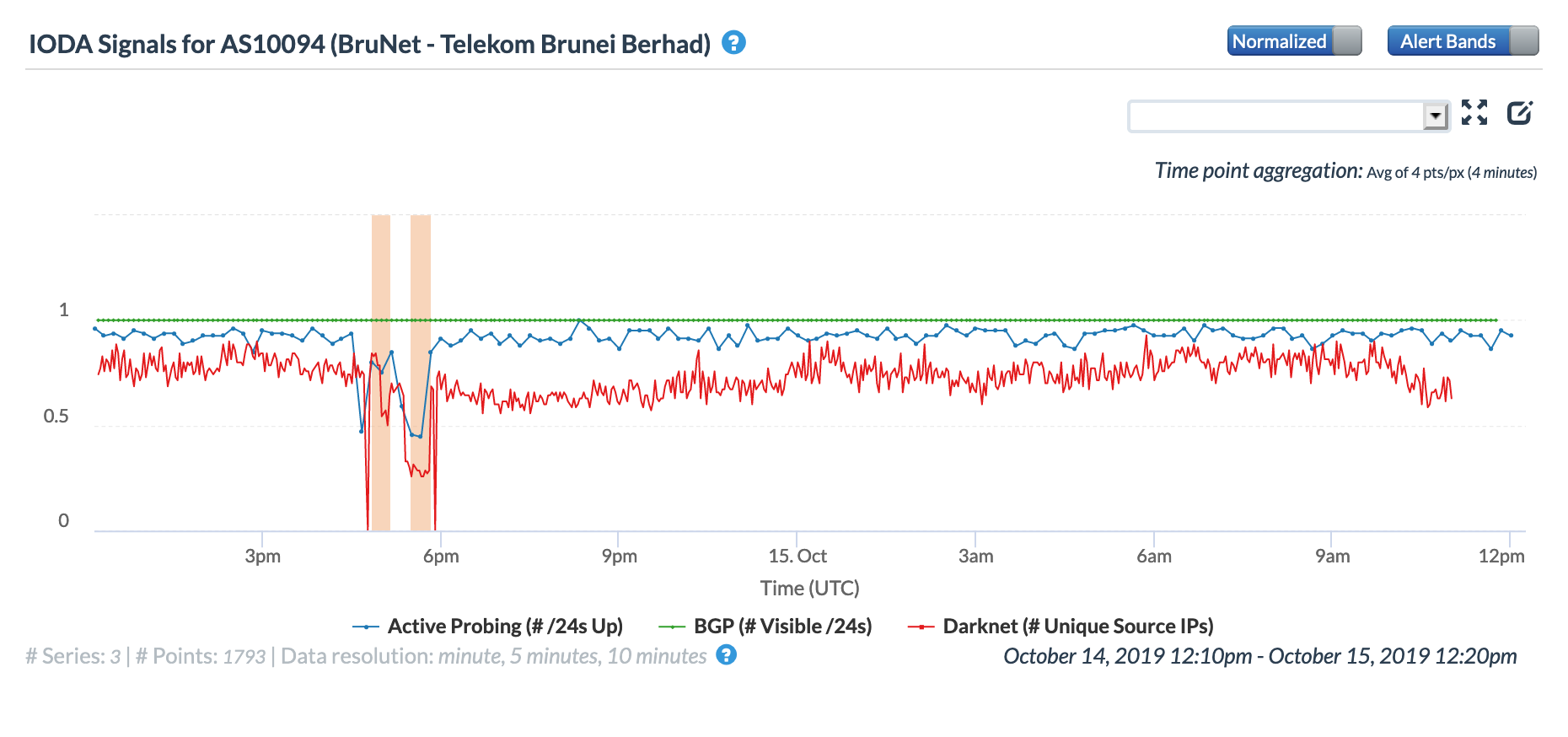

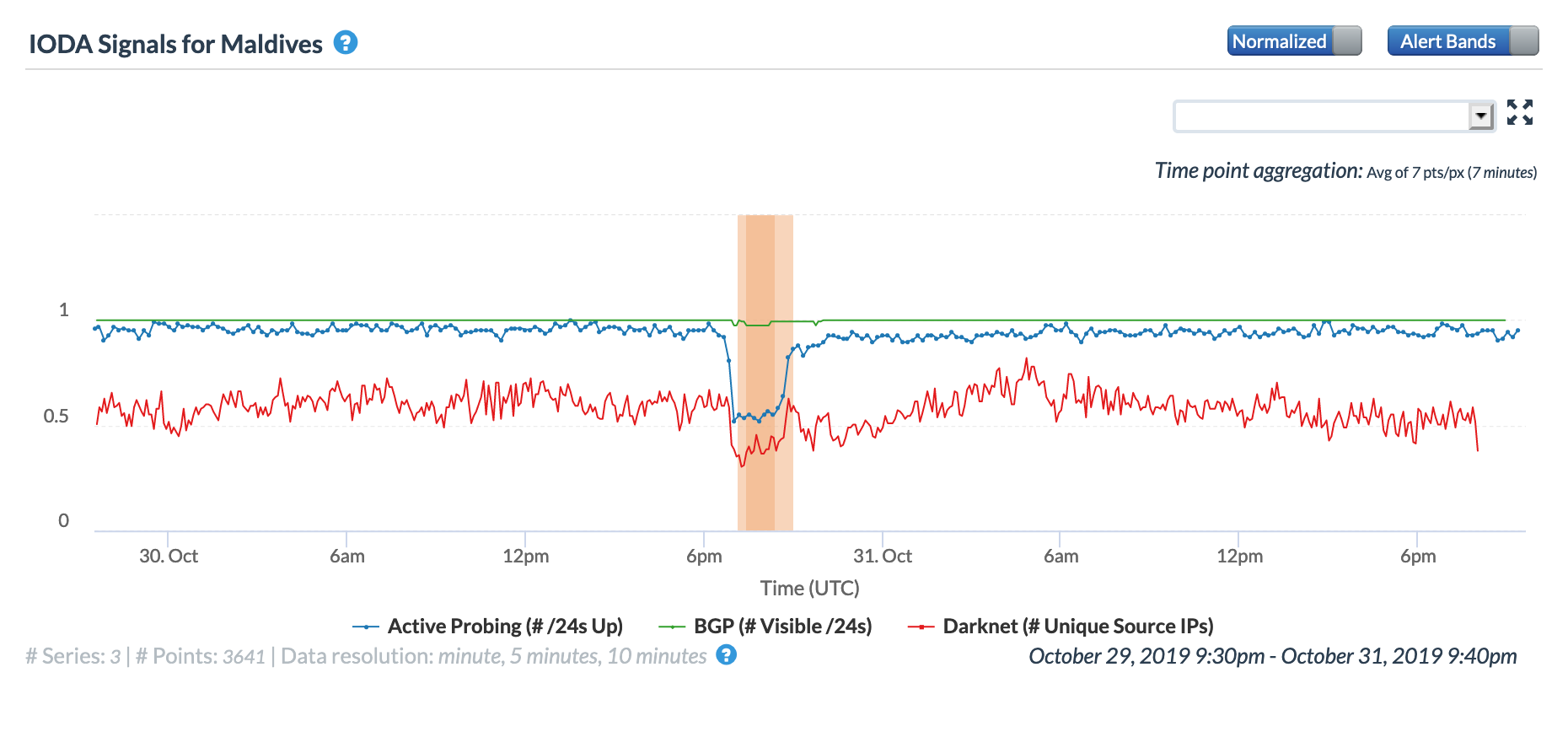

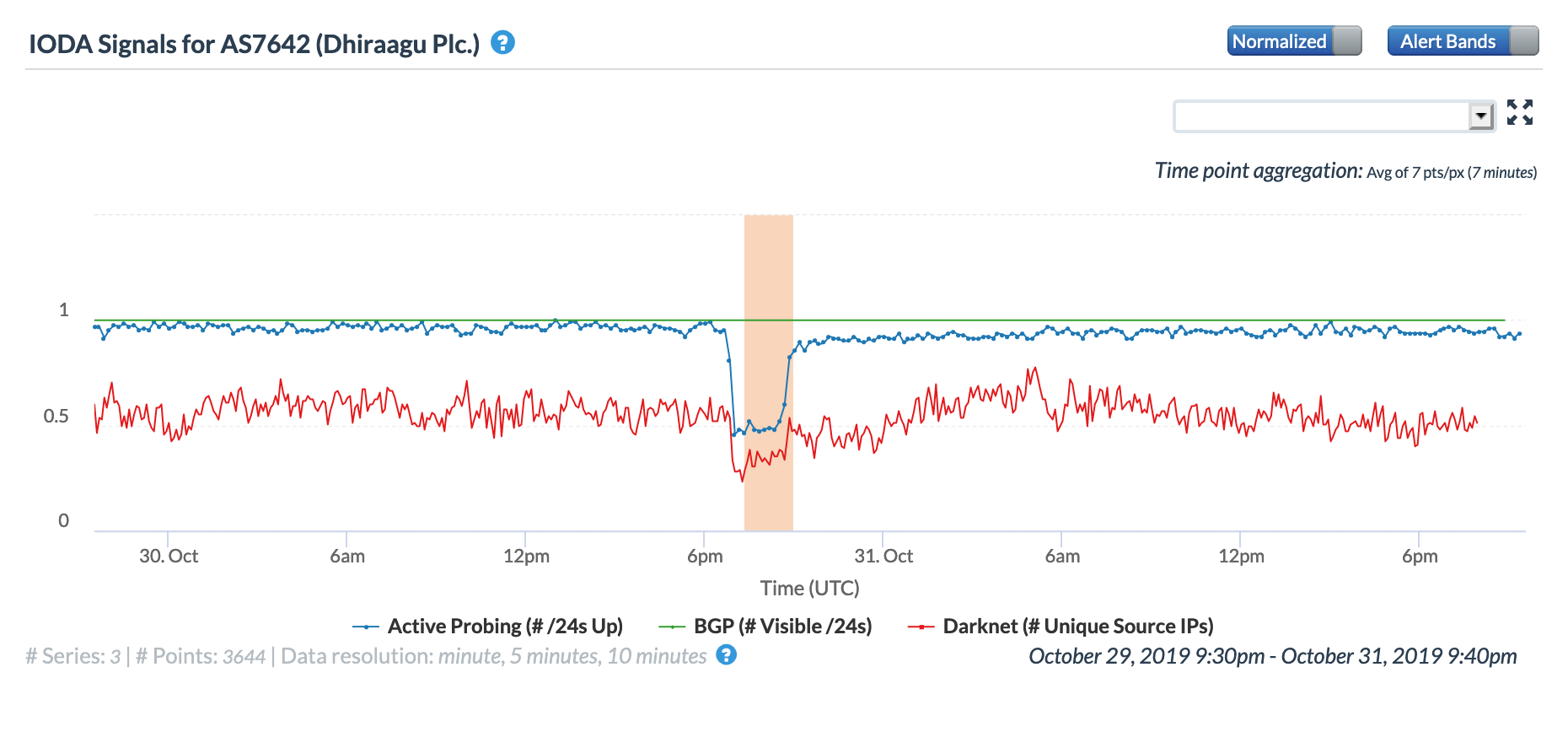

Late in the day (GMT) on November 30, Dhiraagu, the largest network service provider in the Maldives, posted an update to its Facebook page alerting customers to “unexpected technical issues” on its fixed broadband network. The impact of these issues lasted into December 1, and were visible at both a country and network level. The Oracle and CAIDA IODA figures below show that active probing measurements to endpoints in the country declined just before midnight (GMT), and started to recover approximately eight hours later.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for the Maldives, December 1

CAIDA IODA graph for the Maldives, December 1

The figures below illustrate the impact on one of Dhiraagu’s autonomous systems. The Oracle graph shows that latency for traceroutes to endpoints within the network increased significantly during the period of disruption. Although Dhiraagu posted a second Facebook update a little more that five hours after the first one alerting subscribers that the issue had been fully resolved, it is clear that connectivity took several additional hours to return to “normal” levels.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS7642 (Dhiraagu), December 1

CAIDA IODA graph for AS7642 (Dhiraagu), December 1

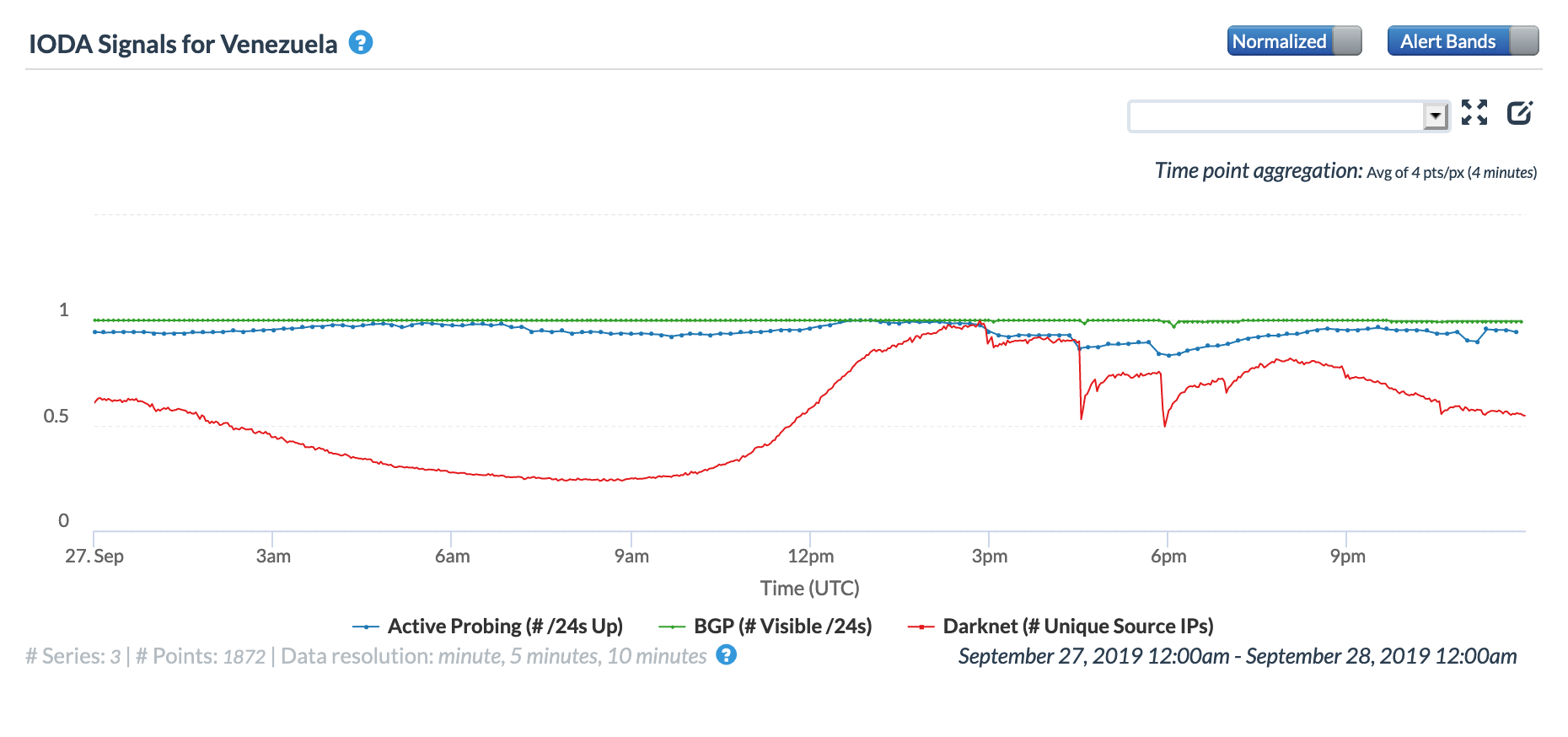

On December 1, NetBlocks reported that planned maintenance to a submarine cable disrupted Internet connectivity for multiple network providers in Venezuela. Several of these providers had alerted subscribers via Twitter that this maintenance would be taking place, apologizing in advance for the inconvenience that the lack of Internet connectivity would cause.

El cable submarino privado principal que conecta nuestro país con el resto del mundo, tendrá un mantenimiento programado el día de mañana, 01 de diciembre, desde las 8:00 a.m. hasta las 3:00 p.m.

— InterCliente (@InterCliente) November 30, 2019

#ATENCIÓN

— Movistar Venezuela (@MovistarVe) November 30, 2019

Mañana 1 de diciembre, de 8:00 am a 3:00 pm, nuestro proveedor de acceso a los servicios de internet estará realizando un mantenimiento programado para reparar una falla del cable submarino

The Internet disruption caused by the submarine cable maintenance is clearly visible at a country level, as seen in the figures below. Both Oracle and CAIDA IODA observed notable declines in the Traceroute Completion/Active Probing and BGP metrics, but it is interesting to note that there was no apparent impact to the traffic-derived metrics, which may indicate that traffic took advantage of alternative paths to exit the country. And although the Tweets from the network providers indicated that the maintenance window was expected to last from 0800 to 1500 local time (1200 to 1900 GMT), it appears that it took longer than expected, with connectivity being restored closer to 1800 local time (2200 GMT).

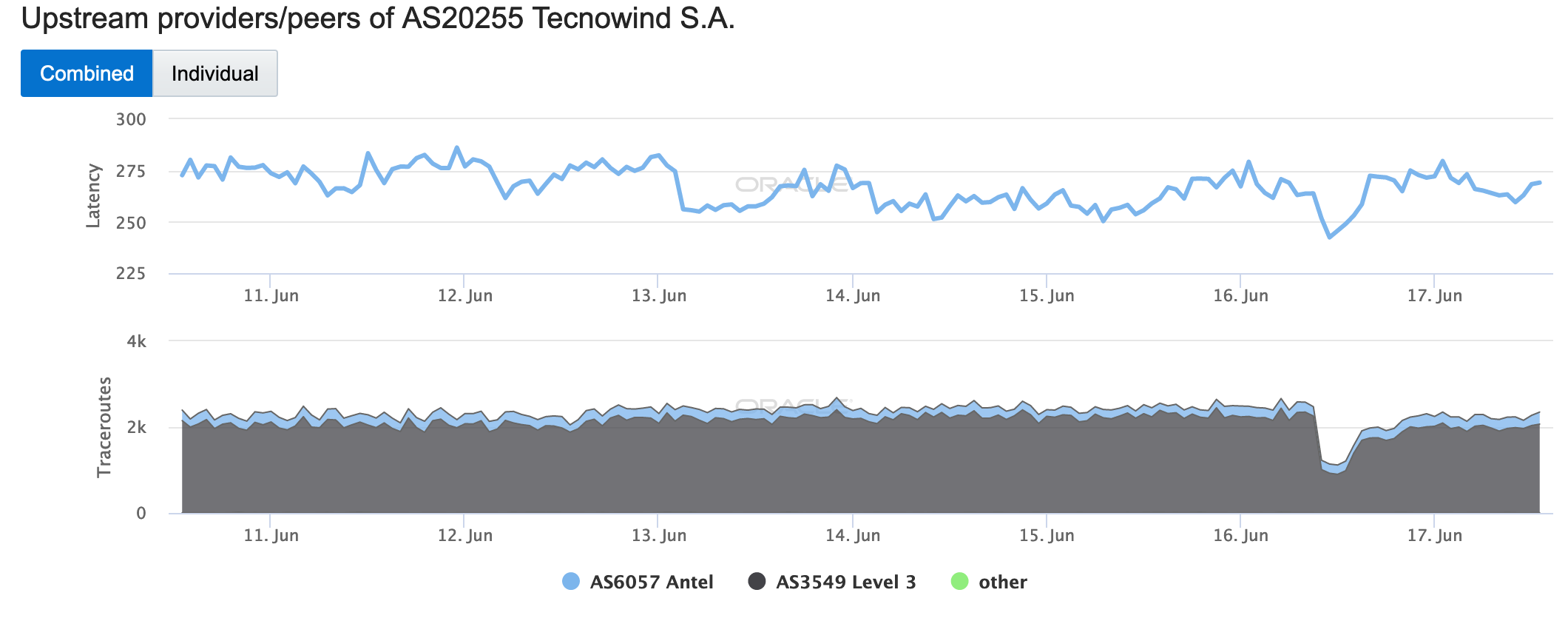

The figures below show the impact of the cable maintenance at a network level, illustrating the Internet disruptions experienced by four Venezuelan Internet service providers: NetLink América, Inter/Corporación Telemic, Net Uno, and Movistar/Telefónica. The Oracle graphs show that during the maintenance window, traceroutes to targets in these networks via AS3549 (Level 3) failed to complete. In some cases (Inter, Net Uno), a smaller percentage of them transited AS52320 (GlobeNet), while for Movistar, other networks picked up the slack.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS263703 (NetLink América), December 1

CAIDA IODA graph for AS263703 (NetLink América), December 1

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS21826 (Inter), December 1

CAIDA IODA graph for AS21826 (Inter), December 1

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS11562 (Net Uno), December 1

CAIDA IODA graph for AS11562 (Net Uno), December 1

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS6306 (Movistar), December 1

CAIDA IODA graph for AS6306 (Movistar), December 1

Although the cable that was being repaired wasn’t specifically named, clues in the CenturyLink memo in the Tweet shown below would seem to indicate that it was the South American Crossing (SAC) cable system. This particular cable is one of two that lands in Panama and St. Croix, as well as Venezuela, but is the only one that has a Panama to St. Croix segment, as referenced in the memo. In addition, CenturyLink is one of the owners of the SAC cable system.

Debido a reparaciones en el cable submarino Panama-St Croix, Proveedores de Servicio de Internet como @InterCliente y @MovistarVe han informado que mañana #1dic será interrumpido el servicio desde las 8:00am hasta las 3:00pm pic.twitter.com/TDIi8mu4ty

— RedesAyuda (@RedesAyuda) December 1, 2019

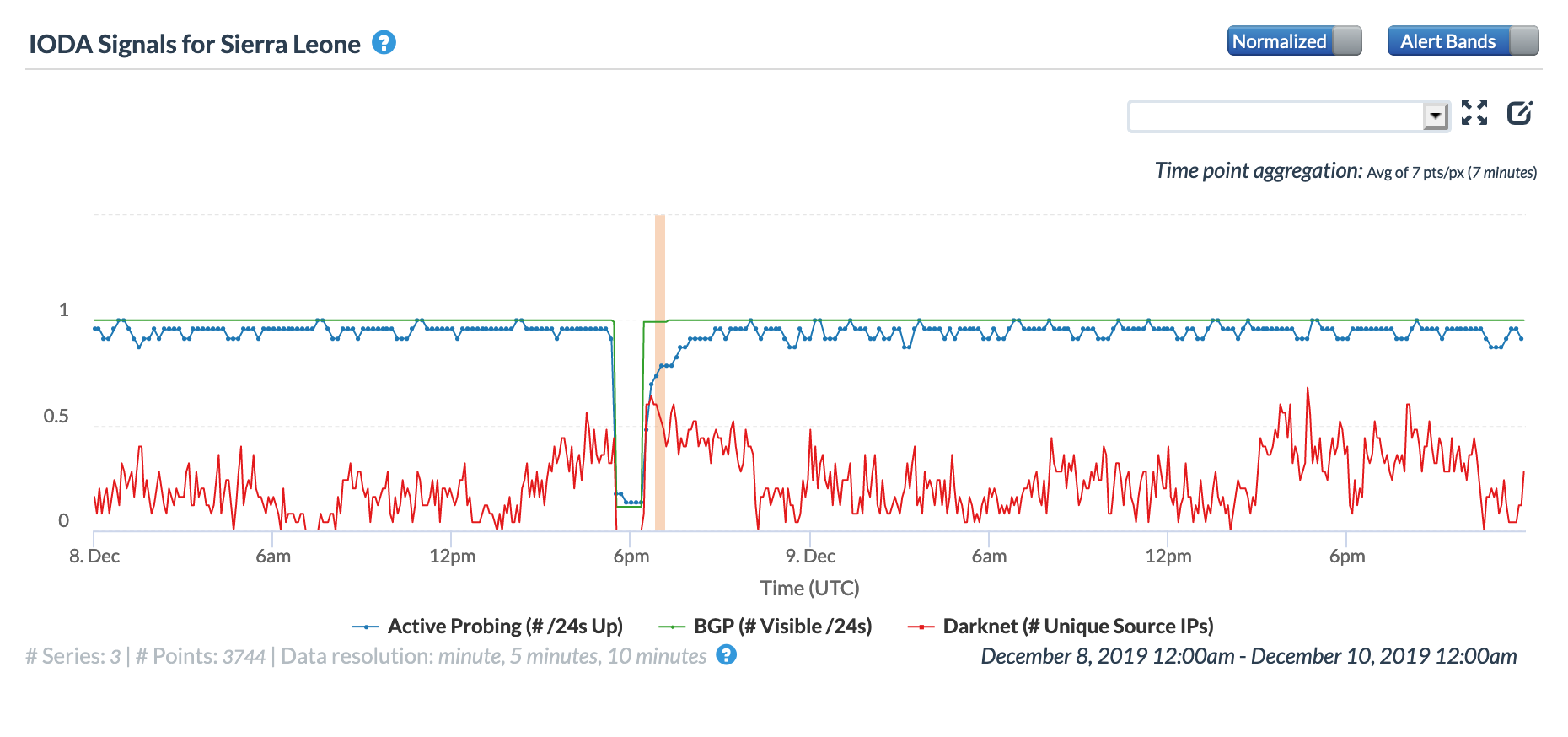

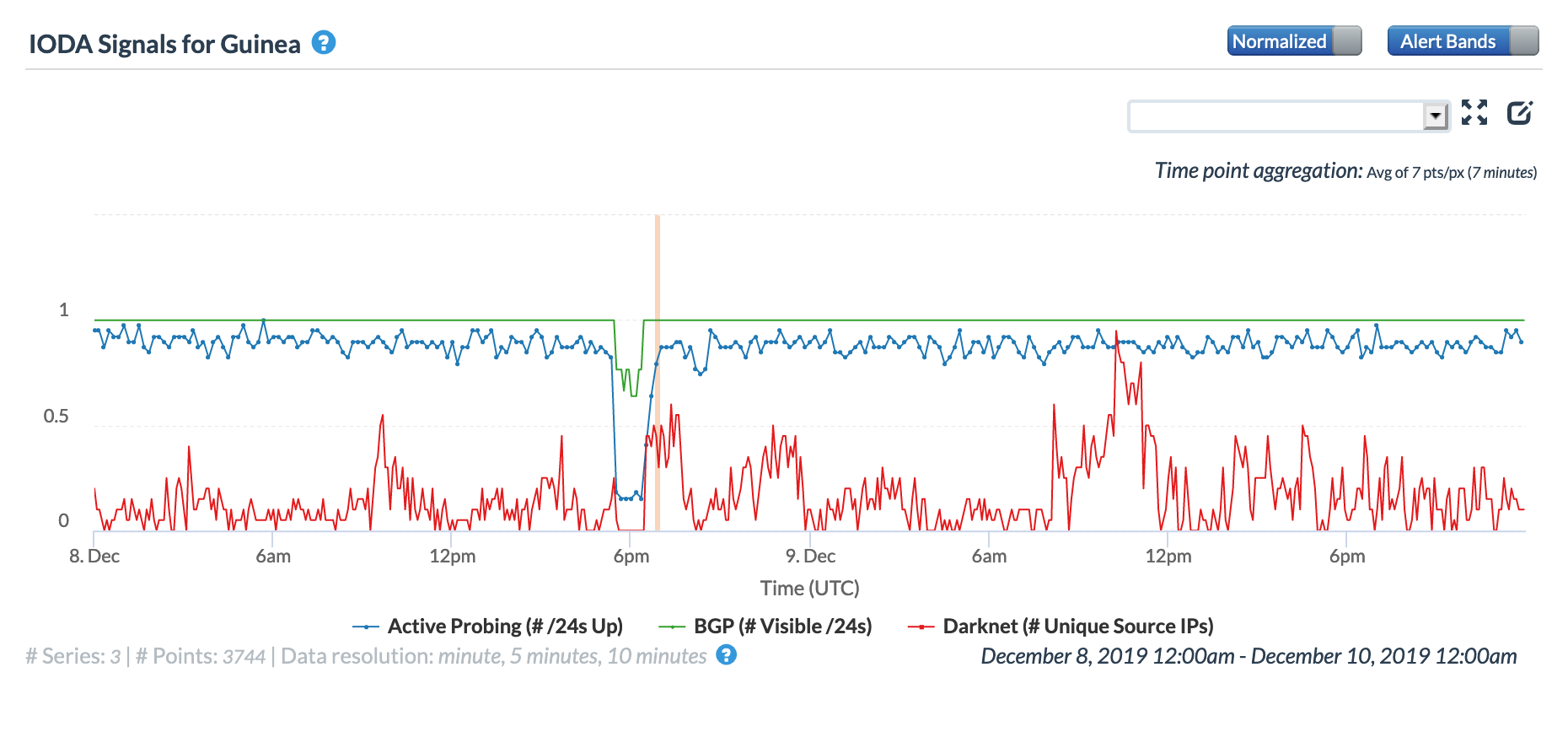

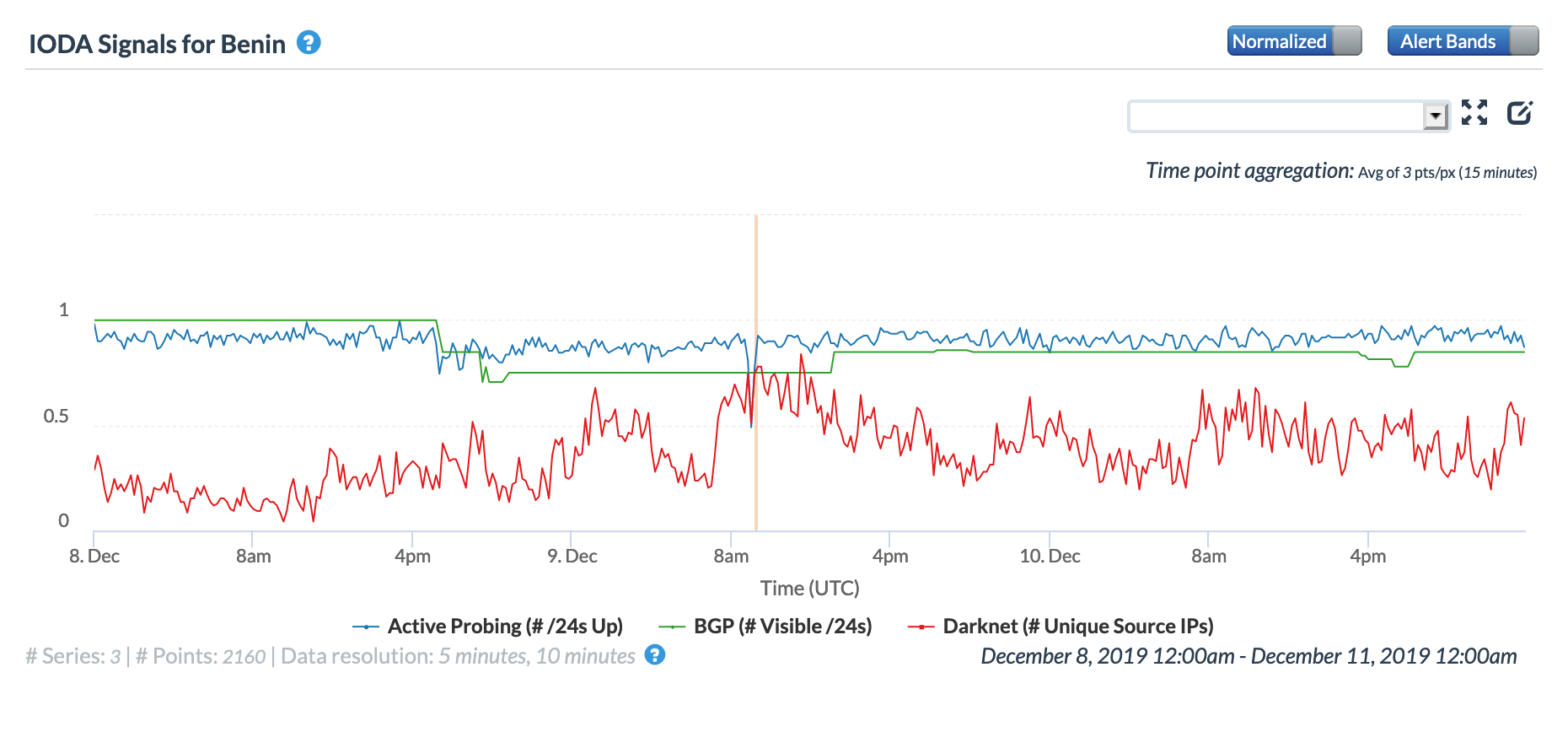

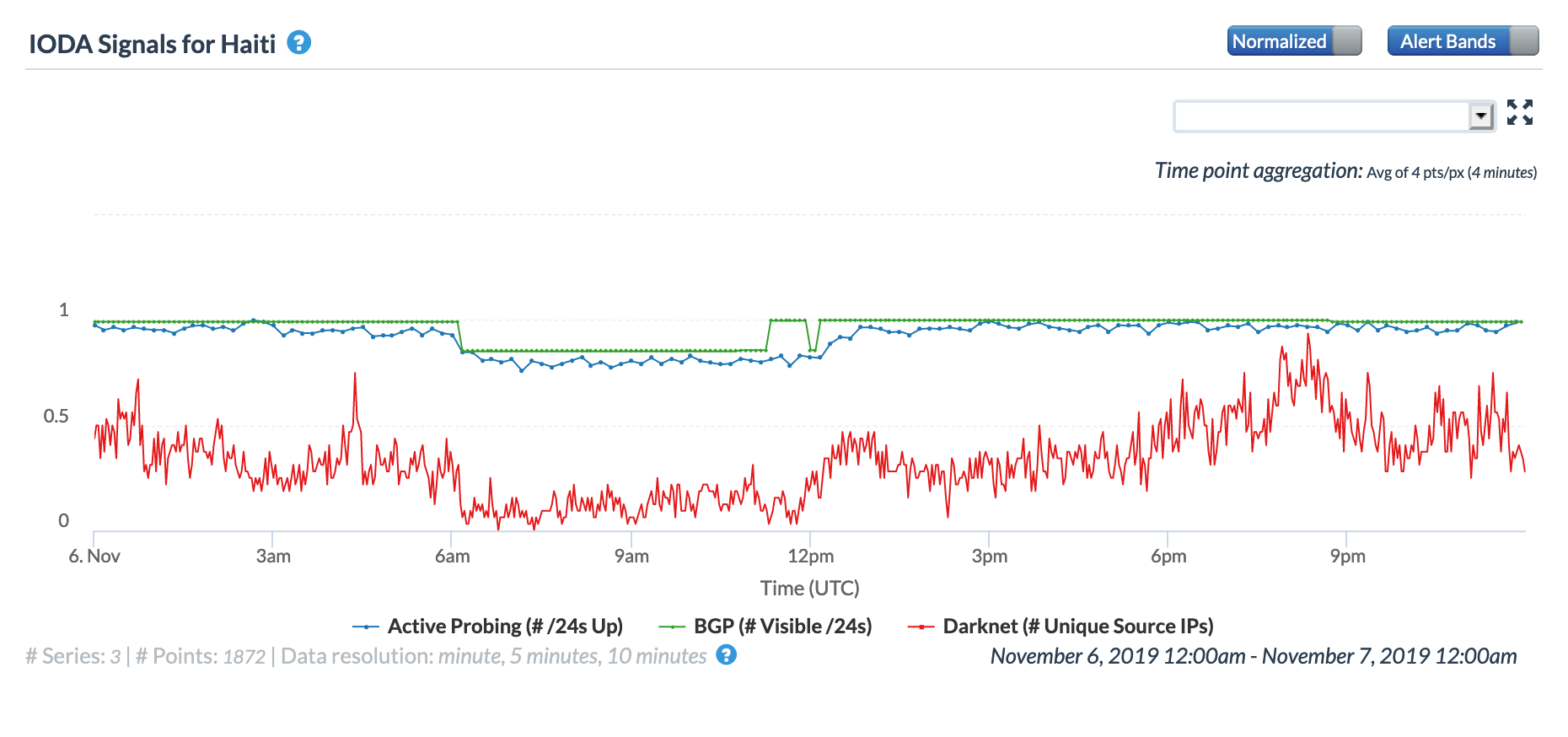

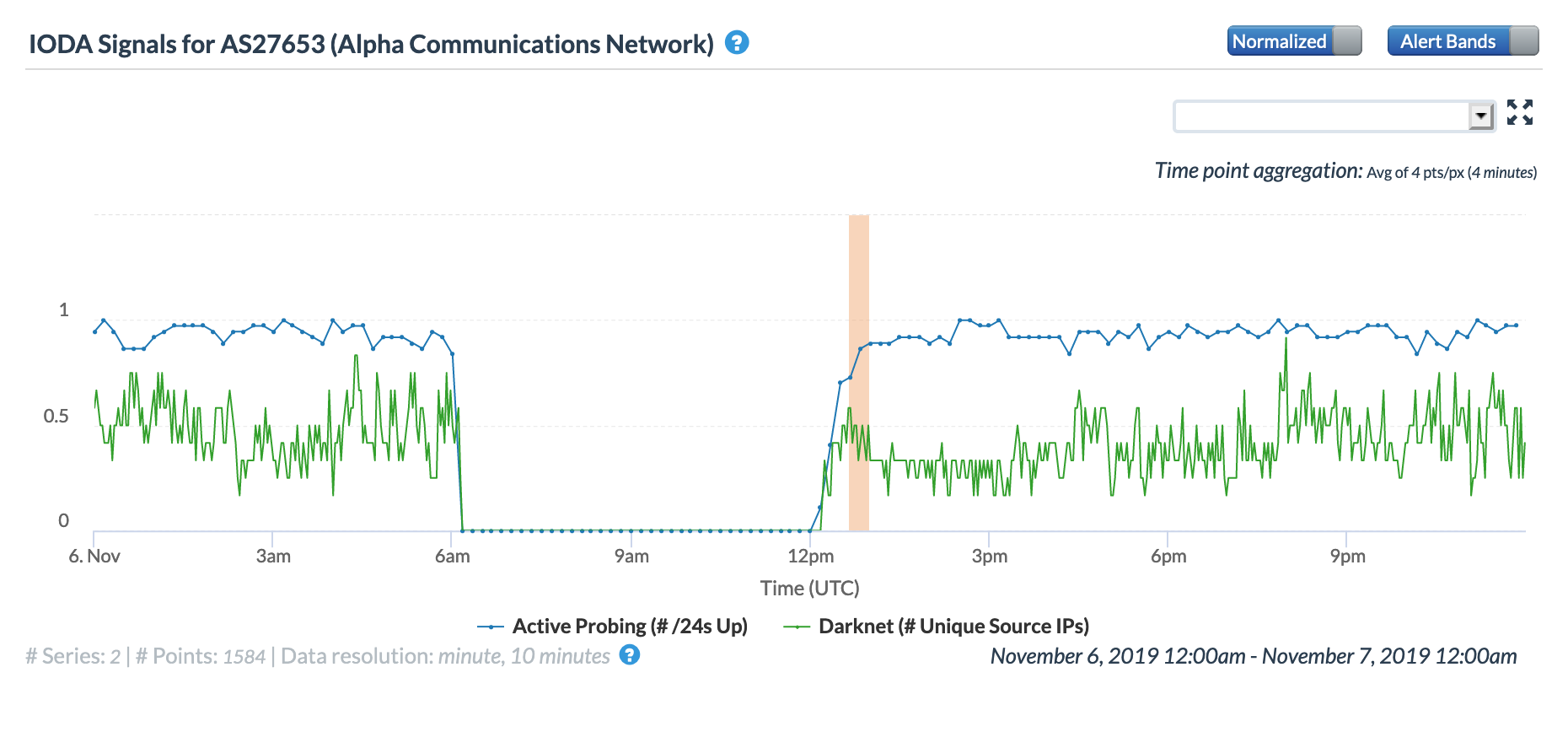

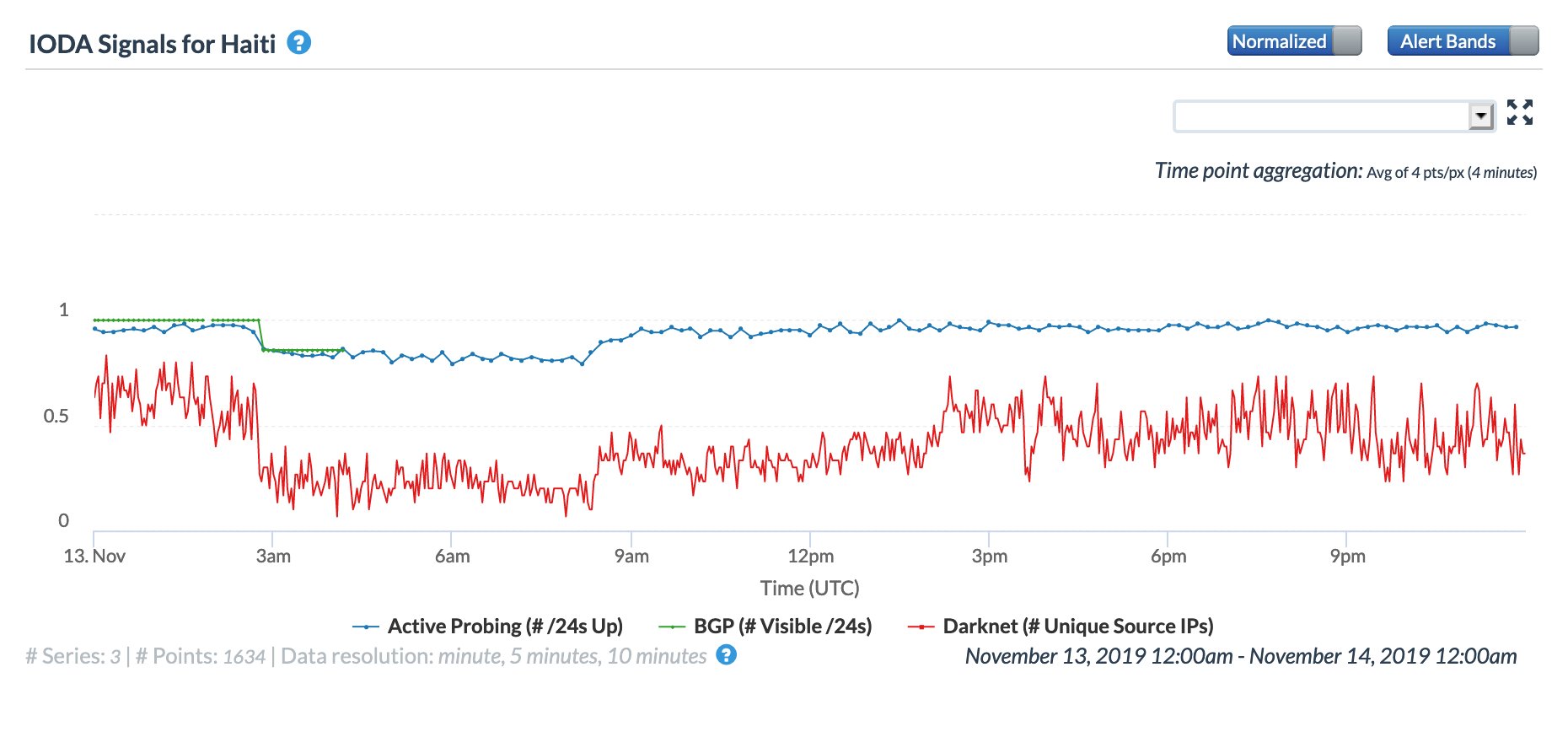

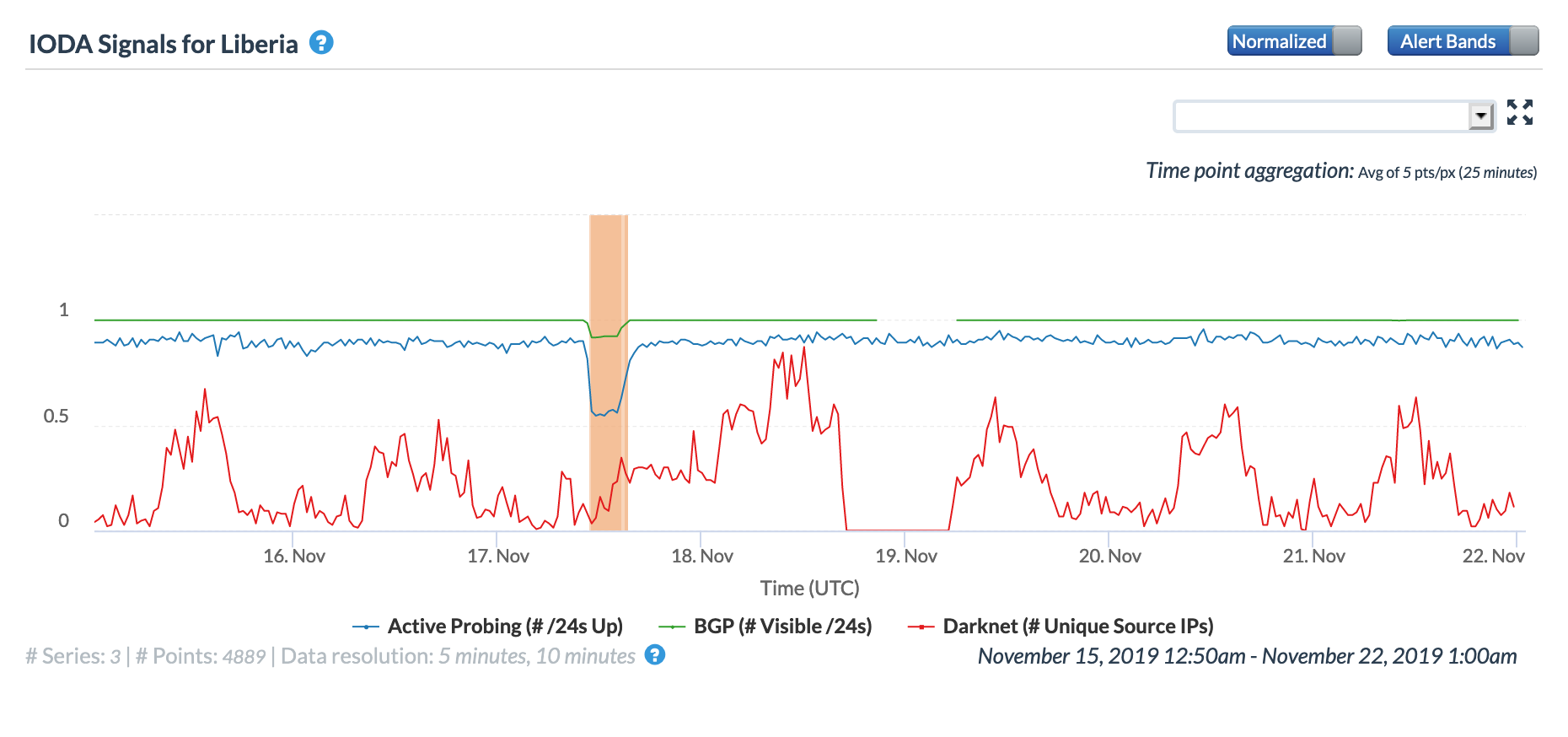

On December 8, concurrent Internet disruptions were observed in Oracle and CAIDA IODA graphs for Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia, and Benin from 1725 to 1825 GMT. In November, a similar event occurred, and we noted in that month’s post, “Because the Africa Coast to Europe (ACE) submarine cable lands in each of these countries, it was suspected that problems with the cable caused these observed disruptions.” That suspicion was confirmed by @acesubmarinec, but we received no response to outreach regarding this December disruption or a followup inquiry. However, given that all of the countries shown below are connected to the ACE cable, it is likely the culprit in this disruption as well.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Sierra Leone, December 8

CAIDA IODA graph for Sierra Leone, December 8

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Guinea, December 8

CAIDA IODA graph for Guinea, December 8

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Liberia, December 8

CAIDA IODA graph for Liberia, December 8

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Benin, December 8

CAIDA IODA graph for Benin, December 8

On December 10, Fing Internet Alert Tweeted about a significant Internet disruption experienced in multiple cities by customers of U.S. network provider Suddenlink.

This is #suddenlink situation today.#suddenlinkdown #suddenlinkhelp pic.twitter.com/YslH9SHvKb

— Fing Internet Alert (@outagedetect) December 10, 2019

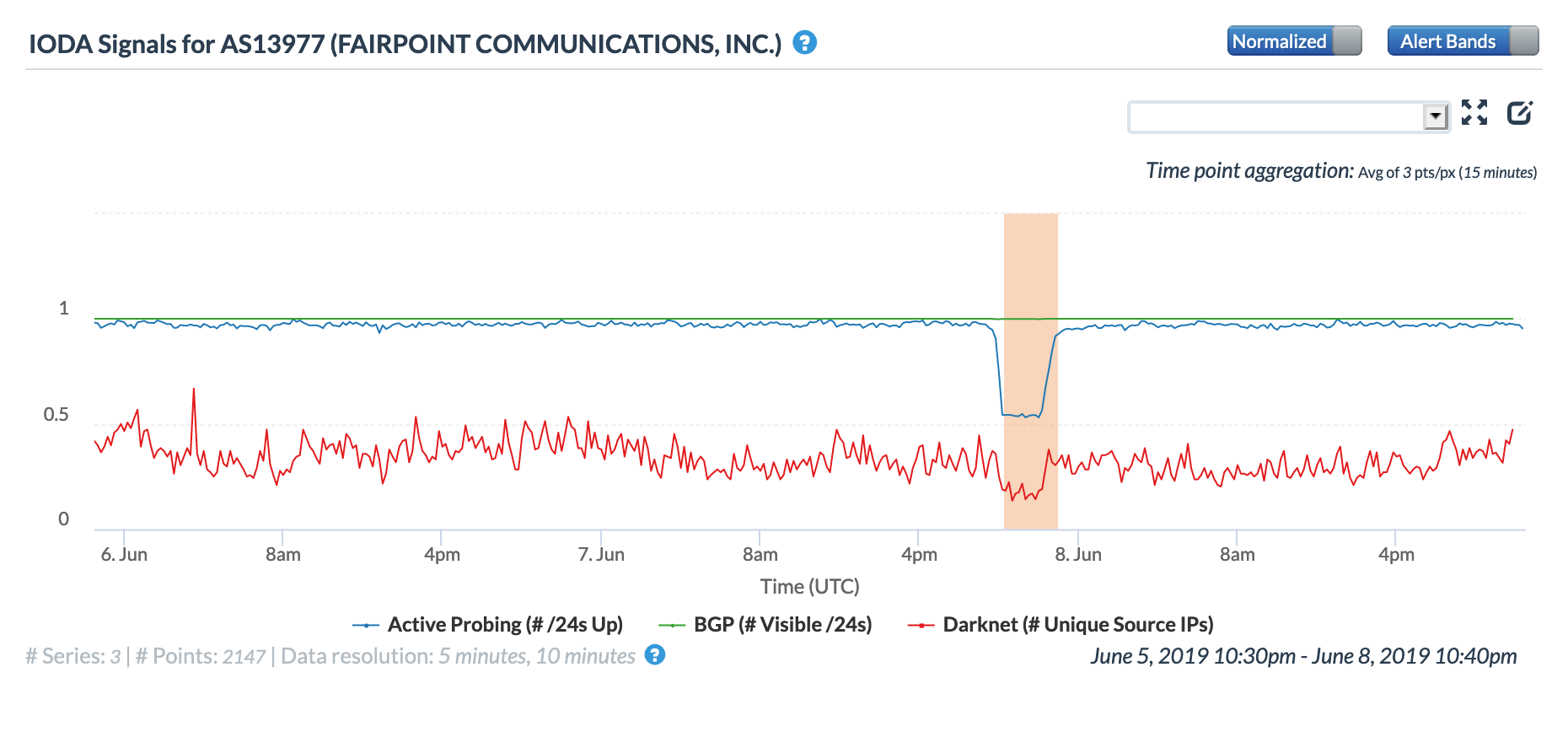

The figures below indicate that the issues started around 0630 GMT, with significant impact for approximately three hours. The Active Probing metric in the CAIDA IODA graph shows that the situation began to improve around 1000 GMT, but that the metric didn’t return to pre-disruption levels until around 1500 GMT. Although Suddenlink apologized to customers via Twitter, it did not respond to a request for more information about the cause of the disruption.

Making its second appearance in this month’s report, Malta also suffered an Internet disruption on December 12. However, this one was due to an outage on international connectivity for Go, the country’s leading telecommunications company. According to posts on the company’s Facebook page, the outage impacted both the company’s fixed and mobile Internet services.

The figures below show a country-level disruption starting around 1500 GMT across all metrics in both the Oracle and CAIDA IODA graphs, lasting until 1845 GMT. At a network level, the CAIDA IODA graph below shows all three metrics dropping to near zero during the period of disruption, while the Oracle graph appears to show that some traceroutes continued to successfully reach endpoints within the network. Malta is serviced by five international submarine cables, but Go did not specify which one suffered the outage. However, as Go is the owner of the GO-1 Mediterranean Cable System, and co-owner of the Italy-Malta cable, it is likely that the problem occurred on one of these.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Malta, December 12

CAIDA IODA graph for Malta, December 12

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Traffic Shifts graph for AS15735 (Go), December 12

CAIDA IODA graph for AS15735 (Go), December 12

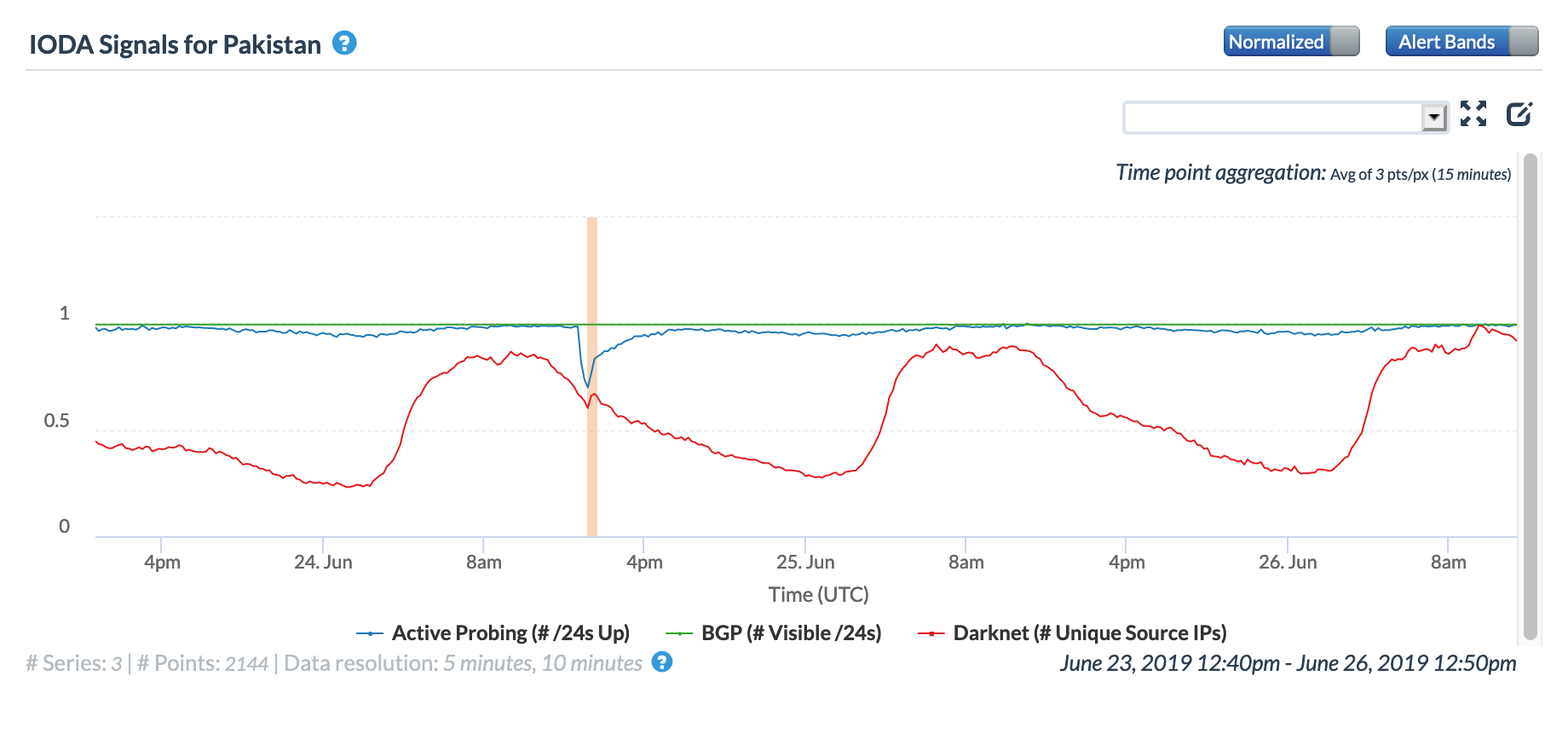

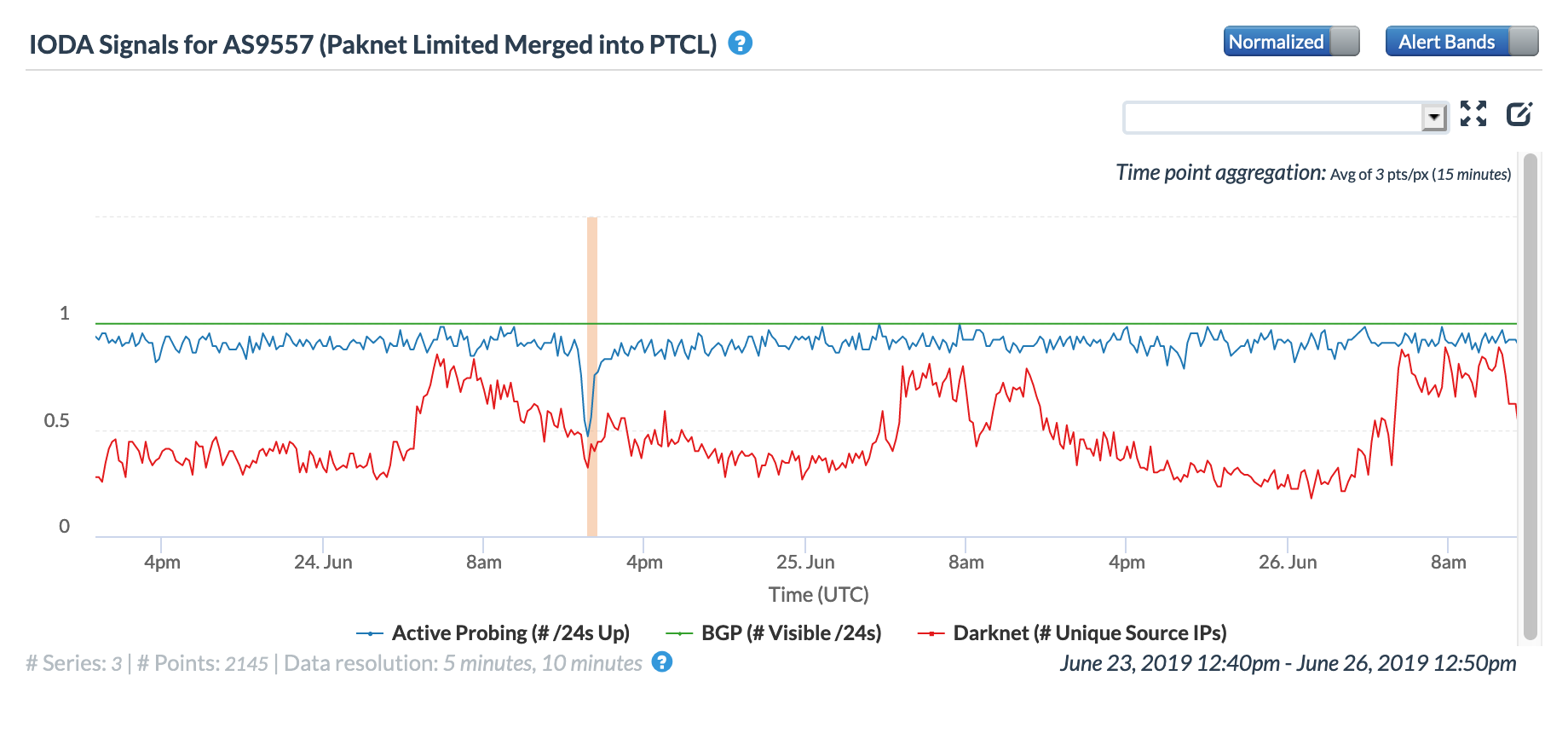

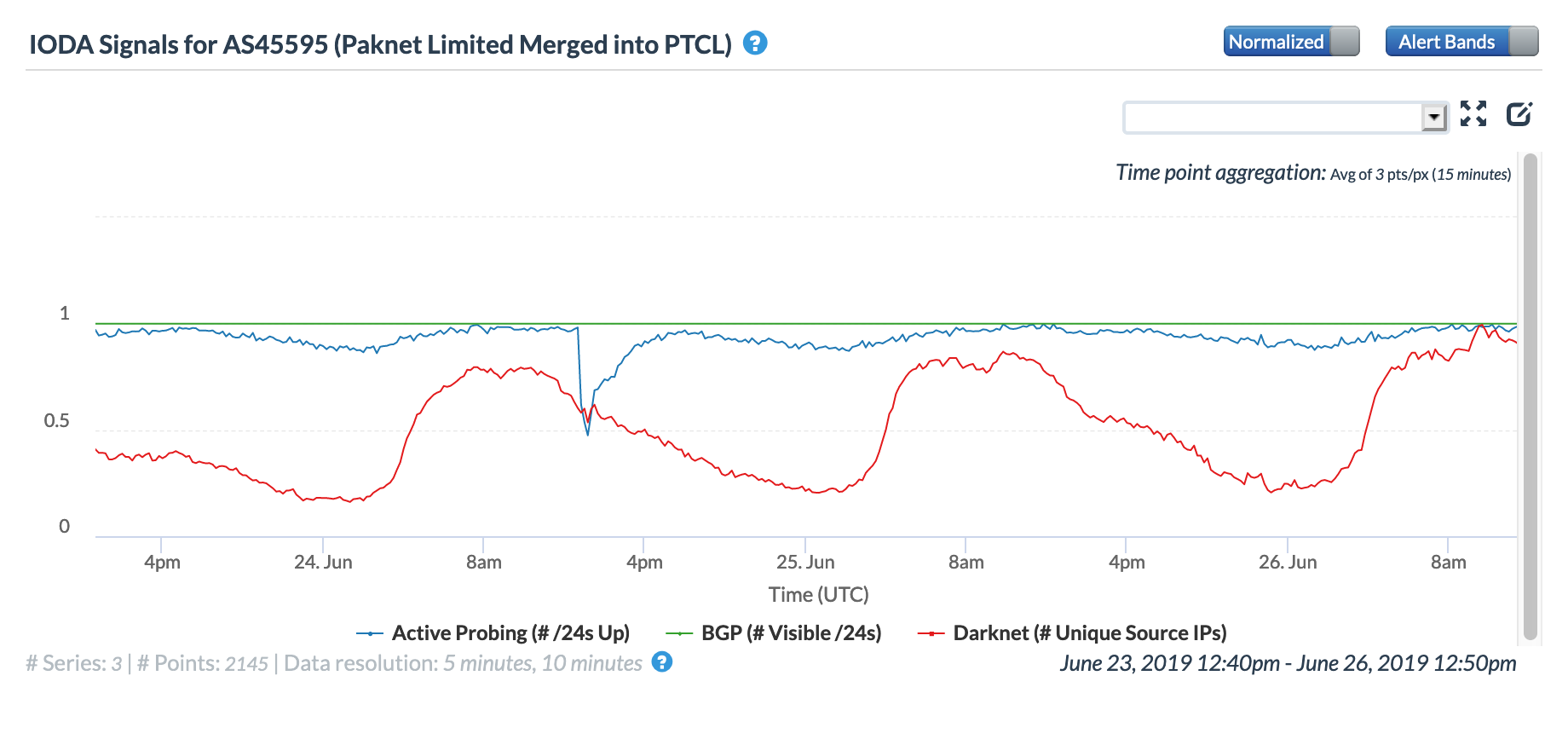

On December 15, PTCL, Pakistan’s national telecommunications company, alerted customers of potential service degradation due to a fault in the Asia Africa Europe-1 (AAE-1) submarine cable.

Internet services are impacted & you may face some service degradation due to technical fault in the International Submarine Cable AAE-1 at Doha. PTCL in conjunction with the International Submarine Consortium, is working to fully restore internet services across the country. 1/2

— PTCL (@PTCLOfficial) December 15, 2019

The figures below show the impact of the cable issue on Oracle Internet Intelligence traceroutes to endpoints in two PTCL autonomous systems. In both instances, the number of successful traceroutes did not decline, but combined latency increased by 50-75ms. Based on the timing of a followup Tweet posted by @PTCLofficial, service was restored after approximately five-and-a-half hours.

After a government-directed nationwide Internet disruption in November, initial reactions to connectivity issues observed in Iran on December 19 reflected concerns that another such event was taking place. However, Sadjad Bonabi (@sadjadb), a member of the Board of Directors of Iranian infrastructure provider TIC, posted a series of Tweets [1, 2, 3] over several hours explaining that the disruption was due to fiber breaks near Bucharest and Munich, and that service providers such as Google were also impacted. An Iranian news site also noted that the disruption was “related to fiber optic lines from Europe.” A subsequent update from NetBlocks indicated that connectivity to Google services in Turkey and Bulgaria had been impacted at the same time.

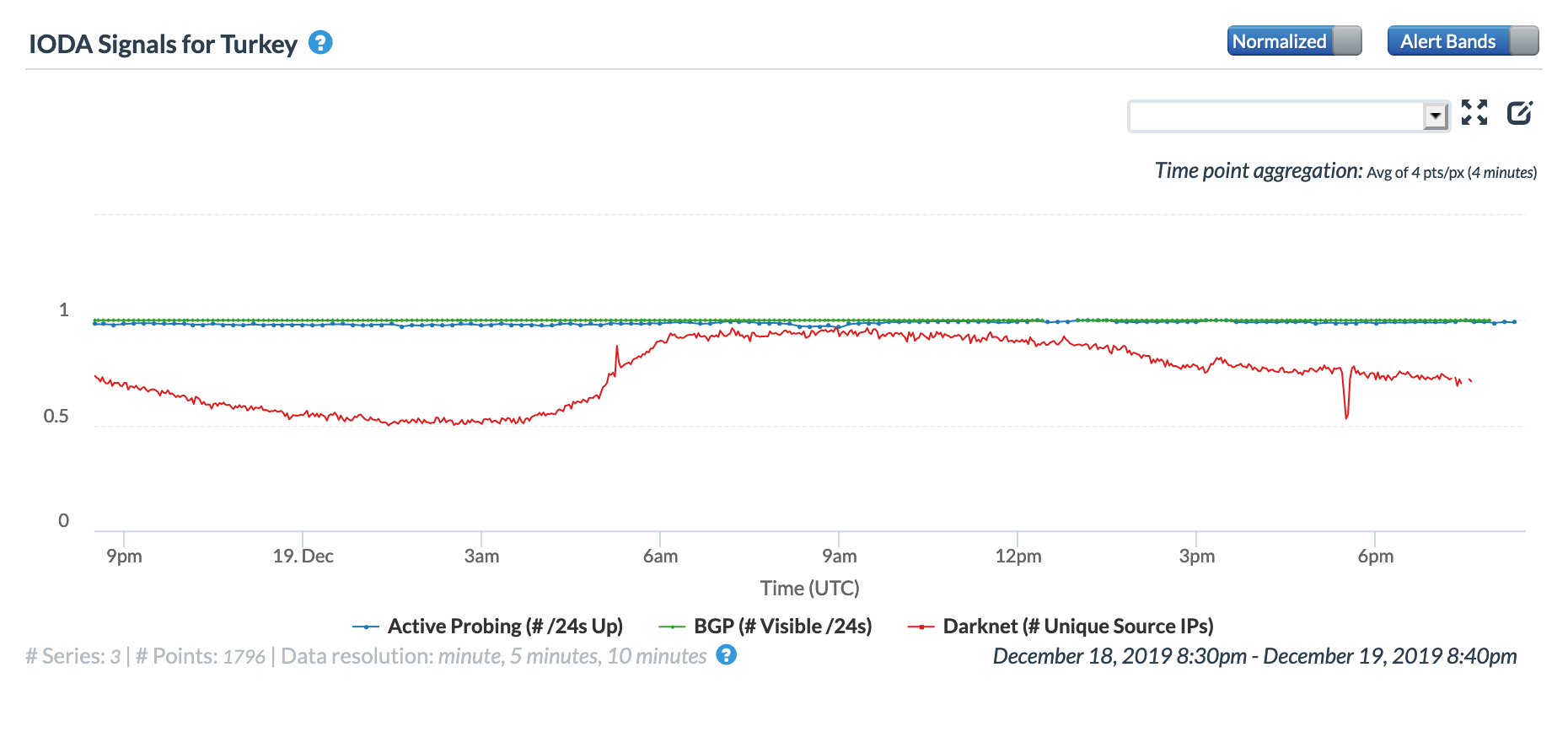

The figures below highlight the impact of this network issue at a country level in Iran, Turkey, and Bulgaria. Both the Oracle and CAIDA IODA graphs show that the most significant impact was observed in Iran, with changes to the measured metrics for Turkey and Bulgaria much more nominal in the Oracle graphs, and nearly imperceptible in the CAIDA IODA graphs.

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Iran, December 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Iran, December 19

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Turkey, December 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Turkey, December 19

Oracle Internet Intelligence Map Country Statistics graph for Bulgaria, December 19

CAIDA IODA graph for Bulgaria, December 19

As was noted by Sadjad Bonabi and NetBlocks, the network disruption impacted Google services in the affected countries, and Google’s Cloud Status Dashboard reported an “issue with multiple simultaneous fiber cuts affecting traffic routed through Google’s network in Bulgaria.” The figures below illustrate how the fiber cuts impacted traffic to Google’s YouTube, Maps, and GMail services (left-to-right) from users in Iran, Turkey, and Bulgaria (top-to-bottom). A brief but obvious dip in traffic is evident in each graph at the time the disruption occurred.

(click images to enlarge)

A day later, mid-Atlantic region customers of U.S. Internet provider Comcast experienced a brief Internet disruption. The screenshot below from Fing Internet Alerts shows that the disruption impacted subscribers in Maryland, Virginia, the District of Columbia, Delaware, and West Virginia.

The Fing Internet Alerts graphs below show that the disruption began just before midnight local time (0500 GMT) on December 20, and lasted for approximately an hour. This timing is corroborated by the CAIDA IODA graph below, but given the localized impact of the disruption, the impact to the measured metrics is minimal.

A thread on the Outages mailing list explained that the disruption happened because “There was a maintenance in one part of a regional network, but there was an optical line failure in another part of that same network that happened during the maintenance.”

Fing Internet Alerts graph for AS7922 (Comcast) in Washington DC, December 20

Fing Internet Alerts graph for AS7922 (Comcast) in Delaware, December 20

Fing Internet Alerts graph for AS7922 (Comcast) in Maryland, December 20

Fing Internet Alerts graph for AS7922 (Comcast) in Virginia, December 20

Fing Internet Alerts graph for AS7922 (Comcast) in West Virginia, December 20

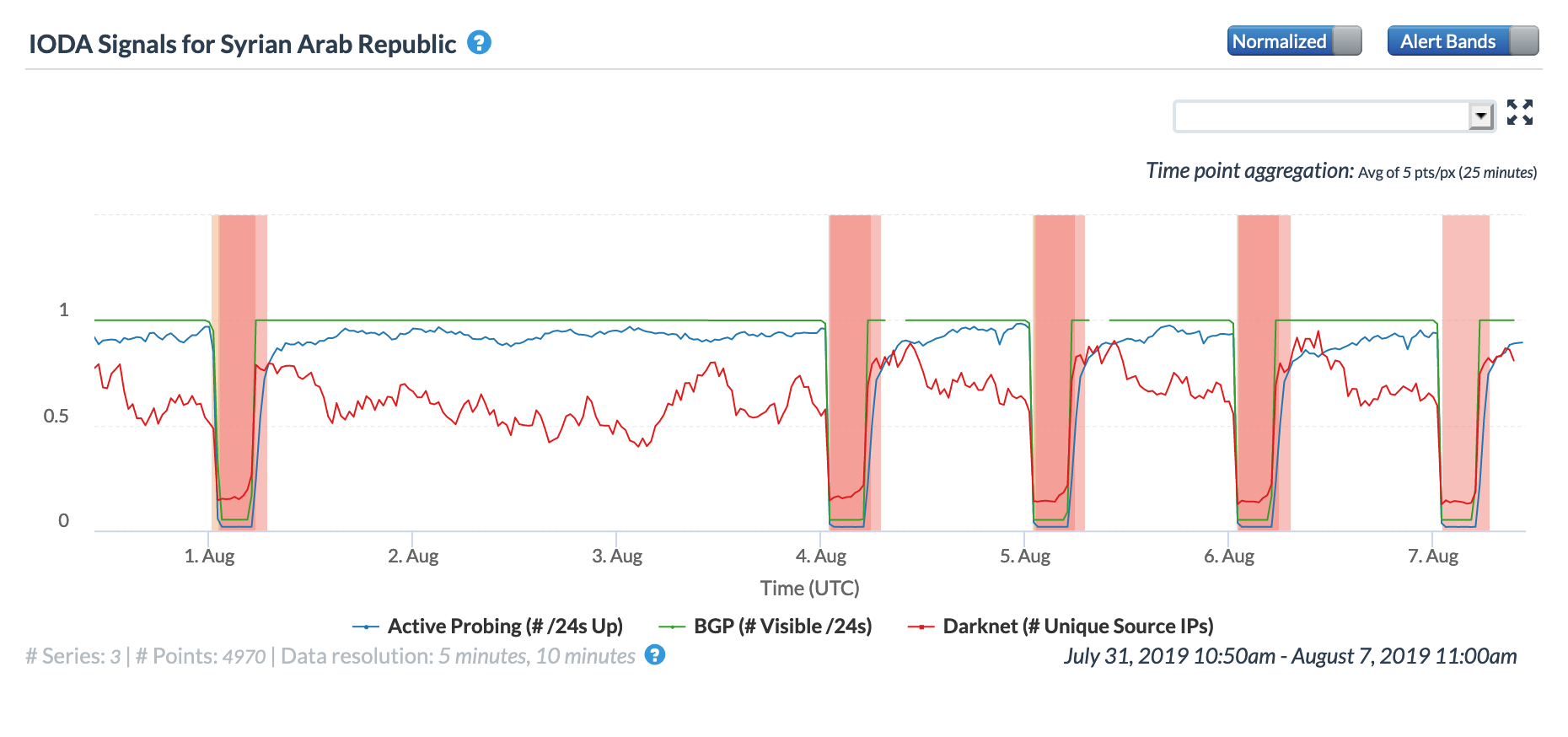

Government Directed

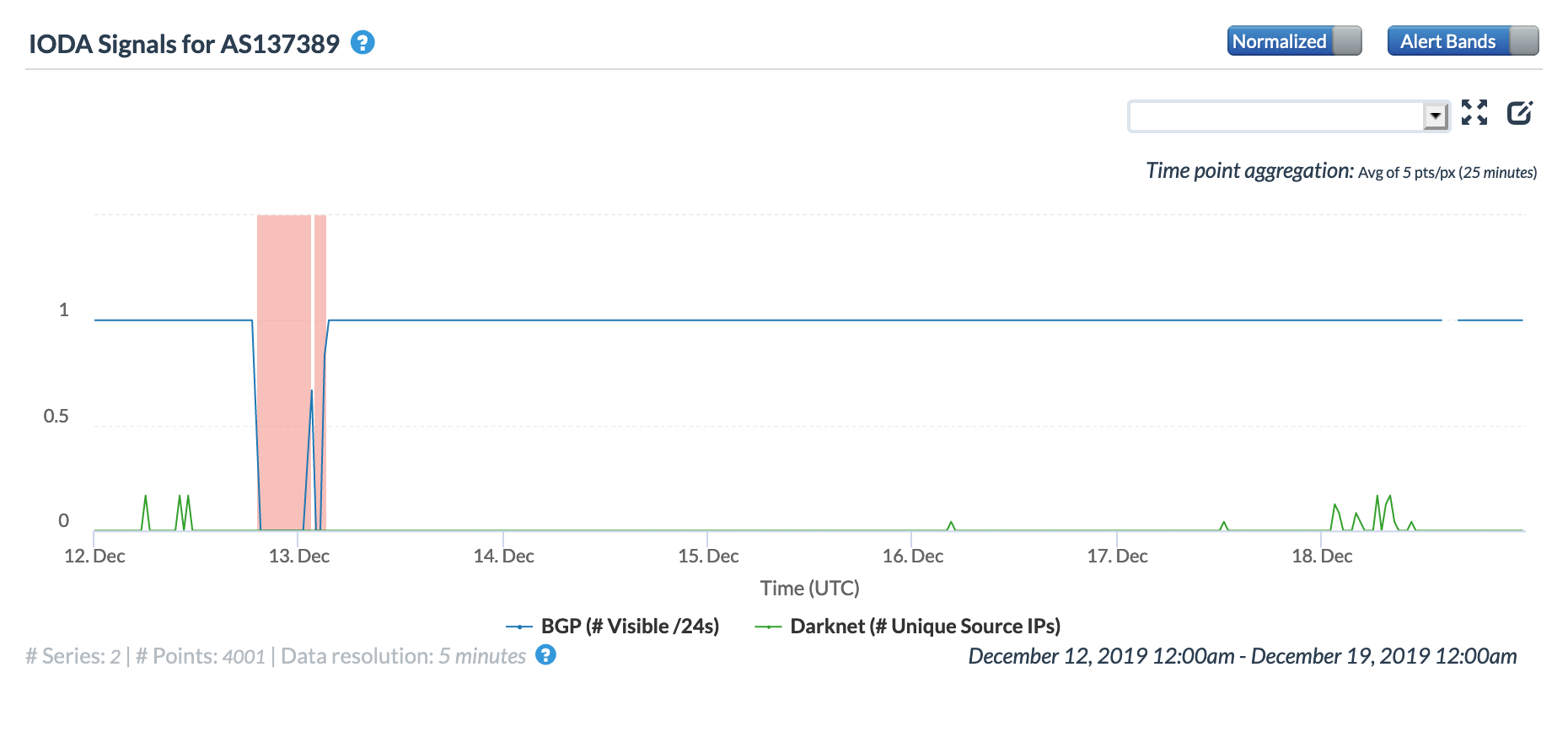

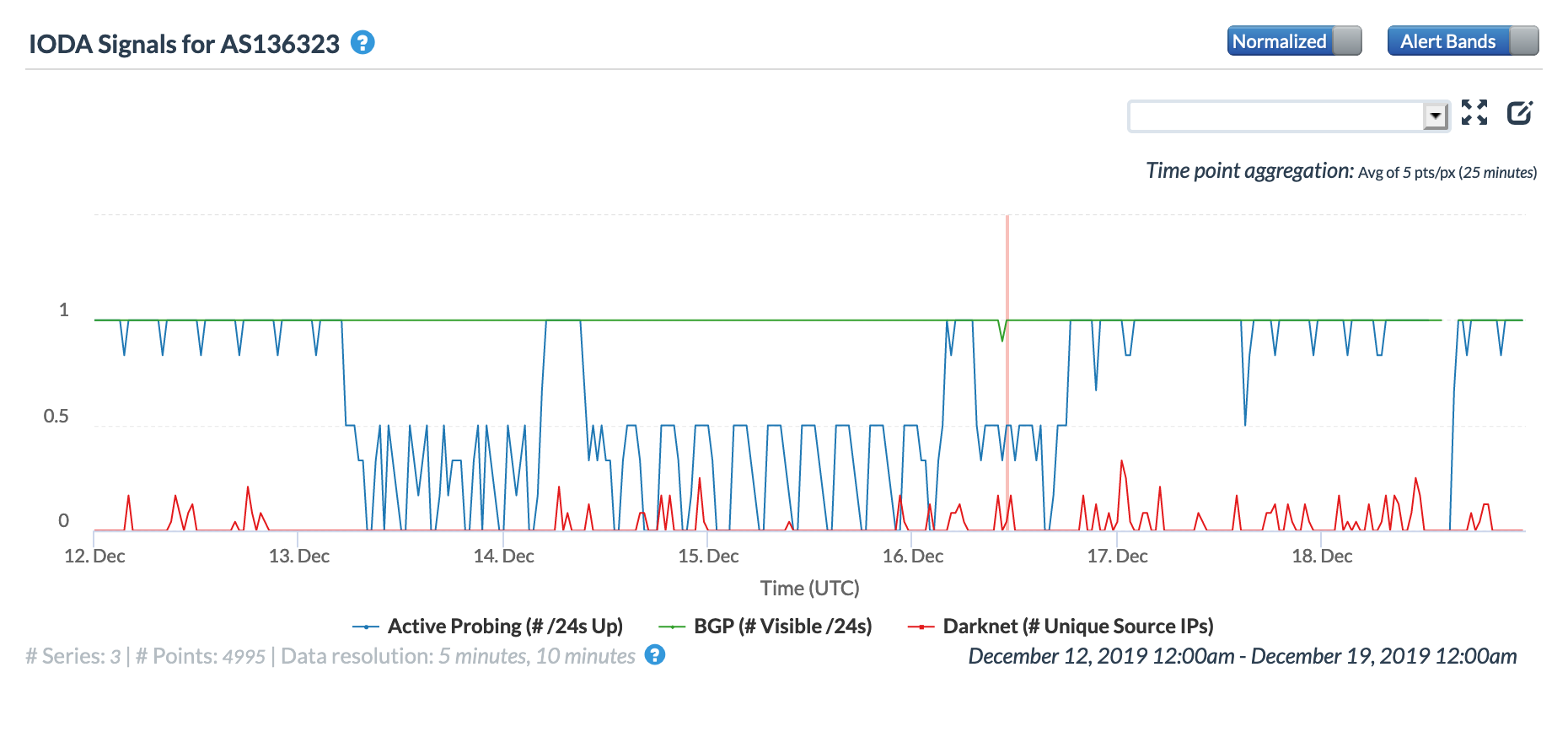

No stranger to government directed Internet shutdowns, India moved to shut down Internet services in the northern states of Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya on December 12. The shutdown was ordered in response to protests stemming from the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Bill. According to a Tweet and subsequent report posted by NetBlocks, the actions impacted both fixed and mobile network providers. Within the Tweet and report, NetBlocks showed connectivity levels it measured for the autonomous systems of seven local network providers.

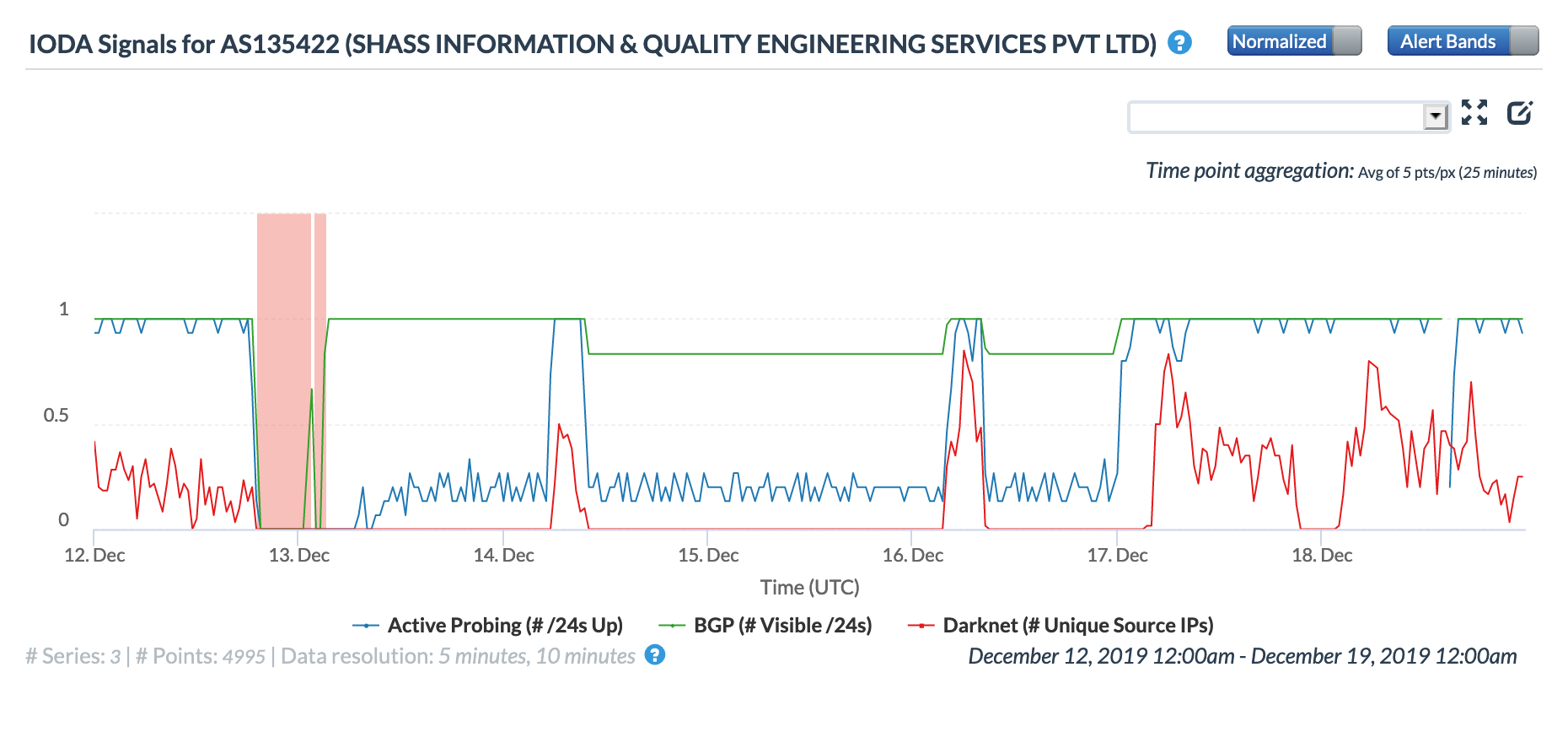

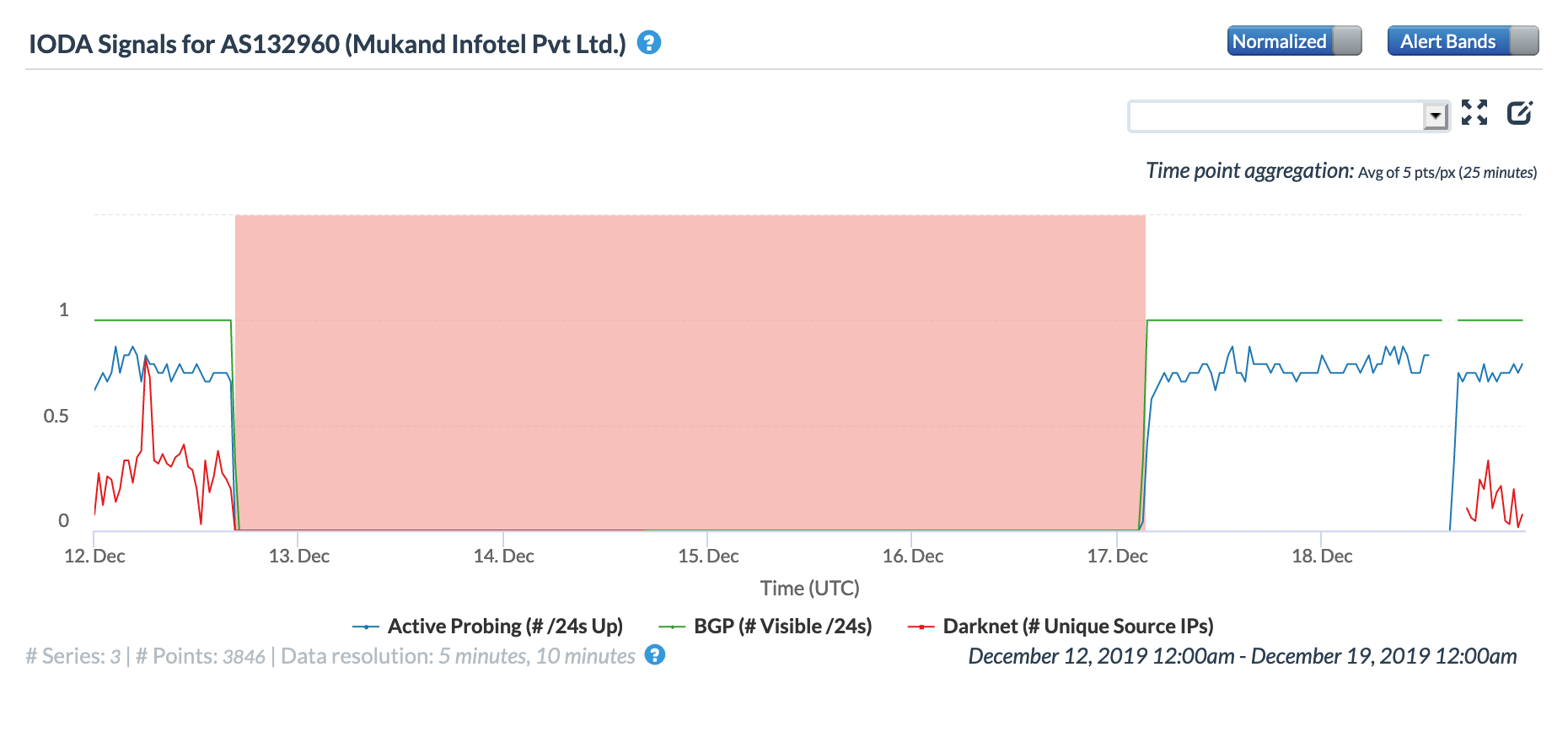

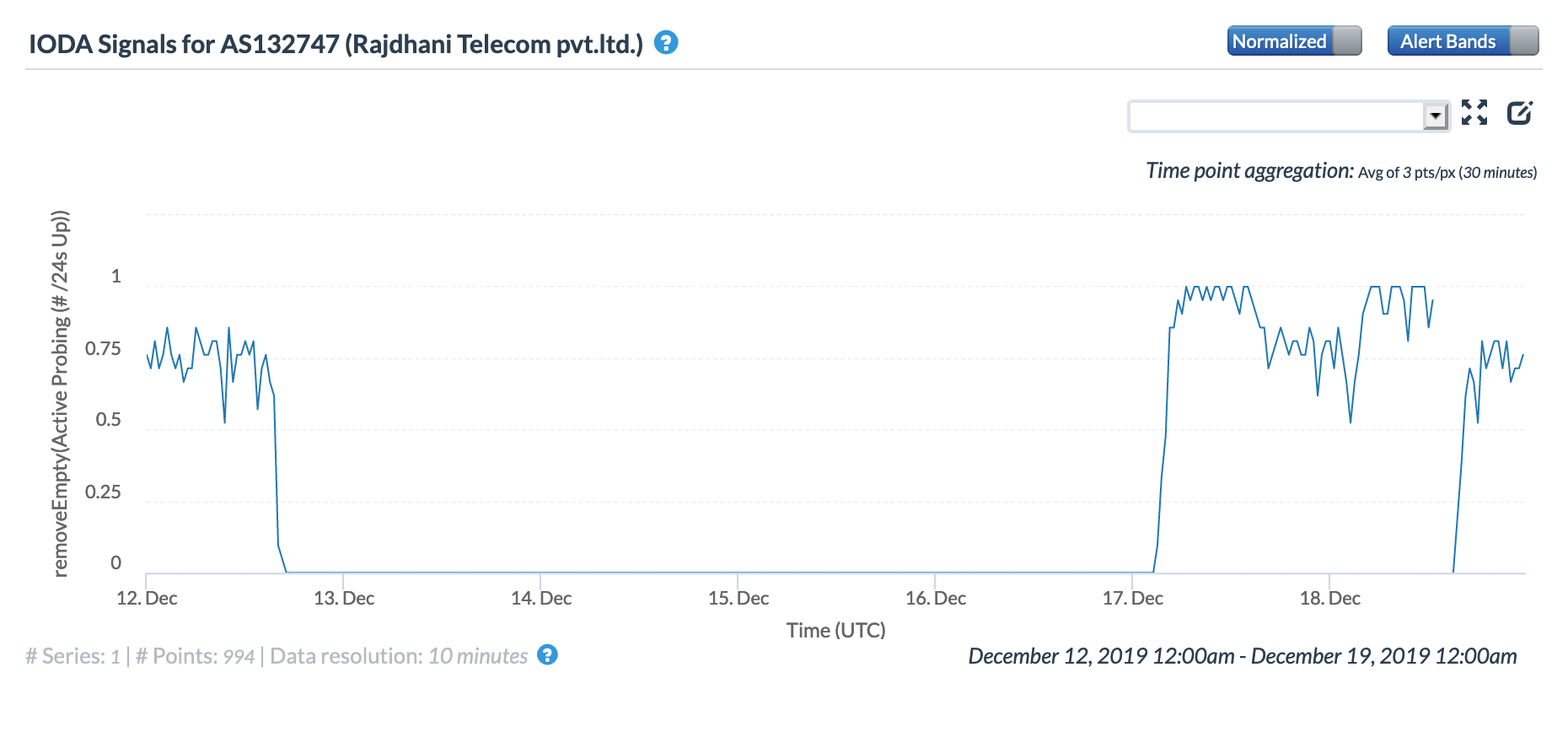

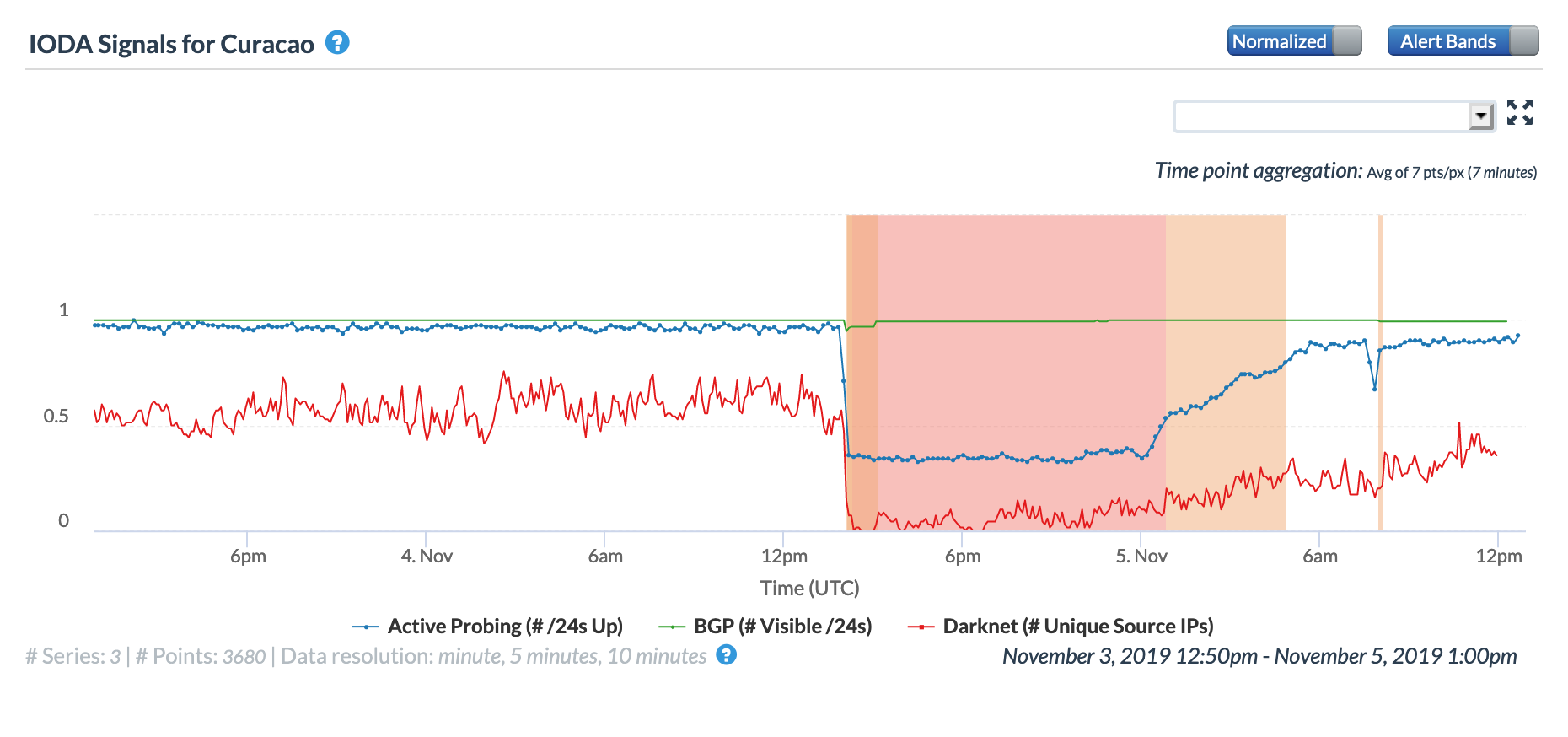

The figures below show how connectivity to these providers was seen by CAIDA IODA measurements during the multi-day disruption. While the start of the disruption at ~1600 GMT on December 12 is generally evident across the graphs, there are noticeable differences across them as well. These differences may be due to the types of network each autonomous system is associated with, as mobile networks are significantly harder to measure into from external vantage points. Several see restoration and disruption events that align with those seen in NetBlocks’ report, while others appear to show a complete loss of connectivity for over four days.

CAIDA IODA graph for AS138257, December 12-18

CAIDA IODA graph for AS137389, December 12-18

CAIDA IODA graph for AS136323, December 12-18

CAIDA IODA graph for AS135422, December 12-18

CAIDA IODA graph for AS132960, December 12-18

CAIDA IODA graph for AS132747, December 12-18

CAIDA IODA graph for AS131463, December 12-18

A court order published on December 19 ordering the restoration of services highlighted the detrimental affect that the loss of Internet connectivity has had on everyday life:

- “It has been impressed on the Court that even electricity supply has been snapped to certain houses of the lawyers because pre-paid meters have been installed, which can only be charged through the Internet.”

- “Under the circumstances, none of the business establishments is able to transact business causing serious disruption in normal living of the citizens in the area.”

- “To say the least, with the advancement of science and technology, mobile Internet services now plays a major role in the daily walks of life, so much so, shut-down of the mobile Internet service virtually amounts to bringing life to a grinding halt.”

Additional protests over the Citizenship Amendment Bill caused the Indian government to order the shutdown of mobile Internet connectivity in New Delhi, as well as the suspension of Internet services in Aligarh, Meerut, Malda, Murshidabad, Howrah, and parts of West Bengal during this timeframe as well. On December 26, similar steps were taken in Uttar Pradesh.

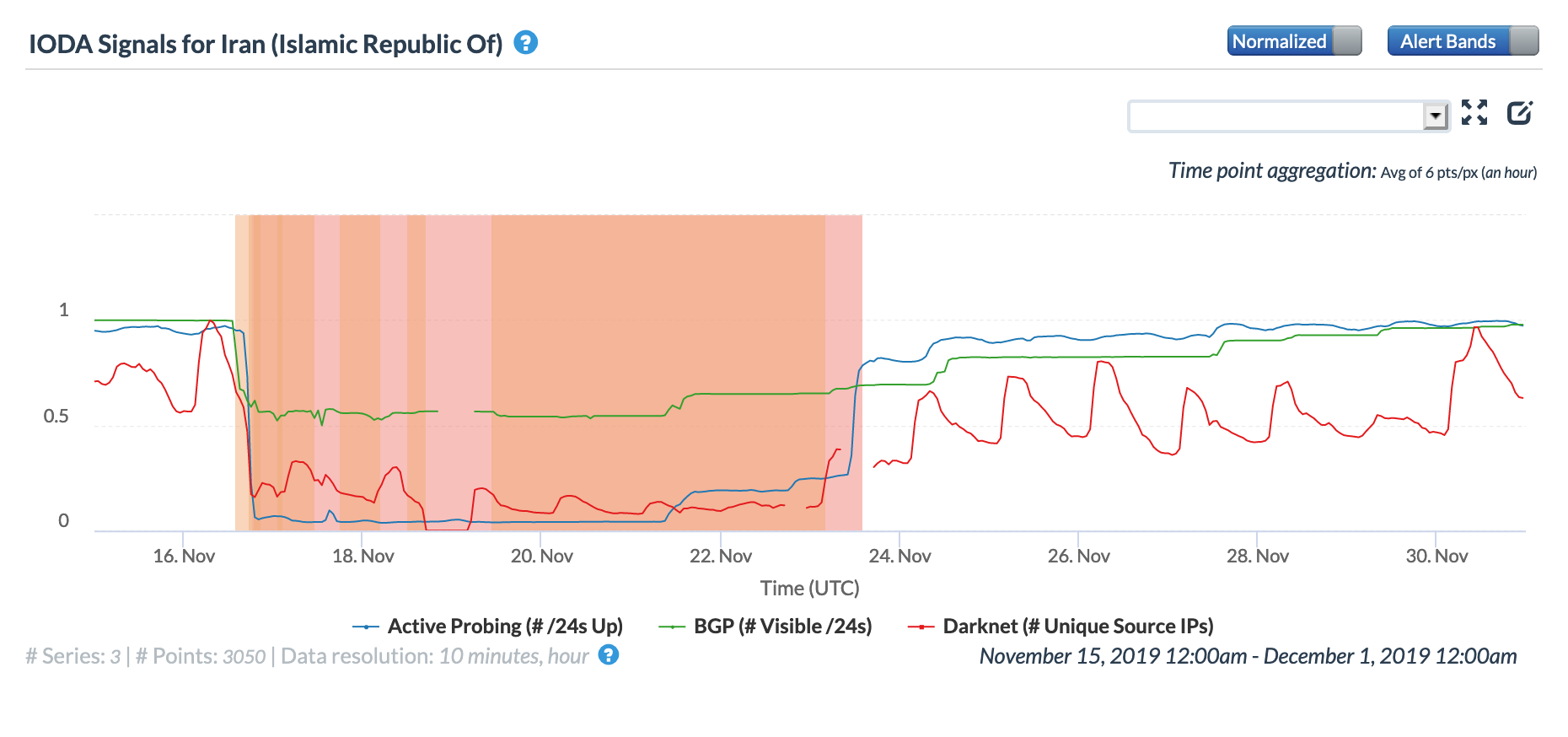

As reviewed in the November 2019 Internet Disruption Report, Iran suffered a week-long government directed Internet shutdown in response to protests over gasoline prices. On December 25, the Iranian government ordered restrictions on mobile Internet access in several provinces ahead of protests and ceremonies to remember those killed in the prior month’s protests.

A NetBlocks Tweet about the ordered mobile shutdown looked at the impact on connectivity for AS57218 (Rightel), one of three mobile providers in Iran.

Update: Mobile internet connectivity has fallen further in #Iran amid reports of security reinforcement; real-time network data show connectivity at 5% of ordinary levels on specified networks after four distinct cuts; incident ongoing

— NetBlocks.org (@netblocks) December 26, 2019#Internet4Iran

https://t.co/BNTPP9wEyt pic.twitter.com/Wh2uy5xIxp

The figure below shows the impact of the order shutdown on Rightel as observed by CAIDA IODA’s measurements. The changes to the BGP and Active Probing metrics show that connectivity was lost in several stages, with Active Probing reaching its lowest level just before 1200 GMT on December 26. Connectivity was apparently restored around 0500 GMT on December 28 as the Active Probing and BGP metrics rose rapidly, returning to pre-disruption levels.

Interestingly, CAIDA IODA graphs for the country’s other two national mobile providers (Iran Cell and MCI) did not show similar disruptions to connectivity.

Russian Internet Disconnection Test

On December 23, a post to tech news aggregator Slashdot claimed “Russia has temporarily shut off many of its citizens’ access to the global internet today in a test of its controversial RuNet program, according to an internal government document.” That same day, ZDNet declared “Russia successfully disconnected from the internet”, noting “RuNet disconnection tests were successful, according to the Russian government.” The BBC picked up the story two days later.

According to the BBC article, “Details of what the test involved were vague but, according to the Ministry of Communications, ordinary users did not notice any changes.” The ZDNet article noted “The tests were carried out over multiple days, starting last week, and involved Russian government agencies, local internet service providers, and local Russian internet companies. … Internet traffic was re-routed internally, effectively making Russia’s RuNet the world’s largest intranet.” With this explanation, these tests would presumably have been visible in some fashion from outside the country.

However, that did not seem to be the case. Graphs from Oracle’s Internet Intelligence Map and CAIDA IODA did not show any noticeable changes to the measured metrics, and routing statistics from RIPENCC confirmed BGP’s stability over the period in question. Google Transparency Report traffic graphs for Web search, YouTube, GMail, and Blogger services did not show any deviations from the expected diurnal patterns and contacts at two leading CDN providers also reported no noticeable changes to traffic patterns from Russia during the time the test reportedly took place. Additionally, traffic graphs from IXPs within Russia, as well as DECIX, did not show any evidence of changes in traffic volume that would be expected if an Internet shutdown had occurred.

With a lack of evidence across major Internet platforms and measurement tools, we might ask whether the disconnection test actually occurred, as was reported, and if so, what was tested. The translation of a Russian-language article may provide some insight. According to the article, the disconnection may have been an “exercise” conducted in a test environment, rather than on Russia’s production Internet. The article also notes that exercises held on December 16 & 17 involved the SS7 and Diameter signaling protocols – these are used in the back-end of telecom networks, and are not related specifically to the Internet. It isn’t clear whether the tests that reportedly took place on/around December 23 also only focused on telecoms, rather than native Internet, infrastructure. Several additional Russian-language articles (1, 2) also questioned whether the tests had actually taken place, as well as the reported results of the tests.

Additional Observations

Recognizing that its reliance on a lone submarine cable for international Internet access represents a single point of failure, the government of Tonga is reportedly taking steps to implement backup satellite-based Internet connectivity. The goal is to avoid a repeat of the nationwide Internet outage that occurred in January 2019.

A “digital decree” passed by Spain’s government in late November reportedly gives it the power to shut down Internet connectivity in specified areas without prior judicial order. The relevant text is an adaptation of Section 4 of Article 4 of the current General Telecommunications Law:

“The Government, on an exceptional and transitory basis, may agree on the assumption by the General State Administration of direct management or the intervention of electronic communications networks and services in certain exceptional cases that may affect public order, public safety and national security This exceptional power may affect any infrastructure, associated resource or element or level of the network or service that is necessary to preserve or restore public order, public safety and national security. “ (via Google Translate)

As expected, concerns were raised about the constitutionality of the new rules, and about potential human rights violations associated with Internet shutdowns enabled by the decree.

In December, the Internet shutdown in Rakhine, Myanmar entered its seventh month and the shutdown in the Kashmir region of India entered its fifth month. These shutdowns have had a significant impact on the local economies, affecting small local businesses, as well as limiting the delivery of e-government services. At the end of 2019, it was observed by CNN and Quartz that Internet shutdowns have effectively become the ‘new normal’ and are/will be an increasingly popular mechanism for government repression.

Conclusion

I launched the Internet Disruption Report in May 2019 as a continuation of work that I had done as founding editor of Akamai’s State of the Internet/Connectivity Report, as well as the monthly “Last Month In Internet Intelligence” blog posts I published as a member of the Oracle Internet Intelligence team. Response has been very positive, and I am extremely grateful to those organizations that not only monitor and measure the Internet, but also make their findings and analysis publicly available. I also applaud those network providers that make effective use of social media channels to provide notice of, and status updates regarding, both planned and unanticipated disruptions, as well as those providers that respond to requests for more information about such disruptions. (Hint, hint…)

Given the growing trend towards government directed Internet shutdowns, and the otherwise unavoidable Internet disruptions caused by power outages, cable and fiber cuts, routing issues, and DDoS attacks, I am likely (for better or worse) to have plenty of content for many future Internet Disruption Report posts. I look forward to sharing my insights on these events with you in 2020 and beyond.

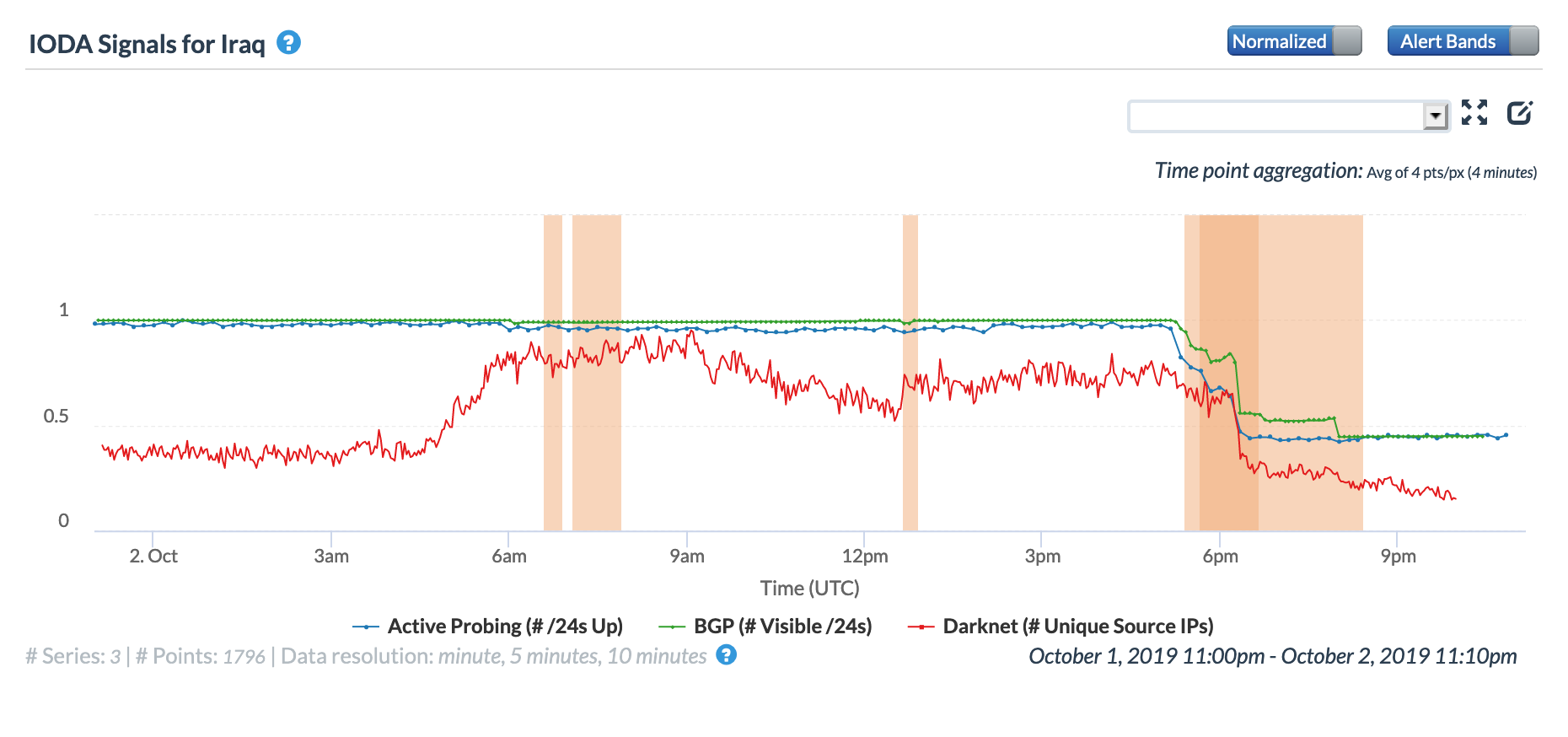

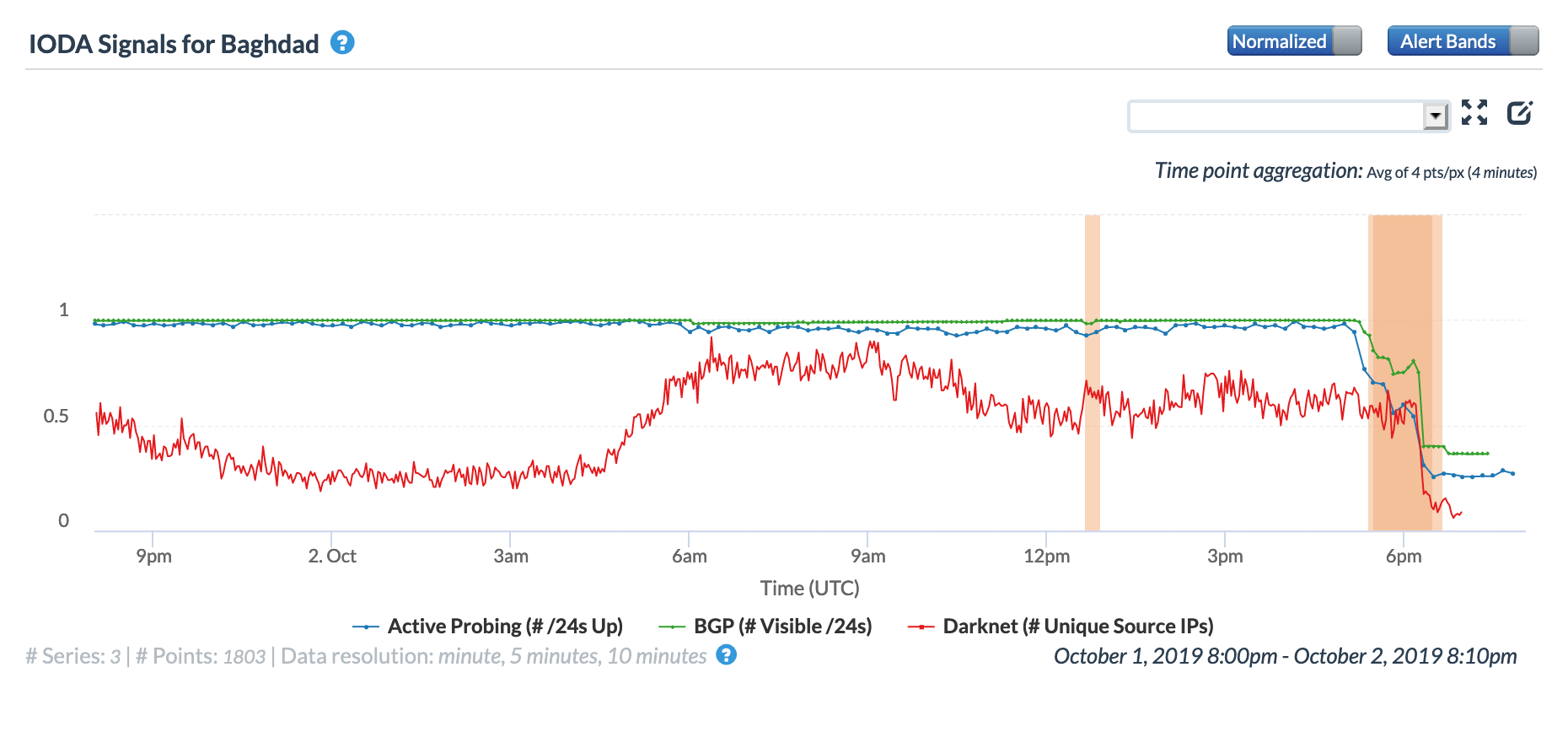

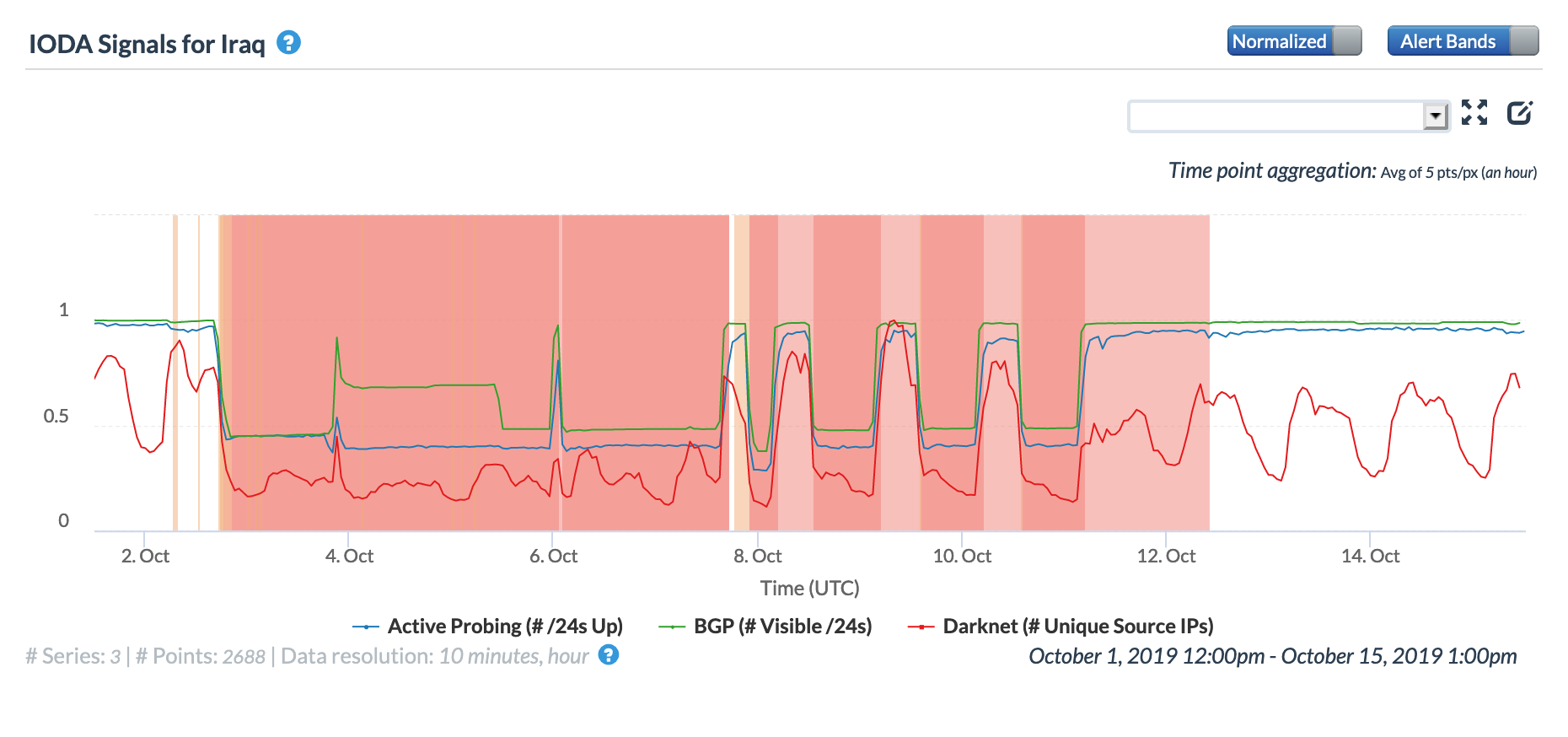

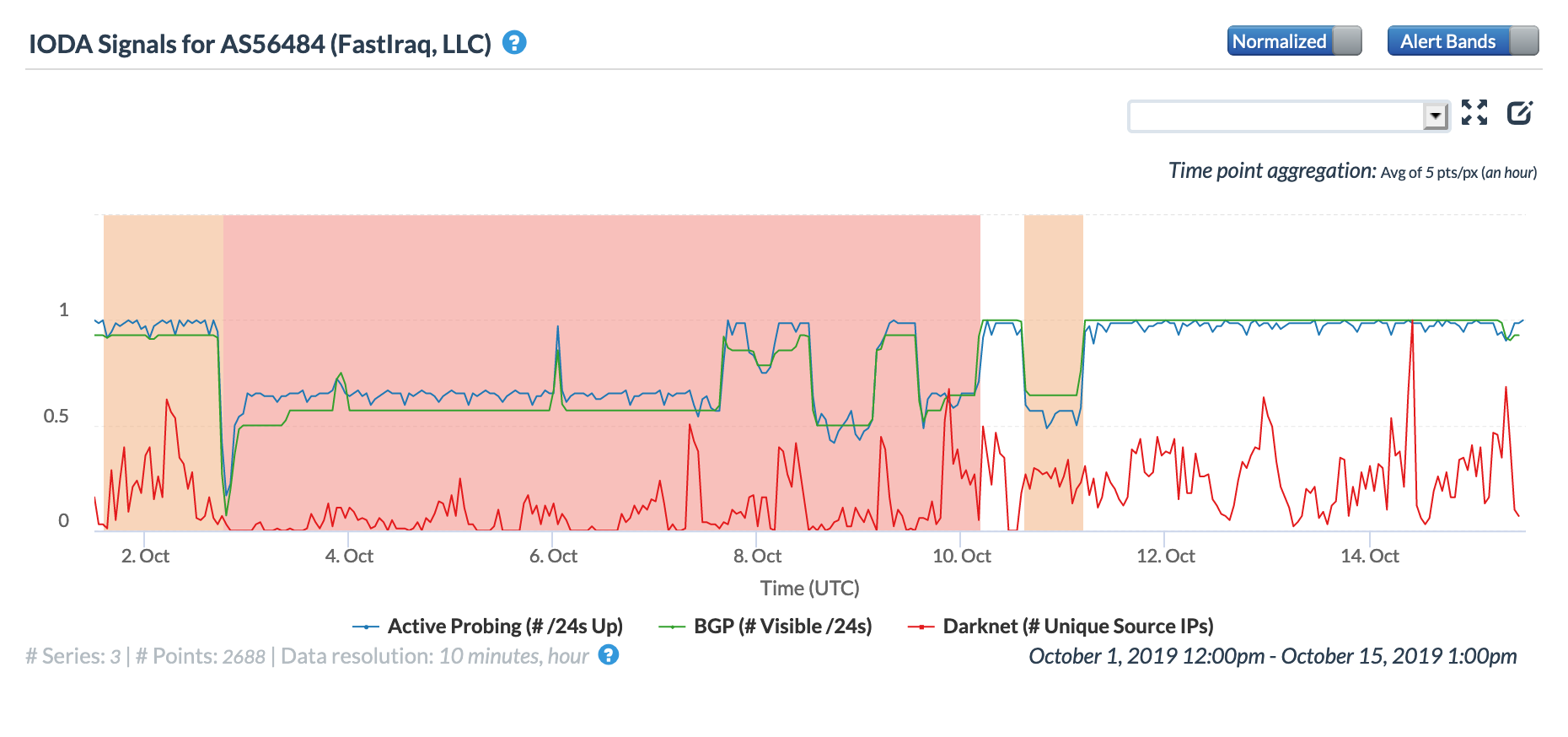

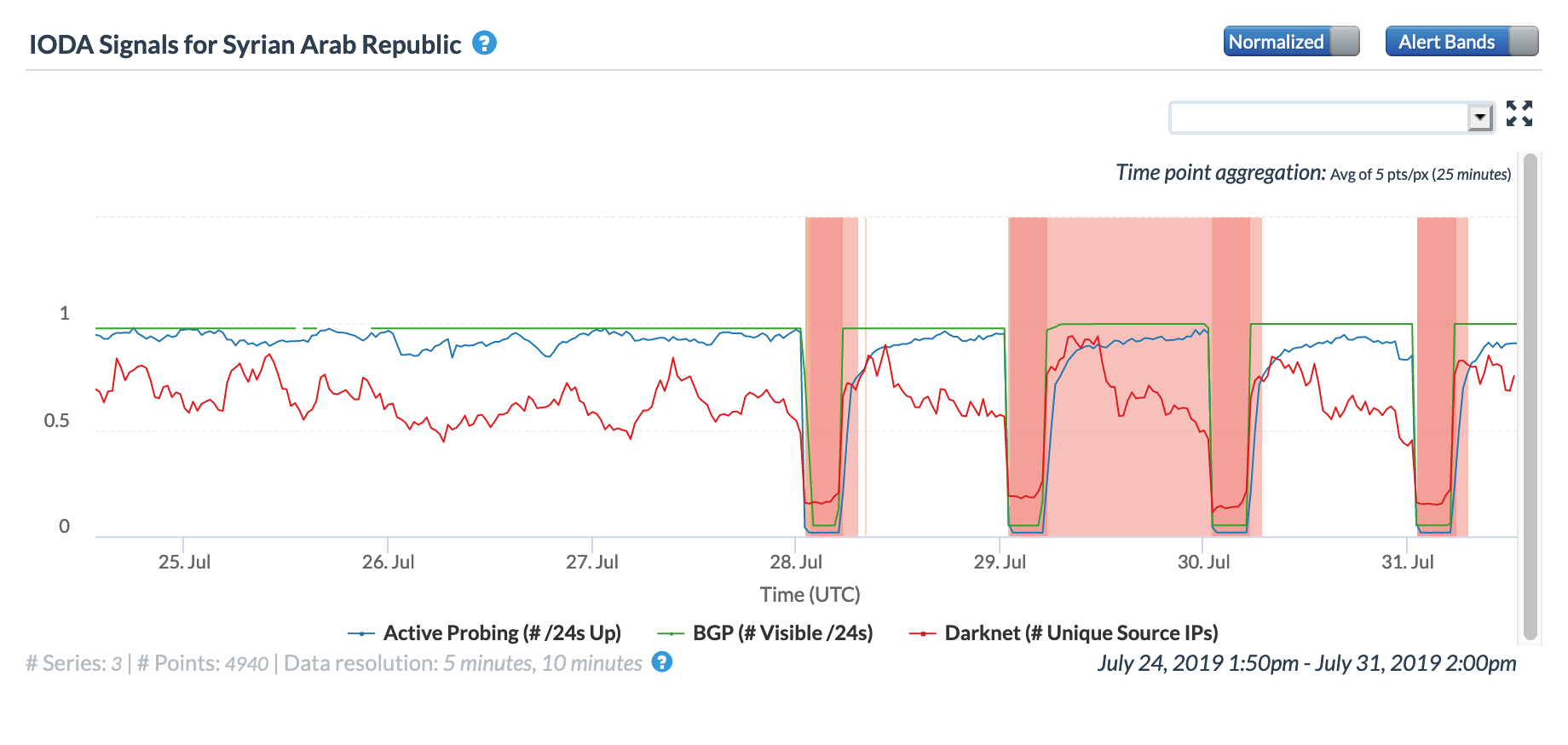

]]>Power Outages